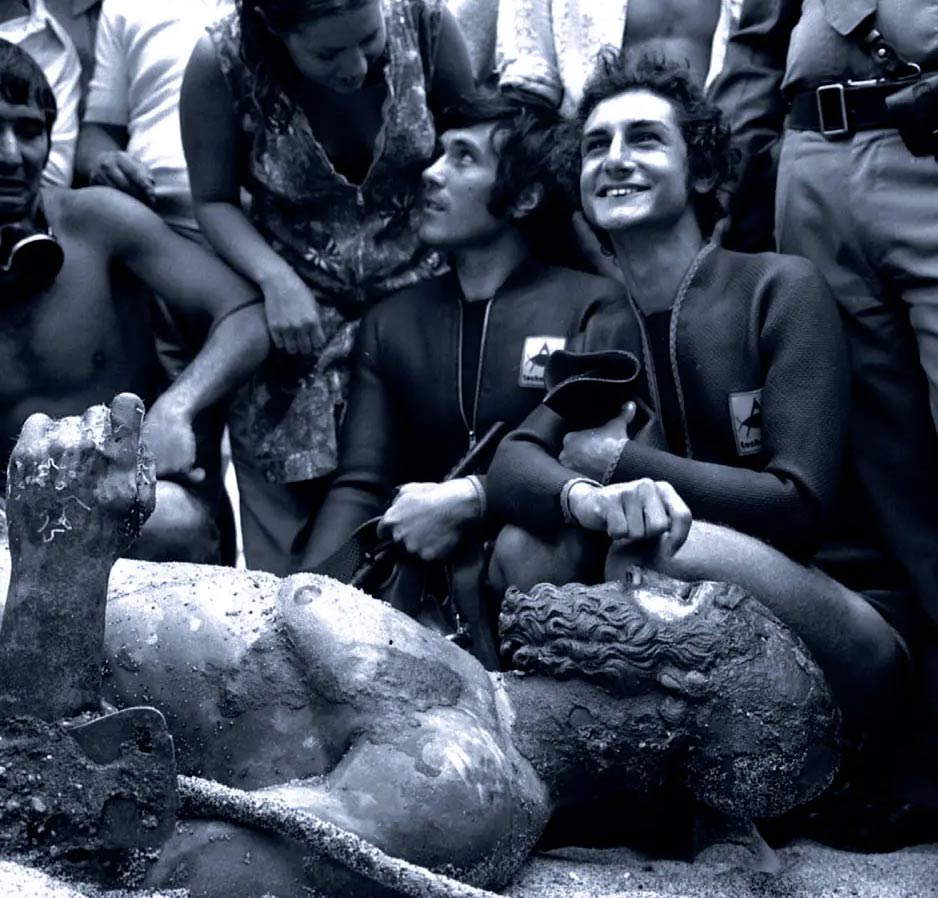

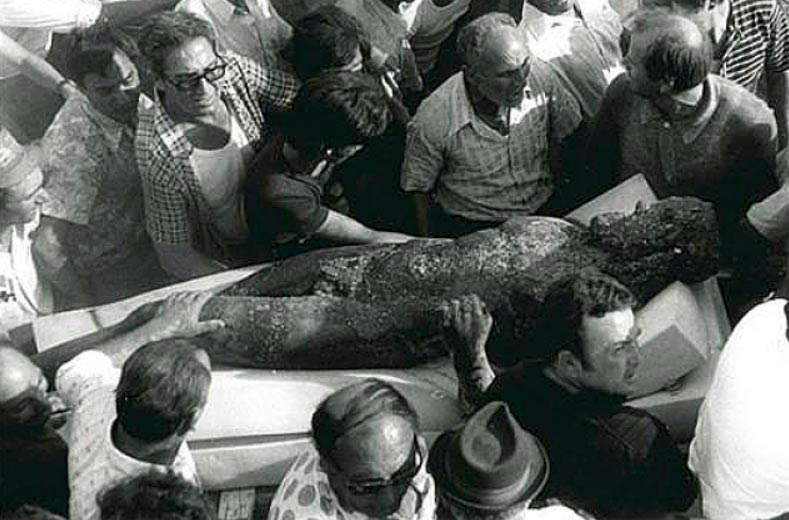

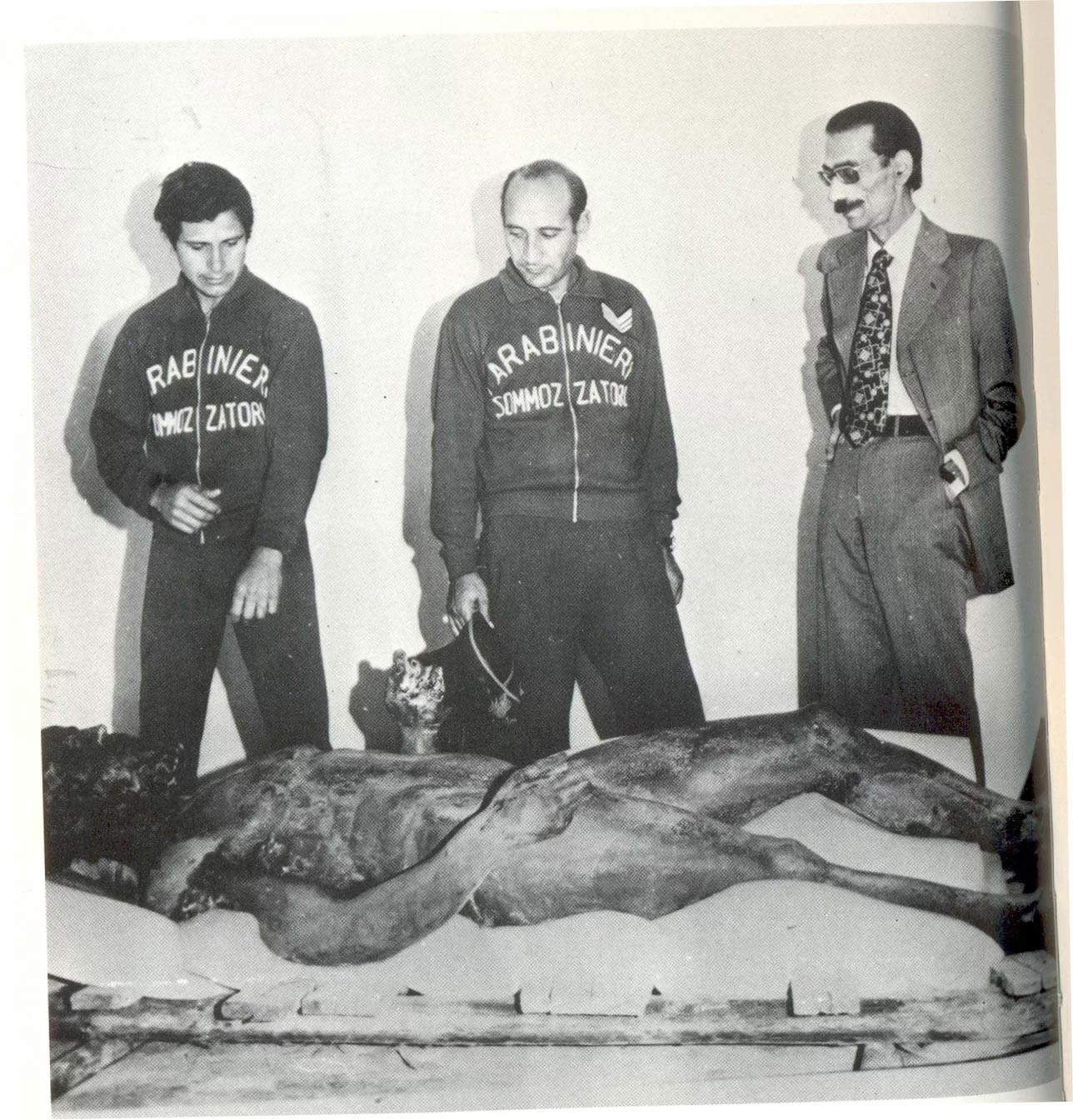

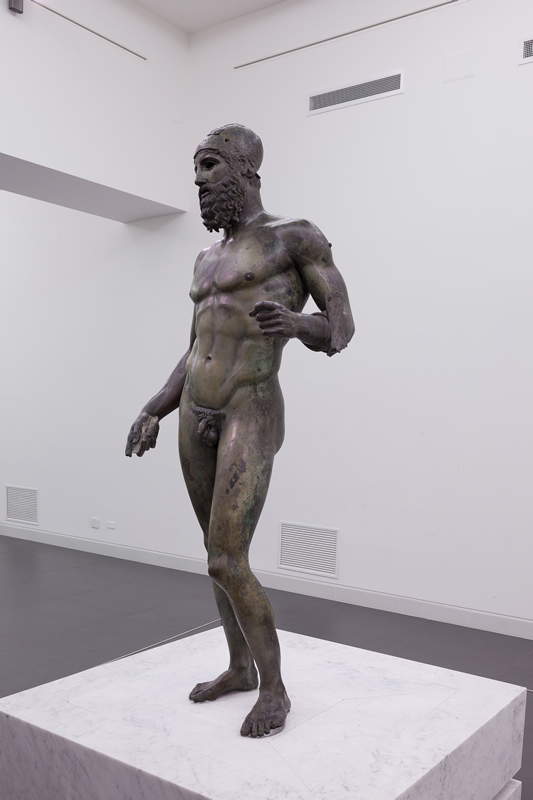

The extraordinary story of the Riace Bronzes, the two sculptures of Greek origin, dated to the fifth century B.C. and now housed at the National Archaeological Museum in Reggio Calabria, began on August 16, 1972: on that day, the young Roman amateur diver Stefano Mariottini, who was spending a vacation in Calabria, reported the presence of a statue sticking out of the seabed at Porto Franticchio, in Riace Marina, at a distance of about two hundred meters from the coast and at a depth of eight. The Centro Subacquei dei Carabinieri proceeded with recovery operations, which were conducted over the next few days under difficult conditions and in a far from exemplary manner (it was necessary to hurry because news of the find had spread): on August 21 Bronze B was recovered, while on the 22nd it was the turn of Bronze A. In the official report, which was filed with the Superintendency on August 17, 1972, the two statues were presented in this way: “they represent naked male figures, one lying on its back, with face covered with flowing, curly beard, arms outstretched and with one leg over the other. The other statue appears to be lying on its side with one leg folded and has a shield on its left arm. The statues are dark brown except for some lighter parts; they are perfectly preserved, cleanly modeled, with no obvious encrustations. The dimensions are approximately 180 cm.”

