The scrolls and codices of St. Scholastica, the tale of a thousand-year history

A library with a thousand-year history, and with materials that have spanned untold centuries of history. This is how one could describe the State Library of the National Monument of St. Scholastica, which owes its origins to St. Benedict: it is in fact the library of the Monastery of St. Scholastica in Subiaco, one of the twelve monasteries that were founded near the town in the Aniene Valley by St. Benedict himself. The library was enriched especially from the 12th century onward, and today it preserves an important Monastic Archive, where it is possible to find the significant parchment collection that consists of about 15,000 documents and 3,883 parchments (including pontifical documents, royal documents, notarial acts, and much more), ranging from the 12th to the 18th century and concerning the temporal and spiritual administration of the abbey territory. There are, for example, documents dealing with purchases and sales, resolutions of disputes, court judgments, and then again sheets with contracts, inventories, land registries, land, pardons, and much more: the whole history of the abbey written on paper.

This is largely unpublished material since few documents in the archive have been published and transcribed. The cataloguing of this material is due to Leone Allodi (Parma, 1841 - Subiaco, 1914), who was superintendent of the monasteries of Subiaco after the Unification of Italy: in fact, the young state, in 1866, established the suppression of the monastic orders which, after the annexation of the territories of the former Papal State, also touched Rome and its surroundings from 1873. The Sublacensis monasteries, like other monasteries scattered throughout Italy, were thus declared national monuments: the Minister of Public Instruction, in 1874, intended to propose the monk Luigi Tosti as superintendent, but the appointment in the end, by decree of April 25, 1874, fell to Leone Allodi, who immediately worked to have the parts of the monastery in need of intervention restored and, above all, took steps to reorganize the library and the archives: the catalog of the documents of St. Scholastica still in use today is due to his action. Always Allodi, moreover, described all the documents and incunabula in the archive and library, which is why his work is still very valuable for studying what is preserved within the walls of the institute.

The parchments of the

The parchments of the The parchments of the Monastic

The parchments of the MonasticIn addition, Allodi was responsible for cataloging the codices in the ancient fund of St. Scholastica, counting 436 items, a number that has also been confirmed by recent cataloging, and within which are found both manuscripts from St. Scholastica and manuscripts from the Sacro Speco of Subiaco: the small number compared to the thousands that the library once preserved attests to the amount of dispersions that over the centuries have impoverished the collection. However, even if the surviving material is a fraction of what was once in the library, it still constitutes a very useful basis for understanding what life was like in ancient times in the monastery of St. Scholastica. In particular, the texts preserved by the codices that have come down to us, has written scholar Luchina Branciani, who has long dealt with the funds of the Sublacensis monasteries, “concern the disciplines underlying the formation of the monk and reflect the lively of culture circulating in monastic circles through the centuries, ranging from normative texts such as the Rule, to the Bible, its exegesis, the Fathers, ascetics, hagiography, liturgy, music, law, and scientific literature.”

