by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 29/10/2017

Categories: Works and artists

- Quaderni di viaggio / Disclaimer

The Jerusalem of San Vivaldo in Montaione is a sacred mount in Tuscany that faithfully reproduces the holy places of Jerusalem. With several exciting terracotta sculptures.

A "place where all the mysteries of the Lord’s Passion are found, expertly depicted, as well as devout chapels, some of them splendid, arranged like those in Jerusalem": this was the concise description Bishop Francesco Gonzaga (Gazzuolo, 1546 - Mantua, 1620) provided for the Sacred Mount of San Vivaldo in his De origine Seraphicae Religionis Franciscanae eiusque progressibus, published in 1587. From the village of Montaione, in the heart of Valdelsa (and thus of Tuscany), to reach the Sacred Mount one must follow a winding but comfortable road that, among woods of holm oaks and chestnut trees, leads to the early 16th-century monastery that was built right in the middle of those woods in which, at least three centuries earlier, hermit monks had already been wandering. Here had lived for a long time that Vivaldo Stricchi da San Gimignano who, following his disappearance that one wants to place on May 1, 1320, became the object of a widespread cult in these lands, and later became a saint by popular acclamation (he was never canonized: beatification came only in 1908, but the Church had never hindered his cult). The convent was built precisely where, according to tradition, stood the chestnut tree within which Blessed Vivaldo had carved out a small cell where he could spend his ascetic hermitage. Uncertain, however, are the historical news about the personage, and moreover the toponym "San Vivaldo" predates him: there are documents from the 13th century that already speak of a "locus" or "ecclesia sancti Vivaldi," as well as "de possessioni[bus] Sancti Vivaldi quas habebant Fratres de Cruce."

More uncomfortable, however, must have been the route that, in the sixteenth century, led pilgrims here, who had to climb from the village into the middle of the forest until they reached the Selva di Camporena, the place where, in the jubilee year 1500, it was decided to build the little Jerusalem of San Vivaldo. But as steep and uncomfortable as it was, such a route was little compared to the dangers to which pilgrims would be subjected should they wish to travel to the Holy Land. The idea of building, in the woods near Montaione, a Sacro Monte that would reproduce, in miniature, the topography and chapels of the real Jerusalem, arose precisely out of the need to offer pilgrims an alternative to a risky journey to be faced at a time when the strong Ottoman expansionism endangered the safety of those heading to the East. This was the same spirit that, a few years earlier, had given rise to the Sacro Monte of Varallo, another complex of small chapels that mimicked the holy places of Jerusalem. The Piedmontese Sacred Mount was conceived by Father Bernardino Caimi (Milan, 1425 - 1500) who, returning from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, had realized how many threats the long journey entailed, and wanted to offer pilgrims a faithful reproduction of the places where the earthly story of Jesus Christ unfolded. Probably Bernardino Caimi, during his stay in Palestine, had contacts with Friar Thomas of Florence (documented from 1506 to 1529), a Franciscan who had made several trips to the East and who, knowing what Caimi had accomplished in Varallo, resolved to create a miniature Jerusalem in Tuscany as well.

The Franciscans thus arrived in Montaione in 1500, began to build the monastery and, shortly thereafter, began to bring Fra Tommaso’s project to life. It took sixteen years to build the thirty-four chapels envisaged by the project: the Pontifical Brief of Leo X, dating from 1516, granted indulgences to the faithful who had made a visit to the loci of San Vivaldo, which were minutely listed in the document. Of the original thirty-four oratories, erected in imitation of those in the real Jerusalem, only thirteen remain today, to which are added five built in later periods, for a total of eighteen chapels, each granted in patronage to a local family. There is no single tour route for the chapels: the pilgrim could decide whether to follow the Gospel narrative, to move according to the layout of the sites on the map of Jerusalem, or to follow the simple succession of chapels. The route we are about to take below is the one suggested by art historian Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, a longtime official of the Superintendency of Florence with various duties in Valdelsa, of which she is a profound connoisseur, as well as the author of the most up-to-date guide to the Jerusalem of San Vivaldo. This is an itinerary that, keeping in mind functional needs, mostly follows the narrative of the Passion of Christ as described in the chapels. Each of them, in fact, houses terracotta sculptural groups illustrating the different episodes of the Gospel narrative: the aim was to make the faithful an actor of the events, to make them participate in the first person and to involve them in the sufferings of Christ. It is an itinerary endowed with a very strong emotional impact, capable of captivating even non-believers, also by virtue of several passages in which the visitor discovers himself in the midst of the sculptures, called upon to be a part himself of the events narrated. In this sense, terracotta becomes a more suitable tool for shaping the message of the Franciscans of San Vivaldo: earth is a poor and simple element, thus full of symbolic references, and from the practical side it allowed sculptures to be modeled durable over time relatively quickly. The terracottas of the Jerusalem of San Vivaldo are dense with a naturalism that lends a vivid concreteness to the scenes narrated: simplicity, closeness to the pilgrims who came to this place, and the ability to communicate the message clearly and directly are the main characteristics of the sculptures that populate the loci of San Vivaldo and that were executed by some of the leading masters of the time, from Giovanni della Robbia (Florence, 1469 - 1529/1530) to Benedetto Buglioni (Florence, 1459 - 1521).

|

| The convent of San Vivaldo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

After visiting the church of San Vivaldo, adjacent to the convent, it is possible to indulge in a first, brief stop at the Chapel of the Samaritan Woman: it is an open loggia within which is the relief depicting the episode, taken from the Gospel of John, of the encounter between Jesus and the Samaritan woman. It is, however, a copy: the original terracotta, from the workshop of Giovanni della Robbia, was sold in 1912, when the convent needed funds to repair chapels that had fallen into disrepair (today it is in the United States, at the Cleveland Museum of Art). The chapel, on the other hand, is one of the four not included in the original plan and bears witness, writes Proto Pisani, to "how the philological rigor that had characterized Fra’ Tommaso’s project had gradually been lost" and "how there was a tendency to venerate all the places that could recall episodes from the life of Jesus." The real journey can thus begin with the chapels of Mount Zion, which share a single building. The first is the Chapel of the Cenacle, which welcomes us with its classical facade, in a sober and austere Renaissance style that characterizes all oratories. It is the first chapel to reproduce a Jerusalemite sacred place, for the Sanvivaldine sacellum echoes the scheme and plan of the Cenacle in Jerusalem: however, the latter’s medieval forms are "actualized" in a Renaissance layout with a classical flavor, consonant with the humanistic ideals of Tuscany at the time. Within the chapel are the groups of the Washing of the Feet and theLast Supper, both attributable to Giovanni della Robbia and his collaborators.

