The Rosso di Montelupo, a masterpiece of a centuries-old ceramic tradition

When art is linked to its territory, it creates a series of connections that range from culture toeconomics, from history to the everyday life of an entire population; it becomes itself a testimony to a past that must be studied and deepened in order to know its roots and admire it with different eyes in the present. An example of this is one of the masterpieces, if not the masterpiece, of a museum deeply linked to its territory, the Museum of Ceramics of Montelupo Fiorentino: we are talking about the Rosso di Montelupo, the sum work of the activity most settled in this place, namely the production of ceramics.

Sinceprehistoric times, traces of ceramics have been witnessed in the settlements of the Middle Valdarno Fiorentino area: this highlights how the entire area has always been inextricably linked to ceramics and inevitably, in later centuries, to its production. In particular, the history of Montelupo Fiorentino, on the left bank of theArno River, allows us to understand the various epochs, as well as the various phases, of pottery production and all the economic and commercial aspects that followed over time. Certainly the Montelupese economy was supported by neighboring Florence since, relying on the growing production of ceramics, it had relied on the Florentine mercantile system in order to get its goods outside its territory. Especially following Florence’s conquest of Pisa, Montelupo had transformed its workshops into enterprises aimed at extra-regional exports: access to the sea was in this way favored by the Arno river route, through which Montelupese finished products reached the Pisan port and from there to Livorno. The overbearing Florentine determination had even crushed the intense production of Pisan majolica, which, by the mid-15th century, had been forced to turn to a new production so as not to create impediments to Florence: that of engobed pottery.

|

| Workshop of Lorenzo di Piero Sartori, Rosso di Montelupo (1509; glazed pottery, 38 x 9.5 x 4 cm; Montelupo Fiorentino, Museum of Ceramics) |

It was the task of the navicellai, those who carried out the boatman’s trade, which was widespread on the banks of the Arno River, to wait for Montelupese potters and trading companies, which had begun to form among potters and merchants, to embark and transport goods at rather cheap costs to the Pisa and Livorno docks. From these latter ports Montelupo ceramics were again embarked on ships that sailed across the entire Tyrrhenian Sea to Sicily and even to the Mediterranean East. Montelupo’s economic fortunes, which occurred especially from the first half of the fifteenth century onward, were thus due to the opening of seaports, the waning of Pisan majolica production, and the use of merchant capital. A real turning point: from a simple “walled land,” Montelupo Fiorentino had become a privileged center of production for the dominant Florence.

Written records testify that in the second half of the 15th century Florentine capital was being employed in Montelupese ceramic enterprises. To gain a better understanding of what the proportions of the channels for the diffusion of Montelupese majolica were at the end of the 15th century, in a notarial deed of 1490 stipulated between Francesco Antinori and twenty-three master potters of Montelupo we read that Antinori was to undertake to purchase for a period of three years, at agreed prices for three different types, the entire ceramic production of those who had intervened in the deed and their relatives; in return the twenty-three potters were to work for these three years exclusively for Francesco Antinori.

The expansion of Montelupese products is even attested at archaeological sites in London, Southampton, and Amsterdam. However, the peak of Montelupese ceramic activity was reached between 1480 and 1510, a period in which we witness the birth of a new language, that of the Renaissance, characterized by a strong pictorial realism and accentuated polychromy. From the strict monochromatic blue color scheme, with which diluted cobalt blue allows glimpses of white enamel in the backgrounds, typical of the Islamic-influenced decorative style, there is a shift to a gradually richer chromaticism: pale copper-green, manganese with violet tones, and citrine yellow are added, or what Gaetano Ballardini, a distinguished scholar of ceramics, called the “cold palette,” and later, coinciding with theemergence of the new language of the Renaissance, a red pigment was added, hitherto unseen in Italy, presumably obtained from the same raw material with which the potters of Ä°znik (ancient Nicaea, Turkey) made the samplings of a relief tone of red, lacquered and sanguine, as well as strongly brilliant. The latter raw material arrived in small quantities at the Valdarno kilns from the same Florentine companies that by then traded Montelupese majolica and was used only in the case of repasses, highlights and portions of coats of arms. Case in point for Montelupese Rosso, where a considerable amount of this particular pigment can be seen.

We can define these three phases of monochrome, cold palette and polychrome as the three major phases of both chronological and formal development of the so-called damask, considered the genre in which we witness in full terms the decorative influence of Islamic matrix in the production of painting and ceramics. Although, however, the first two phases explicate the true development of the genre, while the polychrome phase, although related to it, now underscores its pressing outgrowth.

