The sea voyage according to Lucio Fontana: the ceramic panels of Conte Grande

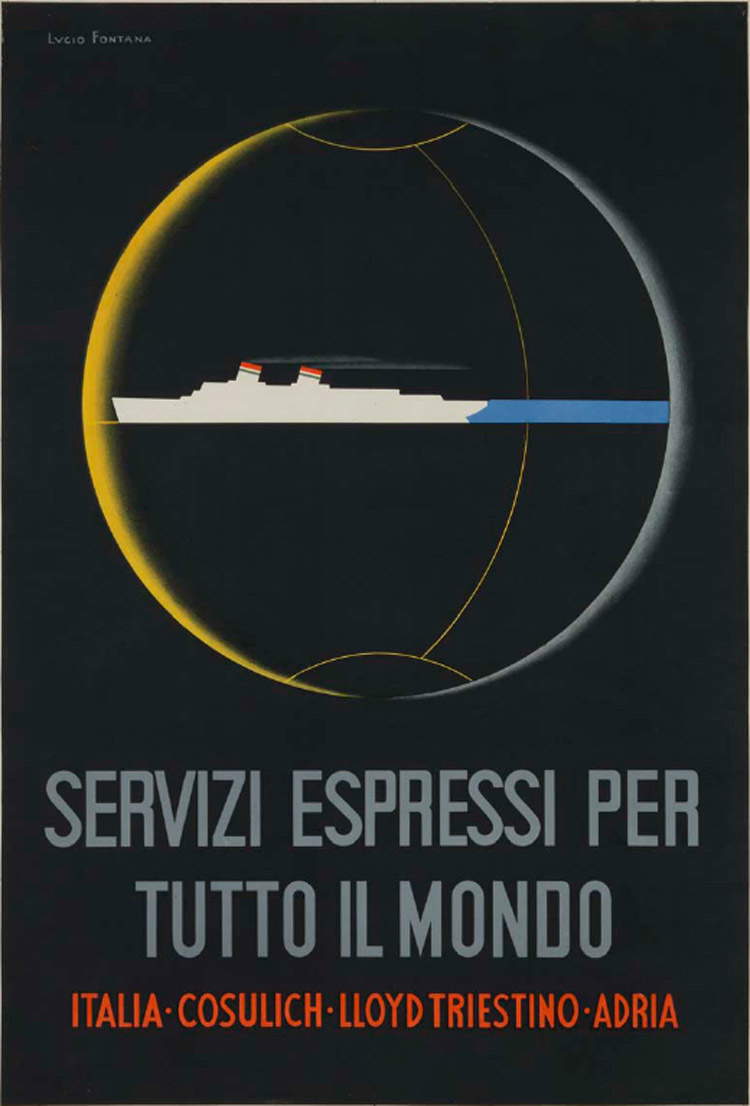

It was 1935 when a then 36-year-old Lucio Fontana (Rosario, 1899 Comabbio, 1968) participated in a competition announced by Italy’s most important shipping group,Italia Flotte Riunite, which brought together some of the country’s leading companies under a single umbrella. The great Argentine-born artist had recently taken up with the famous Galleria “Il Milione” in Milan and had become acquainted with the abstractionist circles operating in the Lombard capital: the geometric abstractionism of Mario Radice, the lyrical abstractionism of Osvaldo Licini, the suggestions that the artists of “Il Milione” drew from the French movements, in particular from the Abstraction-Création association, which Fontana moreover joined precisely in 1935, all contributed to create a particularly fertile and suggestive environment, which ended up being resonant on the manifesto that Fontana was to create for the competition. The shipping group, in fact, was looking for a new advertising poster that would advertise its passenger shipping services, at a time when ships were precisely the main means of transportation of choice for long voyages.