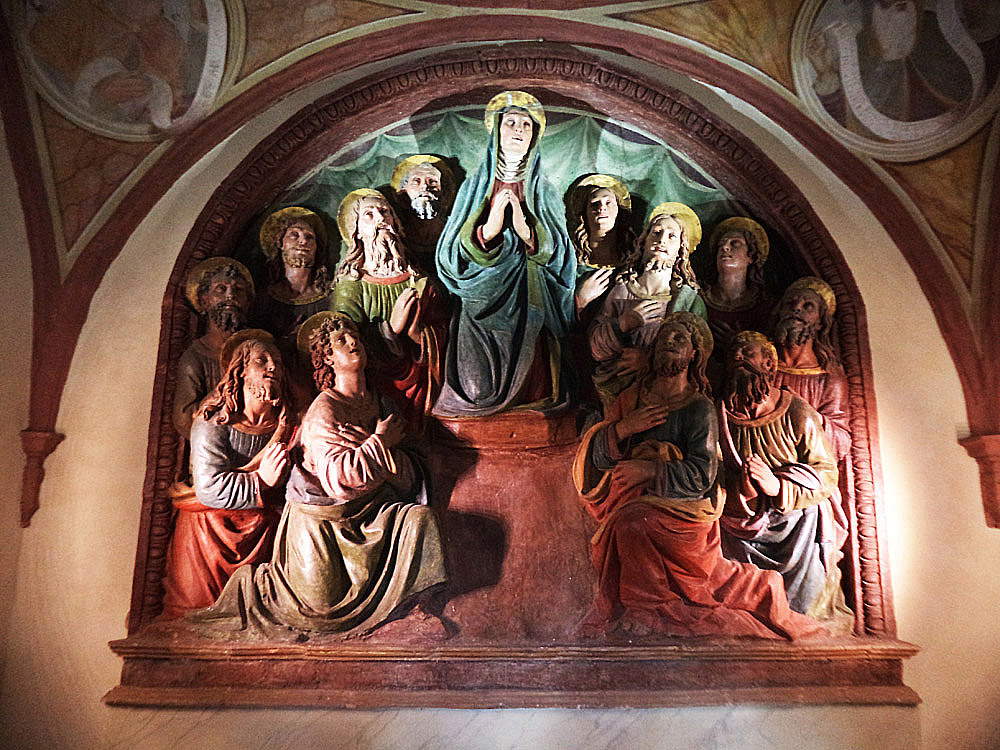

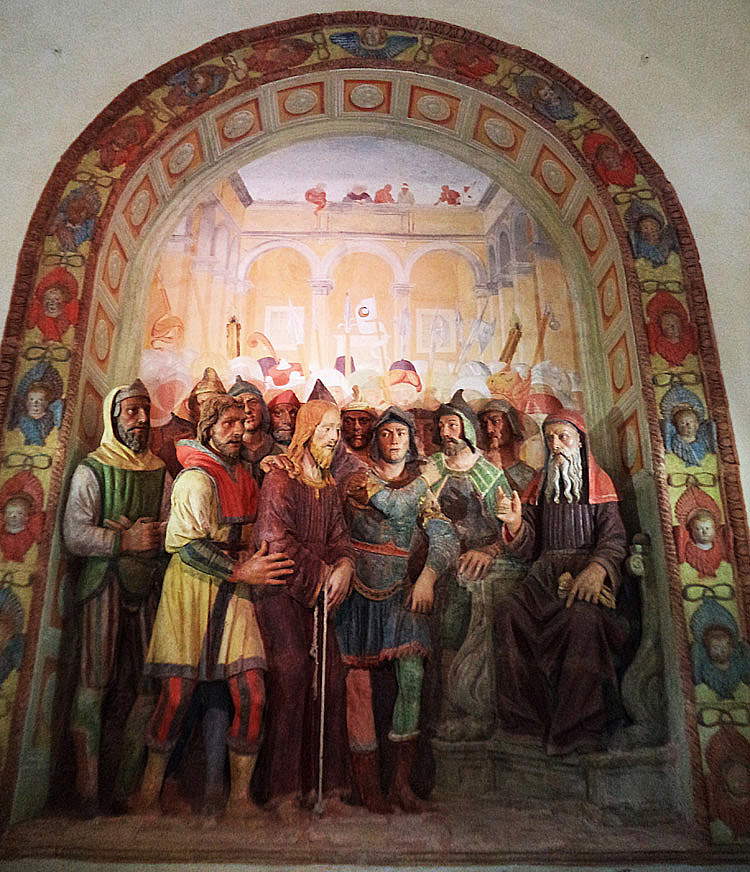

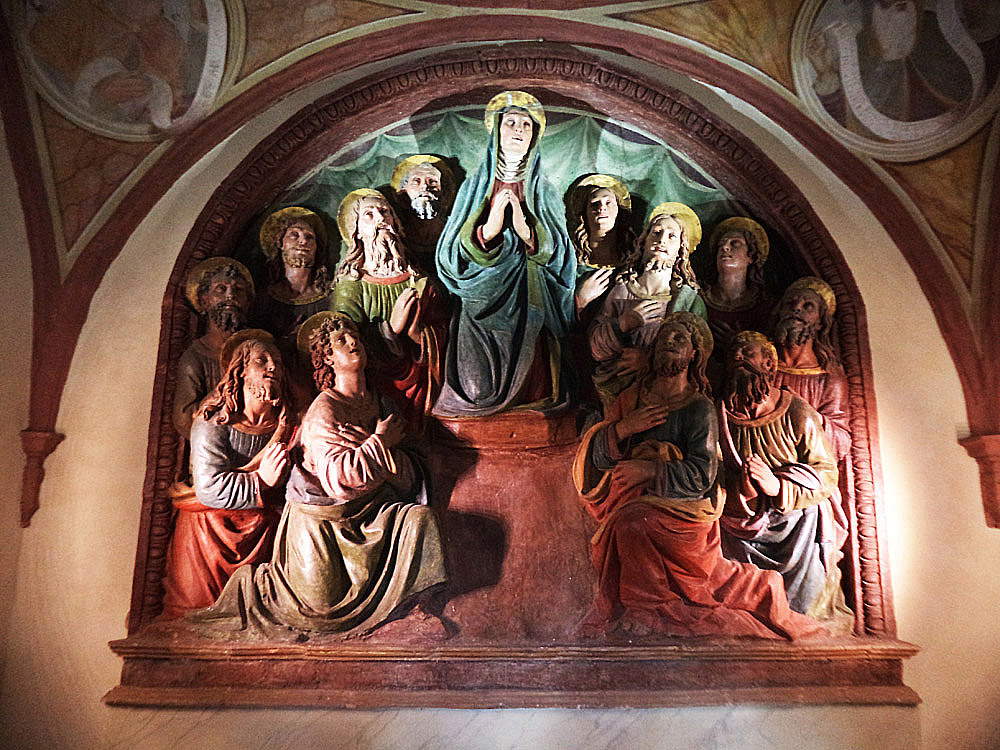

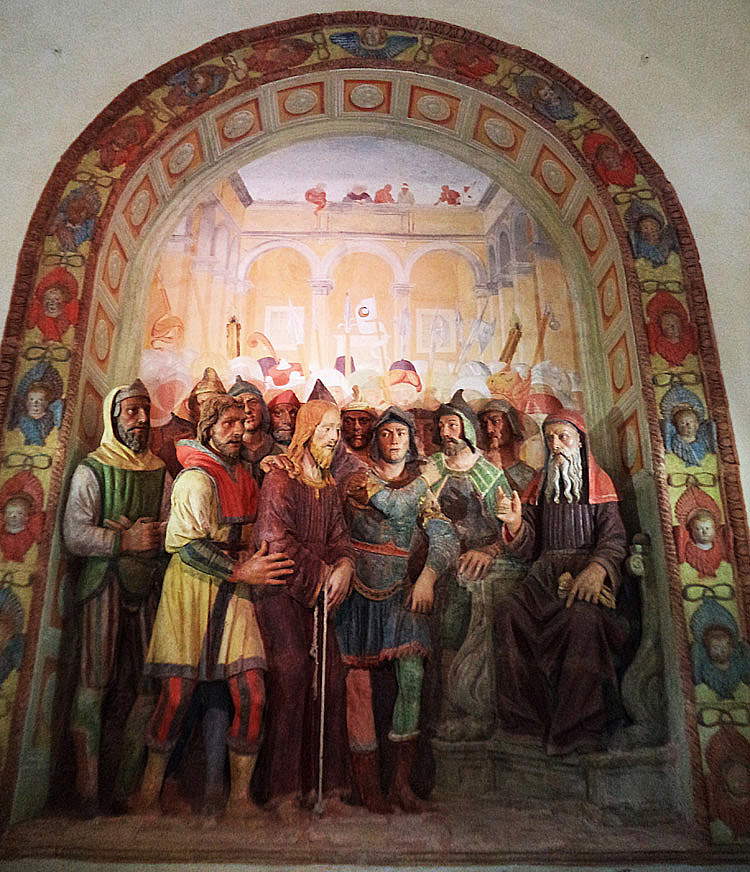

The pilgrim begins to feel part of the narrative: the characters are endowed with a strong individual characterization, there is a marked taste for narrative, close to the visitor’s daily experience (the objects reproduced on the table of Christ and the apostles are those in use at the time the works were created), there is an engaging and tense gestural expressiveness, which prepares, in this chapel, the visitor for the dramas he will experience in the continuation of the tale. A narrative that abandons the Gospel sequence for a moment to follow the layout of the Jerusalem chapels: one continues in fact with the Chapel of the Incredulity of St. Thomas, where the group is likely the work of Agnolo di Polo (Florence, 1470 - Arezzo, 1528), a pupil of Verrocchio (and Agnolo’s work presents strong points of contact with the famous Incredulity of St. Thomas that Verrocchio executed for Orsanmichele in Florence), and with the Chapel of Pentecost, whose sculptural group is instead attributed to Benedetto Buglioni. The involvement is total: in the dome it is possible to see the dove of the Holy Spirit descending with its tongues of fire on Mary and the apostles (but also on us who witness the scene). The journey resumes, leading us to the House of Anna, the place where Jesus’ trial was held. When the door opens wide, we find ourselves in the midst of the trial: Jesus, head bowed, looking down and with his hands tied, is led by a handful of soldiers in front of the high priest Annas, who grimly stares at him, questioning him, while the soldier next to him raises his arm to slap him. The moment is particularly heated, and the visitor is suddenly catapulted into the middle of the scene: it is impossible to remain indifferent to these inhuman and cruel gestures. Leaving the chapel and continuing on our way still astonished, we pick our way back to the House of Simon the Pharisee, which, with the engaging group assigned to Agnolo di Polo, makes us almost diners at the dinner where the Magdalene repents by throwing herself at Jesus’ feet and takes us back to the stages of the story (but it follows the topography of Jerusalem, though not part of the original design).

|

| The Chapel of the Samaritan Woman. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Exterior of the Chapel of the Cenacle. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Interior of the Chapel of the Cenacle. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Upper Room. Ph. Credit Jerusalem of San Vivaldo |

|

| The washing of the feet. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Incredulity of St. Thomas. Ph. Credit Jerusalem of St. Vivaldo |

|

| Pentecost. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte. |

|

| The dome of the Pentecost Chapel. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Jesus in front of Anna. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Jesus in front of Anna, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The dinner in the house of the Pharisee. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

