“I was walking along the road with two friends-it was sunset-I felt like a breath of melancholy. All of a sudden the sky turned blood red. I stopped, leaned against the fence dead tired - I saw the clouds blazing like blood and similar to sabers above the fjord and the pitch black city. My friends went on - I stood there, trembling with anguish - and I heard like a loud, endless cry running through nature.” Nice, Jan. 22, 1892: place and date are etched in the notebook of Edvard Munch (Løten, 1863 Oslo, 1944). The passage written that day on the Côte d’Azur, which we reproduce here in the translation published in the catalog of the Munch exhibition held in Florence in 1999, is celebrated and is an annotation that would later lead the artist to elaborate his best-known masterpiece, one of the icons of world painting: theScream, in Norwegian Skrik, or, using the German title Munch gave the work, Der Schrei der Natur (“The Scream of Nature”).

Munch never specified on which street he was walking along with his two friends, but from the description it is possible to identify the place with some ease and precision: it is the Ekeberg Hill, crossed by a street equipped with a parapet (the “fence” on which the painter leaned), and from which it is possible to enjoy a beautiful view of Oslo (which at that time was still called Christiania), where Munch had moved when he was only a year old, and of the fjord on which Norway’s capital stands. Today, moreover, there is a plaque at the site indicating it as the inspiration for the painting. It has been speculated that the “loud cry” Munch heard came from the Oslo Psychiatric Hospital, which was located at the foot of the hill and where, moreover, the painter’s sister Laura was an inpatient: the “cry that goes through nature” is rather aliterary image, which the artist must have had well in mind and which we find in a lyric by Heinrich Heine from 1888, entitled Götterdämmerung (“The Twilight of the Gods”), where we read a line that reads “Und gellend dröhnt ein Schrei durchs ganze Weltall” (“And a great cry resounds through the whole universe”). Heine’s poem may provide a good theoretical basis for interpreting Munch’s painting: the work opens with a joyful and uplifting description of the month of May, which, with its flowers, sunlight, and gentle breezes, beckons women, men, and children to it, and then goes to knock on the poet’s door, who instead, disdainfully, refuses to join in: “[May], I have looked through you and I have looked through / the fabric of the world, and I have seen far too much / and so deep, to say that all joys have faded / and endless sorrows run through my heart. / I have looked through the shells, so hard and strong / of the houses of men, and the hearts that are called human / and I have seen lies, deceit and sadness in them.” This atmosphere of grief and despondency, through an increasingly terrifying climax, reaches an anguished God who “casts away his crown and tears his hair,” and ends with the defeat of the poet’s guardian angel, following which the scream spreads across the universe, heaven and earth become confused, and “the ancient night” becomes ruler of all.

