The titanic feat of Enrico Mazzone, at work on the largest ever illustration of the Divine Comedy

When Dante Alighieri (Florence, 1265 - Ravenna, 1321) composed his Divine Comedy, Finland, we might say, practically did not exist. It was not an independent state, had no literary tradition (which would only begin in the 16th century with Michael Agricola) or even written records, and the Finnish language was just beginning to form at that time, in the 13th century. Interest in Dante and his masterpiece would only conquer Finland in the nineteenth century, when literati in the then Grand Duchy of Finland (a state that, at the time, depended on the Russian Empire) took to reading it and circulating it in academic circles, translating it in fragments, although the first complete translation would not be published until between 1912 and 1914, thanks to the work of the poet Eino Leino (Armas Einar Leopold Lönnbohm; Paltamo, 1878 Tuusula, 1926), who stayed for a long time in Italy to learn Italian as best he could and to be able to provide Finland with Dante’s work in Finnish, also accompanied by exegesis. Leino’s translation had a certain impact in Finland, was also commented on by Italian critics, continues to be read today, and made an important contribution to the knowledge of Dante among the Finns: other translations would later follow, and Finland has become a land very sensitive to the appeal of the Divine Comedy, known in these latitudes as Jumalainen näytelmä.

So much so that it is here in Finland that the largest ever illustration of the Divine Comedy is taking shape. Taking charge of the work is an Italian artist, Enrico Mazzone (Turin, 1982), who in 2016 moved to the small town of Rauma on the country’s southwest coast, not far from the ancient capital Turku, and from that date began his project: Illustrating the Divine Comedy on a mammoth 97-by-4-meter sheet of paper, an imposing 388-square-meter roll weighing nearly 240 kilograms, which will house the translation into images of Dante’s poem, made entirely in pencil with a dotted technique, reminiscent of an engraving.

Mazzone’s is a journey that starts from afar. A native of Turin, who grew up as an only child and was fond of drawing from an early age (his earliest memories run back to when he was five years old and scribbled his first sheets together with his maternal uncle, Angelo Sorrenti), he discovered the Divine Comedy as a child: the family owned, at home, an edition of the celebrated Comedy illustrated in 1861 by Gustave Doré (Strasbourg, 1832 - Paris, 1883), the great French painter and engraver who was the author of some of Dante’s images most familiar to the collective imagination. Dante and Virgil wandering through Hell wrapped in their heavy cloaks, Paolo and Francesca floating embraced amid the whirlwinds of the circle of the lustful, the bat-winged and long-tailed Geryon, Hell imagined as a harsh place made up of craggy cliffs, tangled forests, barren expanses: Gustave Doré’s romantic imagery, which makes Dante’s journey all the more epic, overwhelmingly invests Mazzone’s mind and fixes itself there without ever erasing itself. His path then continued after high school, at theAccademia Albertina in Turin, where the artist had the opportunity to study medieval bestiaries, late Renaissance iconographies, scholastic astrology, and where he read Panofski, Warburg, Saxl and the great art historians who studied the iconologies of past works and the ways in which images manifested themselves throughout the ages. Thus began a career that led him to develop the medium of drawing, on recurring themes: triumphs and carnivals, above all, with strong references to the art of the past.

