The secret that escaped Vittorio Sgarbi: on the busts of Giovanni Antonio Cybei in the Secret Rooms

Vittorio Sgarbi’s Secret Rooms now have very little in the way of secrets; only the furtive gaze of his sister Elisabetta, with the short film Belle di Notte, had allowed us to peek through the rooms, and glimpse the works, of Sgarbi’s private collection, but if it is true, as he himself says, that “the meaning of collecting is linked to the vanity of life,” this secret could not remain so for long.

The treasures of the Cavallini Sgarbi Collection, accumulated over the years thanks to an assiduous mother-son collaboration, have been on display since 2016 in a continuous exhibition that began in the Marche region and then became a traveling exhibition, almost like a long theatrical tour, moving roughly every six months.Vittorio Sgarbi’s Lotto Artemisia Guercino, The Secret Rooms began its wanderings from the rooms of Palazzo Campana, in Osimo, in March 2016, and then landed in Cortina d’Ampezzo in December, just in time for the start of the winter season. In the spring of 2017 the collection arrived in Trieste, going to occupy the striking Salone degli Incanti, the city’s former fish market; just a few days ago, with the title just changed to Dal Rinascimento al Neoclassico, Le Stanze Segrete di Vittorio Sgarbi, the exhibition then opened at the Castle of Novara, fresh from a long and very recent restoration. In 2018, a stop in Ferrara is already planned, which for the occasion will open the doors of the Castello Estense, future home of the Pinacoteca Comunale, to the popular fellow citizen; for 2019, there are rumors of a descent to Matera, in the year the city will be European Capital of Culture, and they are already looking beyond, thinking of a permanent exhibition venue for the works.

Noting the considerable size of the material (there is talk of a corpus of at least 3,000 art objects), there should be no shortage of subjects for these continuing events, but those expecting a rotation will see their hopes dashed; the differences between one exhibition and the next have so far been minimal if not nil, and the only catalog available (if you can find one) remains the one printed for the Osimo exhibition. No real secrets, then, about the contents of the collection, at least as far as that hundred or so works, including genuine masterpieces, are exhibited and presented, commented on, photographed, and well researched in the relevant catalog.

The world of art, on the other hand, never fails to reserve some surprises, and a couple of these precious artifacts hold a “secret” that Sgarbi himself has remained in the dark about, at least until now. Alongside the various Guercino, Lorenzo Lotto, Pietro Liberi and Artemisia Gentileschi, among the regular protagonists of these exhibitions are two marble busts, particularly dear to their owner, catalogued as “Portraits of the Masetti brothers from Bagnano,” and attributed to a sculptor as well known in life as forgotten today: Giovanni Antonio Cybei (Carrara, 1706 - 1784).

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei, the two marble busts in the Cavallini Sgarbi Collection (details of the individual busts in the following photos) |

Vittorio Sgarbi has repeatedly declared himself a “fan” of this artist neglected by critics, a leading figure in sculpture at the height of the eighteenth century and the first director of the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara, his hometown; there are not a few occasions on which the well-known critic has lavished praise on Cybei, calling him from time to time the sculptor I adore (2002), great, exceptional, but totally unknown (2002), extraordinary artist totally forgotten, excluded (2015) praising his skill “it is incredible the quality of this artist” (2001) and, without sparing really challenging comparisons,I consider him as great as Canova (2016).

During a visit to Carrara in 2002, Sgarbi even announced that he intended to dedicate a monograph to the artist he so admires: “I am going to write a book on Cybei, of course it will not be box office but the people of Carrara will like it.” The volume was still in the works in 2008: “I am one of the greatest connoisseurs of Cybei, I also own some of his sculptures, and I am preparing a volume dedicated precisely to his artistic production,” unfortunately, however, we are still waiting. Also symptomatic was the placement that Sgarbi had reserved for the two Cybei, in his sumptuous Roman residence at Palazzo Pamphili on Via dell’Anima, kept in the most prestigious room of the house, “the most monumental place, but at the same time also the most protected, which is the bedroom of Innocent X,” where he kept “the things, I don’t know if more precious, but certainly of the highest absolute quality.”

Further proof of Sgarbi’s consideration for these two valuable portraits are also the long sequences dedicated in the aforementioned short film Belle di Notte. With background music by Gustav Mahler and seductive lighting and direction choices by Elisabetta Sgarbi, aimed at enhancing their preciousness, the two Cybei works were amply highlighted, while the better-known brother sang their praises: “In this room, in which I put these things so selected, there are these two formidable sculptures [ ] this extraordinarily realistic face and this formidable drapery, also with realistic elements like buttons, buttonholes, this formidable cockade, the cross of the Order of Lorraine...”. Yet it was right there, in his most secret room, in the works of one of his favorite artists, in the marbles among the finest in his collection, that something eluded Sgarbi himself.