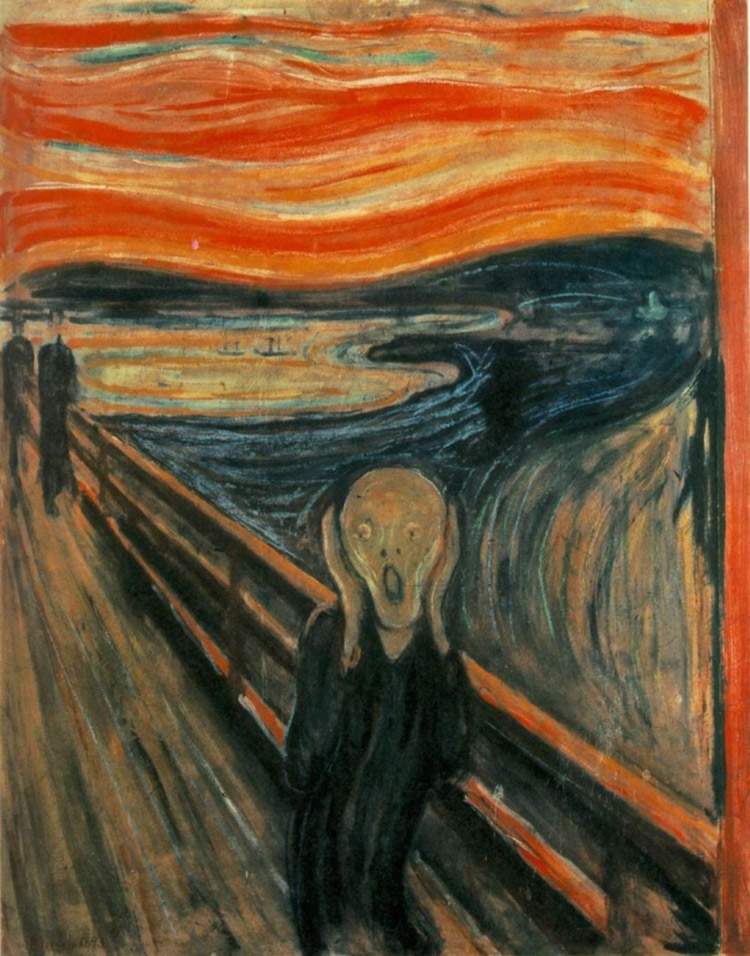

|

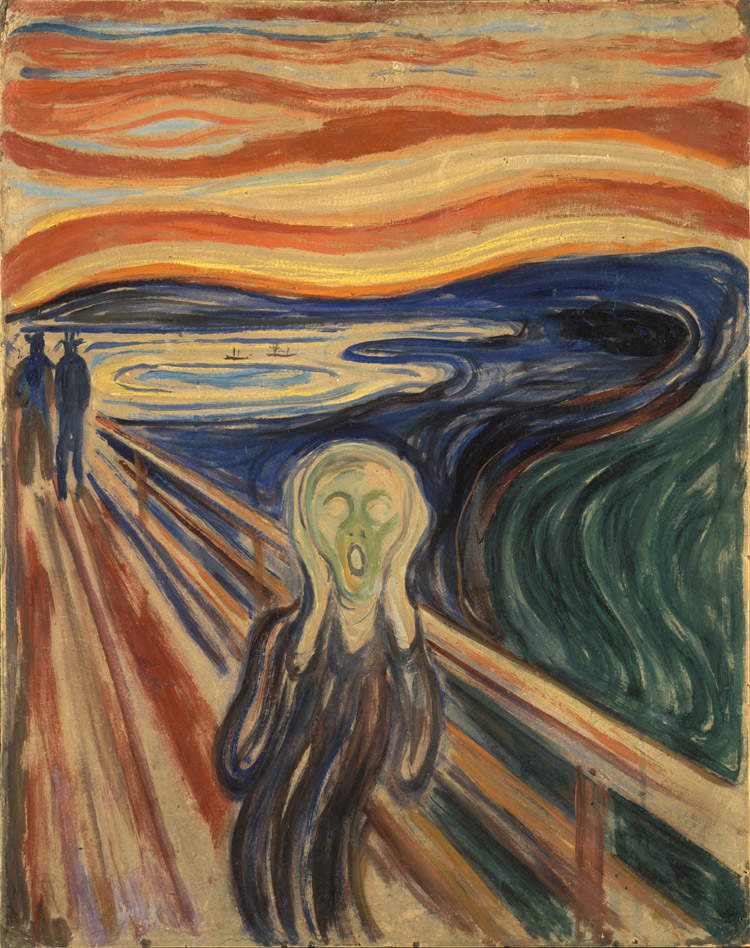

| Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893; oil, tempera and pastel on paper, 91 x 73.5 cm; Oslo, Nasjonalgalleriet) |

|

| Oslo, location of the place where Munch’s The Scream is set (from Google Maps, photo by Valera Hudoborodov) |

The image of sky and earth mingling seems to return in Munch’s painting as well: the sky, ablaze, is rendered in the form of tongues of fire looming over the inlet and the city, which are already beginning to blend in with their surroundings, whose swaying shapes recall those of the sky. In the foreground, we have the path of Ekeberg Hill, with the fence over the cliff, and on the road are the figures of two characters, further back, who seem to be untouched by the upheaval of the landscape and, in the foreground, the protagonist: has become a deformed phantom, has lost all human connotations, his body twisting in the same sinuous lines that are tearing up the environment, has turned into a kind of asexual larva that assumes a desperate expression and brings his hands to his ears, we are not sure whether to shelter himself from his own scream, the extreme manifestation of that despair that so effectively overflows from Heine’s lyric, or from the scream of restless nature. No one, until that 1893 when Munch painted The Scream, had taken the human figure to such a bold degree of deformation. But neither had anyone succeeded in providing such an iconic image of theexistential anguish that can afflict a person: the Scream, with its sound waves reverberating in the landscape, deforming it, is but a metaphor, in which the elements of nature also participate (the landscape merging with the sky, Uwe Schneede has pointed out, is a symbol of death), and which refers us, at first glance, to the philosophy of Søren Kierkegaard.

