The Three Graces by Antonio Canova: beauty and sensuality

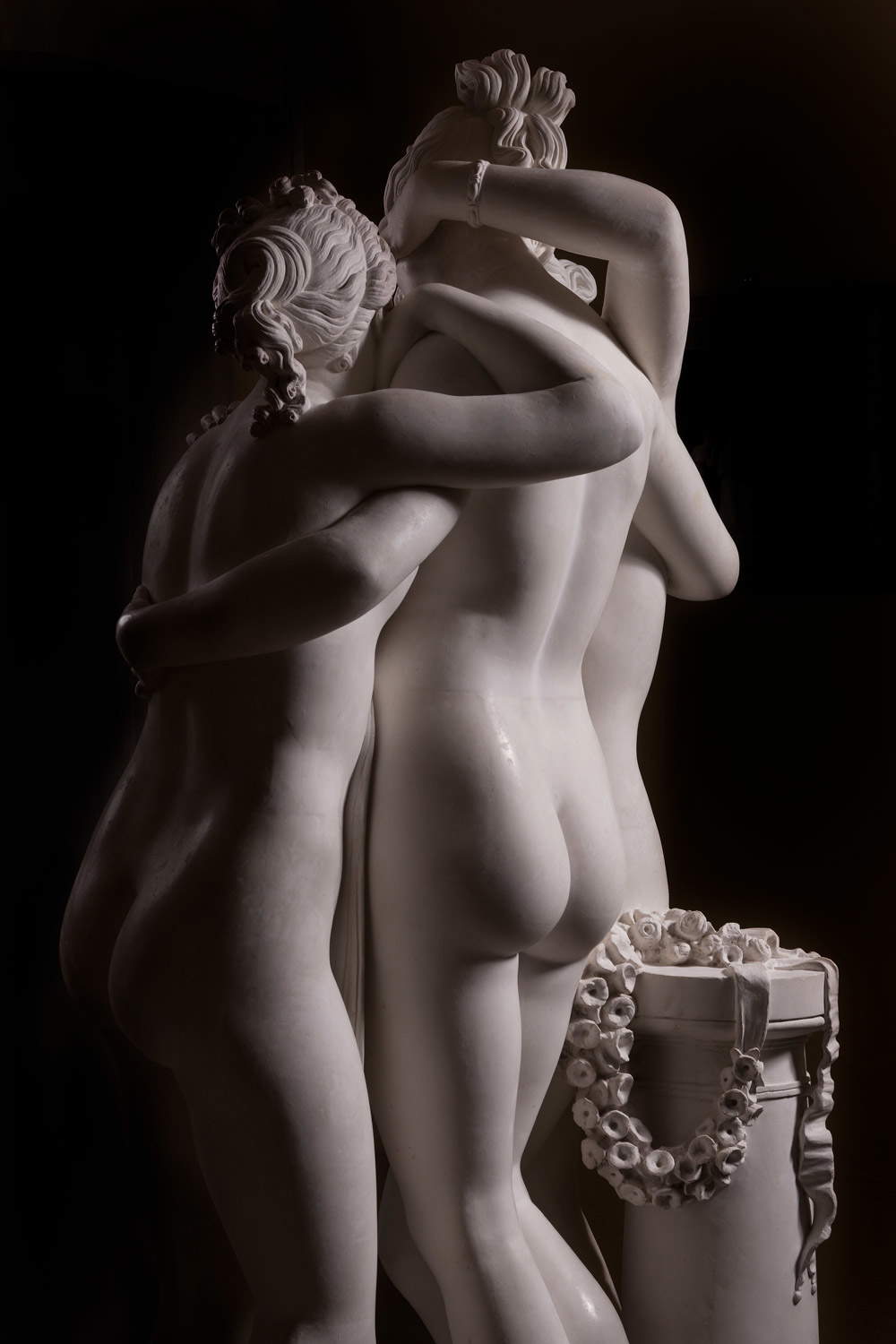

A symbol of grace, beauty and sensuality, the sculptural group of the Three Graces by Antonio Canova (Possagno, 1757 - Venice, 1822) is considered among the finest masterpieces of art of all time. The three nude female figures unite their slender, toned bodies in an embrace, look into each other’s eyes, caress each other gently, and almost abandon themselves to each other, making lascivious movements transpire in the eyes of the observer. A single drape, which first wraps around the elbow of the young woman on the right and which she then supports with her left hand, grazing a breast of the central figure with her fingers, covers the nudity of all three. It is a harmonious trio as a whole; it seems as if the polished marble of which the three figures are made comes to life in front of the viewer, who is attentive to catch every detail of the great sculptor’s mastery. It seems to see their tapering fingers move across the smooth, soft skin, their delicate faces come closer, and to see them clasp each other lovingly. All three similar in build and hairstyle typical of the period, the female figure in the center is frontal, embracing both her companions and tilting her head slightly toward the figure on the left, who invites her to do so with a gentle caress; the latter gently turns her gaze toward the central figure, with one hand brushing her face, the other resting it on the shoulder of the third maiden. The latter, in turn, is placed opposite the young woman on the left and, as she looks at her and smiles, she brushes the breast of the central one and rests her other hand on her shoulder. They all stand on one leg, keeping the other half-folded and resting only their fingers on the ground, either behind or crossed to the supporting leg, and are arranged around a sacrificial altar on which is placed a floral garland.

The first and most famous version of the sculpture, made between 1813 and 1816, is now housed in theHermitage in St. Petersburg, while a second version with minor differences is kept in London’s Victoria & Albert Museum. Before outlining the history of both versions, however, it is worth pointing out who the three Graces were. Daughters of Zeus and the nymph Eurinome, they were deities connected with the worship of nature and vegetation, but above all they were the goddesses who bestowed grace, beauty and joy on nature, the gods and mortals. They danced, presided over banquets and usually accompanied Aphrodite and Eros, deities of beauty and love, and with the Muses danced to the sound of Apollo’s lyre for the gods. It is the Greek poet Hesiod who mentions the names of the three Graces in his Theogony: Aglaia, Euphrosyne and Thalia. These were able to offer a particular gift to humanity: splendor, joy and prosperity, respectively. Consider, for example, their significant presence in Botticelli’s Primavera, where the three maidens dance harmoniously covered only by transparent veils between the god Mercury and the central figure always identified with Venus, accompanied by Cupid shooting an arrow; all in a natural setting with fruit trees and a flowering meadow. And it is Giorgio Vasari himself who, in describing Botticelli’s painting, speaks of a “Venus who graces her blooming, dinotating spring,” thus as goddesses connected to nature and to whom so much beauty, joy and prosperity is owed to nature and the gods.

