The secret pleasure of looking: voyeurism, between art and forbidden books

Pleasure is a game of shadows and reflections that has always climbed into the impalpable fabrics of art, enveloping each work in veils of mystery and desire in which the gaze sneaks furtively from a curtain raised with studied lightness, from a small peephole or from behind a hedge. The game of voyeurism is a subtle art, a power that feeds on secrets and stolen visions in which the tension between seeing and being seen, between hiding and revealing, lends a depth that is not only carnal but exquisitely existential. It was probably this exciting paraphilia that guided, in 1859, Jean-Léon Gérôme in the creation of the canvas The King Candaule, which depicts an event based on an episode that occurred during the 8th century B.C. and narrated by Herodotus.

The king of Lydia, Candaule, was so captivated by the beauty of his own bride that he wanted to show her off to his trusted guard Gige, son of Dascilo. “Gige, I think you do not believe me when I tell you of my wife’s beauty: indeed, ears are less reliable witnesses than eyes. Well, see to it that you see her naked,” the ruler urged him. The guard promptly refused, fearing that some misfortune might ensue, but in the end Candaule convinced him by asserting that his bride would never find out. Jean-Léon Gérôme painted exactly that exquisitely sensual moment in which the beautiful woman is intent on removing her robes, gently slipping them off and laying them on her right, while the guard awkwardly tries to hide behind the door of the bridal chamber. But the intense interplay of glances fails because the artist, as the story itself intended, depicted the enchanting creature with the sidereal skin at the very moment she turns her gaze to the man hidden in the shadows. A depiction, this one, that shifted the focus from the mere vanity of the king, severely criticized by Herodotus, to go in search of a pleasure that crept between the boundaries of desire making the viewer the true voyeur.

It is precisely while the gaze is lost and captured by the textures of a canvas, or while the fingertips glide along the geographies of a book creating a mute dialogue between skin and paper, between eye and colors, that the true act of abandonment is consummated: a doubling of desire, a spiral in which art and literature offer themselves as double mirrors, places where the gaze plunges into secret contemplation and is reflected in an act of deep and silent perversion.