It has been pointed out how theanxiety to which Munch was subject (who, it seems, was suffering from agoraphobia and acrophobia at the time) can be related to the definition of “anguish” that Kierkegaard offers the reader of his essay Begrebet Angest (“The Concept of Anguish”), here in Cornelio Fabro’s translation: “Anguish can be compared to vertigo. He who turns his eyes to the bottom of an abyss is seized with vertigo. But the cause is no less in his eye than in the abyss: for he must look there. Thus anguish is the vertigo of freedom, which arises as the spirit is about to pose the synthesis and freedom, looking down into its own possibility, grasps the finite to stop in it. In this vertigo freedom falls. Further psychology cannot go and neither does it want to.” Anxiety, for Kierkegaard, is the typical feeling of those who are free (although those who experience it do not immediately associate it with their condition of freedom), and who consequently face choices that may involve interesting and seductive novelties, but also risky experiences. Munch strongly felt this typically fin de siècle sense of disorientation (all the more so at the time of the making ofThe Scream, when the artist was in his thirties), moreover aggravated by painful family bereavements, which invested his worldview, as well as individual aspects of his life, giving rise to theexistential angst that, in his masterpiece, takes the form of a scream that blurs the landscape (the anxiety that undermines certainties and throws man into instability).

We know for a fact that Munch, an avid reader, was familiar with Kierkegaard’s philosophy: he himself affirms this in one of his letters, although the latter concerns a later period than the one in which the artist made TheScream and contains the statement that Kierkegaard’s philosophy, for Munch, is a recent fact. It is, moreover, a letter in which Munch establishes some firm points of his own literary and philosophical outlook: “I am tired of being associated with the German school (regardless of the esteem I have for the achievements of the great Germans in art and philosophy). We, here, have Strindberg, Ibsen, and others, and also Hans Jæger. Also, strangely enough, I have been able to read Søren Kierkegaard only in recent years” (from letter to Swedish art historian Ragnar Hoppe, dated November 5, 1929). If, therefore, we were really to consider Munch’s approach to Kierkegaard as late, certain aspects ofThe Scream might nevertheless be helped by his association with the playwright August Strindberg, whom the Norwegian painter met precisely in 1892. Strindberg, who at that time had already written dramas such as Miss Julie or The Father, had also started from a well-settled realist substratum and then plumbed the depths of the psyche, reaching devastating conclusions dominated by pessimism: like Munch, Strindberg is an artist who criticizes the hypocrisy of society, feels a certain unease, and has a deeply gloomy worldview. The closeness between the two is also evidenced by the review Strindberg wrote of TheScream in the magazine La revue blanche in 1896, describing the work in these terms: “Cri d’épouvante devant la nature rougissant de colère et qui se prépare à parler pour la tempête et le tonnerre aux petits étourdis s’imaginant être dieux sans en avoir l’air. Crépuscule. Le soleil s’éteint, la nuit tombe, et le crépuscule transforme les mortels en spectres et cadavres, au moment où ils vont à la maison s’envelopper sous le linceul du lit et s’abandonner au sommeil. Cette mort apparente qui reconstitue la vie, cette faculté de souffrir originaire du ciel ou de l’enfer” (“Scream of fright before nature blushing with wrath and preparing to speak through storm and thunder to the confused little men who imagine themselves to be gods without having the semblance of one. Twilight. The sun goes out, night falls, and twilight transforms mortals into specters and corpses as they go home to cover themselves under the sheets of their beds and surrender to sleep. This apparent death that recreates life, this faculty of suffering originating in heaven or hell.”).

