The temples of Paestum in the engravings of Giovanni Battista Piranesi

The temples of Paestum had really had it rough in the 1740s. At that time, in fact, the King of Naples, Charles III of Bourbon, had recently begun some rearrangement work at the Royal Palace in the Neapolitan city, and one of the court architects, Ferdinando Sanfelice (one of the best and most creative in the kingdom), had proposed to obtain the materials for the construction from the columns of the temples. Here is what he wrote in a letter addressed to the sovereign: “to advance time and expense, one could take the stones that are in the ancient City of Pesto, which was an ancient colony of the Romans, where there are so many quantities of half-destroyed buildings, there being more than a hundred columns of immense size with their capitals, architraves, friezes and cornices of such large pieces that they make known the power of the ancient Romans; these could be transported with great faculty by sea, the said City being built near the Marina.” After all, it is known that, at that time, there was not much sensitivity to ancient things, and the fact that a modern architect like Sanfelice hypothesized to make Paestum a kind of quarry for the fabrication of the Royal Palace should not be so surprising. However, it is also necessary to point out that even then the climate of enthusiasm for the ruins of ancient cities that would later lead to the birth of neoclassicism was beginning to spread: in 1738 the ruins of Herculaneum were discovered, and in 1748 those of Pompeii. And in such a climate, the revaluation of Paestum would not be long in coming.

So having fallen into oblivion, Sanfelice’s proposal (thankfully), the groundwork for making the temples of Paestum known to the world arose shortly after 1746, when a young Neapolitan architect, Mario Gioffredo, visited Paestum and made surveys that he then sent to the court of Charles III. The government of the kingdom of Naples, for its part, had in the same years had the idea of starting the construction of a road that could improve connections between the kingdom’s capital and areas further south, toward Calabria: the new road, much of whose route today is traced by State Road 18, passed right by the temples of Paestum. Thus, perhaps unwittingly, Charles III managed to arouse considerable interest in those ruins: precisely because, as he drove along the new road, they could be admired in all their astonishing solemnity. Thus, Paestum quickly became not only a stop on the Grand Tour, the international journey that acculturated young aristocrats from all over Europe made to discover the roots of European culture, but also became a destination for artists intent on studying the order and harmony of the art of the ancients. Among the travelers who visited Paestum in the second half of the eighteenth century (let us mention just a few names: the Marquis de Sade in 1776, John Robert Cozens in 1782, Wolfgang Goethe in 1787) we cannot fail to mention an artist who offered one of the most interesting contributions to the development of neoclassicism, namely Giovanni Battista Piranesi (Mogliano Veneto, 1720 - Rome, 1778).