The poster was appreciated because of its immediacy and communicative ability through which, with a formidable synthesis, Fontana succeeded in conveying the message that the group intended to get across to potential customers. The reasons with which the jury awarded the prize to Fontana, which also included a quick description of the work, were published in the periodical Sul mare, the travel magazine of Lloyd Triestino and Cosulich (two of the largest companies of the time: Cosulich, moreover, had become part of the Flotte Riunite, but maintained a certain autonomy until 1936), in an article entitled The Success of the Great National Competition: “the prize-winning sign, of exquisite execution, succeeds in summarizing, in an irreducible economy of lines, the themes imposed by the call for entries, producing an admirable work of art as well as effectively advertising: a globe hinted at in its essential elements, circumference and some trace of parallels and meridians, and, on the equatorial diameter, the fleeting vision of a ship, sprung up like a ray of sunshine.” Economy of colors, as well as of lines: white, black and primary colors, hues that might palpate a direct reference to Abstraction-Création (one of the two founders, Georges Vantongerloo, was also one of the founders of the De Stijl group), are the only ones that characterize the poster’s elements, from the globe (a simple circle with shaded contours, three arcs to form the polar circles and a meridian and a horizontal line for the Equator) to the outline of the ship via the claim “Express Services for the Whole World” and the names of the companies, and they help to grant the poster thatessentiality deemed so effective by the jury and that ensured the work such popularity that it continued to be reproduced, albeit with some modifications, until the 1950s.

|

| Lucio Fontana, Express Services for the Whole World (1935; print on paper, 100 x 69 cm; reproduced in several copies) |

The work allowed Fontana to circulate his name among shipping companies: the poster, in fact, was but the first of several works the artist produced for shipping companies. Two years later, for example, he was commissioned to make four reliefs for the Floating Pavilion that the Italian shipping companies were presenting at the International Exhibition in Paris. Meanwhile, Fontana had met, just in 1935, one of the leading exponents of Futurism, the Ligurian Tullio Mazzotti, whom Marinetti had nicknamed Tullio d’Albisola (Albisola Superiore, 1899 Albissola Marina, 1971): he had been the intermediary of the anti-fascist art critic Edoardo Persico, during a meeting in Genoa. It was thanks to this acquaintance that Fontana decided to deepen his relationship with ceramics and move to Albissola Marina, where he began a fruitful production of ceramics, which he never abandoned for the rest of his career, so much so that in the 1950s he decided to locate a studio, located in the old Pozzo Garitta square, in the town of Savona. Fontana, as early as 1937, had adhered to the Futurist Ceramics Manifesto and, in the second half of the 1930s, began to collaborate actively with the Mazzotti family, owners of one of Albissola’s historic ceramic factories. And it was from the Mazzotti’s kilns that the five ceramic panels destined for the “Conte Grande,” an ocean liner built for Lloyd Sabaudo and launched in 1927, came out: it served the Genoa-New York line, but was later also destined for voyages to South America, and it was in Rio de Janeiro, in 1940, that it was requisitioned by the Brazilian government and handed over to the U.S. Navy, which converted it into a troop ship. Handed back to Italy in 1947, the “Conte Grande,” chartered by the Italia Company, returned to its role as a passenger ship.