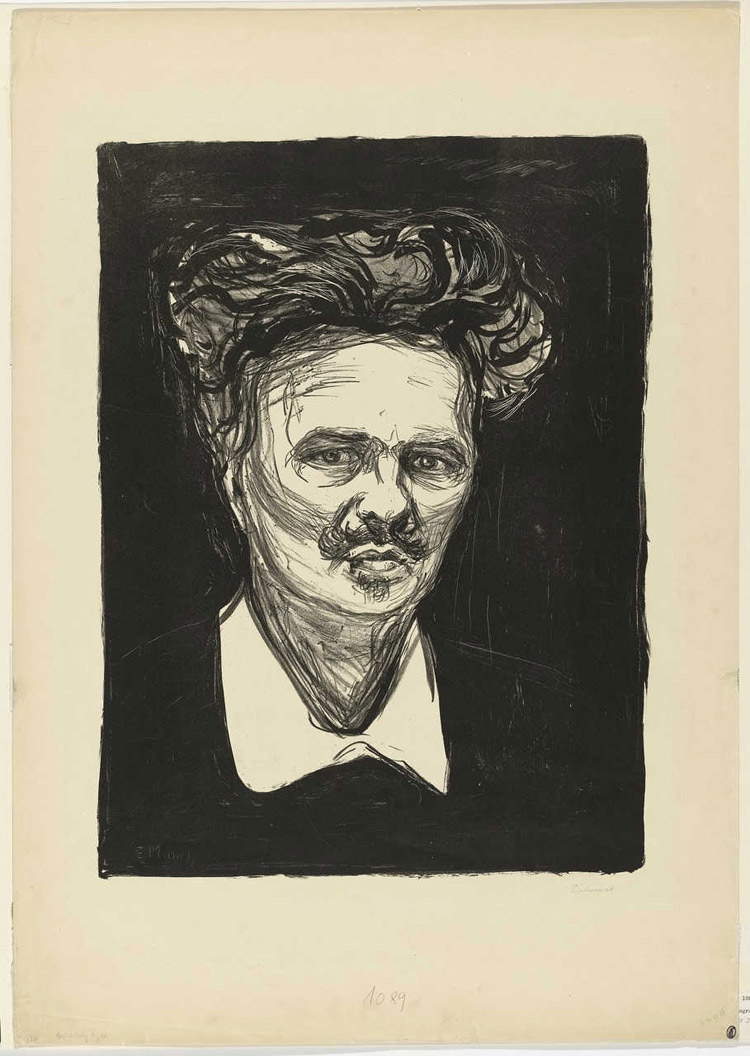

|

| Edvard Munch, Portrait of August Strindberg (1896; lithograph, 50.5 x 37.8 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art - MoMA) |

