The theft of the Mona Lisa: when Vincenzo Peruggia stole Leonardo's famous painting

And now give us back the Mona Lisa. Who among you does not get a smirk on their face as they recall this slogan! Yet the French are innocent, and the rocambolic story of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa can confirm this.

Between 1502 and 1503, Leonardo was in Florence and willingly accepted the offer of the merchant Francesco del Giocondo, who, in an effort to flaunt his social ascendancy, commissioned him to paint a portrait of his wife, Lisa Gherardini. The merchant, however, had not reckoned well with the master’s well-known mania for perfection, who worked on the painting for a full four years; in 1507 he took it with him to Milan and continued to retouch it again until 1513. Moral of the story: the portrait was never delivered to the del Giocondo couple; in fact, in 1517 it even took off for France. Leonardo took it with him to Amboise when he was called to work as court painter to King Francis I, and after his death the Mona Lisa became part of the French royal collections, only to be transferred from time to time to the various residences of successive sovereigns, until it landed in the museum symbolic of the revolution, the Louvre, without attracting particular attention. Napoleon moved it again to adorn Joséphine’s bedroom at the Tuileries, but it returned shortly thereafter to the Louvre where artists and writers-by now in the height of the Romantic temperament-began to look at Mona Lisa with different eyes. In the collective imagination, the woman with the sardonic smile became the epitome of female sensuality, a femme fatale, shrouded in an aura of mystery and alchemy, as indeed was the case with her author, an artist, scientist, genius, almost magician.

The painting’s fame then grew by leaps and bounds as a result of this singular affair: on the morning of August 22, 1911, the French painter Louis Béroud had gone early in the morning to the Louvre, closed to the public as he did every Monday, to do his work as a copyist. He had intended to portray the Mona Lisa specifically. But as he arrived in front of the wall, he found that the painting was not there. In front of him the wall was empty and the painting gone.

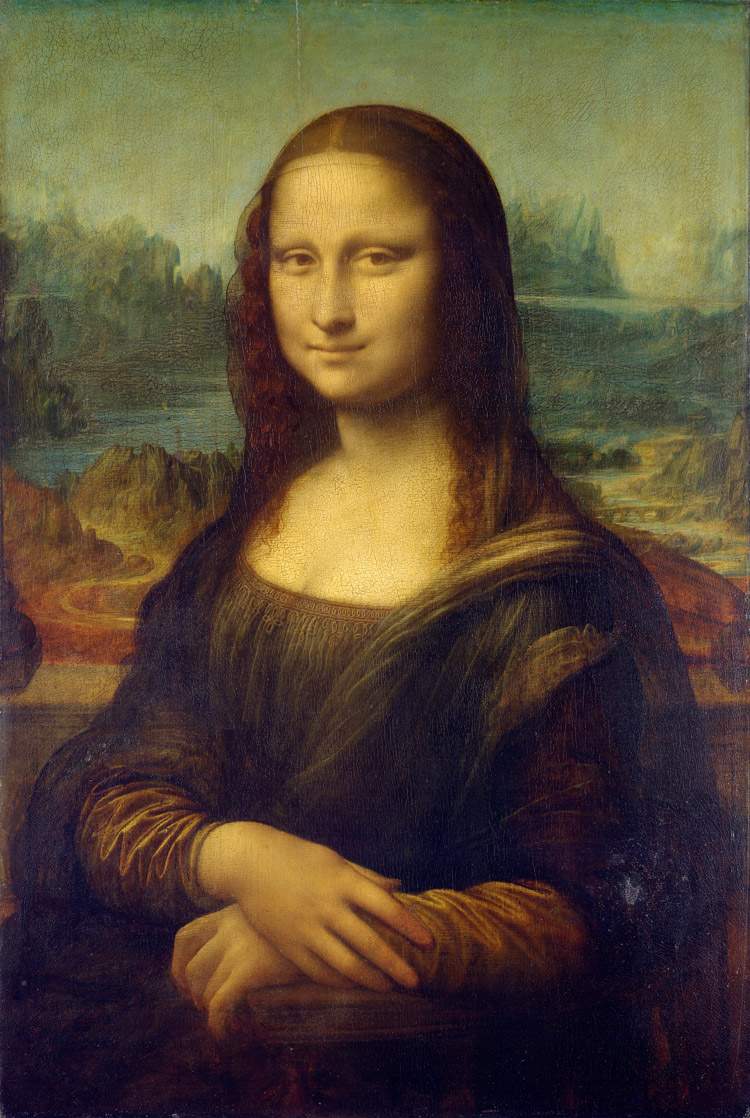

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa (c. 1503-1513; oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