Moreover, from the depiction of phytomorphic, zoomorphic and even human figures, from the depiction of sumptuously dressed horses and falconers, from the depiction of young men engaged in the exchange of sweet amorous effusions in gardens of delight and from the symbolism of virtue showing the affirmation of international Gothic, we come to an extreme realism with figures to which values and functions are attributed. Figures, coats of arms and symbols stand out in the center of the ceramics and are divided from the marginal parts often by a stylized garland. There is thus a development of the tendency to exalt the main subjects, represented realistically, and to seek an appropriate graphic frame as a contour to the central figures, with the belief that not only the main figure but also the surrounding space contributes to the expression of this desired realism. Parsley and vine leaves, the floral, the eye of the peacock feather, the Persian palmette, interwoven ribbons, ovals and rhombuses are among the main outline motifs found on the ceramics. And it was during the first twenty years of the sixteenth century that Montelupese ceramists put themselves excellently to the test, with excellent results, copying from life the Oriental prototypes, depicting the large poppy flowers in monochrome blue from China and the oriental knots woven and luminized with the use of graffitura, and approaching the Ä°znik ceramics characterized by that bright, blood-red pigment, such as Montelupese Red.

|

| Monochrome damask basin (c. 1440-1460; faience; Montelupo Fiorentino, Museum of Ceramics) |

|

| Peacock feather eye dish (c. 1500-1510; faience; Montelupo Fiorentino, Museo della Ceramica) |

|

| Dish with ovals and diamonds (c. 1500-1510; faience; Montelupo Fiorentino, Museo della Ceramica) |

|

| Dish with blue graffito band (c. 1510-1520; majolica; Montelupo Fiorentino, Museo della Ceramica) |

All this knowledge about the various stages of working techniques and the different types of decoration in Montelupo ceramics stems from an extraordinary discovery made in 1973, a year that marked a real turning point in terms of our knowledge of the history of Montelupese clay activity. During a simple urban redevelopment project in the area of the town known as “del castello,” where the first settlement of considerable size had sprung up on the hill of Montelupo, so as to form a sort of walled castle, a number of public wash houses had been discovered that were used in the past by the residents of that area. According to the municipality’s plan, these were to be demolished in order to build a small square at that spot, which would begin a work of urban renewal and decorum. One of these, however, which was large in size, turned out to be a treasure: inside it was kept a huge quantity of fragments of majolica tiles of various types. Faced with such a discovery it was impossible to remain indifferent, to cover it up and not be aware of the richness of those fragments, evidence of the history of ceramic production in that area.

Therefore, the so-called “washing well,” as the precious well found was called, was the subject for the duration of about two years of a real exploration of its interior by emptying it to a depth of about two meters. What for the residents of the past constituted a large furnace drain, in 1973 and the years immediately following, represented an extraordinary historical record to begin collecting, analyzing and studying. The in-depth study of these finds, supported by a comprehensive knowledge of the pottery, was able to lead to an understanding of the fictile trade flows and the dating of the archaeological deposits.

With the discovery of the “pozzo dei lavatoi,” Montelupo Fiorentino was introduced to medieval archaeology, which, in the very same year, had been officially born in Italy with the publication of the two-volume work Storia della maiolica di Firenze e del Contado written by Galeazzo Cora: a wide audience of scholars and even readers had become interested in the history of Florentine majolica in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.

As a result of the wise decision to have the artifacts found remain in the Montelupo area and to consolidate that research and restoration activity that had been created around the majolica fragments of the washhouse well thanks also to the establishment of the “Archaeological Group of Montelupo,” it had come to the inauguration in 1983 of the first Museum of Ceramics and the Territory, set up in the former mayor’s palace of Montelupo, divided into only four rooms that housed a scarce collection of fragments. Thanks to unrelenting research, it had become necessary to move to the large building of the former elementary school in Montelupo, in which, as of May 24, 2008, the new and present-day Museum of Ceramics is being unfolded. Today more than a thousand ceramics are on display here, but it could be said that the continuous research activity bears fruit almost daily, thus constantly enriching the collections already present.

|

| The facade of the Museum of Ceramics in Montelupo |

|

| A room of the Museum of Ceramics of Montelupo |

|

| A room of the Museum of Ceramics of Montelupo |

|

| A room of the Museum of Ceramics of Montelupo |

A de facto museum consisting mostly of archaeological artifacts from the recovery of materials taken from the discharges of local kilns in the historic center of Montelupo. Walking through the exhibition halls of the Museum of Ceramics is a journey of discovery of the oldest and most productive activity of the place, rooted in this territory for centuries and centuries. As a succession of all the collections preserved here, arranged in special showcases subdivided by chronology and by theme, unfolds before your eyes, you cannot help but be enraptured by so much beauty and craftsmanship, by the various designs and figures that with great skill have been imprinted on the shining majolica, and reflect on how much time has passed since their creation, almost impossible to believe because of the state of preservation in which they are found.