Let us go back to the beginning of the story: the purchase of the two busts is not consequential to the passion for Cybei, but rather constitutes its premise. Sgarbi did not know the author and subject of the marbles when he came into possession of them, and having traced them back to the hand of the Carrarese, was due to a happy intuition of his, recalled in great detail in 2001: “I was then in Modena where, in the Biblioteca Estense, I found at the entrance, two sculptures that seemed to me to be by the same hand. I went up with the ladder: I saw the same buttonholes, the same buttons. I asked the director, Professor Milano, about those busts, and he said, Ah but they know each other: they are works by Antonio Cybei. Antonio Cybei was a distinguished sculptor who worked for the Este family in Modena...and who was the first director of the Academy of Carrara. And so from there I knew, also having the same base [ ] that they were indeed the work of Cybei.”

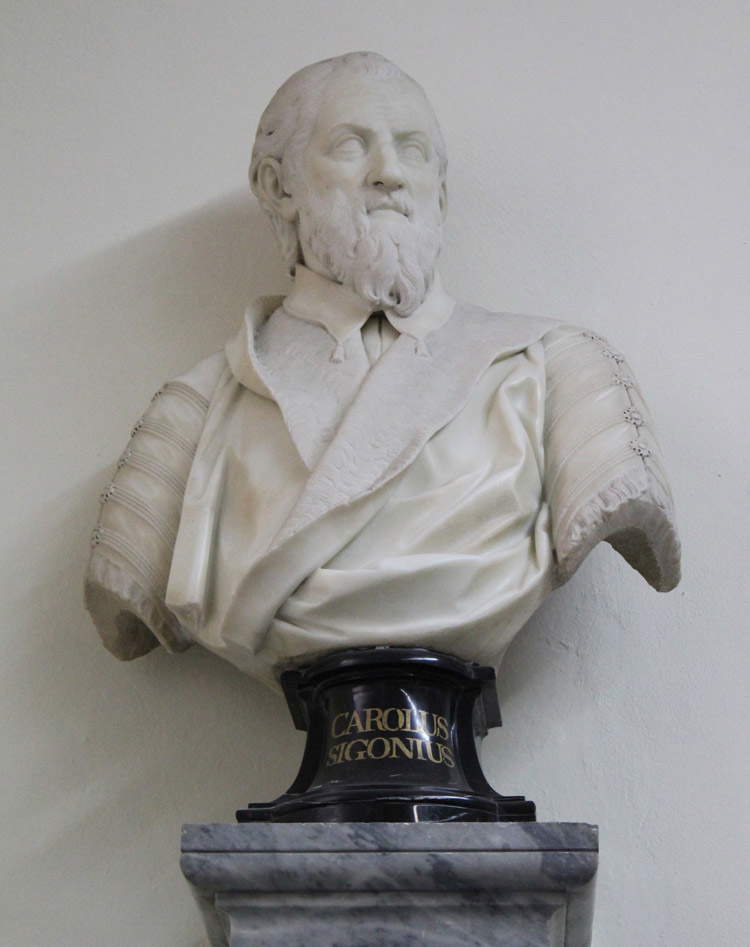

The two portrait busts noted by the critic in Modena are indeed documented works by Cybei, who executed them in 1774. Terracotta versions of them are also preserved in the deposits of the Estense Gallery and were exhibited in 1996 in the Sculptures at Court exhibition at the Rocca di Vignola. They represent two figures of great importance to Modenese culture, Ludovico Antonio Muratori and Carlo Sigonio, and as we shall see later, were executed only a couple of years after the busts in the Cavallini Sgarbi collection, to which they are evidently related.

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei, Portrait of Carlo Sigonio (1774; marble; Modena, Biblioteca Estense) |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei, Portrait of Ludovico Muratori (1774; marble; Modena, Biblioteca Estense) |

Clear, then, Sgarbi’s intuition in recognizing the hand of Cybei, less clear the mechanisms that led him to identify in the portraits these phantom Fratelli Masetti da Bagnano. Who were these people? And how come Cybei, who also left us a fairly complete list of his works, does not mention them? This is what Sgarbi recounted in 2001: “...going back to the family where they had been in Tuscany, which had a connection with the Modenese family. I also understood who the characters were: Masetti da Bagnano, two brothers, probably, from this rich family of merchants who later became aristocrats, counts, in Tuscany.” The road seems interesting, suggesting that there are documents proving these relationships, but the first catalog entry dedicated to the two Cybei, edited by Vittorio Sgarbi with the collaboration of Pietro di Natale, has little to add: “Reviewing the collecting history of the busts, Sgarbi also proposed that they identify portraits of two aristocrats, perhaps brothers, of the Masetti da Bagnano household, a wealthy family originally from Modena that gave rise to a branch established in Florence” (2008).

