by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 15/04/2018

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

Simone Pellegrini proposes a timeless art made of ancestral visions populated by intertwining human bodies, phytomorphic beings, primordial organisms, strange codes. A profile of his art.

Many of those who have written about Simone Pellegrini (Ancona, 1972) could not help but quote Aby Warburg. Just as the great German art historian had created his Mnemosyne atlas to construct his maps of figurative memory, in the same way the Marche artist gives life to maps of symbols that seem to perpetuate in the contemporary riddles of ancestral symbols that compose bizarre visions populated by strange phytomorphic creatures, single-celled organisms, men and women who fuse their bodies in fertile amplexes, objects that transform and take on a new nature. And without any precise references to epochs or places. Simone Pellegrini’s maps could come from an undefined antiquity: the journey even starts from the cave paintings of prehistory (think of those of Altamira) and then goes into the history of medieval art, from the intertwining reliefs of ancient Romanesque cathedrals to the whimsical alphabets of Giovannino de’ Grassi, but it goes further, to explore remote civilizations, crossing the East of Siyah Qalem and reaching the extreme West of Mayan sculpture.

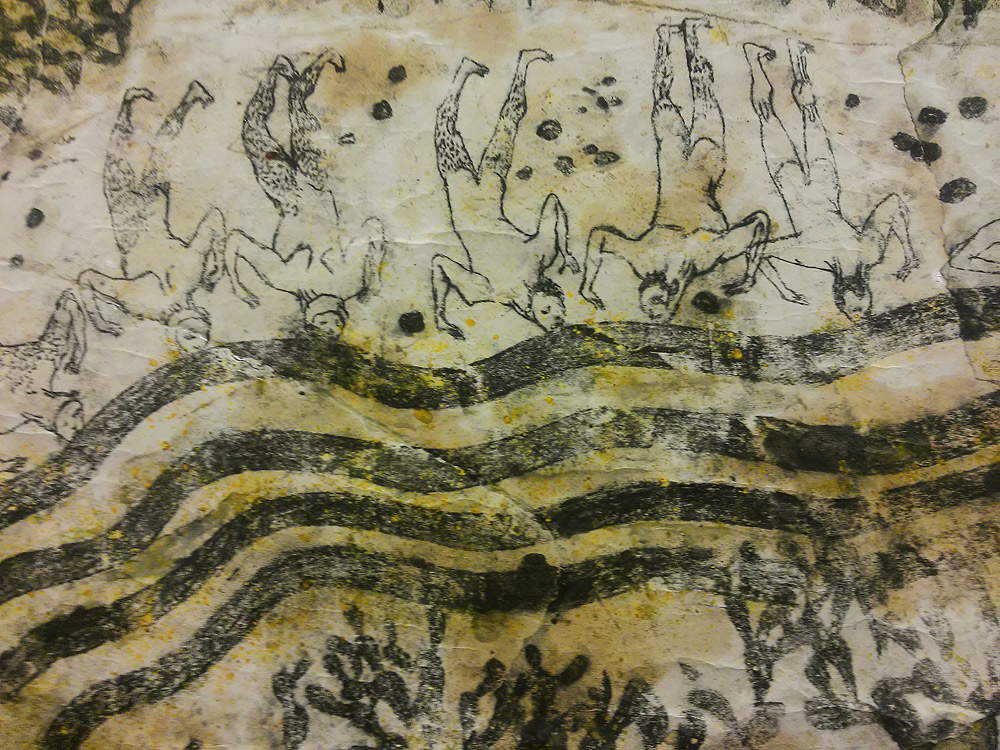

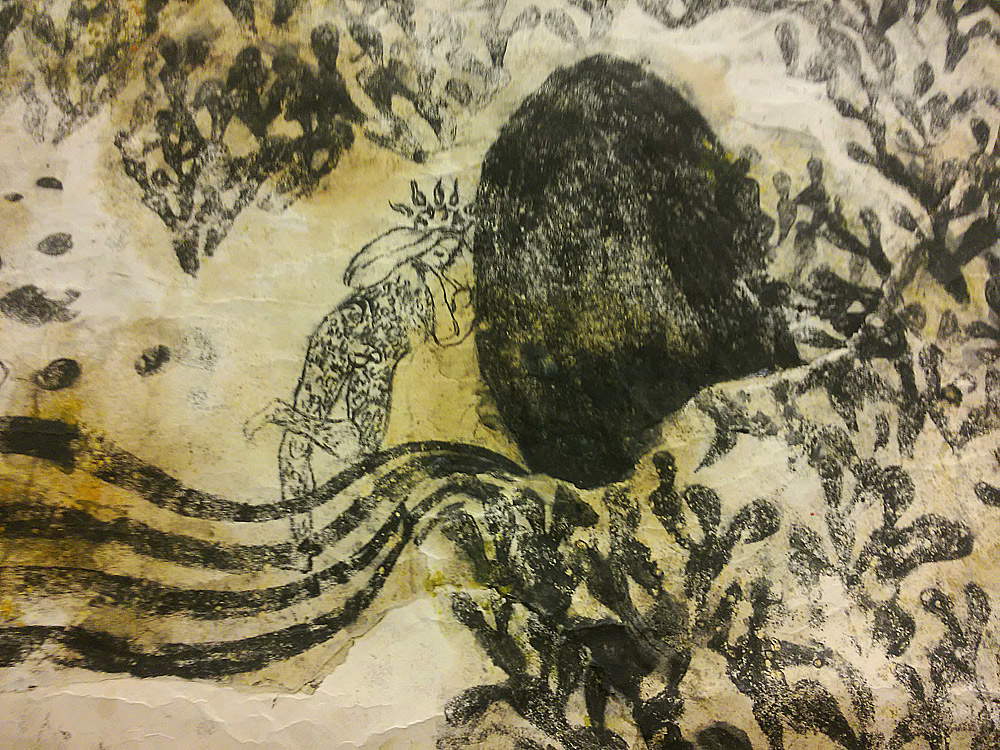

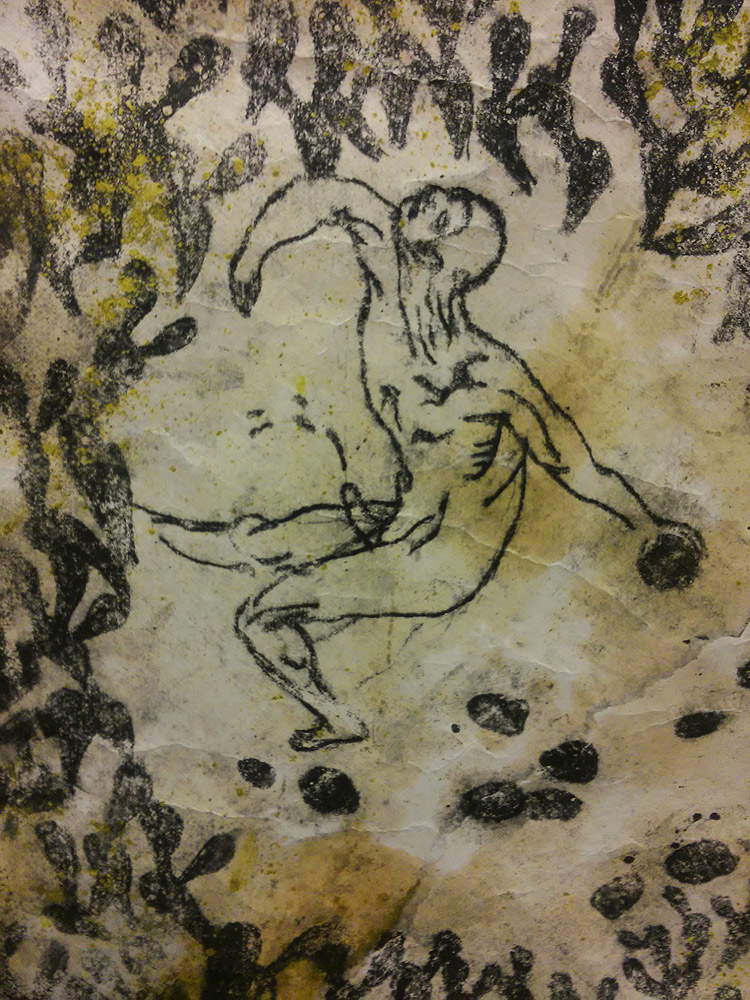

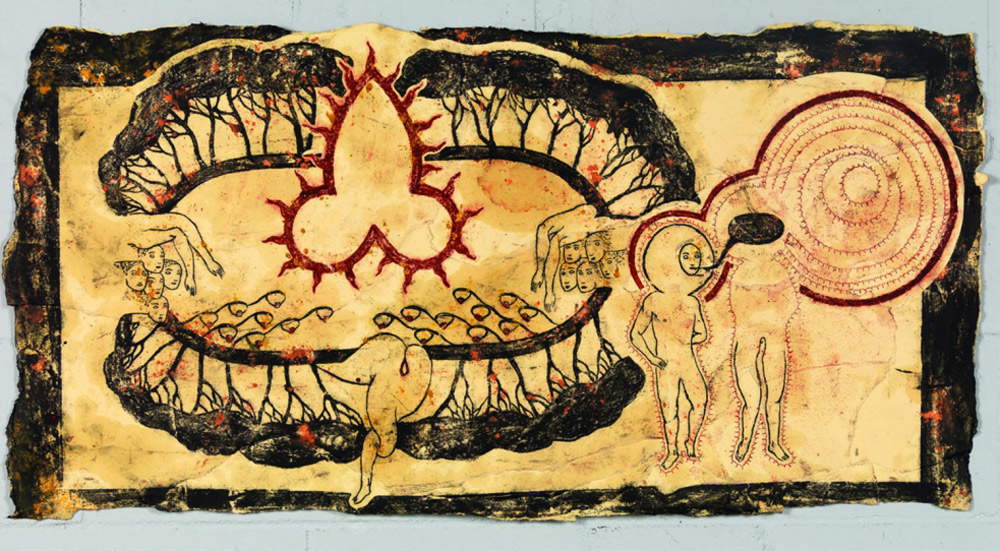

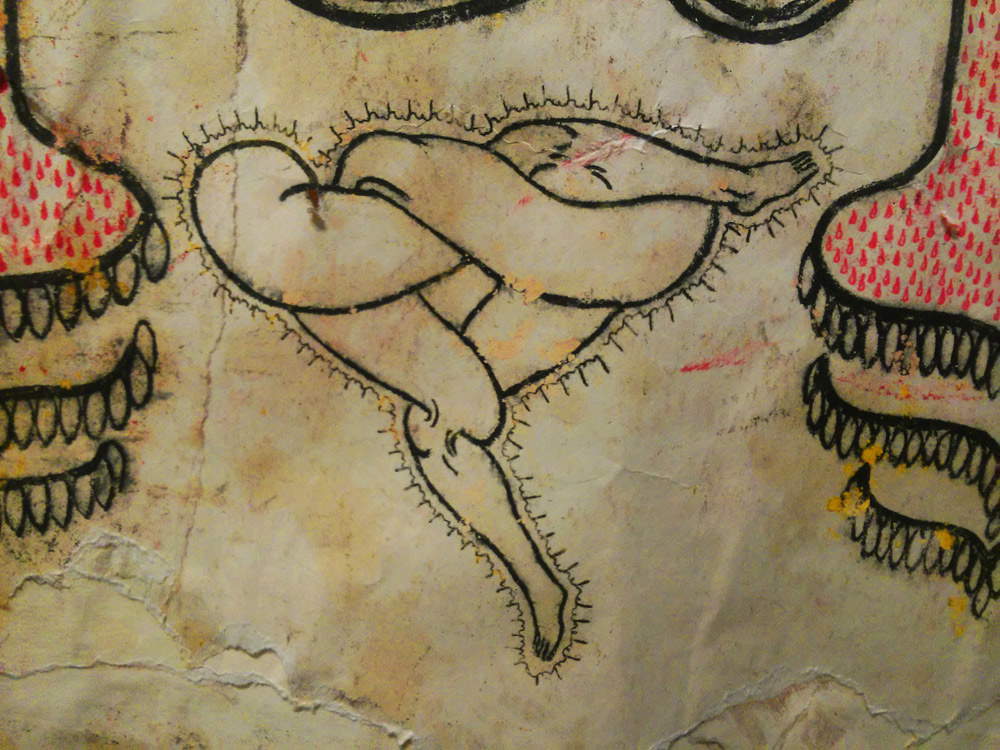

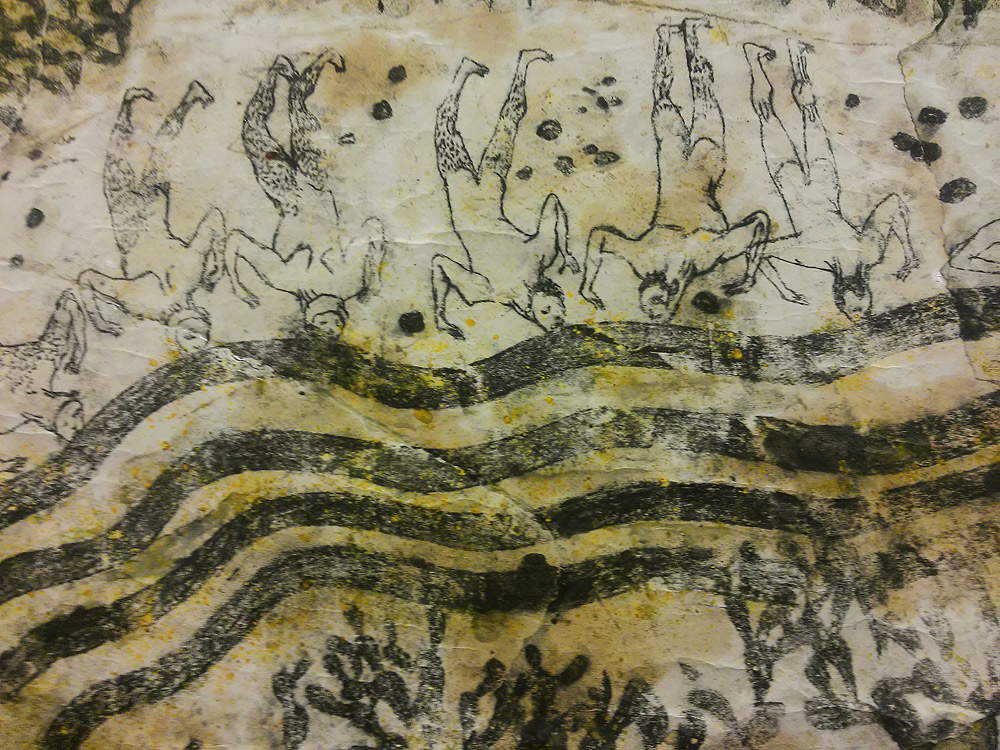

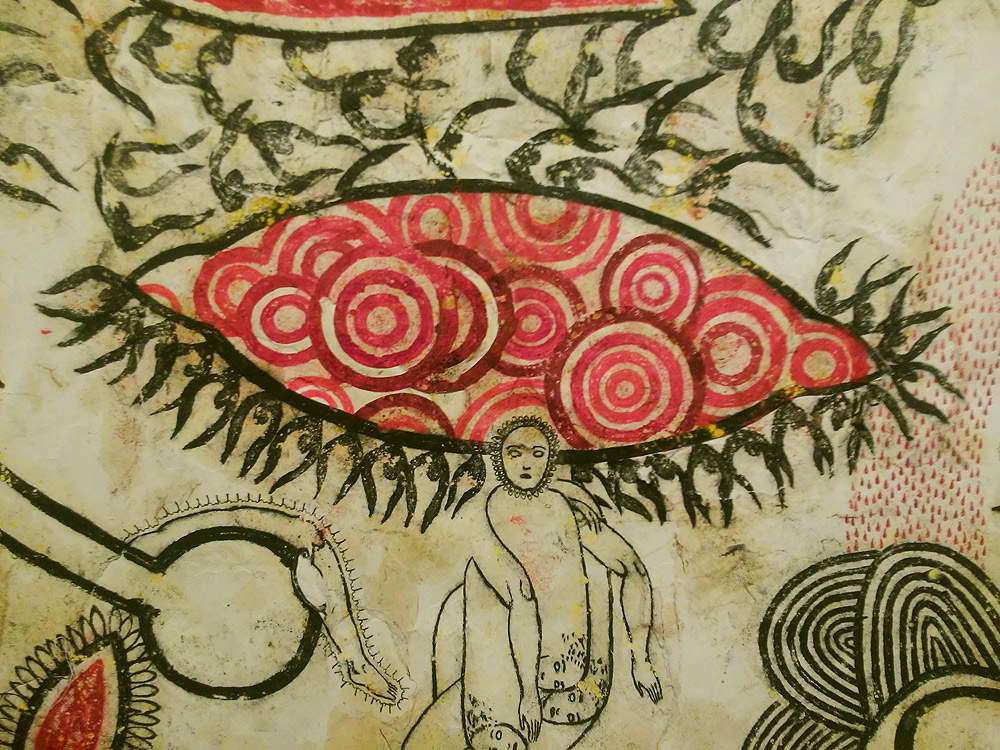

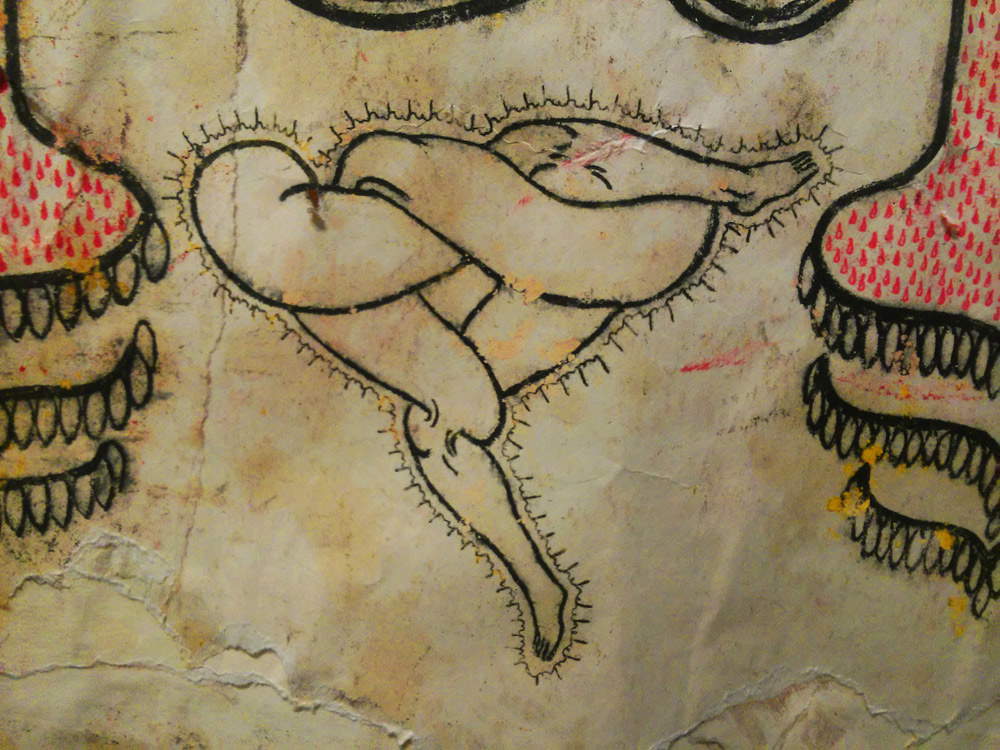

The process by which Pellegrini’s works are created also has ancient origins: his maps use a technique close to that of the monotype, the invention of which is sought to be traced back to the great Giovanni Benedetto Castiglione, known as Grechetto, one of the most important artists of 17th-century Genoa. The artist created individual fragmented images, his special monotypes, and after oiling and then drying them, he imprinted them on paper, then destroyed the matrices, the originals. Almost the technical transposition of the obvious tendency to overcome individuality in an attempt to trace a history of culture and a history of the world. For the same reason, i.e., to transcend the individual, the bodies almost never appear in their entirety: they are broken down and dismembered, almost as if they were veterans of Dionysian rituals where the individual was sacrificed in the name of the god. And the whole appears cloaked in a language that Simone Pellegrini himself defines as baroque: “because it is continually sossimorous, it denies itself to the fold,” he pointed out in one of his writings.