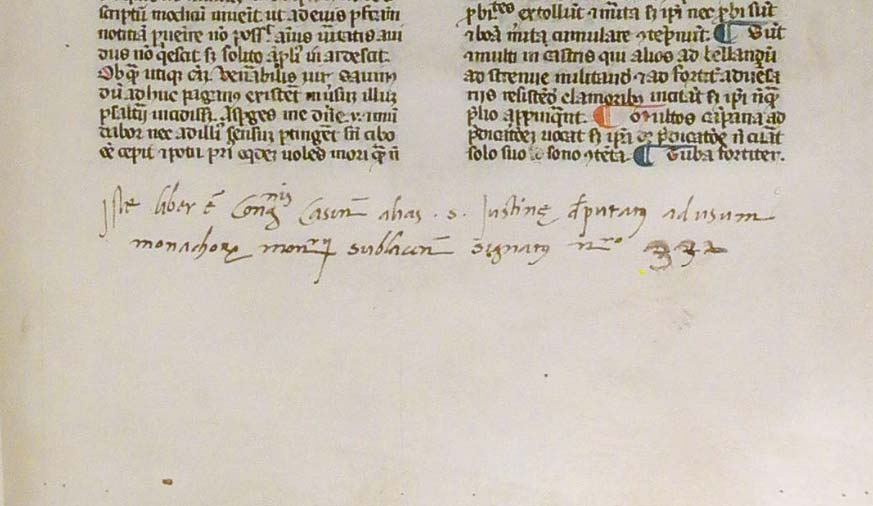

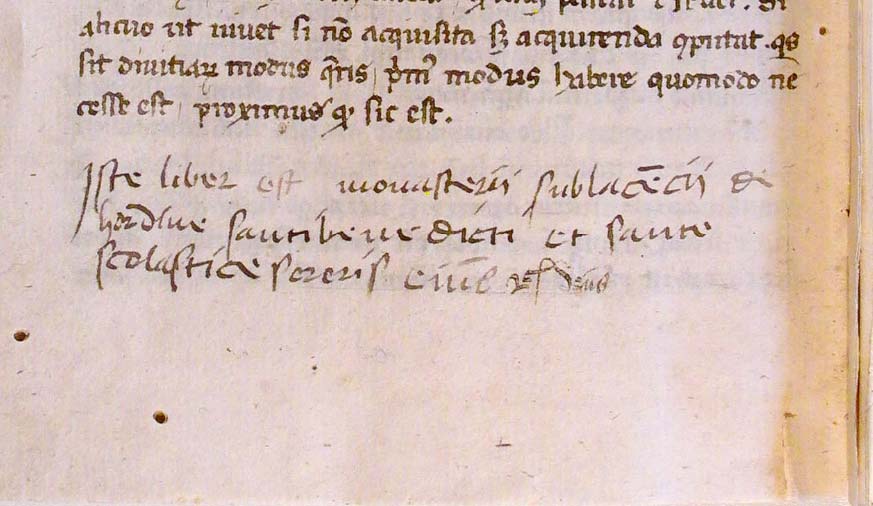

Moreover, from the names of the copyists we find on the codices produced in the scriptoria of the Sublacensis monasteries, we get the news of many foreign presences: in Subiaco there were in fact Spanish, French, German, Austrian, Polish, and Dutch monks who in signing themselves also inserted their place of origin. We also know, again from this material, that the first complete cataloguing of the book and documentary holdings of the monasteries of Subiaco dates back to the sixteenth century: the credit for this operation is due to the monk Guglielmo Capisacchi da Narni, who was present in the monastery of St. Scholastica from 1527. His work of cataloguing is evidenced moreover by the markings and possession notes that he himself drew by hand on the codices to report their ownership. Some possession notes (such as the one affixed in manuscript 217) attest to the change of location between the library of the Sacro Speco and that of St. Scholastica, and show how always in the sixteenth century the two libraries were united. And always the sixteenth-century markings show a precise intention of cataloguing by the fact that the objects are numbered (something that is not recorded in the possession notes of the previous century): for example, on manuscript 40 we note the inscription Est sacri monasterii Sublacensis signatus number 332, with the handwriting of Capisacchi. Two notes could also be found on the same manuscript: in fact, manuscript 40 also bears the note Iste liber est congregationis Casinensis alias sanctae Iustinae, deputatus ad usum monachorum monasterii Sublacensis signatus numero 332, written in the first half of the 16th century.