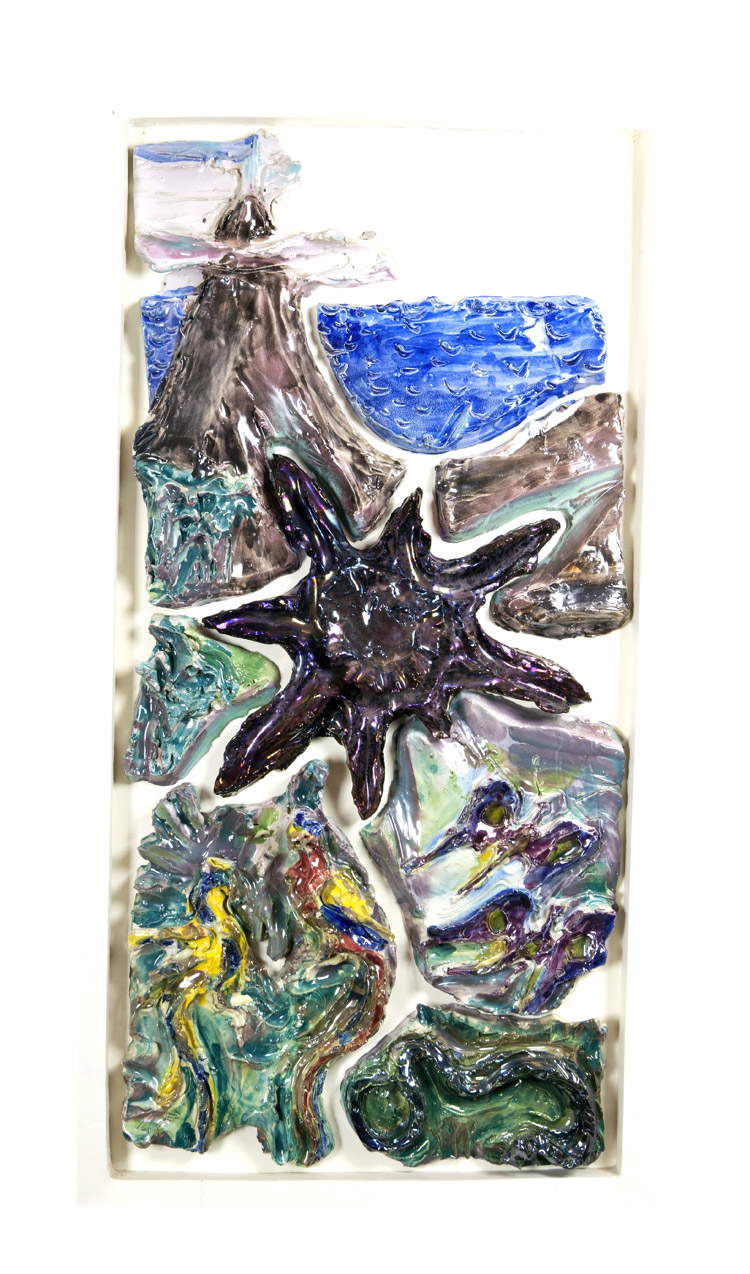

The first voyage of the modernized liner took place on July 15, 1949, from Genoa to Buenos Aires (curiously enough, a city where Fontana, who was born in Argentina itself, had repaired when Italy took part in World War II, and remained there until 1948). A few months earlier, the sculptor had been commissioned to make ceramic panels that were to decorate the lobby of one of the galleries of the “Conte Grande,” the first-class one, and which were to have, as their subject, sea travel. There were five in total, and they represented the Equator (the only one lost), the Mediterranean, Spain, Brazil, and the Knights of the Apocalypse. The intent was to ideally link the stages touched by the “Conte Grande” during its ocean crossings, and Fontana ’s works were part of a wide-ranging artistic project, the history of which is summarized in Cecilia Chilosi ’s essay entitled Mediterraneo, Spain, Brazil, The Knights of the Apocalypse: the four ceramic panels aboard the Conte Grande and Fontana’s contribution to the architecture of Nave, the only essay on the work created by the artist for the liner. Italy, after the war, needed to reconstitute a “fleet worthy of past prestige”: the task fell to Finmare, the maritime finance company founded in 1936, which, as part of a state-led project, supported with its own means the activities of the main shipping companies (including, again, Italy and Lloyd Triestino), in which it had taken a majority shareholding. The reconstitution of a modern fleet also passed through the refitting of ship fittings. An important role was to be played byart: indeed, the ships would accommodate works by the most celebrated masters of the time, in order to create an “atmosphere of elegant worldliness,” which was considered particularly suitable for the modern, educated, arts-loving customer. The applied arts, such as ceramics, were considered an integral part of this project.

|

| Lucio Fontana, The four panels of the “Conte Grande” at MuDA in Albissola Marina. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| Lucio Fontana, The Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1949; glazed terracotta with third-fire lustres, 132 x 77 cm; Albissola Marina, MuDA - Exhibition Center). Ph. Credit MuDA Albissola Marina. |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Spain (1949; glazed terracotta with third-fire lustres, 132 x 77 cm; Albissola Marina, MuDA - Centro Espositivo). Ph. Credit MuDA Albissola Marina. |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Mediterraneo (1949; glazed terracotta with third-fire lustres, 132 x 77 cm; Albissola Marina, MuDA - Centro Espositivo). Ph. Credit MuDA Albissola Marina. |

|

| Lucio Fontana, Brazil (1949; glazed terracotta with third-fire lustres, 132 x 77 cm; Albissola Marina, MuDA - Centro Espositivo). Ph. Credit MuDA Albissola Marina. |

|

| The display of Lucio Fontana’s panels at the MuDA in Albissola Marina (in the foreground, also by Lucio Fontana, note the White Lady). Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