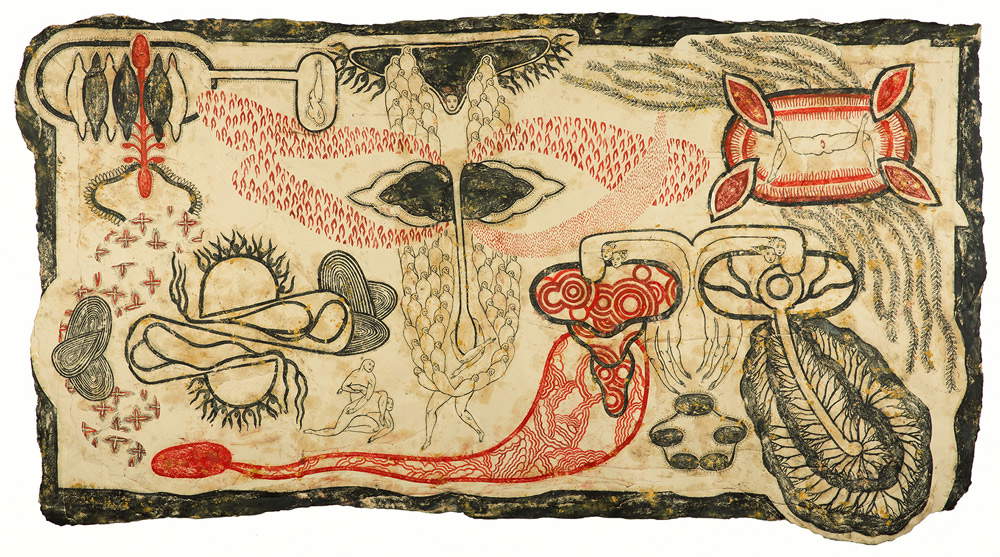

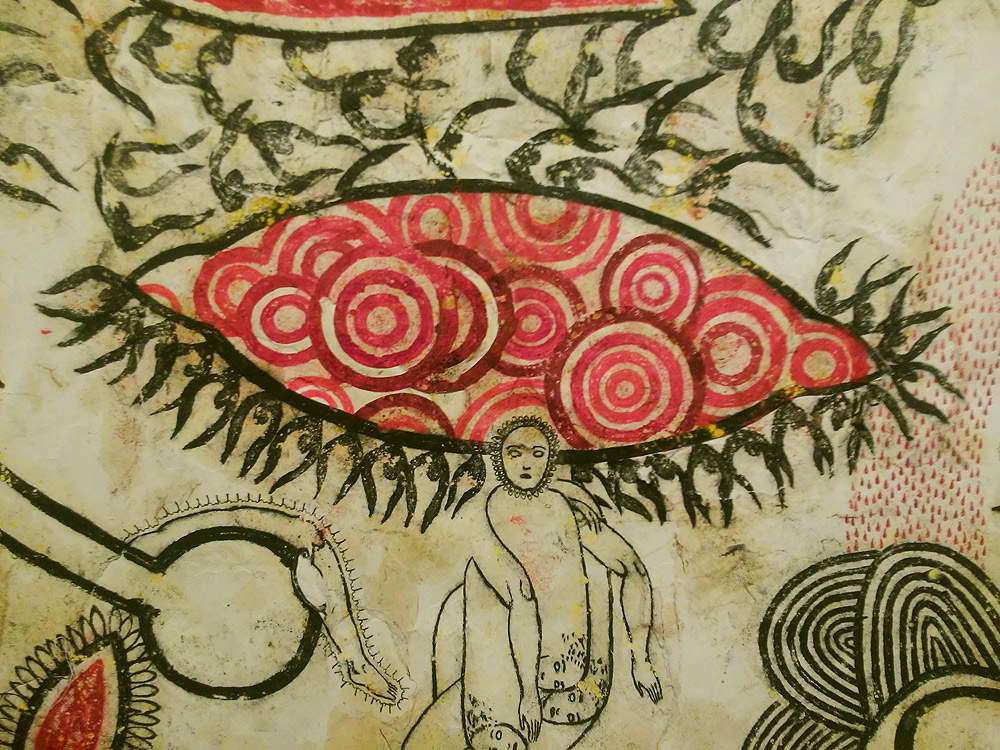

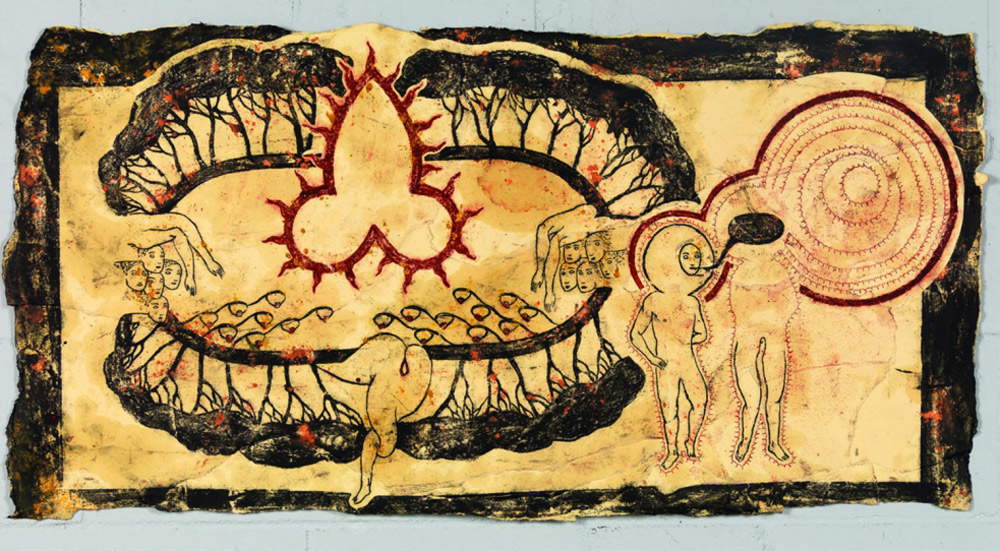

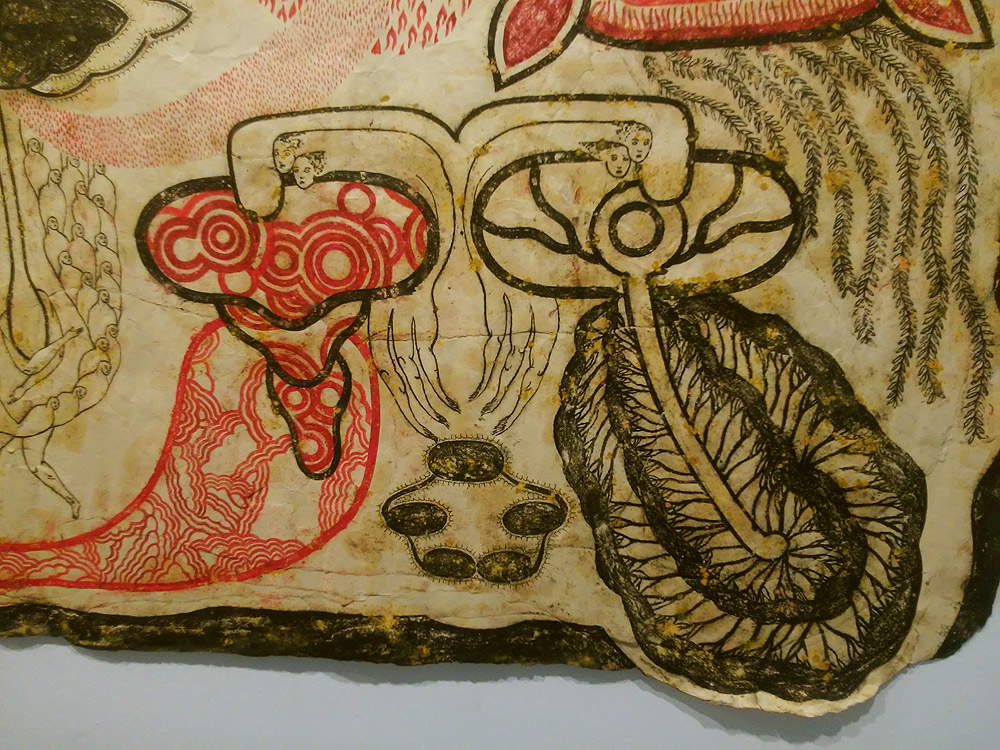

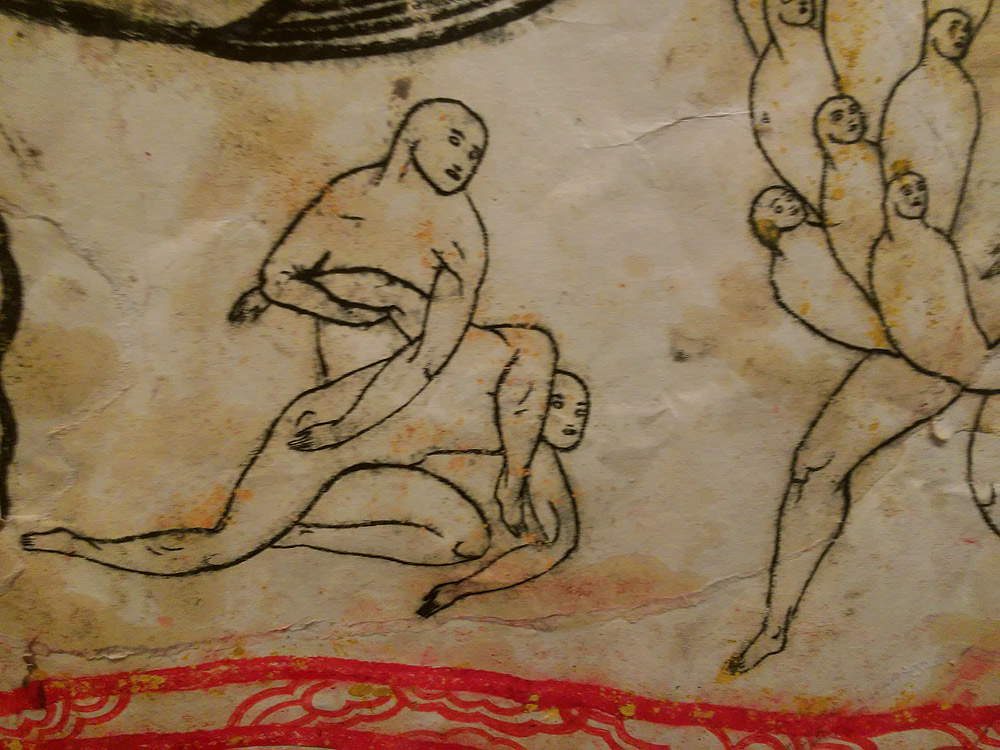

Similar tensions have always been present in Simone Pellegrini’s work. The example of a 2005 work, L’ordo degli incomparabili, where the composition, traced on a yellowed, burned and slabbed paper (the typical support of the artist’s works, almost a parchment not spared by the action of time) transports us inside a dense forest in which we observe a woman in which a fluid flows from her genitals, a sap, which swells as she proceeds through the forest, attracts some men who lie down to drink from it, and then gets lost in the dark entrance to a cave that ends her journey. Almost a metaphor for the cycle of life, which could, however, also be safely read in the opposite sense, with the fluid emanating from some deity inhabiting the cavern and flowing down to fertilize the woman. This poetics of the ambiguous is typical of Simone Pellegrini’s production. Just as typical are some recurring symbols: floating cells, leg entanglements, phallic symbols, female genitalia, seeds and membranes. In Conversazione azimutale (Azimuthal Conversation), for example, two characters with elusive features (one of them even lacks an upper body: again, characters without individual connotation) talk at the edge of a forest with trees arranged in a circle. Trees that are almost reminiscent of the thirteenth-century miniatures of Hildegard of Bingen, where plants sprouting from a circle symbolized the passage of time and seasons, but the underlying ambiguity of Pellegrini’s figuration makes these strange pines appear to us almost as fluids converging toward the central ring...or vice versa. In the midst of these elements, a huge phallus stands out, toward which men and women tend and which celebrates the sacredness of union. “The whole scenario,” Simone Pellegrini pointed out about the recurring symbols in his works, “is arranged to accommodate the event [...]. In the representation the elements are determined that want to induce the representative himself to the revelation-remembrance of that which, far from expropriating him, relocates him. Here the apotropaic. Here the anticipatory representation, representation as delimitation of the epiphanic place in which the arrangement of elements becomes a pretextual formula for the appearance of the actor. To circumscribe the space of temporal precipitation, in which the sign emergence is immediately given as an apòcryphal text. To look then, as we look at what does not belong to us. With desire.”

|

| Simone Pellegrini, L’ordo degli incomparabili (2005; mixed media on paper, 200 x 310 cm) |