Those moments are recounted in an article published in Le Figaro, in the August 23 edition. At first, Brigadier Poupardin, alerted by Béroud, thought that the Mona Lisa had been moved to the Braun photographic studio, from which the Louvre was supplied and which was authorized to transport the works to photograph them (on the condition that they not be moved during the museum’s opening hours to the public). However, the painting was not in the studio, and it had to be realized that it had been stolen, and that all that remained of the work was the frame and glass, abandoned by the thief inside the Louvre. The halls were evacuated, all museum doors were closed, and the staff was immediately summoned for the first ritual interrogations.

This was the first major theft of a work of art from a museum-the heist of the century. Immediately the French police began questioning everyone who had been in the Louvre during some maintenance work, but to no avail. Some suspicions fell on a group of workers who had been seen in front of the Mona Lisa the previous day, on Monday (already then a day when it was closed to the public), but it turned out that they were clean. Apollinaire and Picasso (the former also arrested) were then suspected of having always expressed a desire to empty museums and fill them with their works. Obviously these were artists’ megalomanias. The French authorities were even thinking of a coup d’état by the Germans, who were not only trying to steal their colonies in Africa, but were also trying to despoil them of their masterpieces. In short, the pages of the newspapers talked at length about the affair, and the Louvre remained distraught and without its Mona Lisa for a good two years, until 1913, when the painting appeared in Florence.