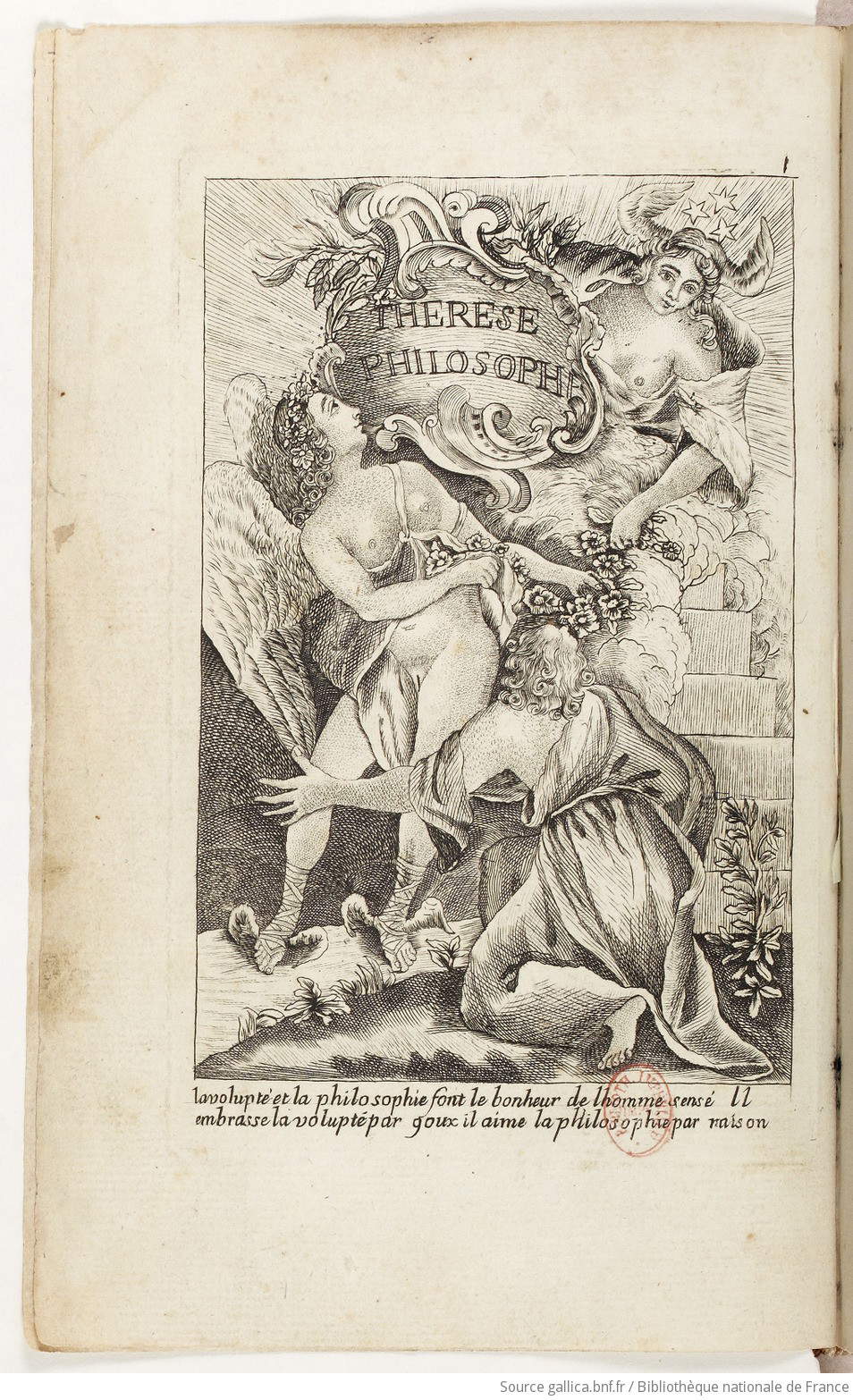

Figurative art, throughout the course of history, has often given light to visual dynamics of seduction and hidden gazes; one need only think, for example, of the story of Artemis told by Callimachus, Ovid and Pausanias and portrayed with vivid pictorially by many artists, including Francesco Mazzola, known as Parmigianino, who in his fresco on the ground floor of the Sanvitale fortress in Fontanellato showed the moment when the seductive virgin discovers the hunter who was spying on her. But it was literature, particularly during the Ancien Régime in France, that pushed the boundaries of the morally acceptable as demonstrated by the book Thérèse philosophe. First published probably around 1748, this clandestine text became one of the most popular in France, ranking 15th among the banned “best sellers” compiled by STN, the Société Typographique de Neuchâtel, which was one of the most important clandestine publishing networks in 18th-century Europe. But the STN’s success stemmed not only from its scandalous content, but also from an innovative publishing strategy: it printed and distributed on demand, adapting to market needs and maintaining a network of couriers and intermediaries to evade seizures. In addition, the printing company kept a detailed archive of correspondence with its customers, now a valuable historical source for understanding the clandestine book market in the 18th century.