|

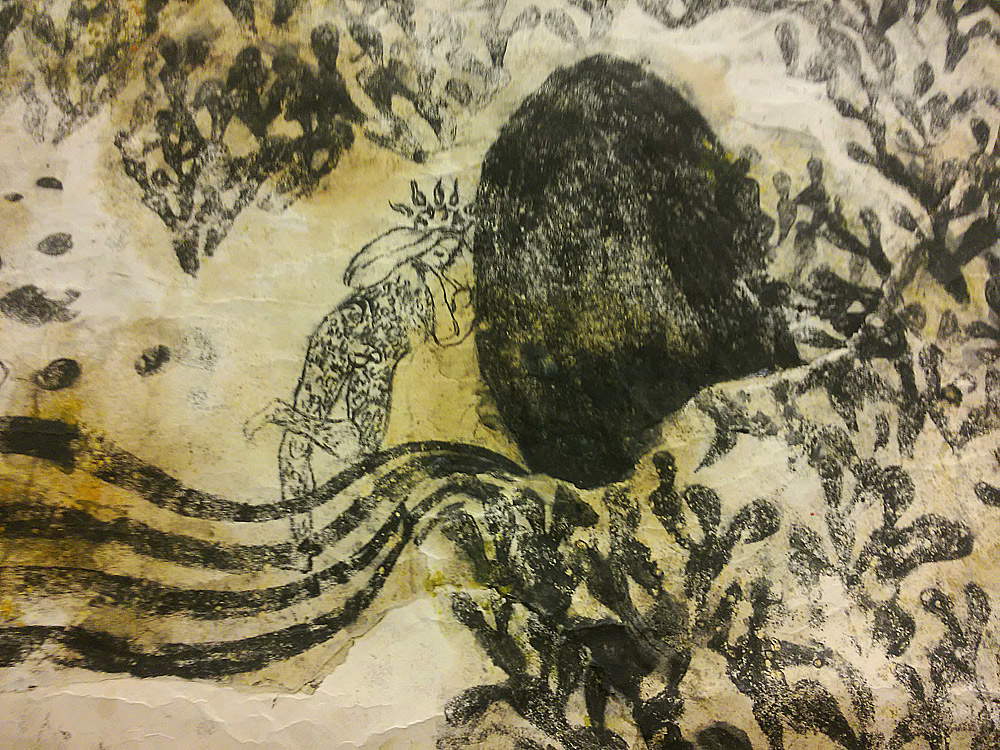

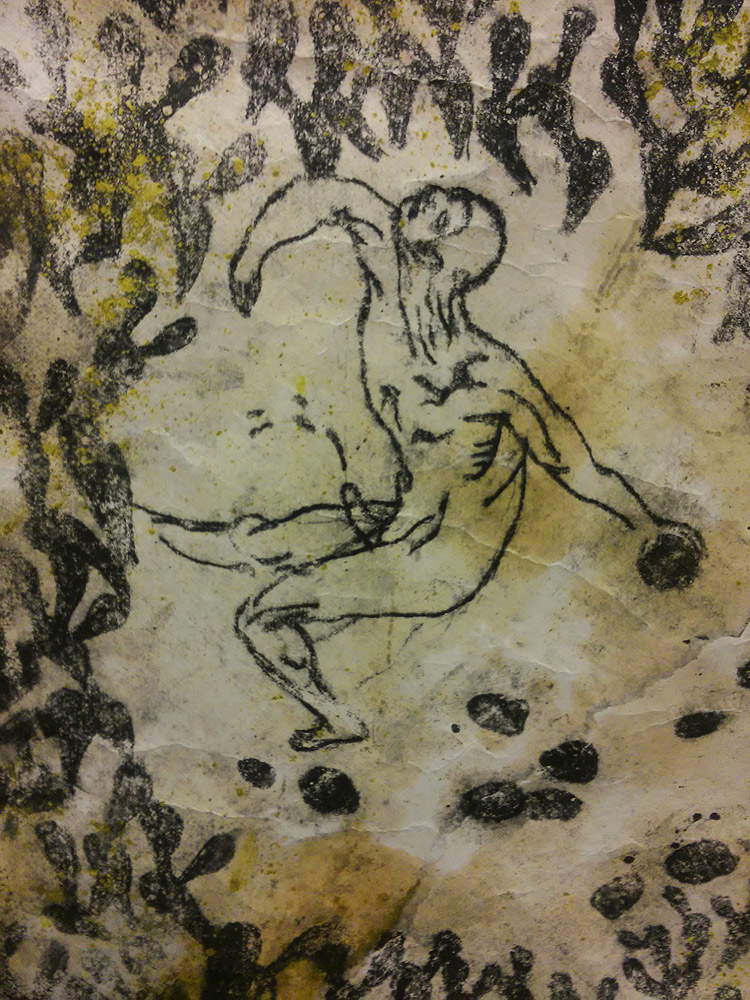

| Simone Pellegrini, The ordo of the incomparables, detail |

|

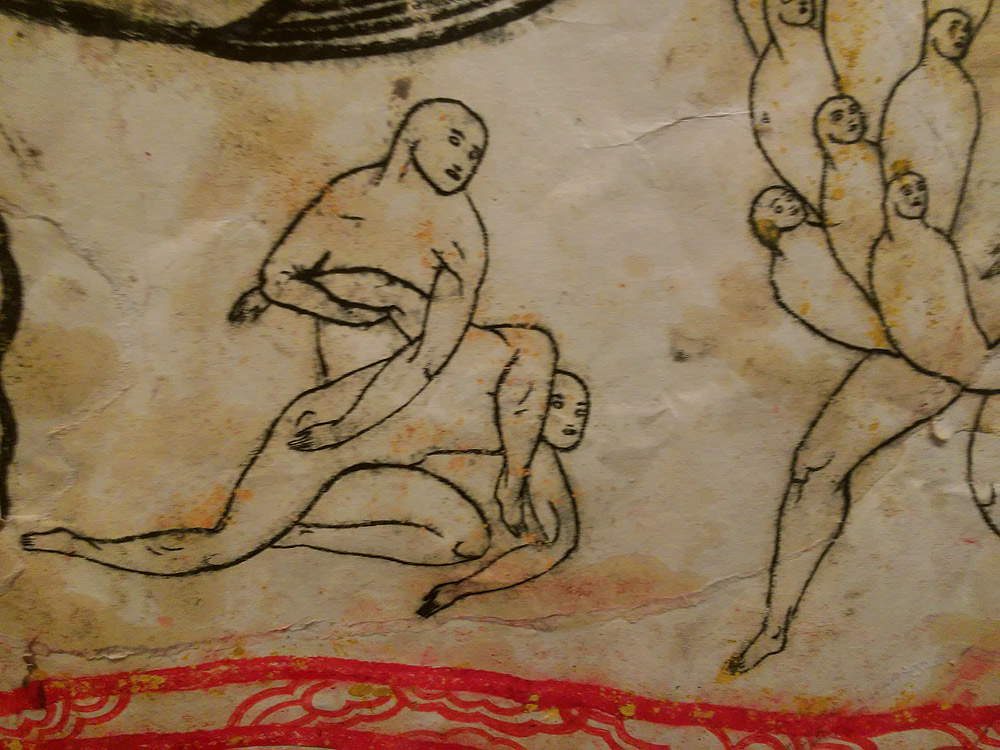

| Simone Pellegrini, The ordo of the incomparables, detail |

|

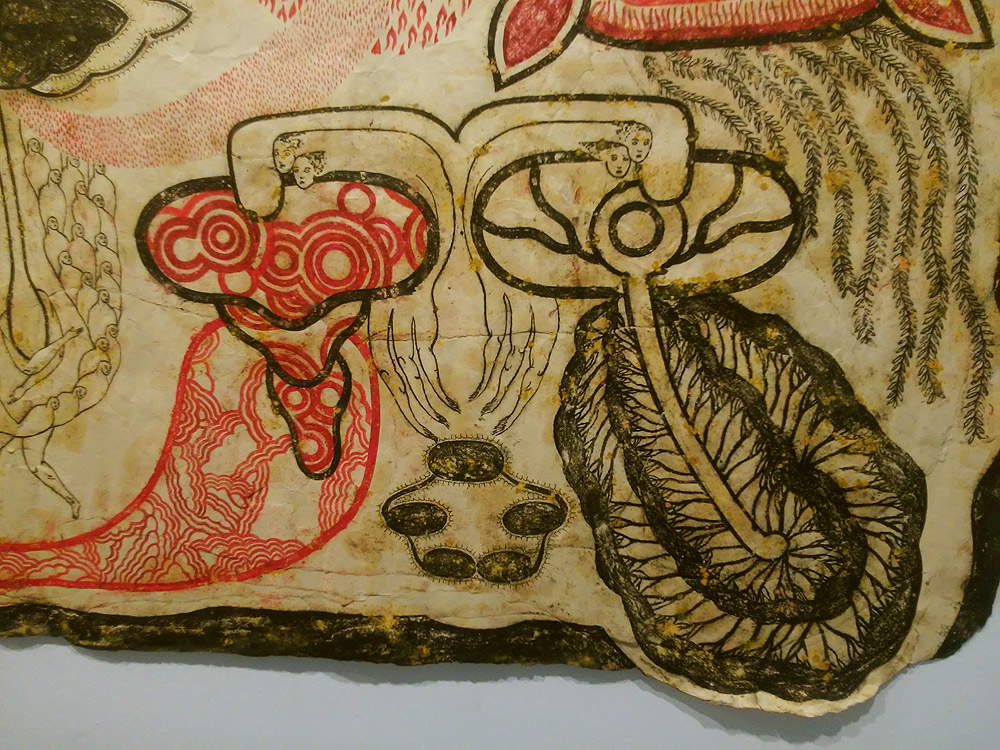

| Simone Pellegrini, The ordo of the incomparables, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, The ordo of the incomparables, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Azimuth Conversation (2010; mixed media on paper, 55 x 108 cm) |