When Lucio Fontana’s panels came out of the Mazzotti’s GMA manufacture in Albissola and were installed on the “Conte Grande,” critics showed considerable appreciation, as can be gleaned from a few lines published, in 1950, in Domus magazine: “the panels by Lucio Fontana, fired in the kilns of Tullio Mazzotti, a Ligurian ceramist from Albisola near Savona, poetically symbolize, in the allusive modern plastic and in the colors of the stupendous enamels, the line of the sun and the sea, Mediterranean and Atlantic that the Conte Grande travels.” The cycle is meant to symbolize the sea voyage and can be read starting with the Horsemen of the Apocalypse, a theme that recurs other times in Fontana’s postwar production, a probable allusion to the upheavals that the war had caused, and that we wanted to leave behind. The one with the horsemen is the only panel that bears the artist’s signature in full (we see it in the lower left corner): the others are more simply initialed. The current display of the four surviving panels, kept at the exhibition center of the new MuDA (Museo Diffuso Albissola) in Albissola Marina, presents us with Spain as the first stop on the itinerary: a common feature of the entire cycle of the “Conte Grande” is to evoke the theme of each panel through characterizing elements. The one from Spain, for example, presents in the center of the composition a bullfighter holding a capote, the large cloth used to tire out the bull in one of the bullfighting stages (as distinct from the muleta, the smaller one, which the matador holds in one hand and uses in the finale), and, next to him, a large black bull that is charging him. The Mediterranean panel is distinguished by its warm hues and symbols that evoke the ancient cultures that flourished along its shores: in the center is a large sun illuminating the sea (also common to Spain and Brazil), all around appear centaurs, a jellyfish head, and columns with Ionic capitals. The last leg of the journey, Brazil, features a large sun in the center, in darker hues, illuminating a landscape in shades of blue and green: we see in the background the vast expanse of theocean surmounted by Sugarloaf Mountain and, in the lower register, animals typical of Brazil: colorful parrots and ananaconda crawling through the vegetation.

These splendid ceramics are distinguished by their great plastic force, typical of this phase of Lucio Fontana’s production, which at the time was in the midst of the path that would lead him toward the poetics of Spatialism that would characterize the last part of his career and, at the same time, represent its most revolutionary and original outcome (such as to guarantee him a prominent place in the history of art): forms that writhe in swirls that evokeBaroque aesthetics, that acquire such vigor that the panels take on the character of sculptures (Fontana claimed to be a sculptor rather than a ceramist), that breathe life into the material, and that with their contrasts between solids and voids somewhat anticipate the spatial concepts that Fontana began in that very same 1949. The great brilliance of the colors and their tendency to iridescence are due to the lustro technique with which Fontana finished the panels: the ceramic, already glazed, is fired for a third time, but at lower temperatures and with the addition of a special impasto, based on metallic salts, so as to guarantee the work thus transformed iridescent effects that intend to imitate the effect of metals and precious stones.

In 1962, the year in which the “Conte Grande” was sent for demolition, almost all the furnishings were sold at auction by Finarte: some works, however, remained in the warehouses of the Italia company. Among the latter were the panels by Fontana. Of the one depicting the Equator, as anticipated, the fate is unknown. The others, however, resurfaced in the 1990s and, after Cecilia Chilosi’s report dating back to 1995, were donated, in 1999, to the City of Albissola Marina. They were then sent to Faenza where they underwent restoration at the Laboratory of the International Museum of Ceramics, then were exhibited for the first time, also in that same year, at the exhibition that the city of Milan dedicated to the centenary of Lucio Fontana’s birth. When they returned, they were destined for the Museum of Contemporary Art in Albissola Marina. Temporarily exhibited at the Fornace Alba Docilia in 2010, at the time of the reorganization of the Ligurian town’s civic museums, since 2014 they have been conserved, as mentioned above, at the MuDA exhibition center in Albissola Marina, where they have found a worthy and prestigious collocation, within a setting that succeeds in fully enhancing them: it is here that the public can now admire these four works, witnesses to one of the most fervent seasons of our art history and an important stage in the artistic career of one of the great names of the twentieth century.

Reference bibliography

- Paola Valenti, Lucio Fontana: in dialogue with space: environmental works and architectural collaborations (1964-1968), De Ferrari, 2009

- Cecilia Chilosi, Mediterranean, Spain, Brazil, The Knights of the Apocalypse: the four ceramic panels aboard the Conte Grande and Fontana’s contribution to the architecture of Nave in Elisa Coppola (ed.), Six wonderful days: an invitation to travel on the great Italian ships, exhibition catalog (Genoa, Museo dell’Accademia Ligustica, December 13, 2002 - February 16, 2003), Tormena, 2002

- Sarah Whitfield, Lucio Fontana, University of California Press, 2000

- Paolo Campiglio (ed.), Lucio Fontana: letters 1919-1968, Skira, 1999

- Cecilia Chilosi, Liliana Ughetto, La Ceramica del Novecento in Liguria, Carige, 1995

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.