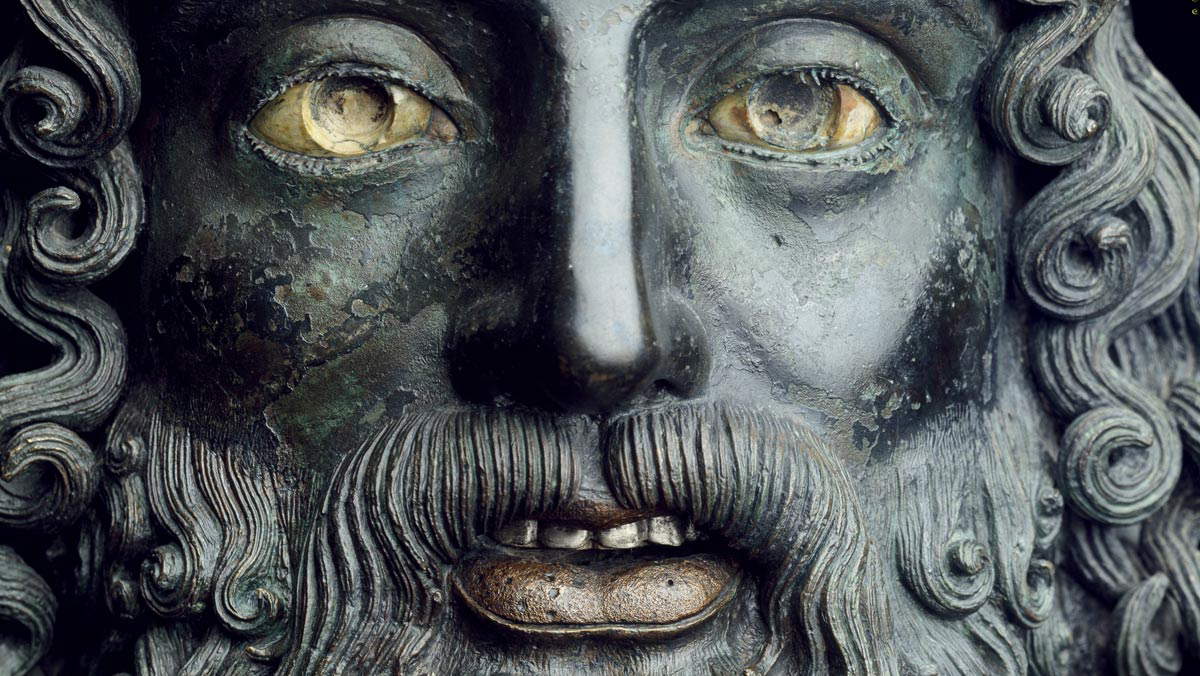

The statues were intact, but they were covered with marine concretions, so an initial cleaning operation was necessary to better read the works.The operation was carried out at the National Museum of Reggio Calabria, after which the Riace Bronzes were transferred to Florence, where they underwent a new restoration in the laboratories of theOpificio delle Pietre Dure, carried out by Renzo Giachetti and Edilberto Formigli. Only one year was needed to finish the cleaning, while the overall restoration took a full five years. Thanks to this intervention, it was possible to acquire several important pieces of information: for example, the fact that the bronze alloy had been obtained with two different combinations in the two statues, that silver, ivory and other precious materials had been used to highlight certain details, and that some of the soldering had been done at different times. Also, for Bronze B the casting took place in a larger number of castings than were needed for Bronze A.

Eventually, the two statues were ready to be displayed to the public, who were able to see them for the first time in a very successful exhibition (it drew about four hundred thousand visitors) at the National Archaeological Museum in Florence from December 15, 1980, to June 24, 1981. After another brief exhibition held in Rome, at the Quirinale, from June 29 to July 12, 1981, strongly desired by then President of the Republic Sandro Pertini, the two sculptures were able to return to Reggio Calabria to be displayed at the National Archaeological Museum. There were then other interventions, one between 1984 and 1987 and one between 1992 and 1995: on the latter occasion, in particular, the statues were partially emptied of the casting earth, that is, the material that had been used to shape them. After a new restoration in 2009-2011, the two statues were equipped in 2013 with anti-seismic bases made of Carrara marble and designed by engineer Gerardo De Canio in order to isolate the statues from both horizontal and vertical stresses (inside the bases are some caps in which four spheres also made of marble were inserted, which perform the anti-seismic function by absorbing the stresses, with the help of some elements that srv to dissipate the oscillations). Since then, the public has returned to admire them in the room, with filtered and controlled access, dedicated to them inside the museum in Reggio Calabria.