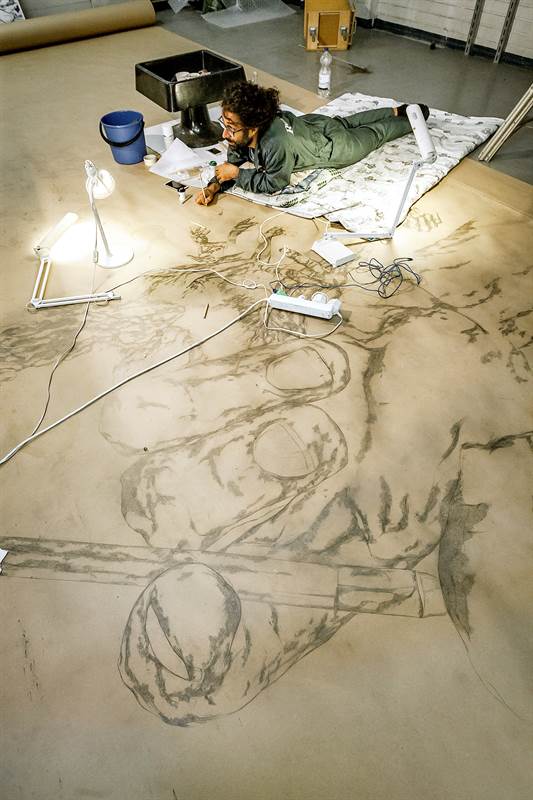

|

| Enrico Mazzone. Ph. Credit Simon Bergman |

His path then continues away from his hometown and away from Italy: Norway, Sweden, Germany, Denmark and Iceland are some of the countries where Enrico Mazzone spends his life, who since 2008, the year he left Italy, has been continuously traveling throughout northern Europe, even working as a cook to support himself, until he arrived in Finland in 2015. That year he settled for a few months in Rauma itself, where, for the Raumars artist residency directed by Hannele Kolsio, who invited him to the city, he was at work on another large-scale work, an illustration of the Kalevala, the epic poem by Elias Lönnrot (Sammatti, 1802 - 1884) based on the country’s traditional stories and representing the national epic of Finland. A work created in three months of extremely intense work, conducted in the strictest solitude and complete silence, and finally exhibited in the Ulvila Library of the Finnish city. After this work another relocation, this time to northern Greenland, to Upernavik, a village of just over a thousand inhabitants located on an island that can be reached only by internal flights from places further south, where in the hottest season, in July, temperatures barely exceed zero (and the climate is so harsh that trees cannot grow), but where the boreal sky can be admired in all its bright and shining wonder: so much so that in these lands Enrico Mazzone devoted himself, for two months, to the study of stars and auroras, aimed at depicting constellations on nautical maps found in the house museum that housed him during his Arctic sojourn.

The project of illustrating the Divine Com edy began upon his return from Greenland: Henry returned to Rauma where he continued to work as a painter and decorator and where, given the success of illustrating Kalevala, he proposed to do the same for the Divine Comedy. The inspiration, the artist himself recounts, came to him while jogging in a forest one day: the silent, tangled forest reminded him of the 13th canto ofHell, that of the forest of suicides, turned into bare, withered trees by divine retribution. “I wonder what these trees would tell if they could talk,” Henry tries to wonder, “I thought that, no more and no less, paper came to be precisely the cognitive, cerebral and emotional memory of the trees themselves. And having so much paper at my disposal, I allowed myself to try to note down what the forces and energies of the trees had to tell.” Finland’s forests, its stories: a repertoire of images and ideas that comes in handy in conceiving the Dante project. And the points of contact with the Northern European country’s saga are much closer than it might seem. "The denominator that unites the Comedy with the Kalevala,“ the artist argues, ”is an epic in poem format with strong national connotations. The Kalevala, like the Divine Comedy and like other epic structures, gives people a certain identity, a connotation, and it is still an initiatory path, just like the Divine Comedy. That’s why I experienced this work from the very beginning with a remarkable filter of suggestions, because when I started to work on the illustration of the Dante poem I literally let myself go, Stanislavsky-style, I identified myself not necessarily with a figure who has to bring or bring back a certain telluric energy, but nevertheless with someone who has to begin an initiatory path: I was literally lost in the beginning because I didn’t know how long I was going to be here, I had to adapt to the weather conditions, I often had to improvise the schedule, travel all the time, recalibrate the work, deal with emotional surges."