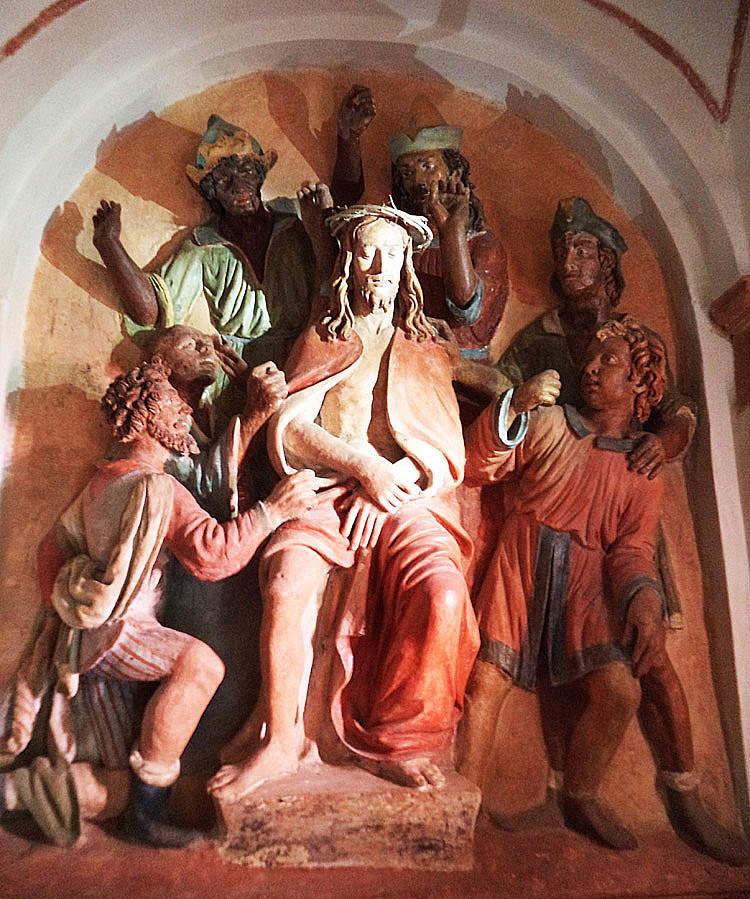

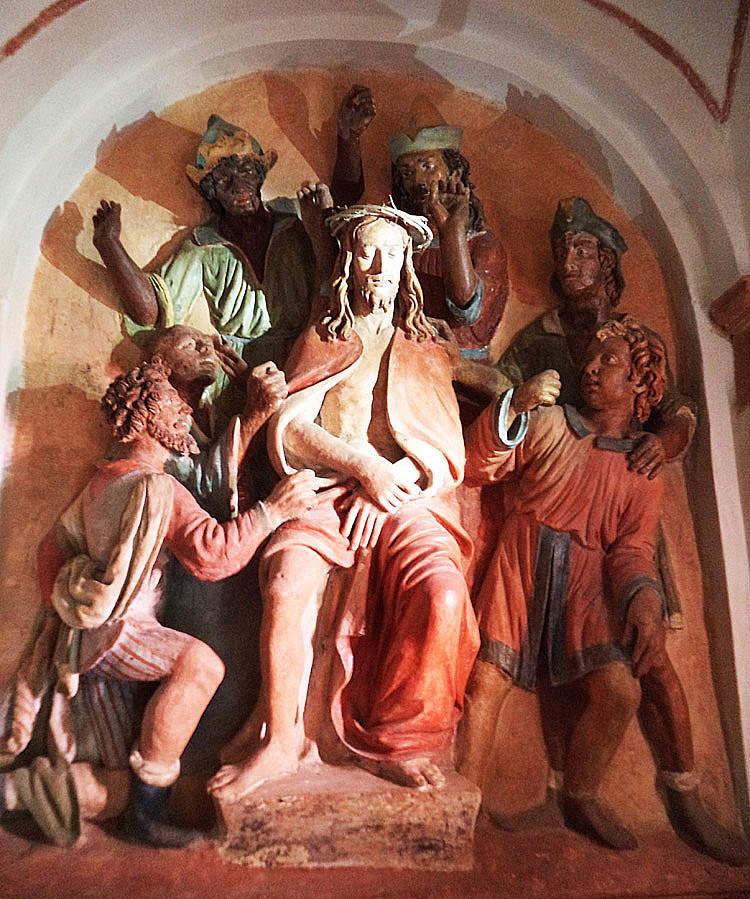

The next group of chapels begins the Via Dolorosa, and our sensibilities are constantly externalized: Jesus’ journey begins, which, after being judged, will take him to Calvary. In the Chapel of the House of Pilate, we witness the Flagellation and theCoronation with Thorns, scenes attributed to Agnolo di Polo: the naturalism, with the bland faces of the thugs who deal with Christ and with the visible suffering that can be read on the Lord’s face, touches here one of the highest peaks of the entire Sanvivaldine complex. But perhaps the most moving passage in all of Saint Vivaldo’s Jerusalem is the corridor that runs between theaedicule of Ecce Homo and theaedicule of the Crucifix, carved out of a wall of the Chapel of the Going to Calvary and one of the Chapel of Pilate’s House, respectively. Here, the involvement is total. This is how a great art historian, John Shearman, spoke of it in his Art and the Spectator in the Italian Renaissance: "In this case the pilgrim-spectator comes to find himself in a meager space between two groups, a short distance apart, facing each other. He finds himself, without escape, next to theEcce homo, and the other group crowds right behind him, including the grieving mother of Christ." The audience, as in the whole complex, was (and is) called again "to cancel all historical distance in order to participate in that experience as if it were repeated in that moment, in the spirit of devotional exercises and ultimately of faith in salvation." And in this passage one has the distinct, strong, vivid feeling of being part of the crowd called upon to choose between Jesus and Barabbas: the sculptures, probably executed by Benedetto Buglioni (the Crucifix crowd) and Marco della Robbia (Florence, 1468 - 1534), who would instead make theEcce Homo, are also characterized here by their very strong concreteness (note the weeping of Mary’s face, which moves to emotion). One almost seems to hear the cries of the crowd shouting “Crucifige!” (“Crucify him!”), and the despair of Jesus’ mother, and of the apostles. Difficult to account for with photographs, not least because the two groups are facing each other: one must necessarily see live.