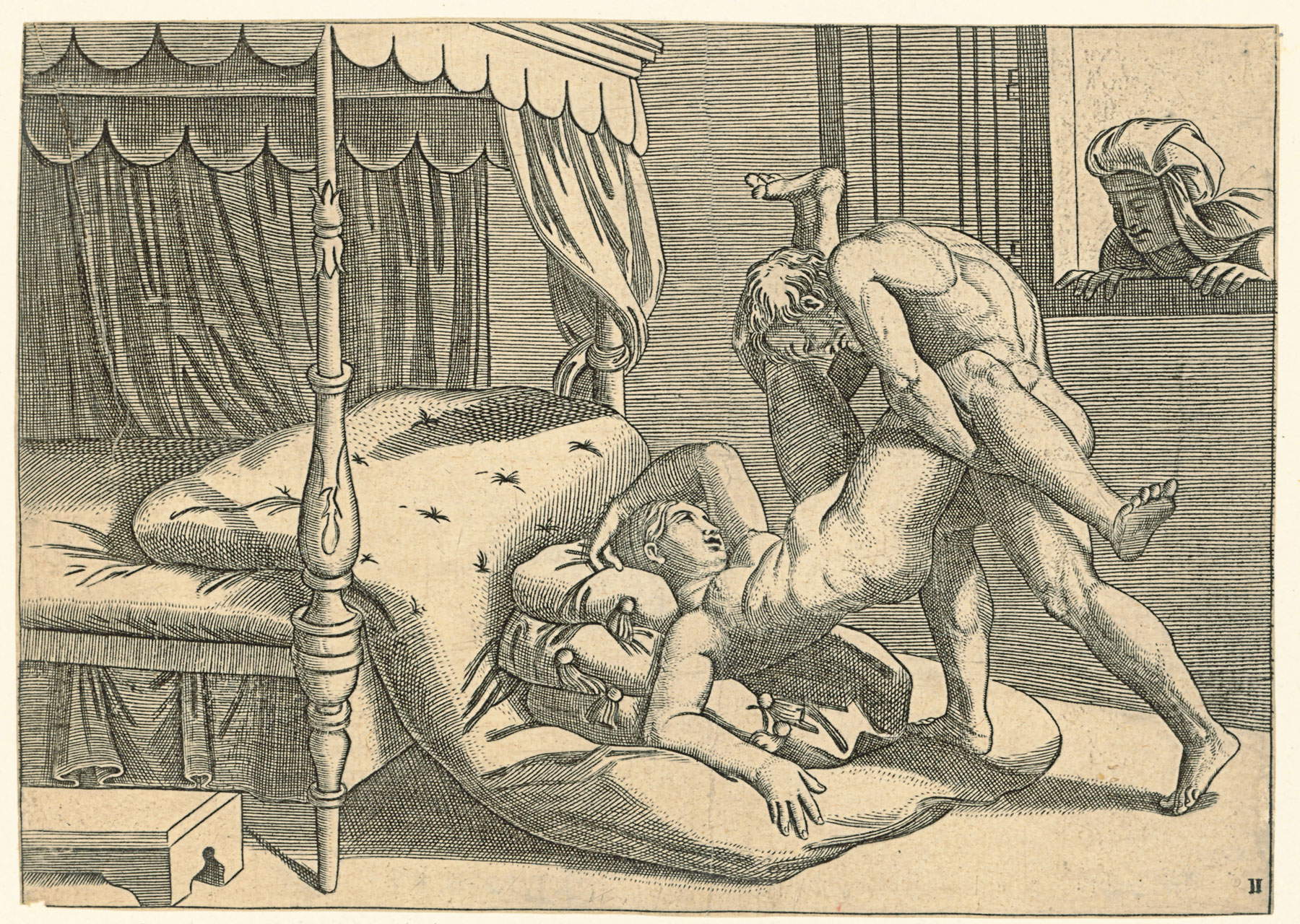

It would, however, be entirely misleading to imagine the censorship of books and pamphlets through spectacular burnings, which only enthralled the public and increased the attractiveness of the most licentious readings. Instead of physically destroying banned volumes, the authorities preferred to seize them and prosecute those who traded in them or encouraged their dissemination. It was the latter, more than the authors themselves, who suffered the severest consequences of attempts to suppress the circulation of ideas deemed dangerous, despite the fact that works of an erotic nature had existed for centuries. Suffice it to recall how Ovid celebrated the glories of carnal love, and how, in the sixteenth century, the poet Pietro Aretino inaugurated new paradigms with the introduction of the use of turpiloquy, the description of the sixteen positions, and the use of the female narrator in his Lustful Sonnets and Ragionamenti.

It was in this cultural humus that French libertine tales developed, populated by characters spying on each other through slits and curtains, while the reader became part of this voyeuristic game, invited to observe in a discreet but participatory manner. The illustrations emphasized this dimension, often depicting couples in sexual acts or engaged in autoerotic acts, in an implicit dialogue between text and images. Even Rousseau, author of works such as the Œuvres, joked that such books should be read “with one hand.” In the eighteenth century, in fact, masturbation was thought to cause a very numerous range of diseases, from emaciation to blindness, but stories such as La Putain errant or La Fille joie proved the audience otherwise. Thérèse philosophe, however, was not just a licentious tale, but a vivid portrayal of the spirit of the Enlightenment, which aimed to subvert moral and religious conventions by fusing eros and philosophical thought.

