The Strada Collection: the beauty and fragility of antique glass, a world that enchants

There are countless human discoveries whose history is shrouded in magic and mystery, and one of them is that of the origins of glass, which has its roots in the 3rd millennium B.C. in Egypt and Mesopotamia and is reflected among the pieces in the Strada Collection, a sumptuous collection of archaeological artifacts that preserves one of the most precious nuclei of glass objects from the Roman era known. The Collection, just recently, was acquired by the Ministry of Culture for the National Archaeological Museum of Lomellina in Vigevano. And the legend behind these pieces is the one recounted by Pliny the Elder in the thirty-sixth book of his Naturalis Historia, where he tells how glass was discovered by a group of Phoenician merchants who decided to camp on the banks of the River Bel, Syria, while returning from Egypt with a large cargo of sodium carbonate. Since they had nothing available to support their food preparation utensils, they decided to light a fire under some blocks of saltpeter carbonate. The small fire continued to burn throughout the night, and the next morning the merchants, waking up, noticed that the river sand and sodium carbonate had turned into something transparent and shiny. They had just discovered glass.

This, in fact, is nothing more than a good story because glassmaking was a technique that had been around since the 3rd millennium B.C., and as the centuries passed it only became more and more refined, all the way to the 1st century A.D. To the masterpieces of the craftsman Ennion. This craftsman’s famous cups were made with the fine technique of mold-blowing, exclusive to his workshop. And the pride, in seeing those perfect creations, was so intense that Ennion never failed to stamp his signature on them, a very peculiar and extremely unusual fact for the time.

Soon, however, a cup similar to those of the famous craftsman Ennion, but signed “Aristeas,” went to take away the exclusivity of such production. Aristeas probably came from Cyprus, for in one cup he signs himself “Cypriot,” and this reiteration of his provenance suggests that he moved to the Middle Eastern area from where other objects documented in the Pavia area came.

The Aristeas cup, dating from the second quarter of the first century CE, was found in Albonese, in the province of Pavia, in the late nineteenth century, and is unique not only because it is signed, but because of the five known works by Aristeas, only this one was found whole and in perfect condition. This cylindrical, two-handled, olive-green glass bowl, blown in a tripartite mold and with an extremely modern design, tells us so many stories. It tells us of the dense trade in the early imperial age on extremely functional roads and routes, but it also tells us that it was probably a funerary gift and that is precisely why it reaches us intact. The decoration is closely related to those of Ennion and even the measurements with its height of six centimeters and diameter of nine, are the same as those used by the famous craftsman. In Ennion’s cups, however, the decoration has a single pattern of large pods covering the entire cylindrical part, while in Aristeas’ cup the decoration is divided into three bands. The upper and lower ones repeat the very thin baccellation motif seen by Ennion, but they intersect the taller middle one, which is ornamented with very rich naturalistic friezes. The acanthus giral is, however, an imitation in glass of a motif dear to the typical ornaments of metalware.

The Aristeas cup is the highlight of the Serafini Collection, which in turn belongs to the Strada Collection entrusted to the Museo Archeologico Nazionale della Lomellina in Vigevano. The noble collector Antonio Strada displayed his collection at the Visconti castle of Scaldasole, one of the family estates along with expanses of arable fields. It all stemmed from here: to give continuity to the family farming business, Antonio studied agronomy and graduated from Milan in 1928, and it was from close contact with the fields, which had already yielded important finds during the 19th century, that Strada developed his passion for archaeology and the study of found objects.

“To the artifacts already owned by his ancestors,” explains archaeologist Rosanina Invernizzi, who co-curated (along with Emanuela Daffra, Elisa Grassi and Stefania Bossi) the display of the collection, “Antonio Strada added other nuclei purchased from collectors in the Lomellina area: among them, in particular, the Steffanini collection from Mortara (which included the Aristeas cup) and the Volpi-Nigra collection from Lomello, which also included finds of Magna Greek provenance. Other small nuclei were added over time the result of purchases, gifts or exchanges. There is no shortage, as is often the case in collections, of fake pieces or pieces of dubious antiquity, but on the whole the Strada collection shows us a picture of active exchanges between owners and above all that interest in homeland antiquities characteristic of the years between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.”

He thus began to expand his small collection, which had to adhere to two very specific particularities: that the finds should be within the boundaries of Lomellina and that the recovery of the objects should be accompanied by their study from the manuscripts in the castle. This continuous and feverish acquisition of finds from the territory allowed Antonio Strada to create a true collection of collections, the oldest in Lomellina. A collection of collections with great geographic homogeneity, consisting of 260 objects belonging to a chronological span from prehistory to the Renaissance age, passing mainly through the age of the Romanization of Lomellina (2nd-1st centuries B.C.) and the early imperial era (1st-2nd centuries A.D.).