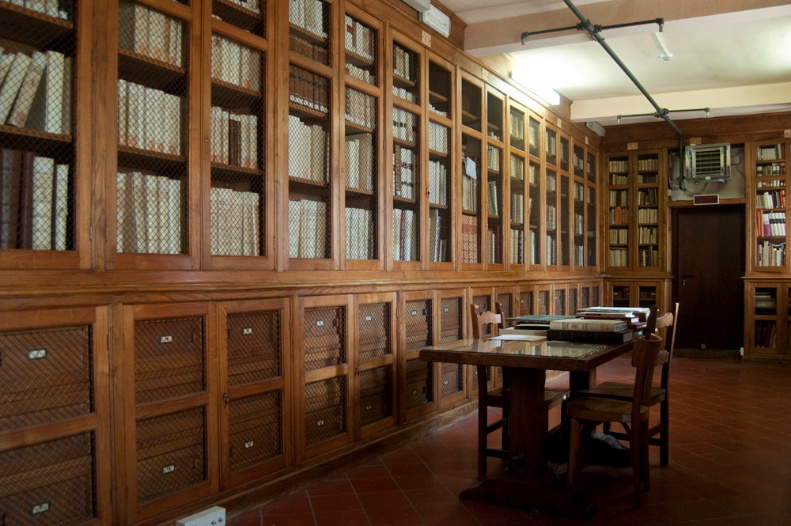

Most of the St. Scholastica collection is unpublished, and few are, compared to the vast amount of material, the documents that have had an integral paleographic transcription. “Many of them,” explains library director Dom. Fabrizio Messina Cicchetti, “have been studied and cited over time, but because of their current conditioning (folded or rolled) it is difficult to study them comfortably without harming the documents themselves. For this reason, a few years ago, a group of restorers was commissioned to design an intervention that would include the high-resolution digitization of all the parchment documents of the Monastic Archives, then the necessary flattening, restoration (of the documents and seals, where present) and new conditioning in special drawers. It will thus be possible to better enhance these documents and their precious contents allowing scholars and researchers more convenient access and the documents a more consonant preservation for their protection.” This is a first and fundamental intervention of valorization that will complete the action initiated at the end of the nineteenth century by Leone Allodi, and which will serve as a further basis for learning about and deepening the important material preserved in St. Scholastica.

Possession

PossessionThe State Library of the National Monument of St. Scholastica

The Abbey of St. Scholastica in Subiaco was founded by St. Benedict, and the library probably came into existence with the establishment of the monastery itself, although no books from the time of St. Benedict have come down to us because of the devastation suffered by the Sublacensis monasteries between the seventh and tenth centuries. After the year 1000 the abbey flourished again and the library began to be provided with books again, particularly under Abbot Umberto (1050-1069) and under Abbot John V (1069-1121). By the end of the 14th century, the library possessed about 10,000 volumes. In the years 1464-1467 the Library was enriched with the first books printed in Italy, right in the monastery of Subiaco, where the first Italian printing press was located, implanted by the German printers Corrado Schweynheym and Arnoldo Pannartz, who moved to Rome in June 1467, leaving much of the printing machinery in Subiaco, although after their departure it seems that the monks did not print any more books. Later, other incunabula were purchased in Rome from the same printers and also from other printers.

Many works were lost and many were removed especially during the invasion of the monastery in the years 1789-1799 and 1810-1815. After the Unification of Italy and the suppression of the monasteries, the public domain confiscated the property of St. Scholastica and put it up for auction, and then declared the monasteries a national monument and entrusted their custody to some monks. Don Leone Allodi was given the post of superintendent, with the task of ordering the library and manuscript collection, a task Allodi completed with uncommon competence. A new increase and better arrangement of the library took place under Abbot Salvi: during his long rule (1909-1964) it was arranged in more worthy premises and restocked with ancient and modern collections and various journals, thanks also to the financial support of the directors of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities. Today, the Library holds about 130,000 printed volumes, 15,000 documents, 3,883 parchments, 436 manuscripts and 206 incunabula, three of which were printed in Subiaco. Important holdings include the Monastic Archives, the Costa Fund (the library of famous Italian socialists Andrea Costa and Anna Kulischoff), the Colonna Archive, the Pius VI Library, and the Prints and Drawings Fund.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.