Paper, the huge and eerie thicket, Dantean memories: “without filtering some,” the artist continues, “I began my slow and inexorable climb, with endurance and dedication.” Enrico thus tries to expose his idea. The proposal is immediately accepted: a paper mill in Rauma, UPM, gives him the huge sheet, and Rauma’s councillor for culture, Risto Kupari, the local Lions Club and a supermarket, Prisma, provide him with the material and the studio in which to work.

|

| Enrico Mazzone at work on his Divine Comedy |

|

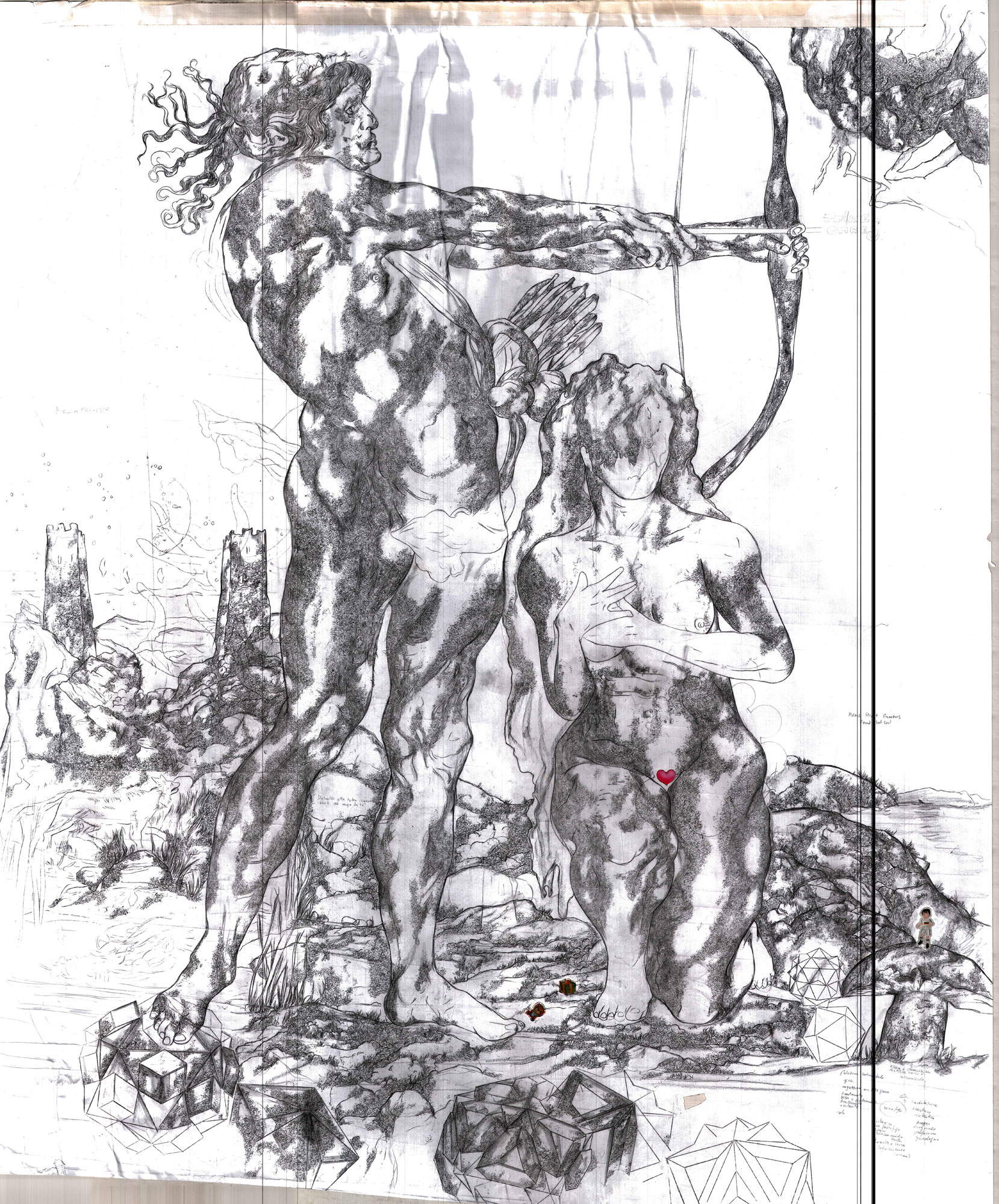

| Enrico Mazzone’s Kalevala |

The work can thus begin. First with preparatory drawings, then on the sheet that will accommodate the finished work. It is extremely tiring work: the first year spends between ten- to fourteen-hour long work days, with breaks on weekends. The work must be divided into days, as painters do when they paint frescoes. Enrico Mazzone’s undertaking, after all, harkens back to ancient experiences, evokes the artist’s challenge to his physical limits, calls to mind the Vasarian image of the artist who “toils” in art and engages in a challenge to nature. A work that engages him almost to the point of exhaustion, that undermines his health (months spent lying on sheets, almost always in uncomfortable positions, convert to sciatalgia), that results in “physical and emotional hardship” from having to work and live alone, that leads him to change three different studios in four years. In the meantime, other supporters join the venture: Enrico is supported by the Institute of Italian Culture in Helsinki and Marco Miccoli, creator of the Dante Plus project, as part of which they are considering bringing the design, which will be finished in 2021, to Ravenna for the celebrations of the seven hundredth anniversary of the poet’s death.

The work is structured as a long continuous narrative, and the choice of format to give the illustration was not among the easiest. “There are two sequence plans, to use a videographic term,” says the artist, "since ’summarizing’ the Comedy in a chronological-linear space was very complicated, because a ’faithful’ illustration of the poem that unfolds continuously should have a geography that verges more on the vertical, as it is more capable of