Placed in the dreamy, older Scuderie del Castello Sforzesco in Vigevano, the collection aims to “bring the objects into dialogue, with the remaining part of the museum, creating a chronological and typographical exhibition path,” Invernizzi says. Thus it starts with the first showcase of the period from prehistory to Magna Graecia; then with some extraterritorial provenances that Strada acquired from the Negri Collection. The tour continues through houses and tombs among metal and terracotta objects, including a Baroque fork and a “whirligig” vase. The peculiar name comes from its shape with a narrow mouth and a very wide body, typical of late Celtic culture. This is a vase, from the second half of the first century B.C. from the Steffanini Collection, made of smooth, purified pottery that served as a container for wine.

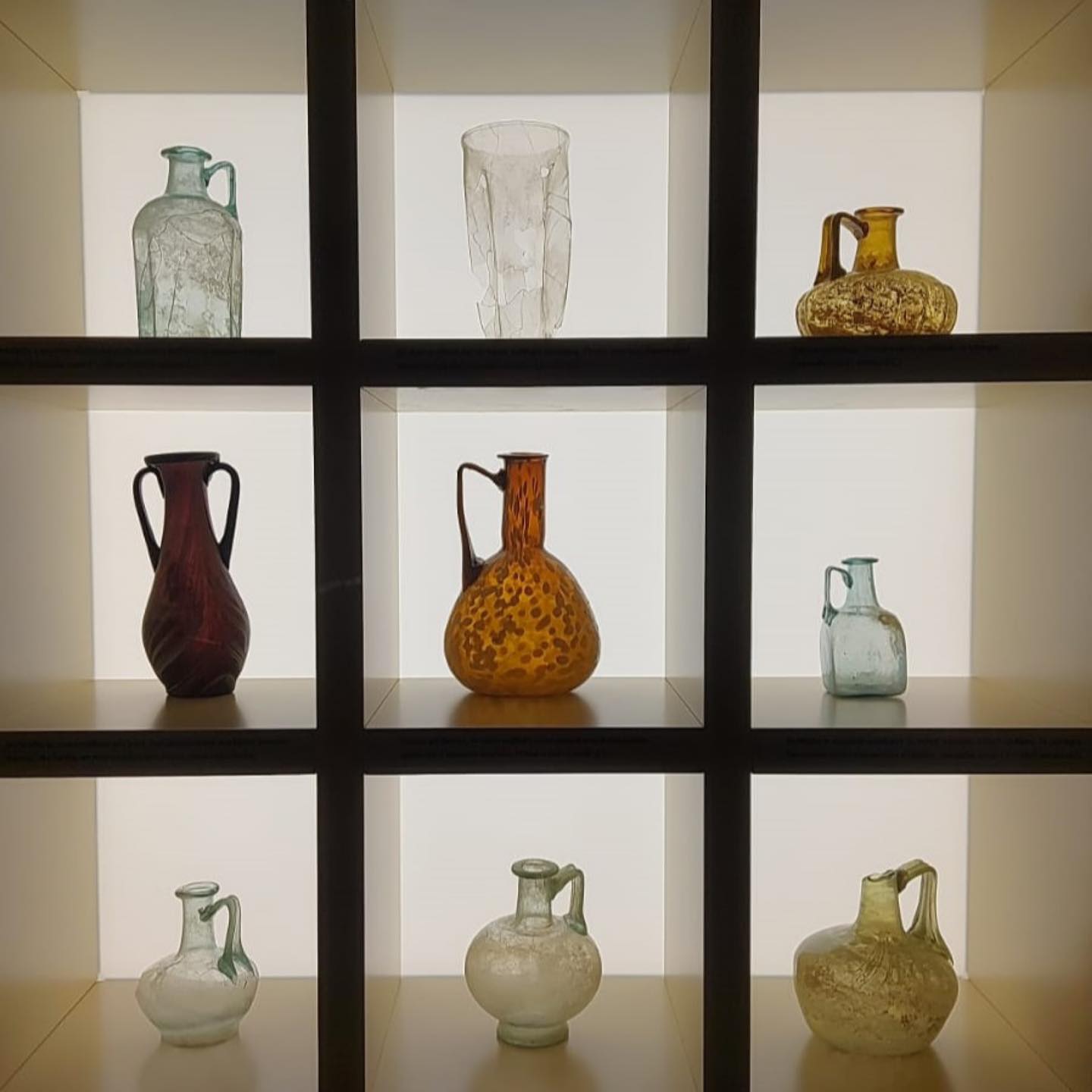

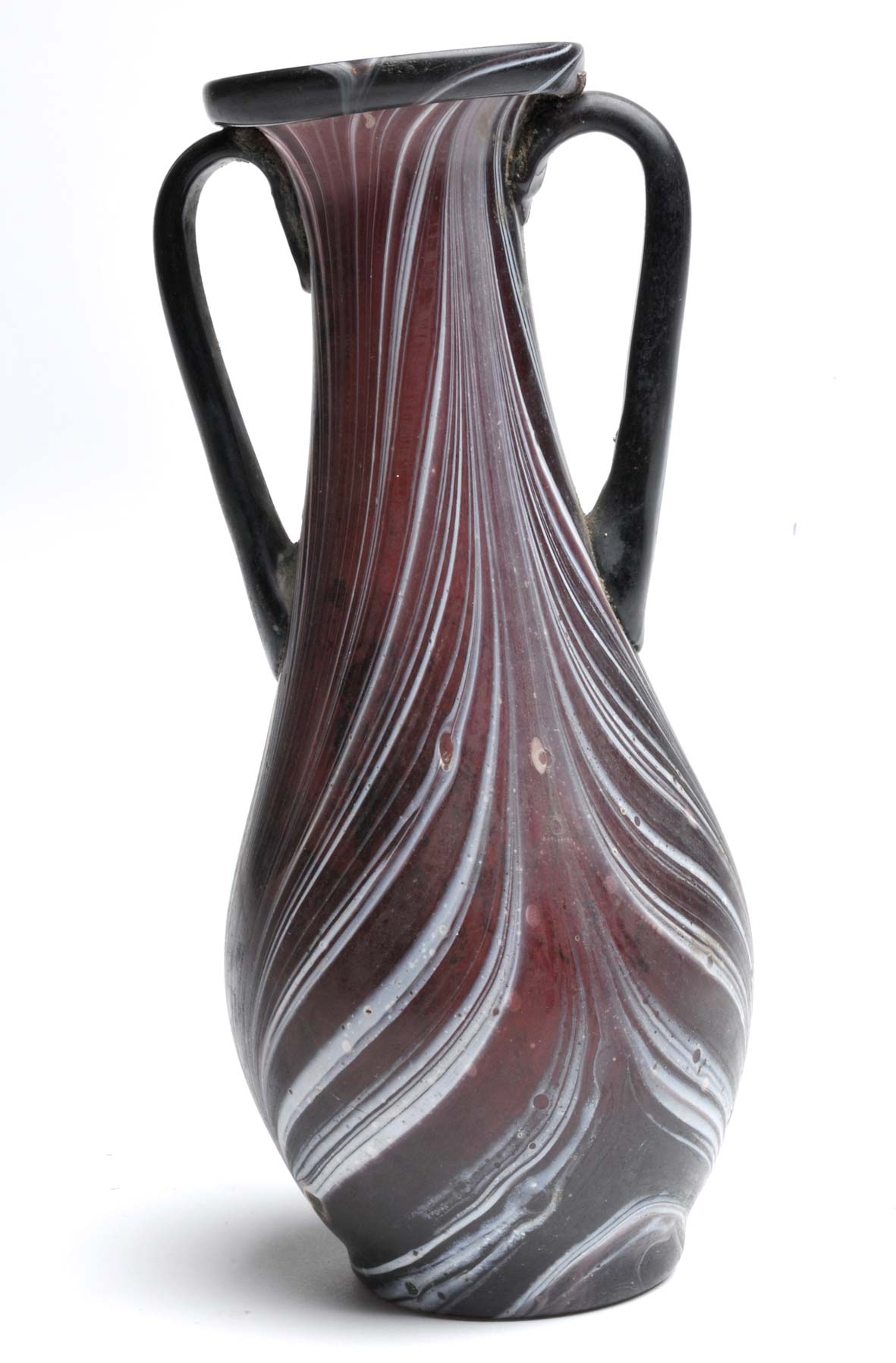

One passes through the area of oil lamps used to light the path into the afterlife and drive away evil spirits, arriving then, behind the cup of Aristeas, at the elegance and transparency of glass containers for food and beauty. A section, this one, that in terms of display and extreme modernity of the pieces on display rivals modern-day design stores. Glassware represents, in fact, the highlight of the collection, especially in terms of the preciousness and rarity of the finds. The objects belong to the Lomellina territory, although we cannot know with extreme certainty that they were worked in this area, with the exception of a balsam bowl purchased in Aquileia.