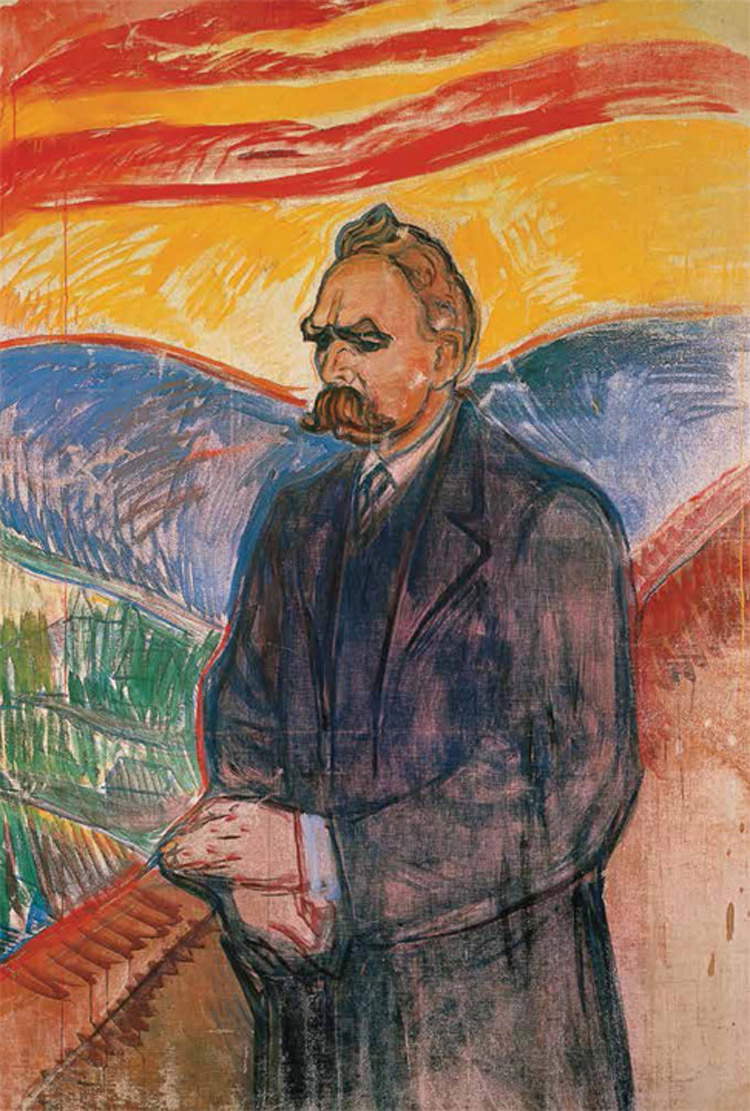

Strindberg, moreover, was probably the conduit between Munch and Friedrich Nietzsche, an author with whom the Swedish playwright was in correspondence. Nietzsche is another author who could constitute one of the pillars of the philosophical framework of TheScream: it has been emphasized that the cry that comes out of the mouth of the protagonist of the Norwegian’s painting could be a kind of embodiment of Nietzsche’s very famous aphorism 125 of Gaia scienza (“Die fröhliche Wissenschaft” the original title), below in Ferruccio Masini’s translation: “Have you heard about the mad man who lit a lantern in the clear morning light, ran to the marketplace and shouted incessantly, ”I seek God! I seek God!“? [...] The mad man leapt into their midst and pierced them with his glances, ”Where has God gone?“ he shouted, ”I want to tell you! We killed him - you and me! We are all his murderers! [...] God is dead! God remains dead! And we have killed him! How shall we, the murderers of all murderers, console ourselves? What most sacred and most mighty the world possessed until now has bled out under our knives - who will cleanse this blood from us? With what water could we wash ourselves?“).” The interpretation of the “death of God” as a cause of bewilderment and existential anguish and as a condition that sanctions the advent of nihilism (philosopher Franco Volpi, in his book dedicated to nihilism, writes that the Nietzschean image “symbolizes the coming apart of traditional values” and “becomes the thread for interpreting Western history as decadence and providing a critical diagnosis of the present.” Nietzsche himself after all, in his posthumous Fragments, had specified that “nihilism” means “that the supreme values are devalued”) could stick to the painting of Munch, who knew La gaia scienza and who, some critics (including Mario De Micheli) note, was precisely under the spell of Nietzsche’s nihilism. Volpi again comes to the rescue: “Nihilism is thus the ”lack of meaning“ that takes over when the binding force of the traditional answers to the ”why?“ of life and being fails, and this happens along the historical process in the course of which the supreme traditional values that gave answers to that ”why?“ - God, truth, the Good - lose their value and perish, generating the condition of ”meaninglessness“ in which contemporary humanity finds itself.”

Nietzsche’s contribution would, however, be much more extensive. One example: in Also sprach Zarathustra (“Thus I speak Zarathustra”), the well-known 1891 work, we read, “Of all that is written I love only what one writes with one’s own blood. Write with blood: and you will learn that blood is spirit.” Blood is a metaphor for the artist’s sincerity: for this reason, what lies behind writing (as well as art) has a relevance that could even be considered superior to the modes of expression. Munch, in this sense, is an artist who paints with blood, and in doing so he more or less consciously embraces the Nietzschean idea of the physiology of art.

|

| Edvard Munch, Posthumous Portrait of Friedrich Nietzsche (1905-1906; oil on canvas, 200 x 130 cm; Oslo, Munchmuseet) |