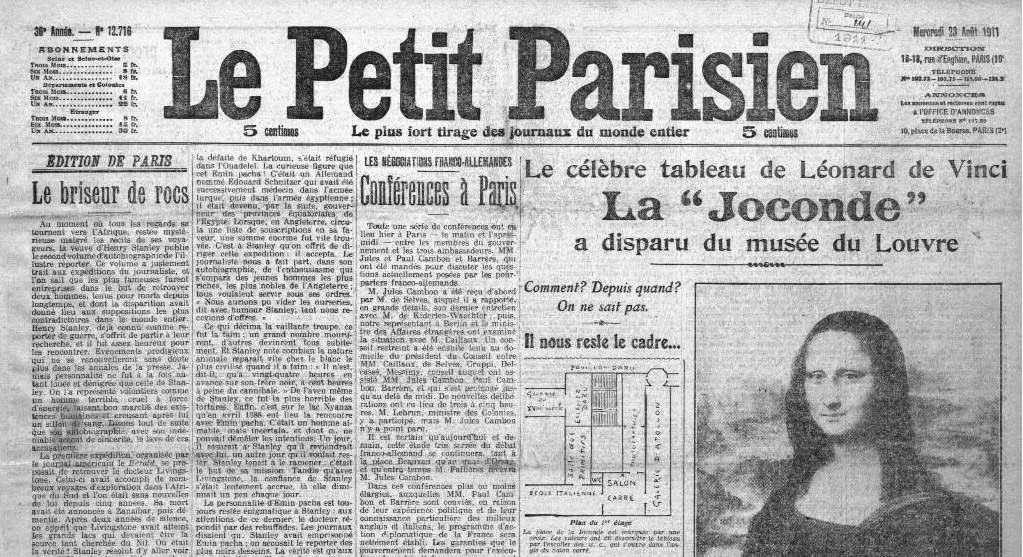

|

| The theft of the Mona Lisa on Le Petit Parisien |

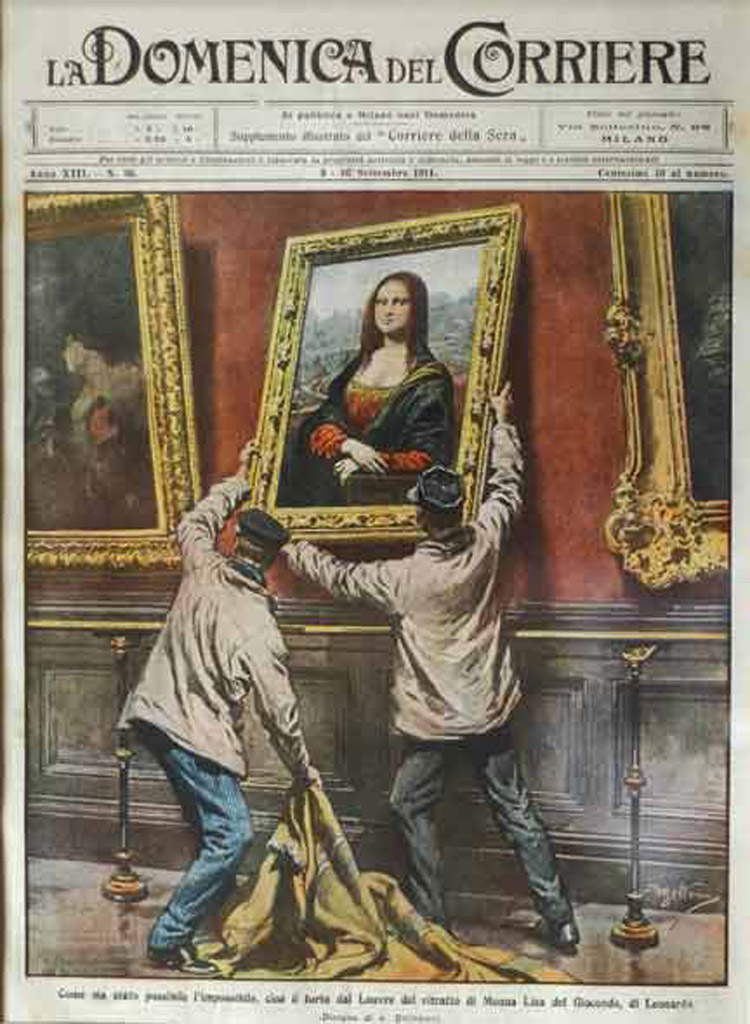

|

| The theft of the Mona Lisa in the Domenica del Corriere |

Recounting the circumstances was, some time later, the Chronicle of Fine Arts. On November 24, a Florentine antiquarian, Alfredo Geri, received a letter, signed Leonardo V., in which he was offered to buy the Mona Lisa itself. We would be very grateful if by your work or that of some of your colleagues, this darte treasure would return to the homeland and especially to Florence where Mona Lisa was born, and that we would be in ispecial way glad if one day in the future and perhaps not far off it would be exhibited in the Uffizi Gallery in the donore place and forever. It would be a nice revenge to the first French empire, which, scaling in Italy, laid its hands low on a great quantity of darte works to create for itself in the Louvre a great museum: this was what the phantom Leonardo V. wrote to Geri in the letter. Lantiquario pointed it out to the director of the Uffizi, Giovanni Poggi (Florence, 1880 - 1961): together they arranged to meet with Leonardo V.: the meeting was set for Dec. 11 at Geri’s store. From there they would then move on to the hotel where the strange character was staying and where he had hidden the painting. In their presence then appeared the fearless Lupin, who was none other than an Italian painter, Vincenzo Peruggia (Dumenza, 1881 Saint-Maur-des-Fossés, 1925). Our compatriot, unaware of the collecting history of the work, had had the noble as well as absurd idea of returning to Italy the masterpiece he thought had been stolen from us by Napoleon.

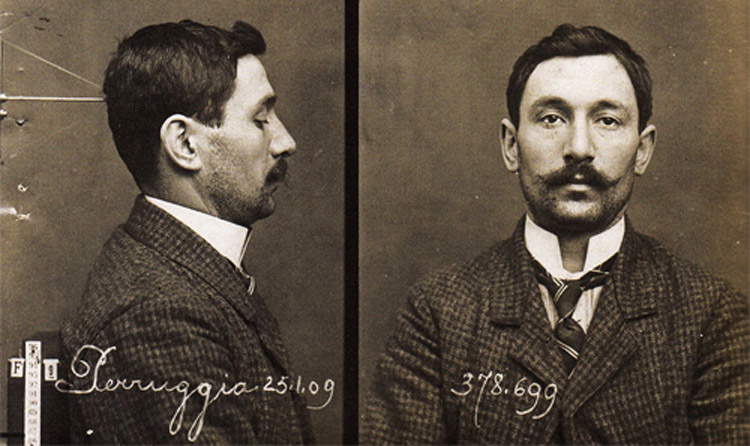

|

| Photo by Vincenzo Peruggia |

The director of the Uffizi, having ascertained that this was the real Mona Lisa, notified the authorities, and the prefect had the thief arrested. During his interrogation, Peruggia recounted that he had worked at the Louvre: he himself had assembled the case that held the painting. When he decided to engineer the theft, it was easy for him to enter the museum because he knew how to evade surveillance. He spent the whole night holed up in the closet, then early in the morning, he disassembled the display case, took the painting, wrapped it in his coat and went out undisturbed. He even took a cab back to the Parisian guesthouse where he was staying, locked the painting in a suitcase that he hid under his bed, and there he was confined without arousing any suspicion for a full 28 months.