Nothing is given to us to know about the details of this “collecting affair,” and the only bibliography provided to support the hypothesis is a reference to Marquis Vittorio Spreti’s venerable (and glorious) Italian Historic-Nobiliary Encyclopedia. Logical (and rightful) to expect something more from the dedicated card in the very recent catalog of Le Stanze Segrete; nothing new instead, still the generic reference to the collecting history thanks to which “Sgarbi recognized the portraits of two aristocrats, perhaps brothers, of the Masetti da Bagnano household” (2016).

Who, then, are these Masetti brothers whose names are not even given? Are they personages so important as to have such sumptuous marble portraits, carved by a distinguished author, and of such rank as to display the Cross of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary?

Sgarbi’s writings and lectures do not comprehensively answer these questions, and the doubt that something is wrong, that a completely wrong path has been taken becomes very strong. It is not without hesitation that one disputes the one who had to declare, “Meanwhile, let it be clear, for me reason means that I am right” (2005), but this time Sgarbi has really taken a crab, and a big one.

In 1776 Cybei drew up a brief summary of his career, a “memorial” with a list of the main works he executed, the most illustrious patrons, and the fees he received; this precious document, fundamental for the reconstruction of Cybei’s artistic career, is preserved at the State Archives of Modena, and was unpublished until the publication of an essay by my signature, Dal Choro alla Bottega. Nuove acquisizioni su Giovanni Antonio Cybei(Commentari d’arte 14, Anno V 1999, Roma 2003), in which it was fully transcribed. Admittedly, this is not a magazine you would find on newsstands, but Commentari d’Arte is certainly one of the leading publications specific to the field, and it is a pity that someone like Sgarbi, so interested in Cybei, has never read it.

This memoir mentions a series of important busts executed by Cybei in the years immediately preceding its writing, roughly from 1770 to 1776; some of these works are well known, such as the portrait of Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine (in the Royal Palace of Pisa and the Victoria & Albert Museum in London) or of Empress Catherine II (Peterhof) and Duchess Maria Theresa (Reggio Emilia, Basilica della Ghiara), others, actually very few, are still missing from the roll call. Excluding a number of half-busts, among which the two alleged Masettis surely cannot be included, only the portrait of the Grand Duchess of Tuscany Maria Luisa of Bourbon (which we do not feel like considering...) and the busts of the two most important jurists of eighteenth-century Tuscany: Giovanni Bonaventura Neri Badia (judge, author and founder of the chair of international law at the University of Pisa) and his son Pompeo Neri, what we would now call a leading politician, with a career of more than a decade in the grand ducal administration, culminating in his appointment in 1770 as President of the Council of State, roughly the equivalent of a current prime minister, second only to Grand Duke Pietro Leopoldo himself.