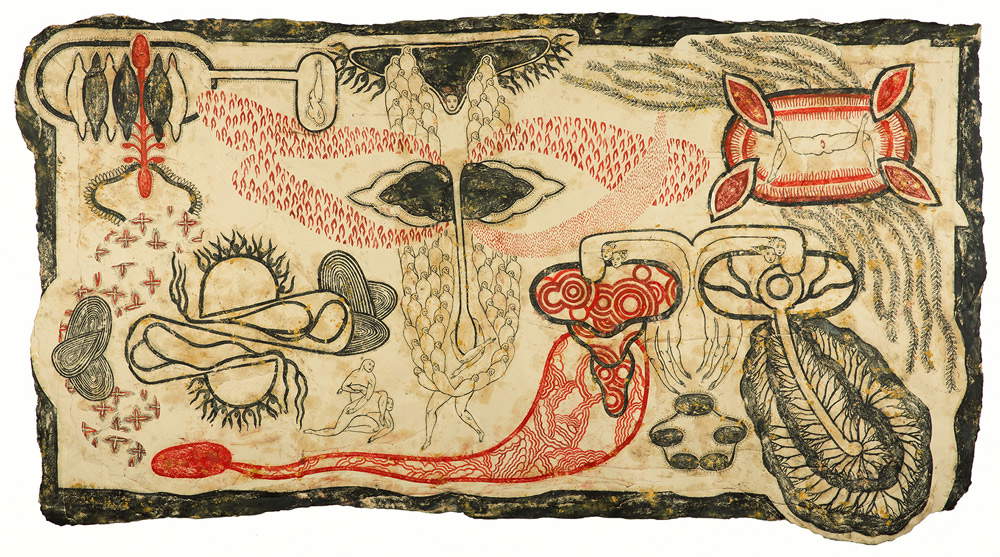

This convulsive theory of symbols can also be found in more recent works, such as Andante causato, where we see almonds that appear to be taken from medieval miniature (but which, instead of the deity, contain portions of the human body, arms intertwining women’s thighs spread wide in quivering anticipation, the latter similar to those that populate Carol Rama’s works), primordial organisms floating amidst flames, vegetation and assorted germinations, elements replicating themselves, small torments of women and men multiplying. The work, from 2017, is on display at Simone Pellegrini’s latest solo exhibition, Ostrakon, held from March 24 to May 5, 2018 in the spaces of the Cardelli and Fontana gallery in Sarzana, with which the artist has been collaborating for several years and which has hosted several of his exhibitions. Ostrakon was the shard of earthenware on which, in ancient Greece, the names of citizens who were to be exiled were written. Similarly, the fragments that make up Simone Pellegrini’s scenes convey messages, content. Pietrò Gagliano specifies that “as in the presence of any code, the question arises as to which spheres it allows access to, which worlds it connects and in what way this code, made penetrable, decoded, can be used.” One possible answer, among many, can therefore be identified “in the construct of form, that is, in what we can define as the continuous dissolution of the artist’s idea in figuration: a horizon that contains licona, in its original meaning of image, and places it in the network of cultural and emotional ties present to the author and intentionally introduced by him in the work (or sometimes, as will be seen, emerged almost autonomously, by virtue of a proper and hidden branching vitality with which the images are provided).” Ostrakon, then, also as the “exile” of the idea on the material support.