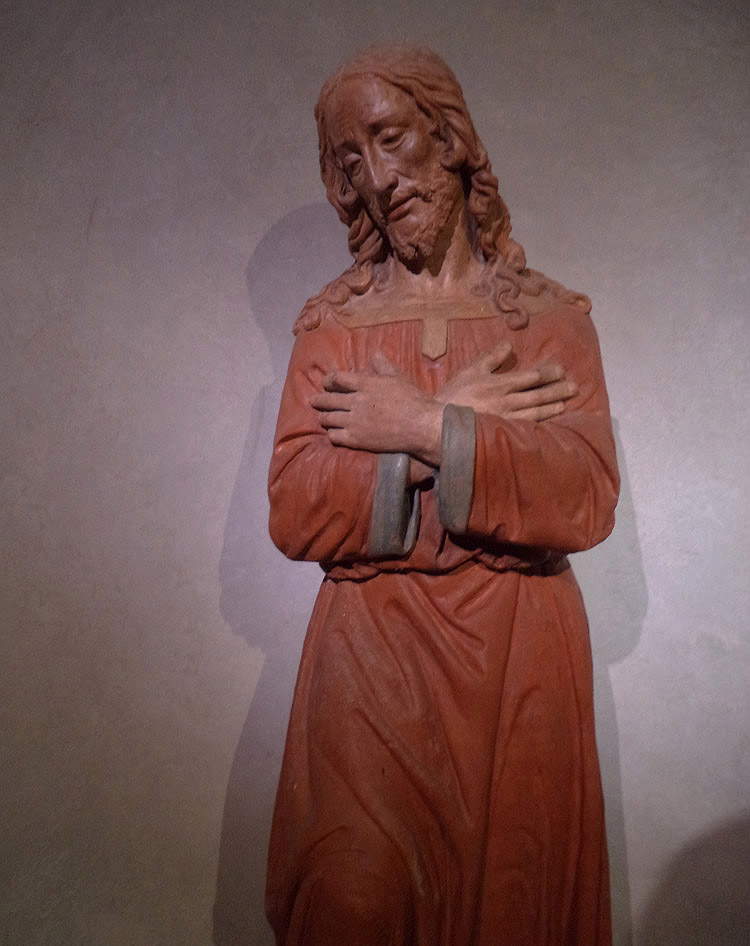

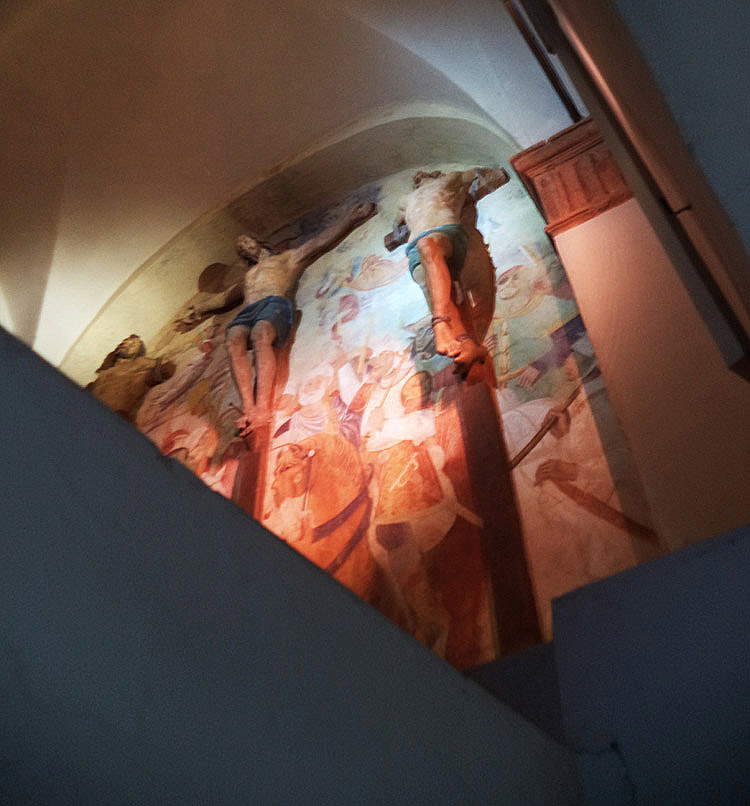

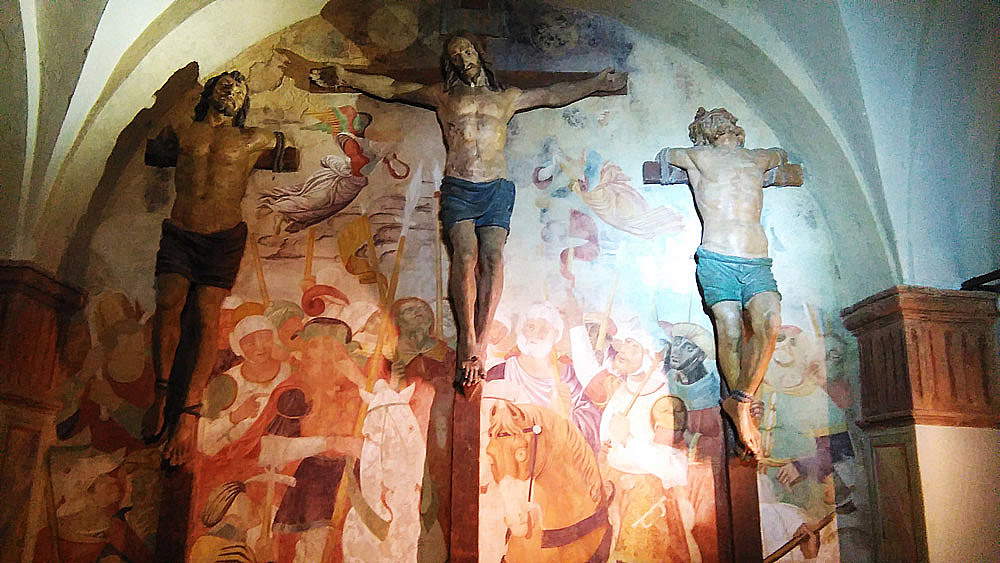

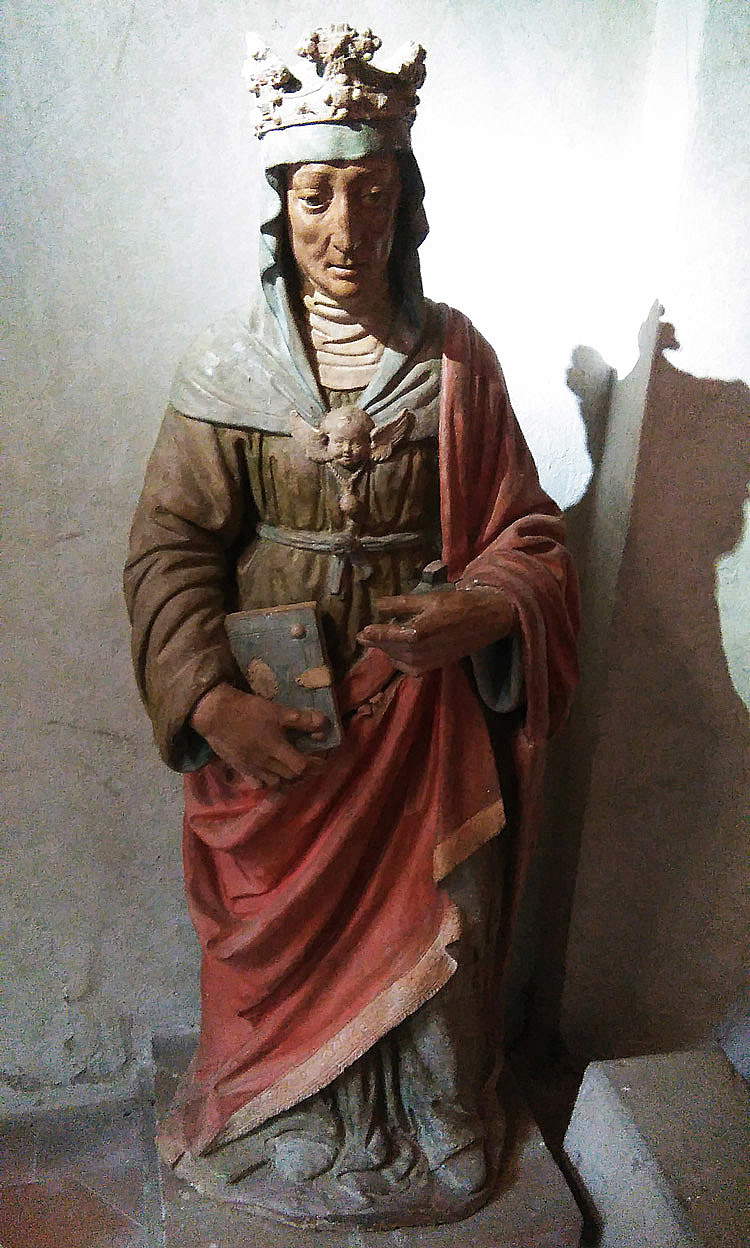

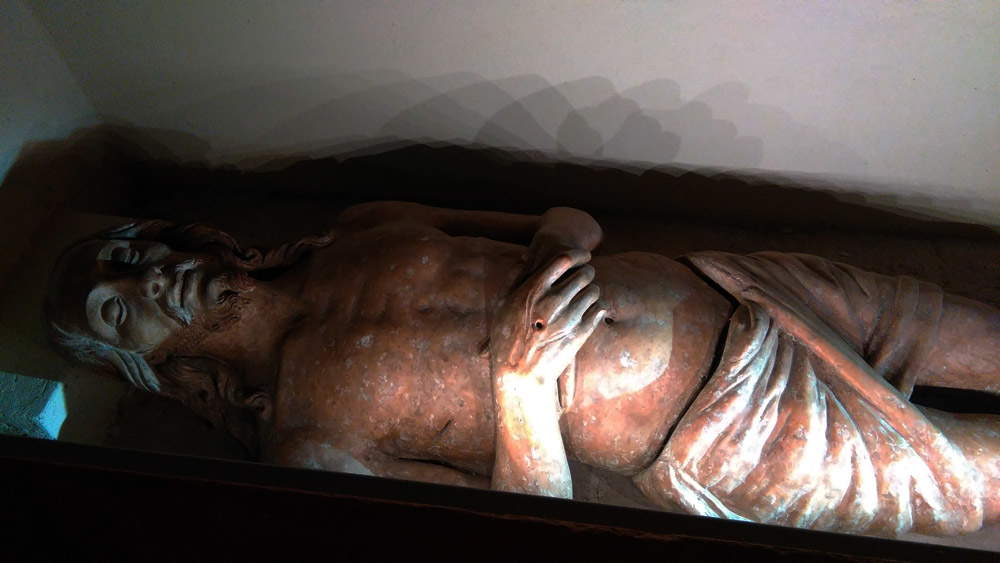

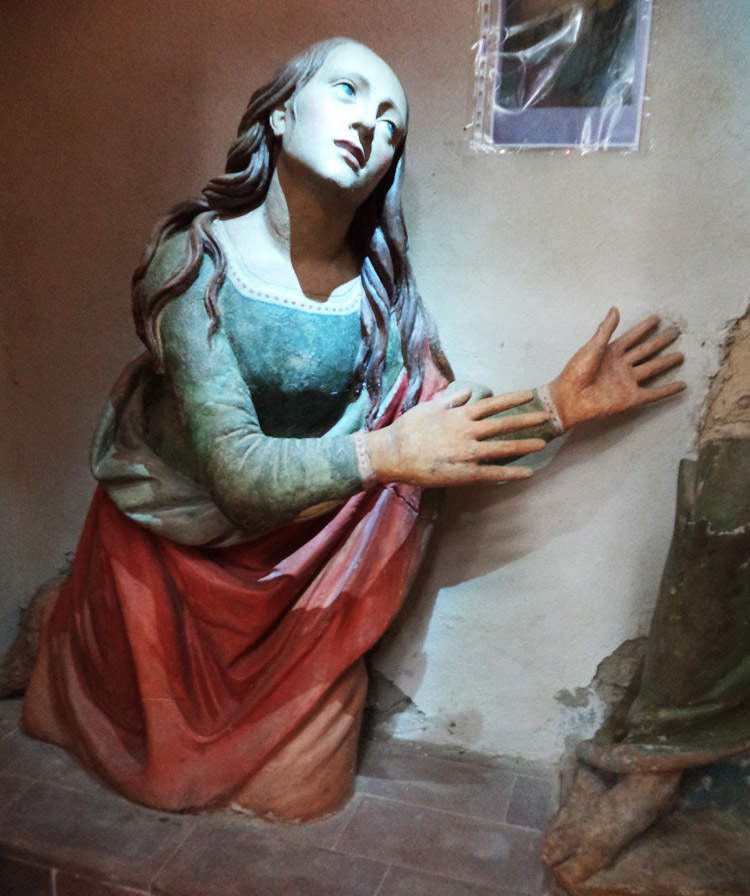

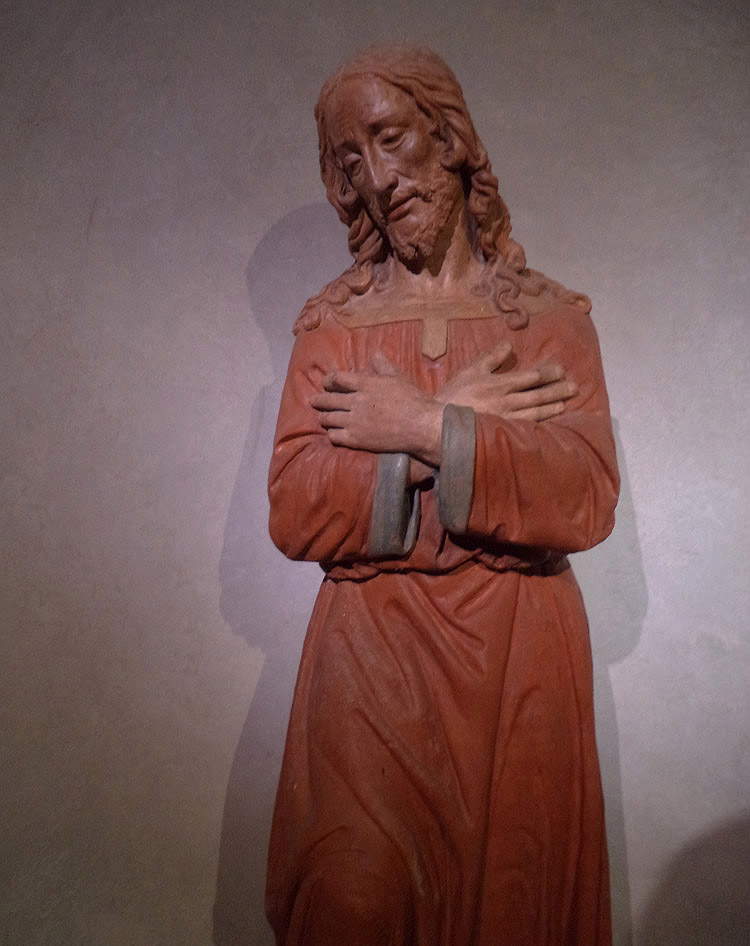

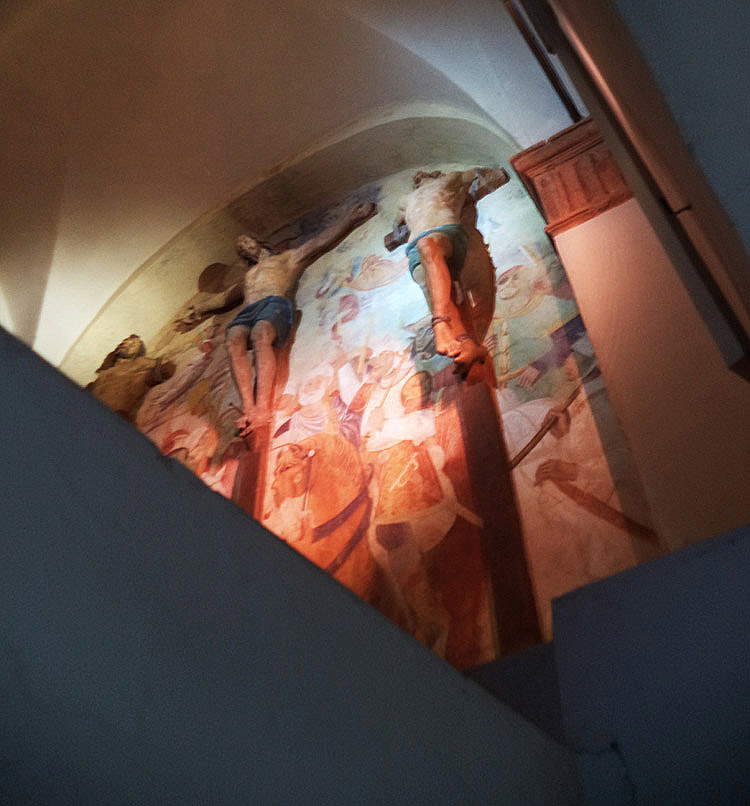

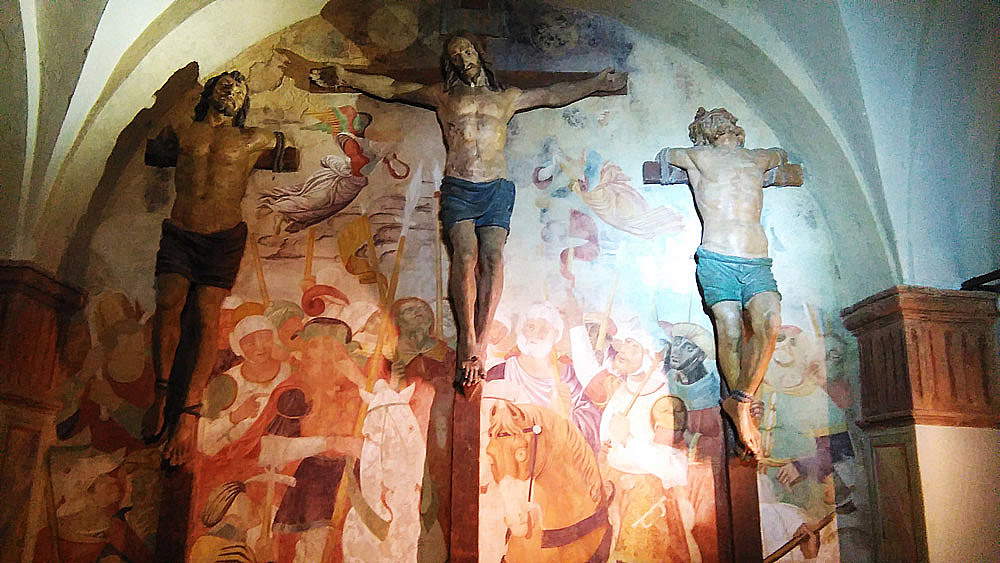

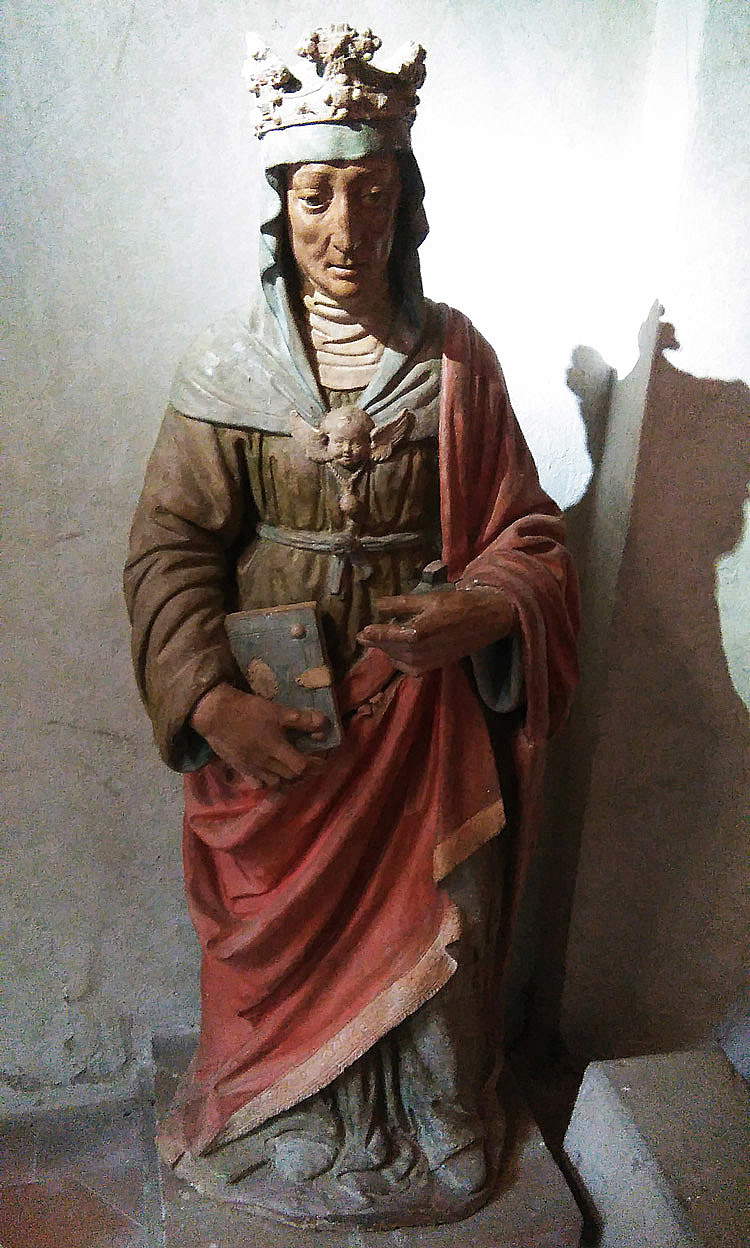

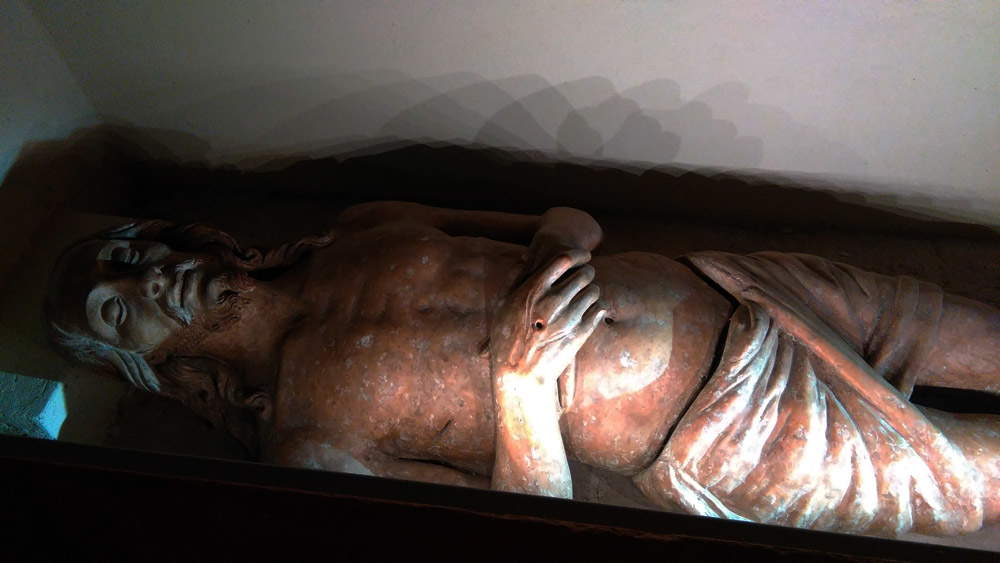

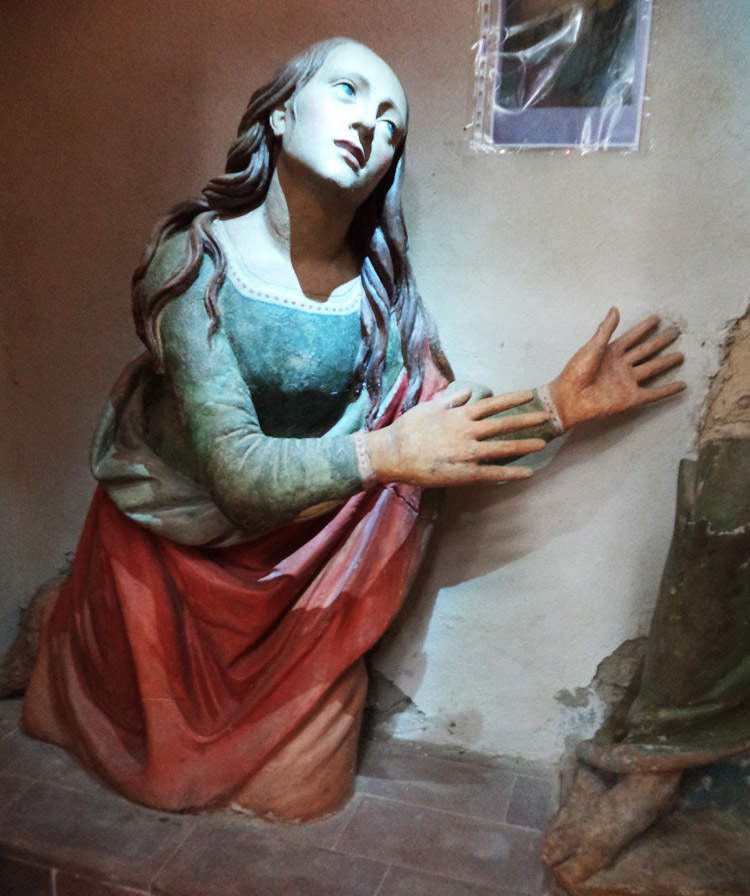

Intense sensations are also experienced in the Chapel of the Going to Calvary: the figures attributed to Agnolo di Polo are arranged horizontally, so that entering from the main entrance we almost seem to be following the sad procession. The next Chapel of the Madonna of the Spasimo includes another of the most intense moments, with the group ascribed to Giovanni della Robbia: the Madonna can bear no more than the weight of her son’s suffering and faints, supported by the pious women who rush to her aid. The latter, as distraught as the Virgin, are nevertheless consoled by Jesus, as Luke’s Gospel narrates: this is the moment depicted in the Chapel of the Pious Women, added at a later stage, and which we find while still proceeding to Mount Calvary. To reach it, we must travel up a slope that leads us first to the Chapel of Veronica, and then to the group of chapels on the summit. The Chapel of Christ’s Prison takes us inside a bare room, where Jesus is solitary, contrite, caught praying with his hands crossed on his chest, according to an iconography particularly in use among Franciscans. The next Calvary Chapel is one of the most engaging. From below, we enter theaedicule of the Stabat Mater and watch, moved, the crucifixion, along with St. John, Mary and the pious women: all the figures are facing Christ crucified, located above, visible through an opening. To get to the crucifixion floor, it is necessary to go up again: Christ with the two thieves are leaning against a wall where we see the entire crucifixion scene frescoed. On the floor