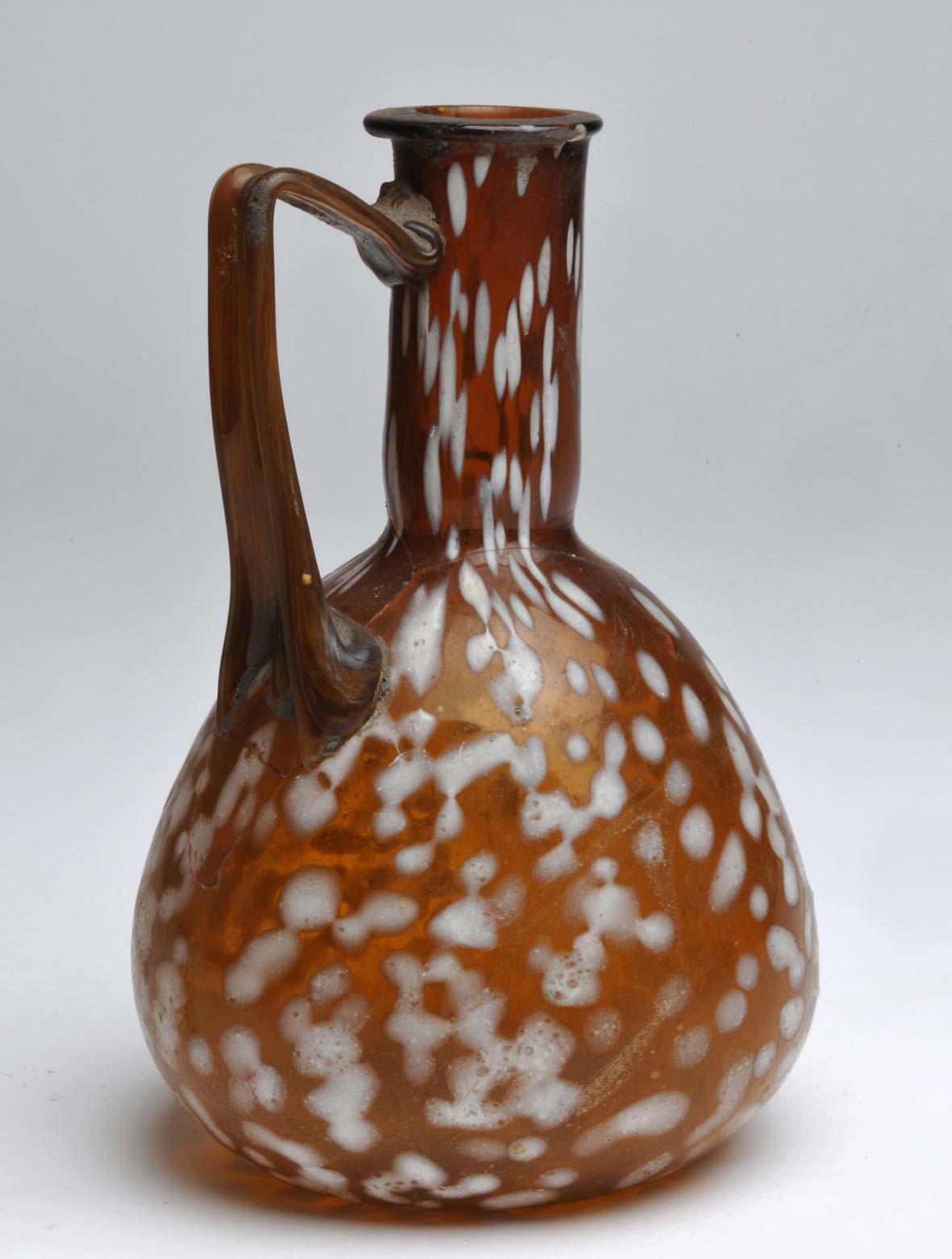

On display are vessels for the table such as finely decorated jugs, as well as containers for ointments and perfumes, peculiar twisted sticks as a symbolic allusion to spinning spools or distaffs belonging to the typically female universe, and above all ribbed cups characteristic of the area. Of particular beauty is a pyriform (pear-shaped) pitcher from the mid-1st century CE, used for serving drinks at the table, precisely because glass was particularly suitable for storing liquids. The pitcher’s intense amber base is interspersed with white decoration made by applying glass beads to the vitreous base and then blowing. This technique makes its surface look extremely irregular and highly modern.

The visit concludes by exploring the showcases of ceramics, from the local tradition to “beautiful service,” from common pottery to more crude but functional ceramics. Belonging to the latter section is an olla from the first half of the first century AD from the Steffanini collection. An object, this one, that could not be missed in every household and was used like a modern-day pot for storing food or cooking soups or the typical puls, a wheat polenta. In addition to cooking, the olla could also be used as a cinerary vessel to collect the ashes of the deceased.

The Strada collection, now on display in the Stable until December 4, 2023 with free admission, will then become part of the museum’s permanent collection allowing visitors to continue to learn and discover that world that had enraptured and enchanted Antonio Strada forever and creating, why not, ever new suggestions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.