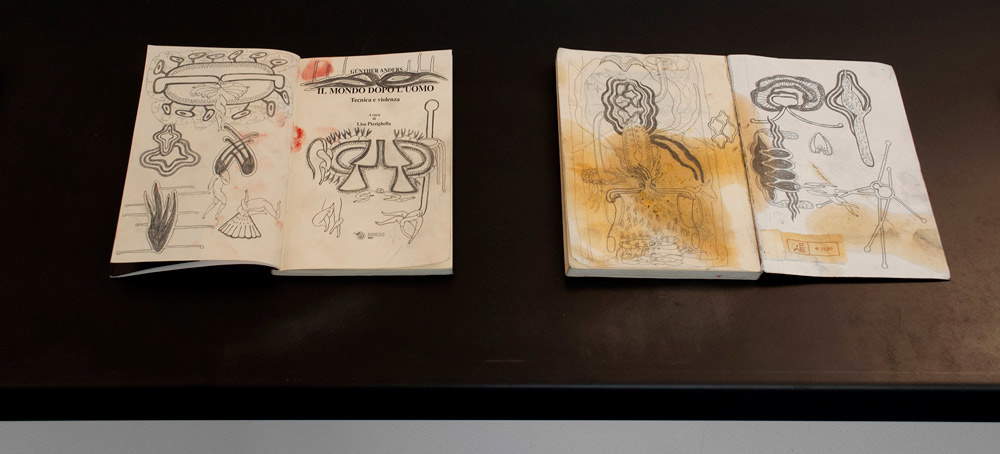

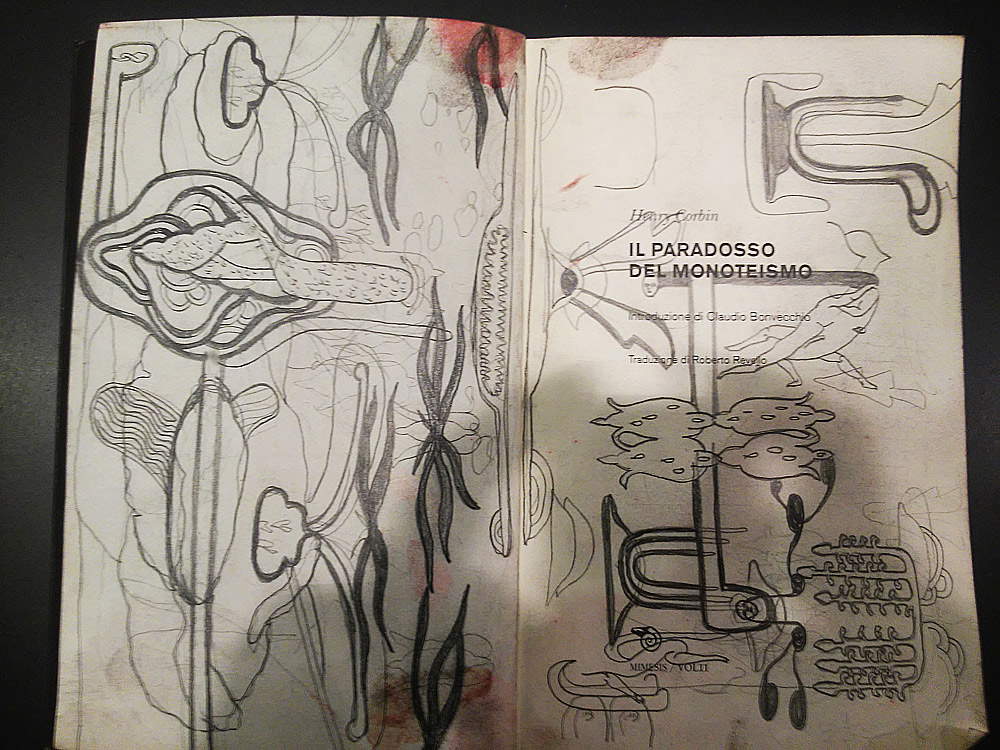

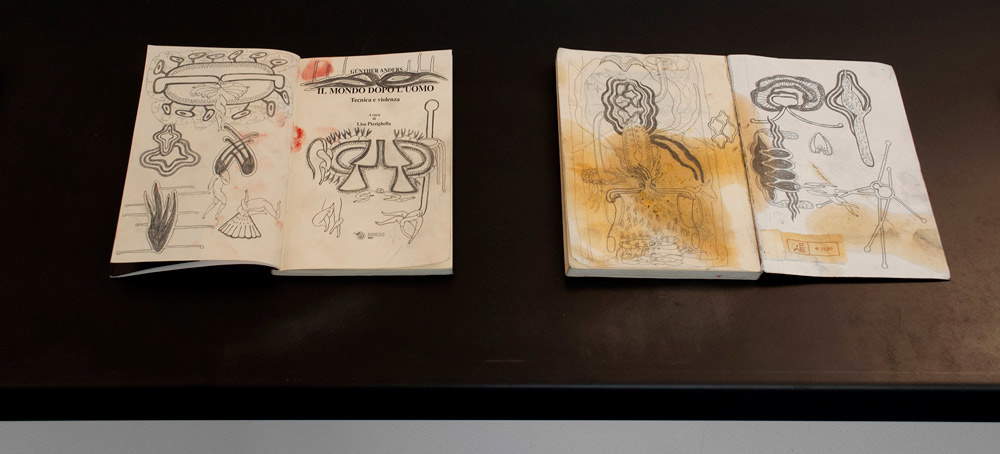

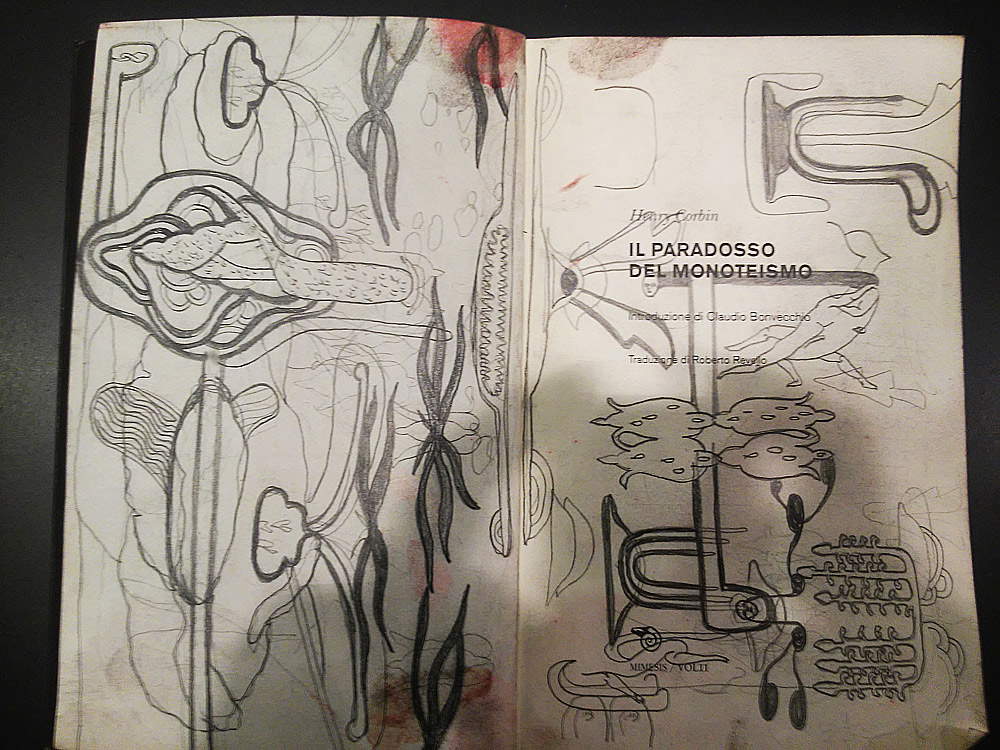

Also on display in the exhibition are the books on which Simone Pellegrini traces his drawings. That of drawing on the pages of books is a practice that the artist has always frequented, and it allows him to fix on paper the first ideas for his larger compositions. Books (Simone Pellegrini shows a particular predilection for mysticism, religion, poetry, philosophy) generate ideas, and ideas are immediately fixed on their very pages, even without there being a direct reference to what emerged from the reading: Simone Pellegrini’s art, Viviana Scarinci pointed out, has no debt of gratitude to the book, since the artist “defends the purity of his vision” even from those very pages that often constitute the springs of his figurative universe. However, one could not fully understand Simone Pellegrini’s art without knowing these drawings, which appear almost instinctive to us, but which are actually the result of thoughtful elaborations: because the artist’s imagination is often stimulated by words. Which are nothing but signs themselves (a language, in every way similar to that which the artist tries to create by means of figures). They are, moreover, profoundly different products than the works intended to be hung on the walls. For in those books the artist comes into direct contact with the support. This is not the case in the larger works, since the latter accommodate impressions that originate from matrices that Simone Pellegrini, as anticipated, will later dispose of. And it is interesting to note that the matrix, the object on which Simone Pellegrini directly intervenes, is at the same time the part of the work destined for destruction, for sacrifice.

Sacrifice is an integral part of the work since, as the artist often points out, his research is aboutman, his involutions and evolutions, which necessarily involve upheaval, struggle, destruction and rebirth. What we see in Simone Pellegrini’s maps is a universe that meets and clashes, and where the human body, as in medieval treatises, almost comes to identify itself with the cosmos itself, but the Marche artist’s approach is contemporary: “the expressions of contemporary art,” Pietro Gaglianò further explains, “have borrowed in countless declinations” the reciprocity between the celestial and the terrestrial “stripping it each time of transcendence and bringing it back to the experience of life.” His is a research that probes the primordial of man, cloaking itself in symbols that seem to pertain to the sphere of the sacred, but maintaining a perspective that is always “consistently anthropocentric” and that “does not seek an audience,” does not intend to communicate with “a precise community that shares its language,” because, Gaglianò continues, he intends to dilate his own historical time.

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Andante causato (2017; mixed media on paper, 108 x 210 cm) |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Andante causato, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Andante causato, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Andante causato, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini’s Ostrakon exhibition. Ph. Credit Cardelli and Fontana Gallery, Sarzana |

|

| Simone Pellegrini’s Ostrakon exhibition. Ph. Credit Cardelli and Fontana Gallery, Sarzana |

|

| Drawings on books by Simone Pellegrini |

|

| Drawings on books by Simone Pellegrini |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Background Conditions (2017; mixed media on paper, 127 x 230 cm) |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Background conditions, detail |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Diaphanous Miscellaneous (2017; mixed media on paper, 95 x 165 cm) |

|

| Simone Pellegrini, Diaphanous Vario, detail |

Simone Pellegrini’s work, in essence, stands outside of time. And in this sense, too, the fundamental primitivism of his compositions should be read: a primitivism that, however, in its dimension of research on man and not research on art, likens him more to a Piero di Cosimo than to an early twentieth-century avant-gardist. For such reasons, his investigation does not even seek the beautiful, and makes use of few tools. His cryptic art seems itself founded on procedures that appear ritualistic to us. Few signs, repetitive, that always repropose the same, meager chromatic range (red, black, sepia: after all, the oldest colors used by man to produce art) and that assume a universal value. Drawings that are “like burnt sinopias, traces dun otherwise graceful epos, between flavor of popular freshness and watermarks of rising myth” (thus Flaminio Gualdoni). Dense and vigorous drawings, which even in the stroke suggest that carnality that permeates every composition by Simone Pellegrini.

An essentially visionary art, filled with distant myths, traces of lost civilizations, prehistoric colors, tangles of fertile limbs that express a full sexuality, constructions that preserve the memory of ancient cosmologies. Works in which all narrative intent is lost. Works that are anything but immediate, and that require a slow, reflective and thoughtful fruition, in tune with their genesis. Works where everything is constant metamorphosis.

Simone Pellegrini was born in Ancona in 1972 and currently lives and works in Bologna. He graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Urbino in 2000, but has been exhibiting his works since 1996. Since 2003 he has collaborated with Galleria Cardelli and Fontana in Sarzana and, since 2006, with Galerie Hachmeister in Münster, Germany. He has exhibited in several exhibitions in international contexts (among them, three editions of the Venice Biennale, in 2015, 2013 and 2011, as well as world-renowned fairs and important group exhibitions) and has held solo shows in Italy and abroad. His works can be found at MAMBo in Bologna, in the permanent collection of Bologna Fiere, at the Volker Feierabend Collection in Frankfurt am Main, in the Civic Museums of Monza, in the collections of Palazzo Forti in Verona, and in many other collections. He is also a teacher of Painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Bologna.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.