They range from the earliest archaic majolica to sapphire, from damask to robbiano blue majolica, from engobe and graffito to metallic luster. And again all the different decorations, from the simplest to the most elaborate, adorning the most varied objects such as basins, tankards, apothecary jugs, bowls, and plates: Valencian leaves, parsley leaves, bands, peacock feather eyes, Persian palmettes, floral decorations, ribbons, coats of arms and trophies, garlands and grotesques, and oriental knots.

In addition to these, it is fun during the visit to recognize the animals, plants, female and male figures depicted, suns and moons, cupids, as well as landscape, mythological or scenes that refer to the everyday life of that time. It is a bit more complicated to recognize the coats of arms belonging to the different families, but it is sufficient to read the ever-present captions related to each object on display. A very valuable aid to the visit is provided by large explanatory panels that mark each sector of the museum and make the exploration of this museum site understandable to all visitors, whether they are adults, children or foreigners.

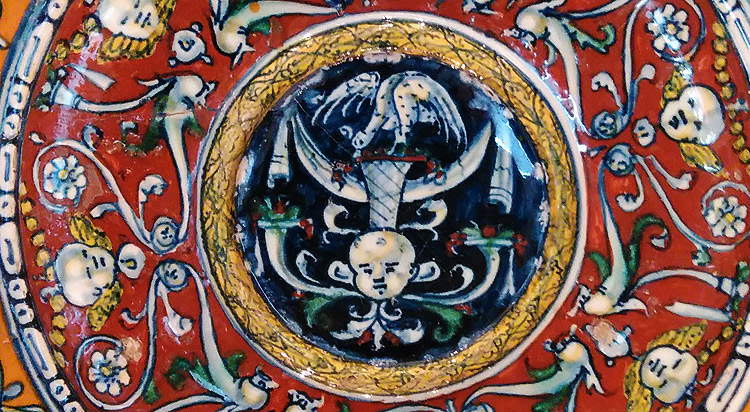

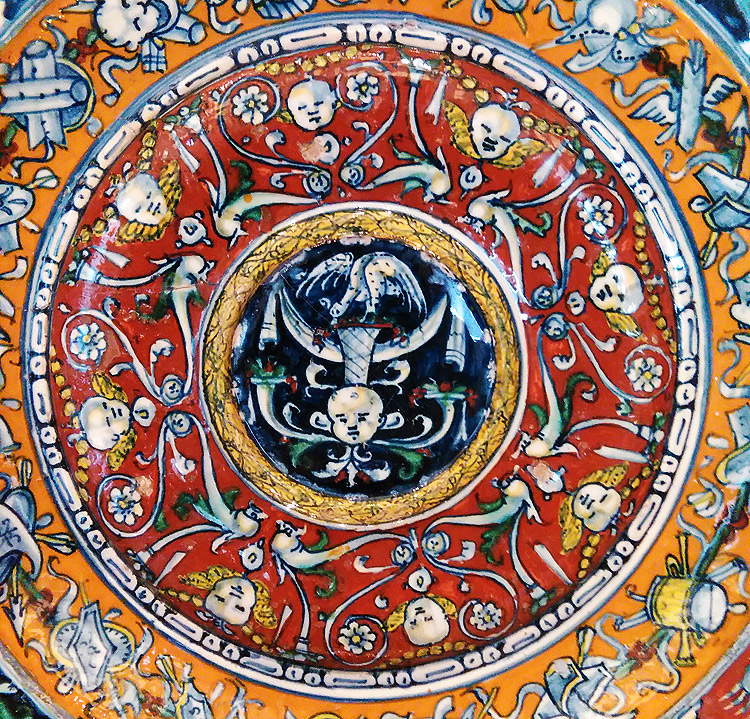

However, the work that more than any other on display here provokes reactions of wonder and amazement whenever one encounters it and inevitably pauses to admire it in all its beauty is precisely the so-called Red of Montelupo, a work-symbol of the museum, to which almost an entire room is dedicated. It is a medium-brim flat basin, with a diameter of 38 centimeters, made in 1509 in the workshop of Lorenzo di Piero Sartori, one of the most significant and active Montelupese workshops, very productive in the Renaissance period, characterized by the initials “Lo” on its products.

|

| The Rosso di Montelupo in its room at the Museum of Ceramics. |

Its name is due to that red pigment-the color that immediately jumps out at the eye-mentioned earlier, which refers to the precious and stupendous Ä°znik majolica, which by the effect of fire becomes a blood red and lacquered. Local artisans used it in third firing in small quantities, but in the case of Montelupo Red one can see extensive use of such a pigment, a trait that makes it very vivid and pleasing to the eye.

