The great absentee in art history is the famous Battle of Anghiari commissioned from Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519) to decorate one of the walls of the Salone del Maggior Consiglio, now the Salone del Cinquecento, in the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence, a work that was never completed in its entirety. The Tuscan genius worked on this wall work from 1503 to 1506, producing, however, only a few drawings and studies, a preparatory cartoon, and going so far as to paint only the central group, thus leaving the work unfinished since the painting failed in a short time and all traces of it disappeared within a few decades, when Giorgio Vasari (Arezzo, 1511 - Florence, 1574) architecturally and pictorially rearranged the room that housed it.

Some might object that no less weight and fascination is also held by the other unfinished work, designed as a pendant for Leonardo’s, namely the Battle of Cascina entrusted to Michelangelo. But while it is true that both works had great resonance with contemporaries and posterity, the sense of loss with Leonardo’s work seems more vivid, primarily because Michelangelo never got ever beyond the preparation of the drawings and cartoons (although it must be taken into account that not a few scholars doubt that even Leonardo had ever arrived at the masonry realization), and secondly because of the Caprese-born artist important frescoes are still preserved, including the masterpiece cycle in the Sistine Chapel, while on the contrary Leonardo’sLast Supper looks hopelessly worn out.

Meagre consolation is that we can have a faint idea of what the scene painted by Leonardo, namely the one with the Dispute for the Standard, the only group made, must have looked like, thanks to the splendid autograph drawings, and to a drawing preserved at the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which some have wanted to identify as the last fragment of the monumental cartoon, later reworked, prepared by the artist at the Pope’s Hall in Santa Maria Novella.

To date, not only a number of pictorial copies of the Battle are known, but also several graphic works. The scene, famous therefore thanks to replicas and presented with some variations over time, shows four knights vying for possession of the banner and its pole, in a heated battle. From left to right, one should distinguish Francesco Piccinino and his father Niccolò, Perugian commanders of the army in the pay of the Milanese Visconti, and Ludovico Scarampo and Pietro Giampaolo Orsini, the former an admiral of the papal troops allied with the Florentine army, led by the latter. At their feet three foot soldiers are also caught up in the raging battle, kneeling, one of them trying to pull himself to safety with his shield, while two others are desperately struggling.

These are elements that recur continuously, while there are some divergences present from copy to copy for which it is difficult to trace the reasons. Perhaps they are attributable to the different source of inspiration, the wall painting itself, the cartoon, or the even more debated preparatory panel; or rather more simply over time some artists introduced their own inventions.

Drawings and prints had the not insignificant advantage of being easily transportable and more cheaply traded than oil paintings, and for that reason they served for a long period of art history as one of the main mediums for artists to learn about types and models and to keep themselves constantly updated.