and outside, we cannot help but notice a conspicuous crack: it is an allusion to the "rocks that broke" at the moment Christ breathed his last. The visit to Calvary ends with the Chapel of the Holy Sepulchre (we find inside the statues of Mary Magdalene, who went to the tomb of Jesus, and St. Helena, who, according to tradition, found the true cross of Jesus, while further down, in a room that is so intimate and narrow that anyone is forced to stoop to reach it, since the access door is little more than a meter high, we encounter the statue of Christ laid in the tomb: the fact that the place is so dark and cramped is due to the fact that the pilgrim was called to a moment of intimate recollection and intense prayer) and with the Chapel of the Noli me tangere, with the group assigned to Giovanni della Robbia and dedicated to the episode of the encounter between Magdalene and the risen Christ, who advised her not to hold him back any longer ("Noli me tangere," "Do not hold me back") because he had not yet ascended to heaven. Unfortunately, only the statue of Magdalene survives of the latter group.

|

| Crowning with Thorns. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Flagellation. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Ecce homo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Crucifix aedicule, detail. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The going to Calvary. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The figure of Jesus in the going to Calvary. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Chapel of the Spasimo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Spasimo. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Veronica. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Jesus in prison. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Wayside shrine of the Stabat Mater, the characters. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Wayside shrine of the Stabat Mater, detail of the Madonna. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Crucifixion. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Chapel of the Crucifixion with the fake crack on the outside. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Magdalene. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| St. Helena. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Jesus in the tomb. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Magdalene in the Noli me tangere group. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

We can then return toward the beginning of the itinerary: in the descent we first encounter the Chapel of St. James the Lesser (which, in the Brief of Leo X, was nevertheless referred to as the "Chapel of St. James the Greater"), inside which there is a statue of the saint, attributed to the Master of Bigallo. It is then the turn of the Chapel of the House of Caiaphas, inside which we can observe the scene with Jesus being led before Caiaphas, the incumbent high priest (Anna was no longer such, but had remained in the sanhedrin and retained his title) and the one with Jesus being mocked, both of which are of great impact for the visitor, who is almost intimidated by the extremely severe and impassive appearance of the high priest and the members of the sanhedrin.

Having gained the main road again, the visit ends with the last three chapels. The first two on the route are not part of the original plan, nor are they inspired by places actually present in the real Jerusalem: they are two oratories added in the seventeenth century, one dedicated to theAnnunciation, with a very simple group dating back to the nineteenth century, and the other having as its theme the Flight into Egypt, a further nineteenth-century chapel, with the group being the work of a local artist, Mariano Bondi, who left his signature on the base of the statue of the Madonna in 1836. We leave Jerusalem after visiting the last of the loci, the Chapel of the Ascension, which we find just before the provincial road. It is a small circular temple that houses inside it theAscension of Jesus, executed by Giovanni della Robbia and his collaborators, including his sons Marco, Lucantonio and Simone.