Antonio Canova, The

Antonio Canova, The

It is noteworthy, however, that in Botticelli’s Primavera or, for example, in Raphael ’s The Three Graces from the Condé Museum in Chantilly, the three Graces are arranged, in keeping with the iconography of classical antiquity, with the central figure turned away from the viewer and the other two taken in profile or facing the viewer. Instead, Canova chooses to depict the three maidens in an innovative way, all facing frontally, with none of the three turning their backs to the viewer and all looking at each other with transport. The young woman in the center and the one on the left seem to look dreamily at each other, while of the one on the right we catch the participation. While still responding to the canons of ideal beauty that characterized the aesthetics of Neoclassicism theorized by the German Johann Joachim Winckelmann, according to whom ideal beauty was summed up in the formula “noble simplicity and quiet grandeur,” thus in the rational pursuit of forms far removed from virtuosity but characterized by the elegance and grace of classical art, Canova’s three Graces are far from devoid of human feeling, but on the contrary convey in the viewer a strong emotional involvement: a sensuality bordering on lasciviousness, as King Ludwig of Bavaria had to write after observing the Venetian sculptor’s Graces, and for that reason he did not prefer them. What struck him positively, however, were the Graces of Bertel Thorvaldsen (Copenhagen, 1770 - 1844), which were more chaste than those of his “rival.” The Danish artist’s sculptural group, made between 1817 and 1819 and now housed at the Thorvaldsens Museum in Copenhagen, is often compared with Canova’s because, although both are neoclassical works, there is a substantial difference between the two: Thorvaldsen’s Graces, in full compliance with neoclassical aesthetics, do not show any feelings; although they embrace, look at each other and brush against each other (the young woman on the right touches the chin of the central one with her finger), no erotic intent is apparent. Their gaze is fixed, their faces impassive. Little more than children, unlike Canova’s who are instead well-formed and comely, they look like three teenagers intent on innocent play. Thorvaldsen also adds to the three Graces, at their feet, on the left, a Cupid playing the zither, probably to fill the space between the young girls’ legs, while on the right he places a small column; in the Canova group, on the other hand, the legs of the maidens brush against each other, suggesting a certain sensuality. Thorvaldsen’s and Canova’s Graces thus represent two opposite ways of understanding beauty: human and sensual that of Canova, divine and chaste that of Thorvaldsen.