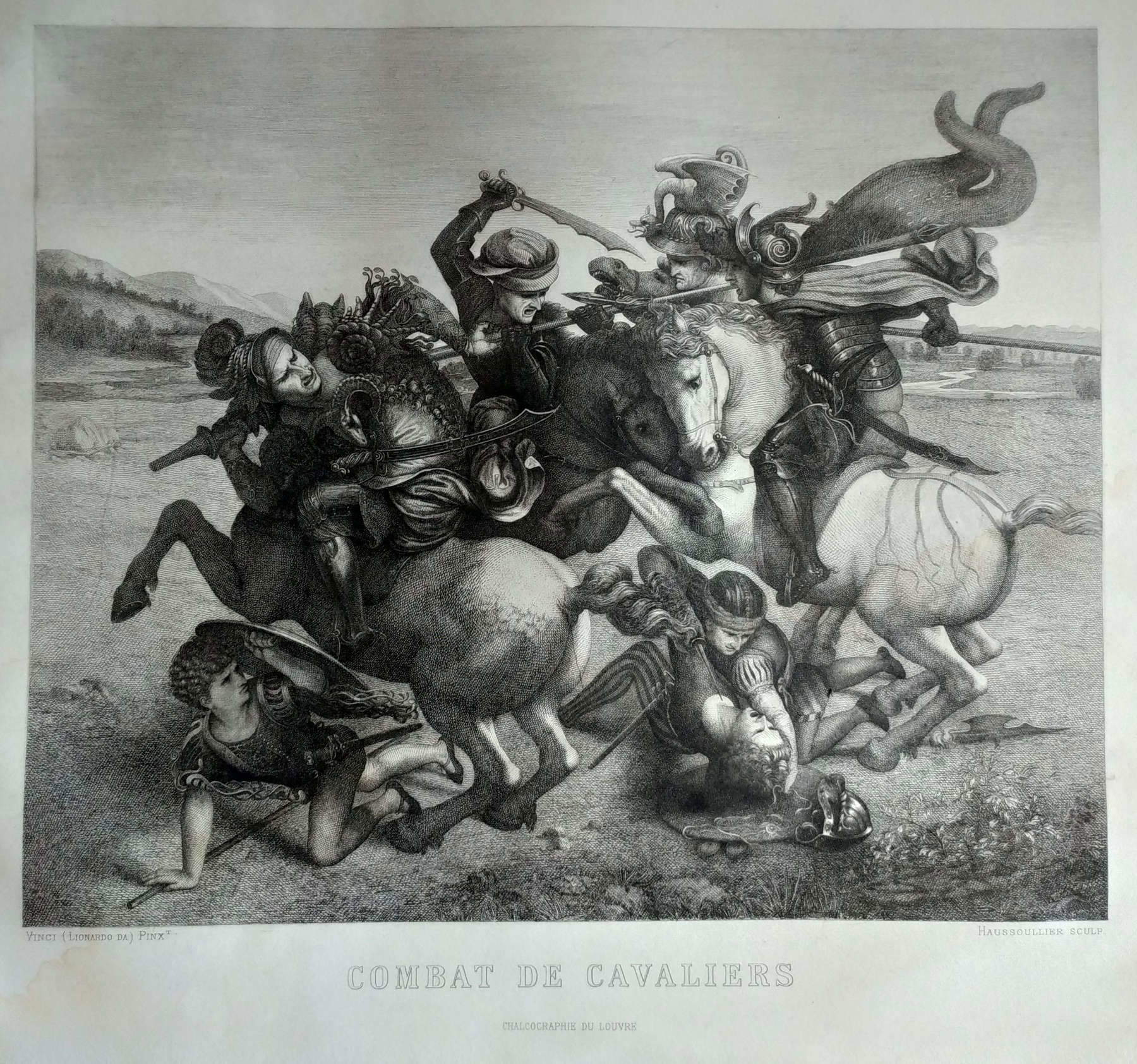

The most famous and cited account of the Battle is the drawing now in the Louvre, made by Pieter Paul Rubens (Siegen, 1577 - Antwerp, 1640) by reworking an older drawing, probably from the 16th century. It was not uncommon for the painter to buy drawings from the past and modify them in his own way, with white lead and pen for example, and adapt them to Baroque taste. After all, by the time Rubens arrived in Italy, neither the mural nor Leonardo’s cartoon existed. According to a number of critics, including Vincenzo Farinella, this is the most effective account of the Battle because it is the one that best captures “this irrepressible outburst of violence that overwhelms all the figures, and creates a sort of monstrous knot in which heads, paws, faces, arms and weapons come together in an almost inextricable way.” Unlike painted panels known to us such as the Palazzo Vecchio panel, the Doria panel, or the Horne Museum copy, where a single knight wields a sword, in Rubens’ work the two mounted condottieri cross arms.

Of even easier circulation and therefore more adaptable to promoting awareness of the Banner Fight were printed engravings, which could be pulled in multiples and therefore reach a larger number of people. Among these, perhaps one of the most significant was the engraving by Lucchese artist Lorenzo Zacchia (Lucca, 1524 - after 1587), a specimen of which is preserved in the Albertina in Vienna.

The painter made the graphic in 1558, and thus before Vasari intervened on the room that housed Leonardo’s Battle, so it is still debated today whether it is a translation from the original mural, from the cartoon, or from a preparatory painting by Leonardo to which the inscription in the margin of the engraving that speaks of “a former table” painted by Leonardo’s hand would allude. This graphic is denoted in its uniqueness as one of the combatants is about to hover an axe blow.

Many engravings are now preserved at the Museum of the Battle and Anghiari, where an interesting nucleus of works attesting to the graphic fortunes of Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari is housed. Great importance for the success of Leonardo’s iconography should be attributed to the beautiful engraving by burin, preserved right at the Anghiari Museum, known as The Struggle of Horsemen from Leonardo da Vinci’s Battle of Anghiari made by Gérard Edelinck (Antwerp, 1640 - Paris, 1707) between 1657 and 1666, and a mirror of Rubens’ famous drawing. The artist, who was court engraver during the reign of Louis XIV of France, revitalized the Leonardo archetype at a time when Europe was emerging from the Thirty Years’ War, thus encountering a particularly fruitful season for depicting battle scenes.

A specimen of the sheet, as well as other graphics that testify to the widespread dissemination of Leonardo’s masterpiece, are also kept at the Museum of the Battle of Anghiari, in the town of the same name, an institution that also serves as a center for in-depth study of Leonardo’s vanished work.

Another famous replica is the etching by Antonio Fedi and Matteo Carboni, dated 1791 and included in the printed volume L’Etruria Pittrice Ovvero Storia Della Pittura Toscana Dedotta Dai Suoi Monumenti Che Si Esibiscono In Stampa Dal Secolo X. Fino Al Presente, which aimed to collect replicas of the most representative works of the Tuscan masters. The graphics, although of poor quality (both infantrymen and horsemen are in fact delineated in a grotesque manner and the “terribleness” of the original work is dissipated), also had a strong echo in promoting Leonardo’s idea. Rather rare case, however, is the circa 1880 etching by Frenchman William Haussoullier (Paris, 1815 - 1892), which replicates a lesser-known and less accessible copy even today, and known as the Timbal copy, named after the artist who collected it.