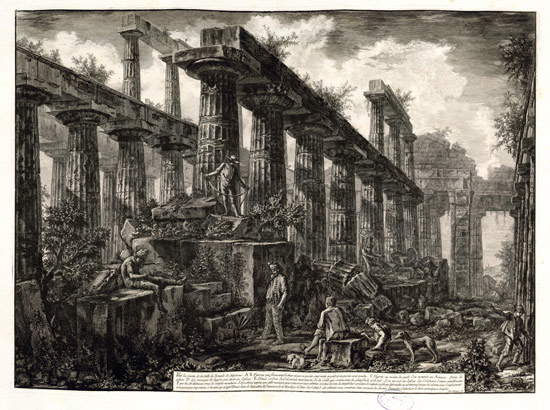

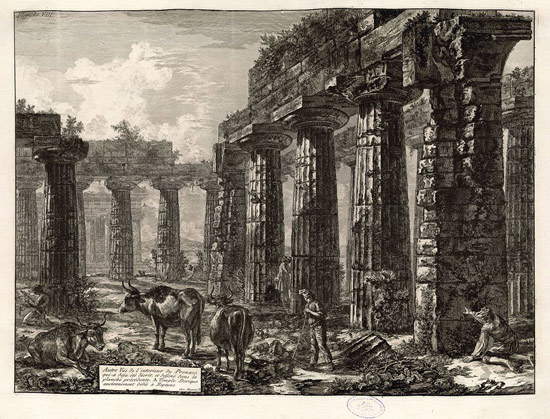

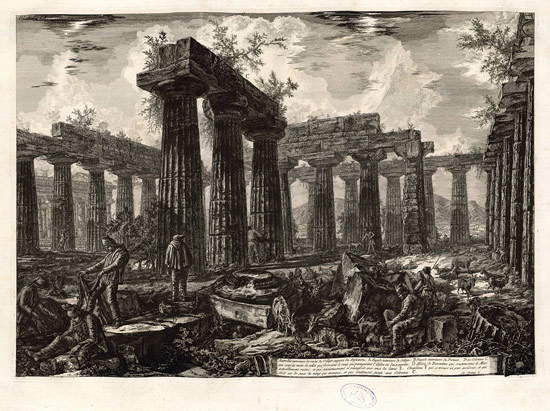

The great Venetian engraver visited Paestum a first time in 1770, and then in the last year of his career and life, 1778, and on that occasion he produced a series of engravings entitled Differents vues de Pesto (“Different views of Paestum”) that had the merit of further spreading interest in the temples of the ancient Roman city. In his engravings, Piranesi offers us precise and meticulous descriptions: the temples are grand and majestic, emerging from a cumbersome thicket and, indeed, are themselves part of it, since the ruins are covered with vegetation and offer shelter to shepherds, peasants, pilgrims, horsemen, and vagabonds of all sorts. The evocative power of Piranesi’s art is such that the temples of Paestum appear almost eerie to us, such is their grandeur and such daring are the perspective views adopted by the artist: we get a sense of the sublime that anticipates even Romanticism. A spectacular grandeur that, moreover, is charged with allegorical meanings: despite their sumptuousness, and despite the idea of opulence that they might suggest, the temples of Paestum, in Piranesi’s engravings, preserve only the memory of what they were, because the present is marked by ruin and decadence, and even the most magniloquent and superb achievements of man must yield to the force of time, which flows by tearing down civilizations, leaving rubble and bringing emptiness and misery even where life prospered happily. In some of these engravings, the presence of the ruins is so suffocating (thanks in part to the skilful use of perspective) that not even the horizon can be glimpsed: the composition is entirely occupied by the columns of the temples, as in the case of the engravings depicting the interior of the Temple of Neptune.

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Remains of the Temple of Neptune at Paestum (1778; engraving, 50.5 x 68.5 cm; Naples, Giambattista Vico Foundation) |

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Interior of the Temple of Neptune at Paestum (1778; engraving, 48.5 x 69 cm; Naples, Fondazione Giambattista Vico) |

The human figures are minuscule when compared to the enormous ruins: one almost gets a sense of impotence from them; it seems that man can do little to halt, or at least slow down, the course of nature, which appropriates what man has made without any regard and obviously proving victorious in the unequal confrontation. And if the austerity of the temples is also suggested by the richness of the details, surprising if we think that Piranesi made these views in less than good health, the human figure acts as a counterbalance, symbolizing also the meanness of the times experienced by the author when compared to the splendid times (in the view of the neoclassical artists) of antiquity: a past, in short, to be looked at with nostalgia. This is what art historian Roberto Pane wrote about the human presence in Piranesi’s views of Paestum: “The characters who wander among the ruins of Piranesi’s views are ruins themselves; almost always tousled men, gesturing by raising their arms, or pointing at something with broad and useless gestures. In reality, their task is only to contribute to the pathos of the representation [...] Perhaps, even through such human wrecks, this poet and, at the same time, rhetorician of Roman antiquity, intended to emphasize the misery of his time, in comparison with the remains of a world that he saw as so fabulous and heroic as to defy even ridicule.”

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Temple of Neptune at Paestum (1778; engraving, 53 x 72 cm; Naples, Giambattista Vico Foundation) |

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the interior of the Pronao (1778; engraving, 49 x 67 cm; Naples, Fondazione Giambattista Vico) |

|

| Giovanni Battista Piranesi, View of the Remains of the Supposed College (1778; engraving, 49 x 67 cm; Naples, Fondazione Giambattista Vico) |

And that Piranesi had a deep admiration for the makers of these temples is also evidenced by the comments affixed by his son Francesco on the cartouches of the engravings when the prints were published. We read, for example, in the long commentary on the engraving depicting a view from outside the Temple of Neptune: “L’exactitude des proportions caracterise ce batiment pour une production de plus parfaites, et des mieux éxécutées dans ce genre, et l’on peut dire que l’Architecte a tiré de son art de quoi s’attirer l’admiration de ses contemporains comme de la posterité.” i.e., “The exactness of the proportions characterizes this construction as one of the most perfect and best executed achievements of its kind, and it can be said that the architect has done so in such a way as to earn the admiration of both his contemporaries and posterity.” Piranesi’s experience would prove to be fundamental, as anticipated, for the developments of neoclassical poetics: the views of the ancient temples of Paestum would become a common feature of many artists who came after him, starting with the aforementioned Francesco Piranesi himself.

All the engravings we have proposed in this article, together with other works, both by Piranesi and by other artists, are on display these days in Naples, at the exhibition Paestum in the routes of the Grand Tour. The Discovery of Ancient Ruins, which is being held at Castel dell’Ovo until May 17, 2016. The exhibition, which is curated by the Giambattista Vico Foundation, puts the ruins of Paestum at the center of the itinerary precisely, investigating their importance for the developments of neoclassicism and as an essential stop on the Grand Tour. Piranesi’s works are but one of the themes that are addressed by a small exhibition, but one that knows how to spread culture and do good outreach around a subject that is perhaps not well known to the general public-and, moreover, for free. For those who are in or around Naples these days, the appointment is not to be missed!

|

| Paestum on the Grand Tour routes. The discovery of the ancient ruins |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.