The three Graces, carved from a single block of marble and life-size, were commissioned from Canova by Josephine de Beauharnais, the divorced first wife of Napoleon Bonaparte. It is likely that the proposal to work on a sculptural group depicting the three Graces came to the sculptor in a letter sent on June 11, 1812 by the former empress’s secretary, J.M.Deschamps, to which Canova replied asking for time to reflect; however, from several sketches and drawings it seems that the sculptor set to work on this theme almost immediately. According to Massimiliano Pavan’s reconstruction, in 1812 the painter and collector Giuseppe Bossi had written to Canova, “I have heard rumors that you should make for this Lady [the Beauharnais] a group of the three Graces.” She actually did not have time to see the finished work because she disappeared in May 1814, and neither did a drawing of the group, for which the sculptor already said he was sorry in 1813, when Leopoldo Cicognara wanted to go to Paris to bring Napoleon the first volume of his History of Sculpture. Ugo Foscolo also wrote to Cicognara, anticipating, “To you orator of the Graces, I will send before long the Carme delle Grazie,” which the poet dedicated to Canova.

Antonio Canova,

Antonio Canova,

After the death of his mother Josephine, her son Eugene de Beauharnais followed the commission, but a long period of time passed before Canova received payment. The sculptor had to wait until March 1817 to obtain the agreed sum, which was when Eugene de Beauharnais became duke von Leuchtenberg by marrying the daughter of the king of Bavaria, and at the same time asked Canova for permission to export the sculptural group from Rome. It was then transferred to Munich, where it remained until the mid-1950s. At the Hermitage in St. Petersburg it arrived there in 1901 with its sale by the descendants of Eugene’s son, Duke Maximilian von Leuchtenberg, and his wife Marija, daughter of Russian Tsar Nicholas I. The couple had settled in St. Petersburg, and after Maximilian’s death in the mid-1950s, the family collection was moved to Russia and placed in the Mariinsky Palace. Instead, the original plaster cast is kept in the Gypsotheca in Possagno and bears the inscription “Begun in June finished in August 1813.”

There is also a second version of the Three Graces, now in the Victoria & Albert Museum in London and made between 1815 and 1818. This was commissioned from him by John Russell, 6th Duke of Bedford, who after visiting the sculptor’s studio in Rome and being fascinated by the work Canova was still working on, wished to purchase the finished work. Eugene de Beauharnais also wanted to purchase the sculpture commissioned by his mother, so the sculptor offered to make a replica of the first version with modifications for the Duke of Bedford. After accepting the proposal, the duke wrote to Canova that he had never seen anything in ancient or modern sculpture that gave him more pleasure, and that despite the modifications he hoped that the true grace that distinguished the work would be preserved. A white rather than veined marble was chosen for this second version, the rectangular altar at the back was replaced by a circular column with a Doric base and capital, and the central figure was given a slightly enlarged waist. When the sculpture was finished, it was delivered to the duke’s country residence, Woburn Abbey; extremely enthusiastic about the new acquisition, the Duke of Bedford was struck by the softness of the three Graces, “that aspect of vivid softness given to the surface of the marble, which seems to want to yield to the touch.” At the mansion, the sculpture was placed in the Temple of Graces, a rotunda lit from above specially designed by architect Jeffrey Wyatville. Canova himself, during a visit he made to Woburn Abbey in 1815, before this new space was built, reportedly recommended the correct location and lighting to use for his work. This was placed on an antique marble pedestal that allowed the viewer to admire the sculpture from multiple vantage points.

Ugo Foscolo wrote in his unfinished poem Le Grazie: “Al vago rito / vieni, o Canova, e agl’inni. [...] Perhaps (o ch’io spero!) artefice di Numi,/ nuovo meco darai spirto alle Grazie / ch’ora di tua mano sorgon dal marmo.” And so the Venetian sculptor gave life to one of the greatest masterpieces of Neoclassicism.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.