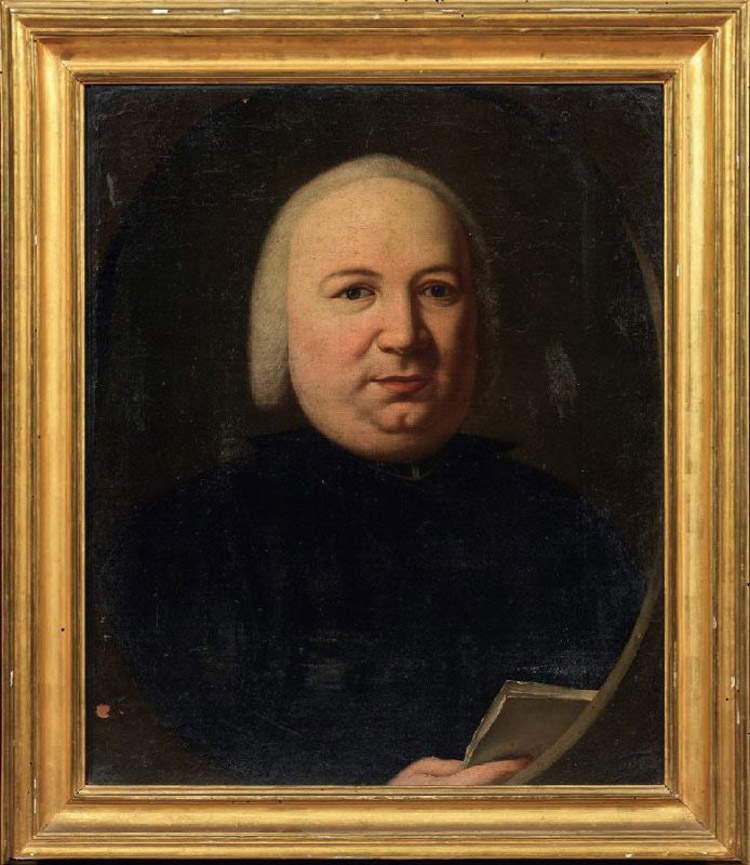

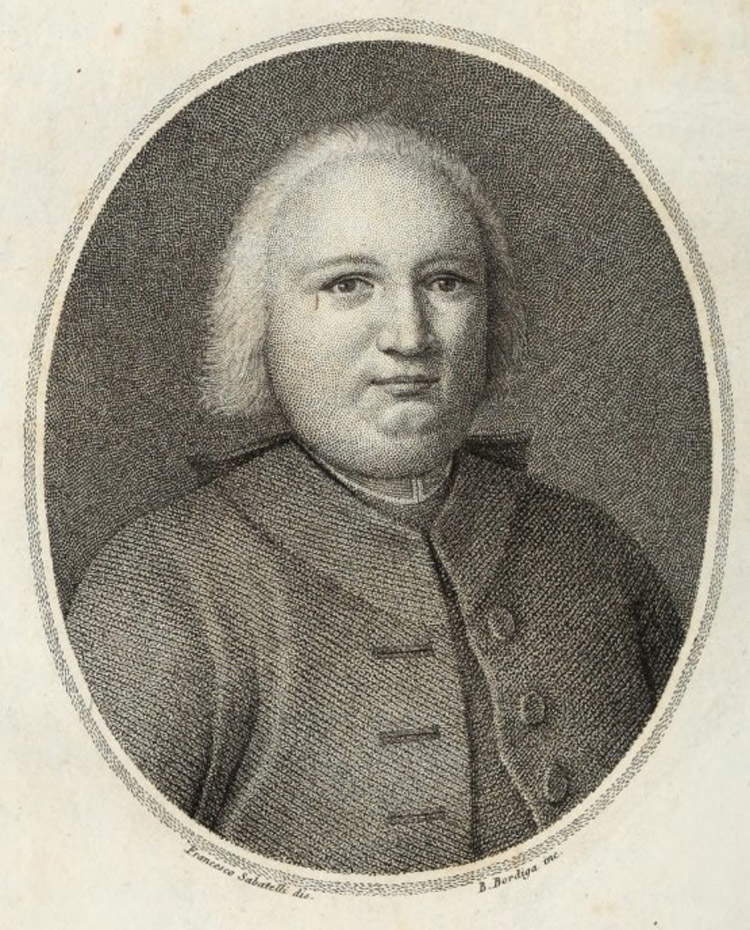

“To honor him [Cybei] concurred also His Excellency Mr. President Pompeo Neri, wanting by his own hand his own Portrait, and that of his Father for which, besides filling him with a thousand attentions he made him a present in zecchini gigliati n°100, excusing himself by saying, that no he was the Grand Duke” (1776). The circle is tightening, the possibility that the two busts are precisely those mentioned by Cybei must be taken into consideration, and a quick and intuitive comparison of the physiognomy of the face of a portrait of Pompeo Neri (e.g. the printed one by Francesco Sabatelli and Benedetto Bordiga, or the oil one recently passed on the antiquarian market in Florence) with the busts of the “Masetti” is enough to move from hypothesis to certainty: it does not need an expert eye to recognize in one of the two marbles the exact correspondence with Neri’s features: the last “secret” of Sgarbi’s rooms is revealed.

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei, Portrait of Giovanni Bonaventura Neri Badia (1772; marble, 74 x 70 x 30 cm; Ro Ferrarese, Cavallini Sgarbi Collection) |

|

| Giovanni Antonio Cybei, Portrait of Pompeo N eri (1772; marble, 79 x 70 x 35 cm; Ro Ferrarese, Cavallini Sgarbi Collection) |

|

| 18th-century Sienese School, Portrait of Pompeo Neri (second half of the 18th century; oil on canvas, 58.8 x 48.5 cm; Private Collection) |

|

| Francesco Sabatelli, Benedetto Bordiga, Portrait of Pompeo Neri (post 1768 - ante 1829; etching print, 7.1 x 8.6 cm; Monza, Civica Raccolta di Incisioni Serrone Villa Reale) |