The recovery of the Riace Bronzes

The recovery of the Riace Bronzes The recovery of the

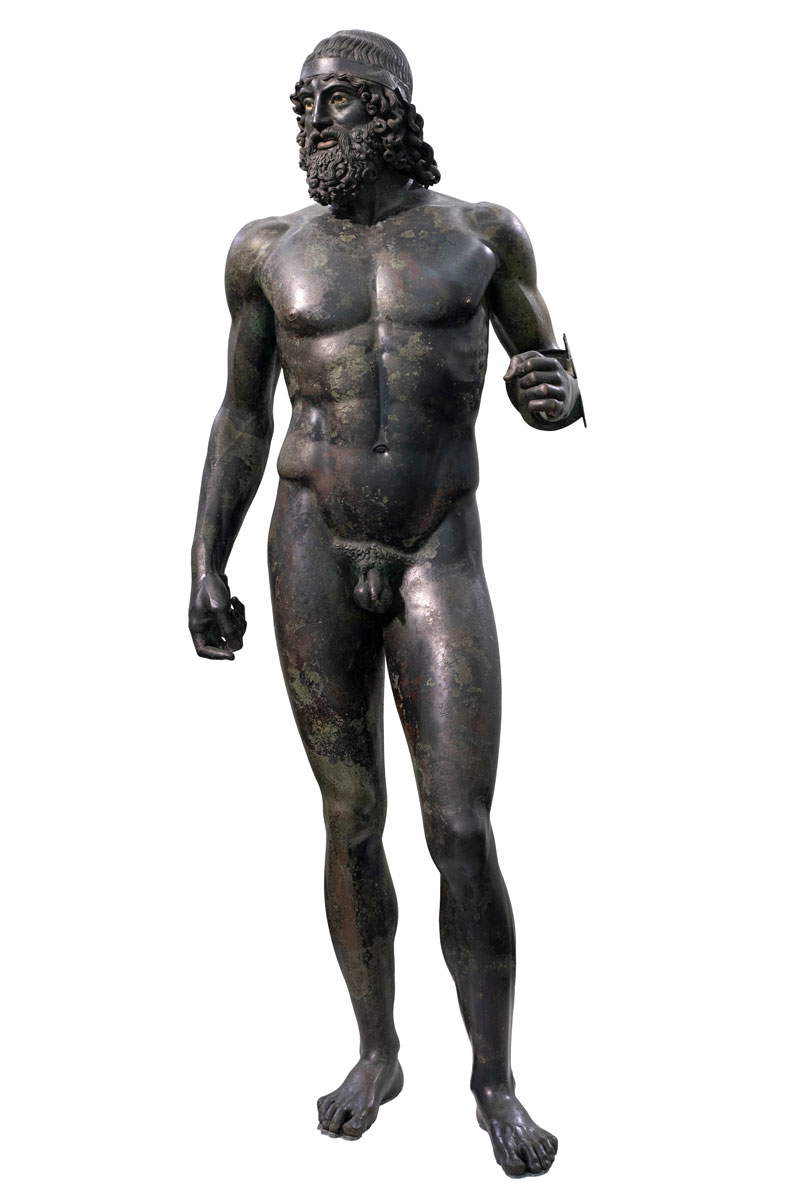

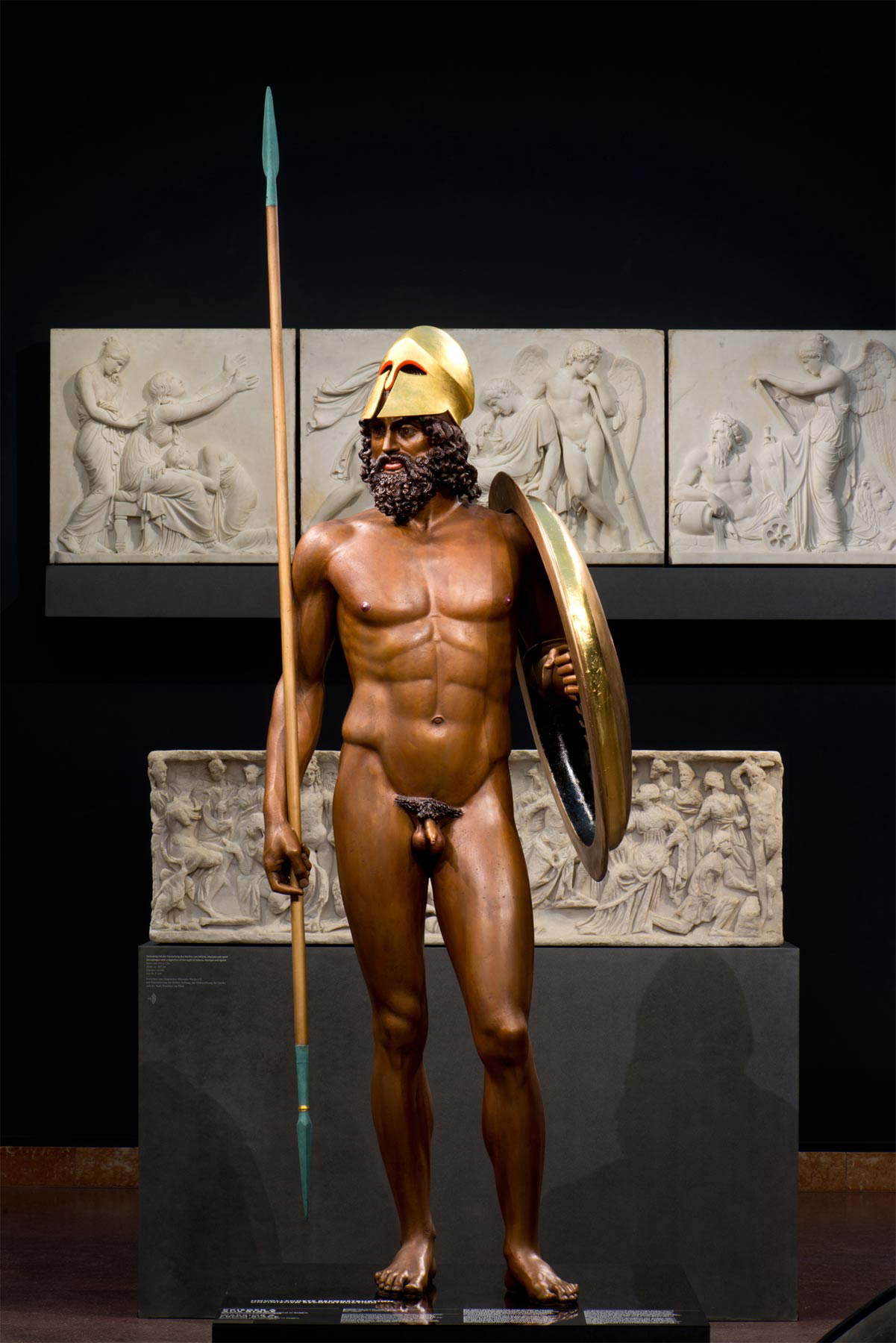

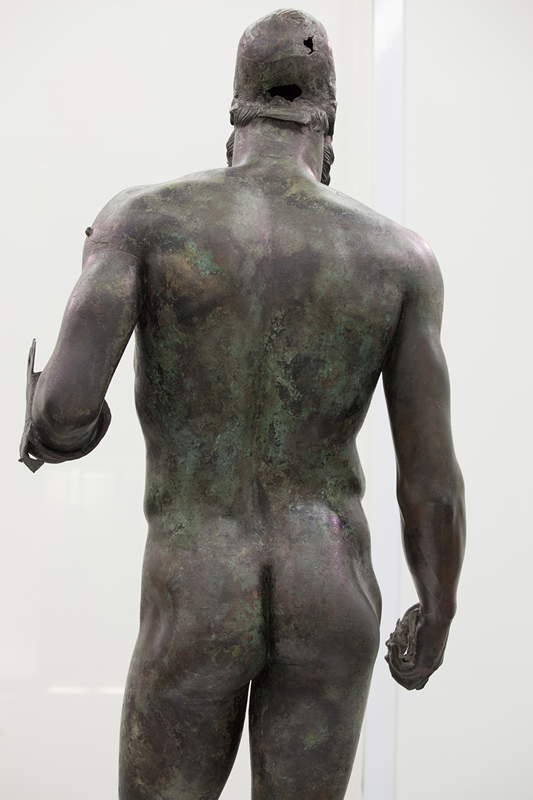

The recovery of theThe Riace Bronzes, 198 and 197 centimeters tall respectively and weighing approximately 160 kilograms each, depict two men with beards and curly hair, completely naked, with athletic bodies with well-defined muscles, lips that, in the case of Bronze A, open to reveal teeth, a serious expression, and in the same pose: they have their right arm stretched out along their side, their left arm bent at chest level, and they are presented in contraposto, that is, with the left leg (the one opposite the resting arm) advancing, and the weight being unloaded onto the right one, outstretched. Bronze B wears a cap, in Greek kyne, qualifying him as a king or strategist. Not only that, in ancient times the two statues wore a helmet, and were presented with a spear or sword in the right hand and a shield on the left arm, elements that have been lost. They are made entirely of bronze, except for a few details: Bronze A has teeth made of silver, the nipples of both statues are made of copper, as are the lips and eyelashes, while the eyes are made of white calcite, the irises (which have been lost) were anciently made of glass, and the lacrimal gland is of a pink stone. Originally, the two works were certainly colored.