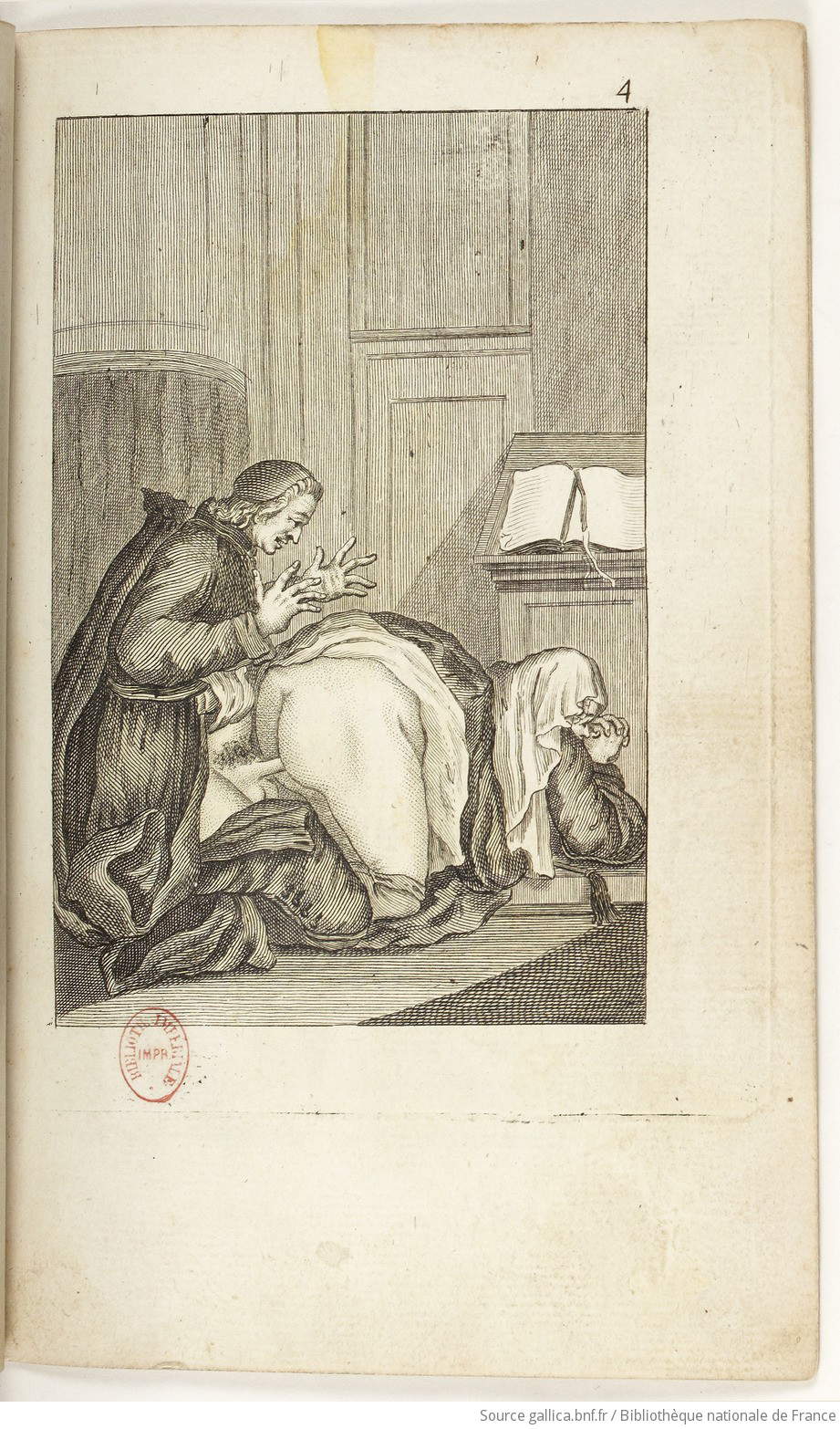

The protagonist Thérèse narrates her journey of sexual formation through episodes of voyeurism, such as the one in which she observes Father Dirrag as, with cunning impiety, he induces mademoiselle Éradice to confuse the physical pleasure he brings her with a mystical ecstasy. This interweaving of the sacred and the profane not only breaks the boundaries of the Cartesian dichotomy between mind and body, but reveals a veiled critique of ecclesiastical institutions, reinforced by the illustrations depicting the nun, oblivious and lost in her prayers, as she indulges in intercourse.