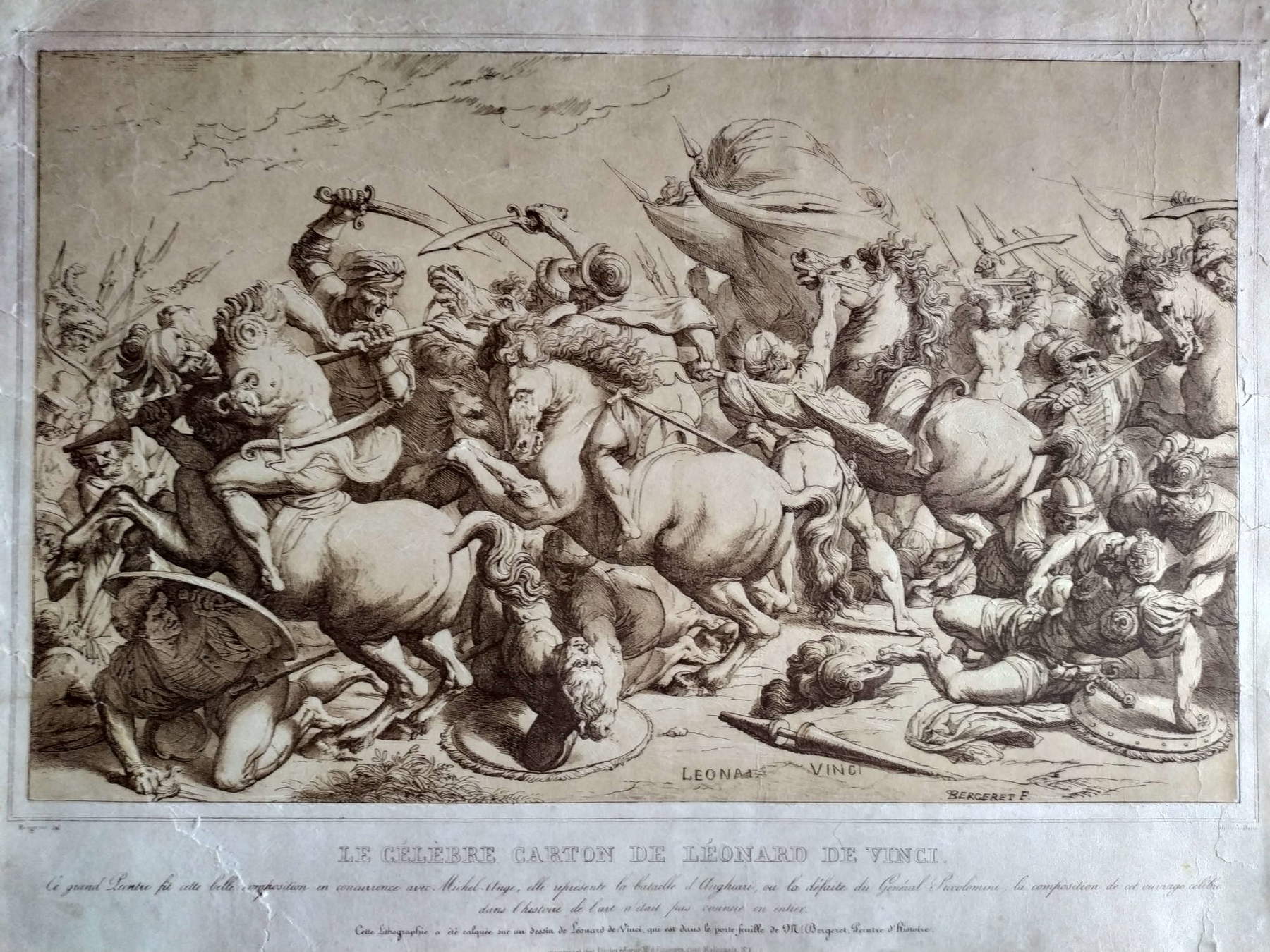

Still other artists did not shy away from integrating the “Banner group” into a larger context, the result of invention or of more or less philological studies, as is the case with the lithograph by Pierre-Nolasque Bergeret (Bordeaux, 1782 - Paris, 1863), who immerses the Dispute group in a battle scene of redundant and stereotyped taste.

The graphics circulated quickly and spread throughout Europe, playing a major function in the knowledge of Leonardo’s battle iconographies, more so than pictorial replicas, which were often difficult to access, or mostly unknown until recent times, could guarantee.

They thus ensured, an almost interrupted fortune for Leonardo’s famous masterpiece, which from the past, passing through Delacroix’s Zuffa of Horses in a Stable or De Chirico’s works, until today, does not cease to fascinate and to make people talk about it.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.