The trial took place in June 1914 in Florence (by that time, the Mona Lisa had returned to the Louvre). Peruggia, to whom it was moreover recognized that he was suffering from mental illness and consequently that he was not a danger to society, was sentenced to a year and a half in prison, but his naiveté aroused sympathy among the public, who would have liked a more lenient sentence for him.

|

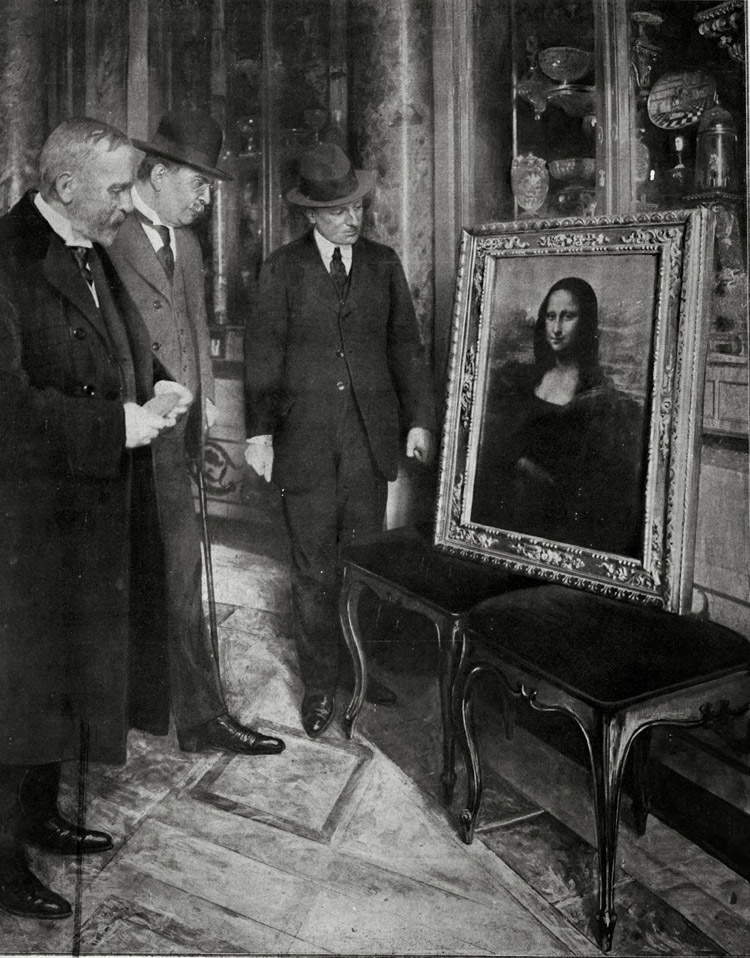

| The director of the Uffizi, Giovanni Poggi, looks at the Mona Lisa |

|

| The Mona Lisa at the Uffizi |

|

| The return of the painting to the Louvre |

|

| Vincenzo Peruggia at the trial |

Of course, to recall today the singular story of the theft of the Mona Lisa is in no way to justify the reckless act of theimbianchino Peruggia (who, driven by simplistic patriotism, even expected a thank you and a reward from the Italian state), but only to lead us to reflect on the fact that works of art have often transcended the centuries of history, bringing with them a whole series of complex collector’s vicissitudes and, as often happens, a trail of misleading false myths that are hard to die (I refer to a previous article in Finestre sull’Arte); moreover, most of the works had the most disparate uses and were not made to have as their purpose exhibition in a museum, an ultimate place in which to land them in order to give them better preservation and enjoyment by the public.

Reference bibliography

- Pietro C. Marani, Leonardo. The Mona Lisa, Giunti, 2014

- Enrica Crispino, Leonardo, Giunti, 2002

- Donald Sassoon, Becoming Mona Lisa: the making of a global Icon, Harcourt, 2001

- The discovery of the Mona Lisa in Cronaca delle Belle Arti, supplement to Bollettino dArte, January 1914, no. 1

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.