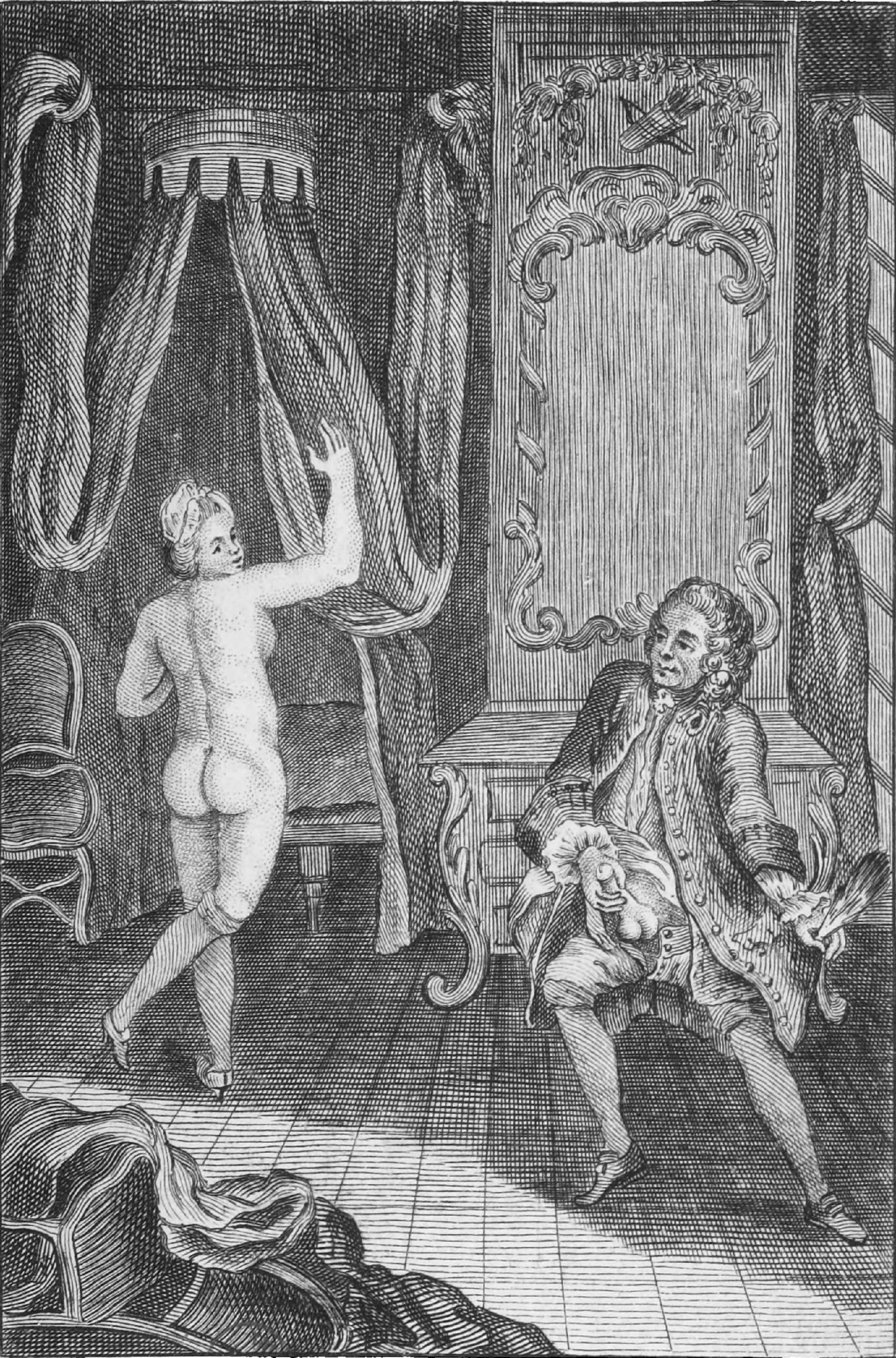

In this libertine literary universe there is no room forromantic love; in fact, emotional life in the eighteenth century was deeply marked by a dramatic demographic context: high infant and maternal mortality, together with the absence of the possibility of divorce, meant that marriages often lasted only a short time (an average of 15 years) because of the woman’s premature death. The terror of pregnancy, then, with the lethal dangers it entailed afflicted women of the time, as is evident in the story itself, in which Thérèse decides to forgo full relationships to avoid such risks. However, the story culminates with the protagonist succumbing to a wily count, who challenges her with a devious wager: if Thérèse managed to spend two weeks in his library, exploring erotic volumes and admiring lewd paintings without giving in to the desire to practice autoeroticism, the entire library would be his; if not, the count would own it. Thérèse lost herself in a whirlwind of sexual fantasies as she consulted STN’s licentious books such asHistoire de Dom B... andHistoire de la Tortiniere Carmélite, and contemplates erotic paintings such as The Feast of Priapus andThe Loves of Mars and Venus while, overcome by her urges, she slips her hand down her thigh, the count, who had been spying on her constantly, bursts furiously into the room to claim his prize by practicing coitus interruptus.

Despite the ending, which seems to portray the narrator as a mere sexual object, Thérèse Philosophe draws from the entire repertoire of libertine theses, transforming herself into a philosopher who openly challenges the dominant values of the Ancien Régime by drawing the reader into an intellectual voyeurism and inviting him or her to play with the idea of an alternative social order, a territory in which all experimentation becomes possible.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.