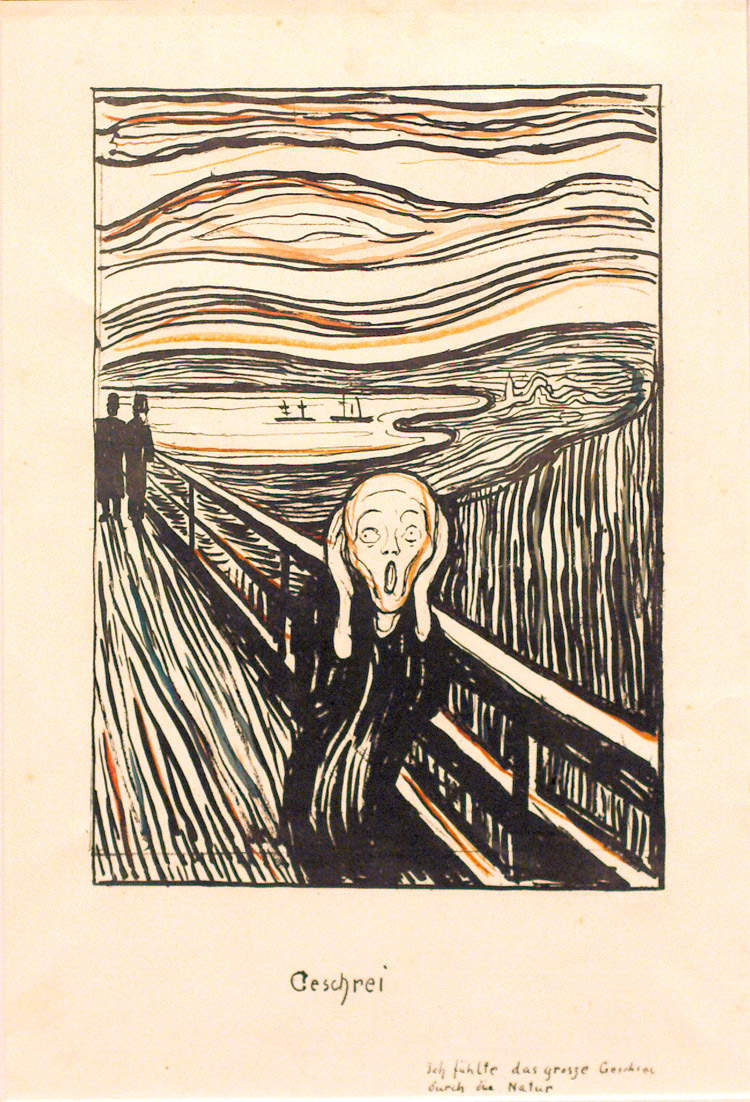

It is also worth pointing out possible connections with Arthur Schopenhauer, who, in his Philosophie der Kunst, established, regarding the degree of expressiveness to which art can reach, that the limit of art would consist in its inability to reproduce “das Geschrei,” “the scream,” “the cry” (the references, in Schopenhauer, were to the famous Laocoon group and Guido Reni’s Slaughter of the Innocents: works of art, for the German philosopher, are “essentially silent”). According to art historian Arne Eggum, Munch, with his Scream, proposed the solution to the problem posed by Schopenhauer by appealing to the emerging psychological theory of synaesthesia, according to which a perception of a certain kind could produce consequences pertaining to a different sensory sphere: thus, impulses from the vision of certain shapes and certain conditions of light and color could grant the observer the perception of a sound (and vice versa), so much so that in reference to theScream there was even talk of “sound color.” A (perhaps rather tenuous) foothold to this view might be provided by Munch himself in the description given under a lithographic version of TheScream dating from 1895, where we read the title Geschrei, which echoes the exact term used by Schopenhauer, and the phrase “Ich fühlte das grosse Geschrei durch die Natur” (“I felt the loud cry through nature”): Munch, according to Eggum’s interpretation, would have used the form “Geschrei” instead of the form without the prefix “Ge,” precisely to allude to Schopenhauer’s findings. However, we have no certain evidence that, as early as 1893, Munch was familiar with Schopenhauer’s work.

|

| Edvard Munch, The Scream (1895; lithograph, 49.4 x 37.3 cm; Oslo, Gundersen Collection) |