rendering Dante’s universe. At first I thought of reproducing the Commedia based solely on Dante’s cartography, respecting the various cantica, Inferno, Purgatorio and Paradiso, in a more precise way." But a vertical sheet would have entailed enormous technical difficulties. “It would have been utopian, I would have found it impossible to expose the sheet if I had decided to unfold it vertically,” Enrico Mazzone continues. "And since I had to unfold the sheet horizontally, I thought of using a single sequence with close-ups and close-ups and backgrounds: I was reminded of the stylistic work of Leonardo da Vinci, who in landscapes manages to have a remarkable detachment, which allows the figures in the foreground to stand out but without lacking the precision of the details of the background itself. So I have tried to do my best in the meantime to render in images what everyone should perceive, and then to create a certain harmony and continuity. A continuity that, moreover, I would not mind evoking through a cyclorama, arching the drawing according to an oval or circular pattern: this could allow observers not only to see the work statically, but also to walk inside the work."

Ravenna, the last land to know Dante’s genius when the poet was alive, could be the city where Enrico Mazzone’s undertaking will see its conclusion: at the moment, the artist has drawn 66 of the 97 meters of the sheet. Paradise is missing. And now the artist and his entourage are working to work out the details of the sheet’s transfer to Italy: a special container has been made that can enable the transfer from Finland to Ravenna, and the city of Rauma has already provided Enrico with the pencils needed to bring the work to its conclusion. An inspection was also made in Faenza, at the church of Santa Maria dell’Angelo, a place that could accommodate Enrico Mazzone’s great Divine Comedy. Indeed, inside the house of worship it is possible to set up a structure that will not be a cyclorama as the artist would like, but that will still give visitors the possibility of “embracing” the work according to Enrico’s intentions, and that will not impede the reading of the spaces of the church, which has fifteen-meter-high walls (four of which would be occupied by the sheet).