|

| Castelfiorentino plaque |

We could also stop here, so obvious is the identity in the somatic features, but it would seem unserious, ultimately rude, not to go deeper into the subject. Let us return to the famous “collecting affair” at the basis of Sgarbi’s deductions; not even accurate and lengthy archival research is needed, but reading a plaque placed on the public street, in the facade of Pompeo Neri’s palace in Castelfiorentino, is enough to get a first answer: “This house inhabited and with his name made most honored Pompeo Neri Badia author in the councils of state of civil reforms in times of privileges proponent of economic freedom when the state was all the citizen nothing. Pier Pompeo Masetti sole survivor of the Neri Badia family on May 28, 1882 commemorating....” Yes, you read that right, just one sentence is enough to clarify the relationship between the Masettis and Pompeo Neri’s family; the idea that the collecting history could lead back to the identity of the retracted was right, the unfolding of the theme well short of thoroughness.

And that much ostentatious Cross of St. Stephen of Hungary on the bust that we now know to be Pompeo Neri’s? It is not exactly commonplace: the order had been established in 1764 by Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, and was reserved for particularly prominent personalities of the Holy Roman Empire. From its founding to 1792, only eight foreigners were awarded the knight’s cross. Shouldn’t it have sounded like a wake-up call that one of these obscure Masetti brothers had had access to such a high honor? When in doubt, there are also printed lists of knights awarded the order, and lo and behold, who do we find among them? Our very own Pompeo Neri.

The news was not one that went unnoticed at the time, this, for example, was written in the Nov. 25, 1769, Tuscan Gazette: “The Emperor has in the past few days elevated to the dignity of Grand Cross of the Royal Order of St. Stephen the Count of Coblenz [Karl Von Coblenz], Knight of the Golden Fleece, and Minister Plenipotentiary in the Netherlands: And has likewise Sovereign Majesty appointed Mr. Abbot Pompeo Neri, First Secretary of State of the Archduke, Grand Duke of Tuscany, a Knight of the said Order.”

Our good Pompeo, evidently very proud of the honor, did not fail to flaunt its symbol in plain view, and in the eighteenth century these were things that were written about in the “newspapers”: Pisa, December 6, 1769 - His Excellency Mr. President Pompeo Neri having been decorated by Her Majesty the Queen Empress, of the Cross of Knight of the Order of Saint Stephen of Hungary, began since last week to wear its uniform, which he received at the hands of our Royal Grand-Duke..."

Everything, in short, comes together, from the Cross of Saint Stephen to the collecting affair, from Cybei’s direct testimony to the full identity with Pompeo Neri’s facial features, and it is very suggestive to read the description of the same left to us by Angelo Ridolfi in his “Eulogy of Pompeo Neri” observing his portrait: “He was of a most suave character: grave and eloquent in his speech: always equal to himself: firm and constant in his well-considered divisions [ ] The playfulness of his soul shone through his lively eyes.”

On the other hand, no portrait of Giovanni Bonaventura Neri Badia, Pompeo’s father, is known at present, although already the common affair should support the recognition. A great difference in the hairstyles and clothing of the two portraits, however, jumps out at us: for the former of the two busts, parallels can be drawn with the fashion of Gian Gastone de’ Medici’s time, as appears, for example, in Franz Ferdinand Richter’s portrait in the Pitti Palace, in which the Grand Duke presents a sumptuous lace jabot and an imposing hairstyle made of long ringlets with central parting, elements that we find exactly in the portrait of Neri Badia. The portrait of Pompeo Neri, on the other hand, presents him with a Louis XV-style wig, gathered and probably powdered, similar to the one worn by Grand Duke Francis Stephen of Lorraine in the portrait (as Emperor Francis I) by Pompeo Batoni preserved at Schönbrunn.

|

| Detail of the jabot by Giovanni Bonaventura Neri Badia |

This brief excursus into eighteenth-century fashion just to point out how the two figures belong to different generations, as a father and son for example, certainly not as two brothers, another detail that was not to escape the critics.

Having now unveiled every “secret” that escaped Sgarbi’s eye, all that remains is to close with the dating of the two works, which Cybei’s chronology suggests were executed in 1772, at the height of Pompeo Neri’s “political” career, and of the author’s artistic one. We sneak out of the Secret Rooms, amused at having unveiled a secret that had eluded Sgarbi himself, despite having it right under his nose, among his most cherished possessions, and close by wishing that in the near future, perhaps on the next leg of the “tour,” the two Cybei busts will be presented with updated hangtags. They deserve it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.