|

| The lesser St. James. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Christ Mocked. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| Christ before Caiaphas. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The chapels of the Flight into Egypt and the Annunciation. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Annunciation. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The flight into Egypt. Ph. Credit Finestre Sull’Arte |

|

| The Ascension. Ph. Credit Jerusalem of San Vivaldo |

The journey ends here: it is a journey that spans centuries of history, since, from the moment the first chapels were built and the first sculptural groups began to be installed inside them, pilgrims from all backgrounds came to these places with the specific purpose of completing the entire route. A path that no longer corresponds, unfortunately, to the one imagined by its creators: neglect and the centuries have erased a part of it, but that part is today carefully guarded and the subject of careful protection by the Superintendence, which in the 1970s subjected the complex to painstaking restoration. And still today, visitors leave the Jerusalem of San Vivaldo with a feeling of melancholy and emotion at the evil and inhuman scenes they directly witnessed, but with wonder at having visited one of the most beautiful places in Valdelsa and unique in Italy.

Reference bibliography

- Rosanna Caterina Proto Pisani, The Jerusalem of San Vivaldo, Polistampa, 2006 (reprinted 2014)

- Luciano Vaccaro, Francesca Ricardi, Sacri monti: devotion, art and culture in the Counter-Reformation, Jaca Book, 1992

- Sergio Gensini (ed.), The “Jerusalem” of San Vivaldo and the sacred mountains in Europe, Pacini Editore, 1986

- AA.VV., Religiosity and society in Valdelsa in the late Middle Ages, proceedings of the conference (Montaione, Complex of San Vivaldo, September 29, 1979), Historical Society of Valdelsa, 1980

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.