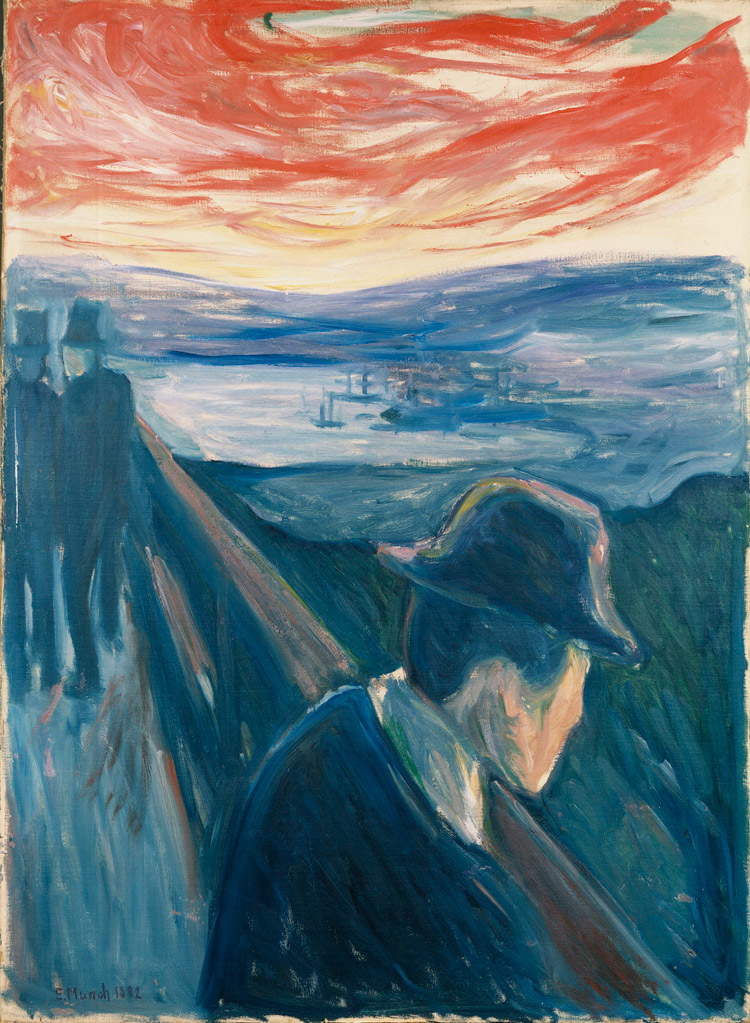

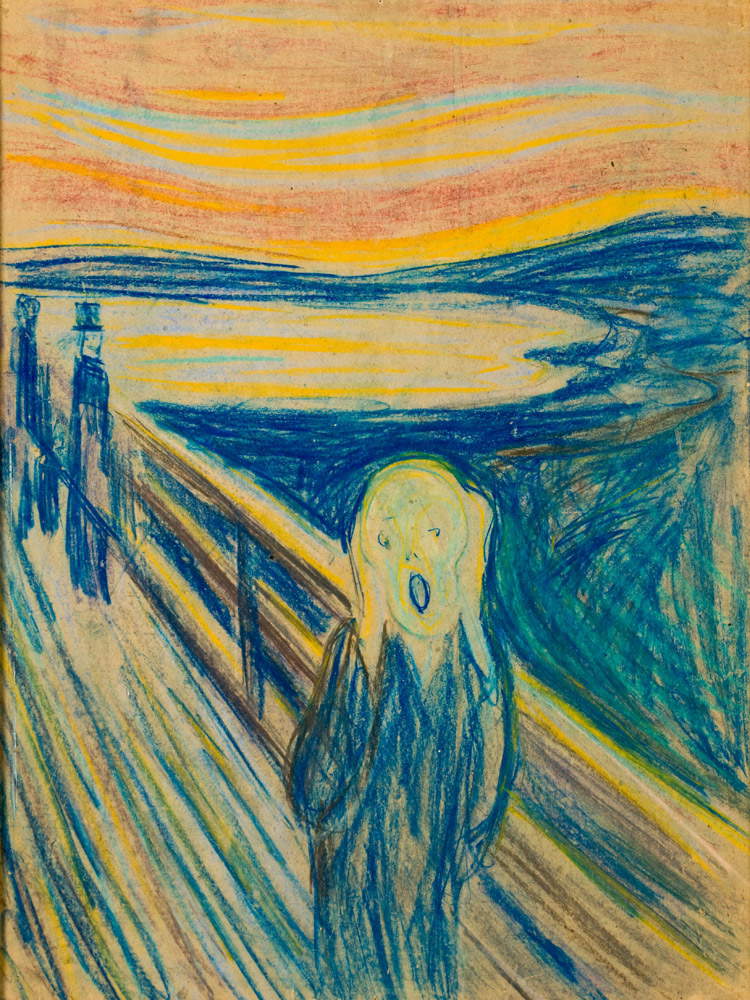

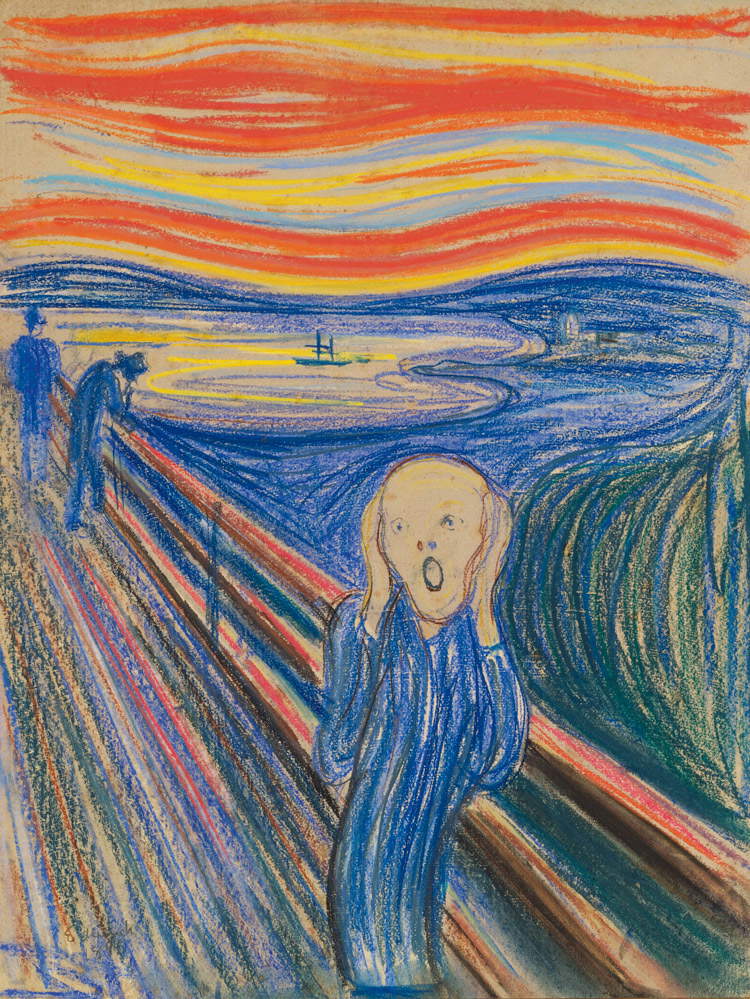

Since mention has been made of the 1895 lithograph, it may be useful to conclude by devoting quick mentions to the various versions of The Scream, to which, however, it is appropriate to add a further masterpiece by Munch, Despair, a work from 1892, which is mentioned here because it is set in the same place and at the same spot: Munch exhibited it in the fall of that year, titling it Atmosphere at Sunset, only to change the designation in the second edition of the exhibition catalog to Sick Atmosphere at Sunset. There are several versions of this painting as well, and as with theScream, the idea for Despair was born during the February-March 1892 stay in Nice. The first version of TheScream is a pastel on cardboard considered to be the sketch for the oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard painting now in the National Gallery in Oslo, which is the second version in chronological order (but, we may say, the first painting). Munch then executed a further pastel version in 1895, the same year as the lithograph: this is the only Howl in private hands (it went to auction at Sotheby’s in 2012 for around $120 million). Finally, there is a fourth Howl, in tempera on cardboard, known to have been stolen, along with the celebrated Madonna, in 2004 (ten years after the National Gallery’s theft of the painting, which occurred on the day the Winter Olympics in Lillehammer were opening), and found, as were the rest of the loot, in 2006. The fourth version dates from 1910 and is the last of the great masterpiece by the painter who anticipatedExpressionism.

|

| Edvard Munch, Despair (1892; oil on canvas, 92 x 67 cm; Stockholm, Thielska Galleriet) |

|

| Edvard Munch, The Scream (1893; pastel on cardboard, 74 x 56 cm; Oslo, Munchmuseet) |

|

| Edvard Munch, The Scream (1895; pastel on cardboard, 79 x 59 cm; Private collection) |

|

| Edvard Munch, The Scream (1910; tempera and oil on cardboard, 83 x 66 cm; Oslo, Munchmuseet) |

Reference bibliography

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.