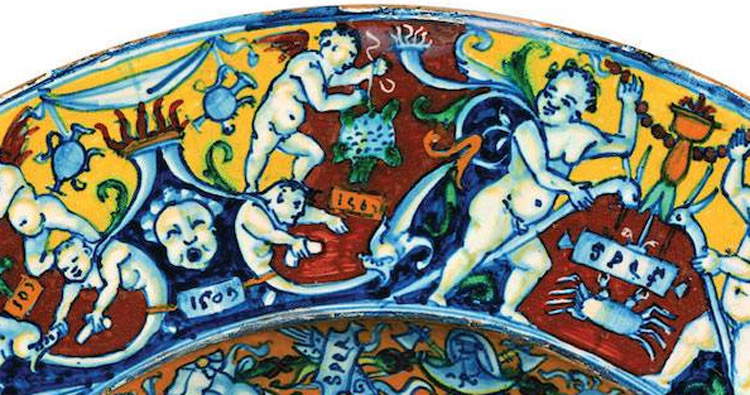

In the center of the basin, enclosed by a golden garland, is a kind of cameo of blue color within which is depicted a small putto’s head between two cornucopias, on which appears a basket of fruit on which rests a large bird. This is followed by a part on a red background decorated in a grotesque pattern depicting putti heads, small flowers and strings of pearls. The next part with an orange background, called “ricasco,” which is the area where the brim and bottom of the basin join, is decorated with a trophy band consisting of shields, armor, weapons, drums, and lion heads, and two plaques on which the inscription SPQR appears.

Much more elaborate is the brim of the work, ornamented following two different compositions that alternate with each other. One consists of a pair of putti: both hold a string of pearls with one hand and with the other hand a kind of staff that has a dolphin’s head on top. Between the two putti, the space is divided horizontally into two parts: in the lower, red-colored one, a crab is depicted holding a plaque with its claws, on which appears the inscription SPQR or, in some cases, SPQF, referring the latter to the Florentine people; in the upper, yellow-colored section, a stylized vase stands from which the string of pearls held by the two putti departs. The other composition of the brim consists of a pearl-like head on a blue background that appears to be emitting a cry: under this appears a plaque on which is inscribed the date 1509, the year the entire basin was made, while in the upper section sampled in yellow are depicted trophies and ribbons.

|

| The decoration in the center of the bottom of the Rosso di Montelupo |

|

| The decoration in the center of the bottom of the Rosso di Montelupo |

|

| The decoration on the brim. Note the date 1509 |

|

| The decoration of the embroidery |

|

| The back |

It could be said, then, that the masterpiece completed in Sartori’s kiln is an unparalleled combination of grotesque decoration, for the realization of which the most varied compositions and elements, including celebratory ones, were used, and of backgrounds in different colors, such as deep blue, orange, yellow and, of course, the bright, blood red to which the work is named and whose composition still remains mysterious. Although it is thought to be arsenic-rich manganese oxide imported from Anatolia.

The grotesque decoration on an orange background would create a connection with Sienese production of that period, as the Sienese were wont to use grotesques, figures with dolphins, and red and yellow backgrounds, but there is no doubt that the Rosso di Montelupo is a product of the Sartori kiln, one of the most illustrious and renowned Montelupese potters, not only because of the unmistakable initials “Lo” on the back, but also because of the discovery of fragments with grotesque decoration on yellow and orange backgrounds made by Sartori himself and found in the drain of his kiln. The shape of the basin itself was a novelty for the time: it was a new, unusual shape, even though Sartori had been inspired in part by the basins of aquarelle and metal used to collect the water that came down from the pitcher for washing hands.

The famous basin was part of the collection of the Rothschilds of Paris, an important family of art and antiquities collectors and patrons for generations and generations; it belonged precisely to Gustave de Rothschild, a Parisian banker who died in 1912. From Gustave’s heirs, the basin had later passed to another Parisian collector, antiquarian Alain Moatti, from whom the City of Montelupo purchased it in 2002 with the specific intention of donating it to the museum. Now it can be contemplated in the Montelupo Museum of Ceramics: from Paris the precious work has proudly returned to its homeland. Admiring the Montelupo Red is an exaltation of sight and a tribute to the most productively and qualitatively rich and intense era in the history of Montelupo ceramics, as well as to one of the most prominent workshops of the time.

Reference bibliography

- Antonio Fornaciari, The substance of forms: morphology and chronotypology of Montelupo Fiorentino majolica, All’Insegna del Giglio, 2016

- Fausto Berti, The Museum of Ceramics in Montelupo, Edizioni Polistampa, 2008

- Fausto Berti, Notes on the archaic majolica of Montelupo Fiorentino in Archeologia Medievale, IX (1982), pp. 175-191

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.