|

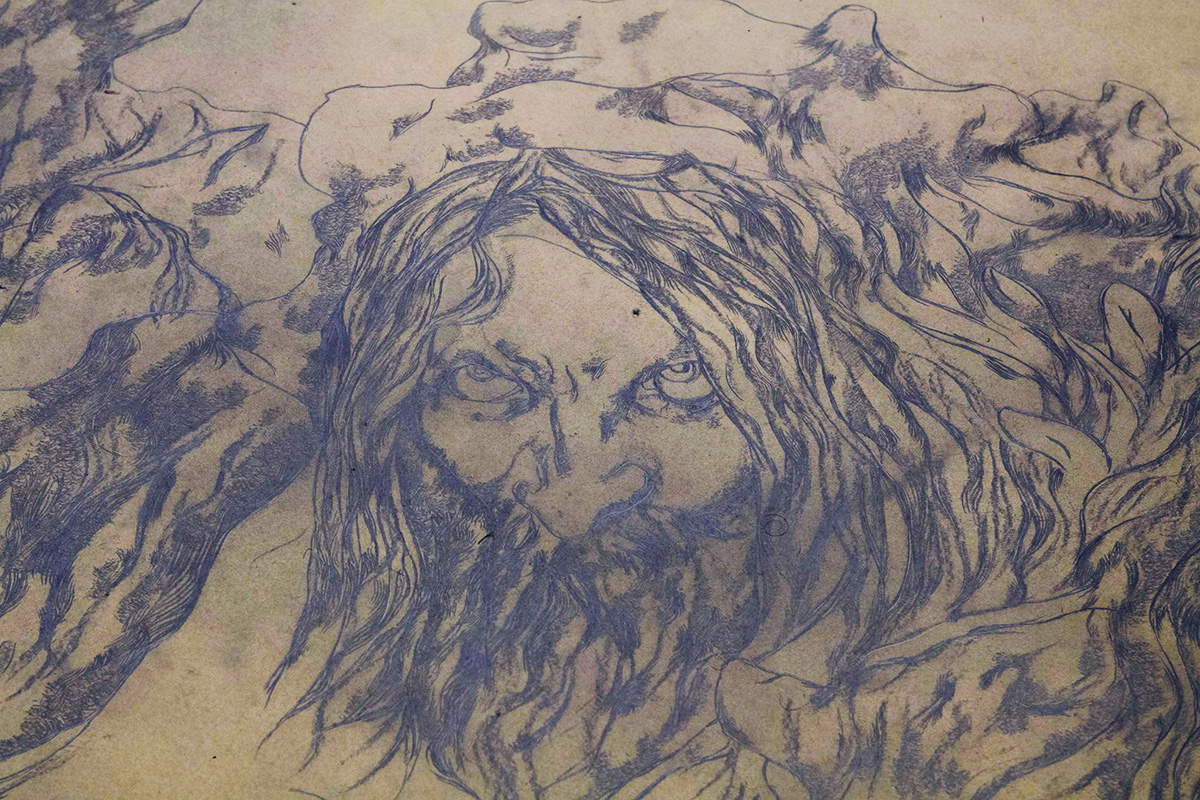

| Enrico Mazzone, Divine Comedy (2016-2020), draft for the figure of Virgil |

|

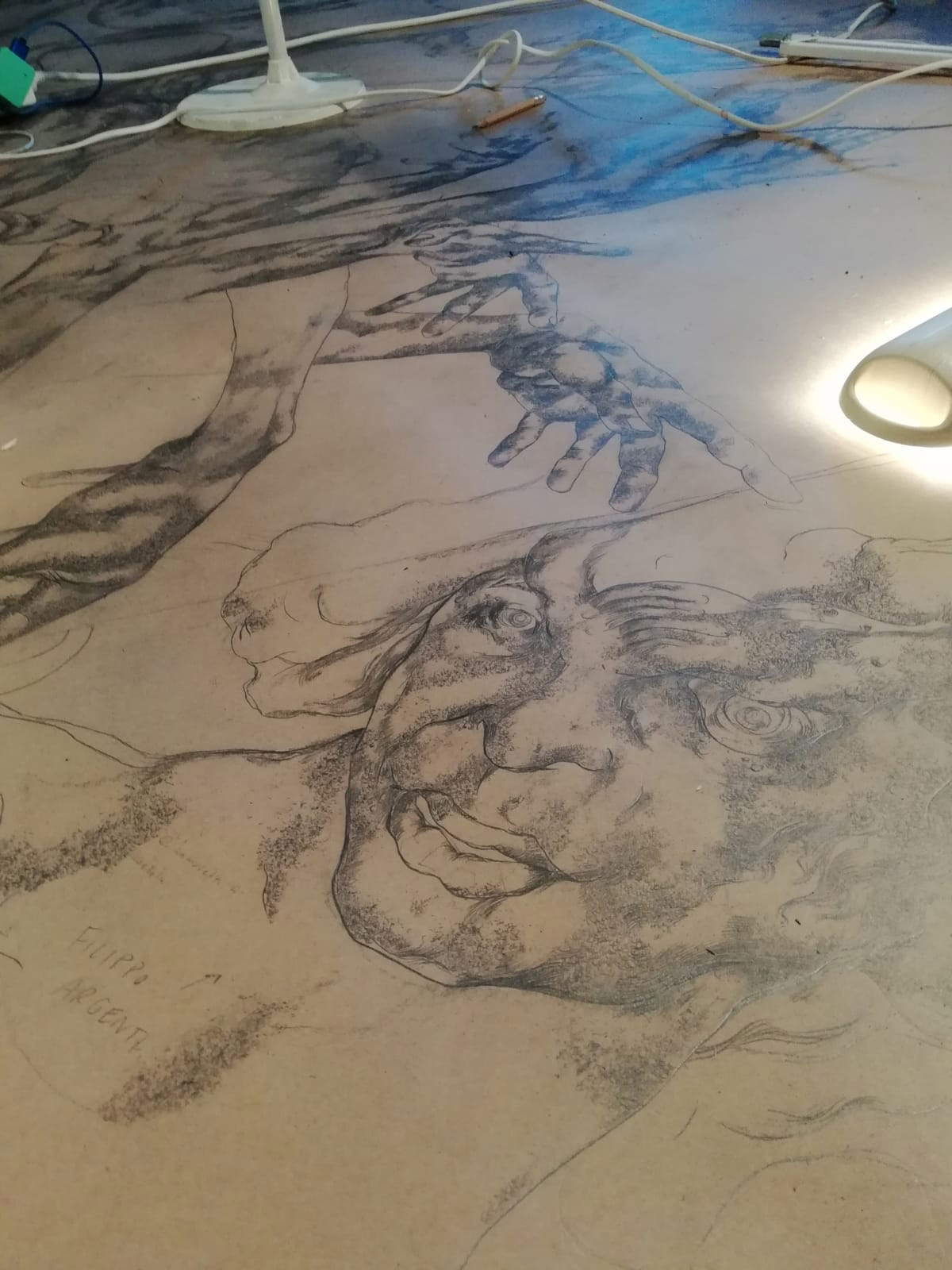

| Enrico Mazzone, Divine Comedy (2016-2020), Geryon |

|

| Enrico Mazzone, Divine Comedy (2016-2020), Filippo Argenti |

Work on the Paradiso will begin in June and will likely end in December. So, after illustrations by the great artists of the past and present (from Sandro Botticelli to Gustave Doré, from William Blake to Robert Rauschenberg, from Adolfo De Carolis to Francesco Scaramuzza, from Mimmo Paladino to Brigitte Brand), a new Divine Comedy in pictures is set to join the long list. Enrico Mazzone’s point of reference, however, remains Gustave Doré: not only the one of the Divine Comedy, but also the Doré illustrator ofOrlando furioso, another work imprinted in the figurative imagination of the Turin-based illustrator. Doré, according to him, "perfectly embodies the spirit of the Comedy. So many of us have grown encyclopedic thanks in part to his images, which are strong and elicit emotional responses." But on a technical level, another artist is the one Henry draws inspiration from: Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528). When he was studying at the Albertina, the artist was unable to take an engraving course. However, he was always fascinated by the medium and tried to arrive at a graphic practice that could imitate it. “This work,” he tells us, “is for me an arrival at a new technical and practical knowledge of the work: dotting on this immense sheet until it almost loses its connotation. The proportions were made to scale from preparatory drawings I made earlier, and then I proceeded with the squaring, trying to keep myself as close as possible to a truthful form of the figures and landscapes, without going so far as to be hyperrealist because I am not capable of it and it is not my stylistic signature. Dürer certainly influenced me: with his works he maintains a very symbolic, almost hermetic iconographic aspect, which marked me deeply. And I tried to direct myself toward what the engraving could not give me, trying to emulate it as much as possible.”

No one has so far seen Enrico Mazzone’s work in its entirety. The paper was conceived as a huge papyrus, rolling up and unrolling as needed. So far, it has never been opened in its entirety. And if Ravenna can seize the opportunity, it will be she who will be the first to see Enrico Mazzone’s Divine Comedy in its entirety, it will be she who will allow the public to retrace Dante’s poem with Enrico Mazzone’s images, it will be she who will give substance to this dream and become the final stage of the artist’s titanic undertaking. Exactly seven hundred years after the passing of the great father of our literature.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.