Almost all scholars agree that the Riace Bronzes are two masterpieces of the severe style, that is, that transitional phase of Greek sculpture from the mature Archaic style to full Classicism, which can be placed in a period from 480 to 450 BCE.: the statues of this historical period (the most famous of which is probably the Chronides of Cape Artemisius now in the National Archaeological Museum in Athens) are presented with slender proportions, a more credible than that of the Archaic style, careful treatment of anatomical details, an equally truthful rendering of beards and hair, a certain simplicity (or severity, hence the name by which this style has been conventionally identified) of forms, an interest in movement, and a more pronounced individual characterization of the figures.

The main differences between the two sculptures can be seen in the faces: that of Bronze A (also called The Young Man or The Hero) appears much more tense, while the face of Bronze B (nicknamed The Old Man or The Strategist) is more placid. It is precisely this stylistic divergence (stiffer the A statue, softer its companion) that has led some scholars to think that there is a certain time gap of about thirty years between the two works. Otherwise, the two sculptures appear very similar, a circumstance that in the past has led to the assumption that a single hand was behind the two works (today, however, they are assigned to two different workshops). In order to reconstruct their history and try to define their identity, it is necessary to start from some fixed points, summarized as follows by scholar Ludovico Rebaudo: “they come from the same secondary context; they have the same dimensions; they represent the same general subject according to the same scheme, except for variations in detail; they are similar but not identical from a technical point of view; they are different from a stylistic point of view; the melting earths come from the same geological basin but from different microenvironments; the copper used in the casting alloys comes from the Mediterranean basin, but from regions far apart; the lead in the tenons securing the bases comes from the same deposit; carbon dating14 of the organic components of the cores places the execution of the statues in the 5th century BCE.C., with no possibility of further refinement.” It follows that any solution proposed to solve one or more of the problems concerning the Riace Bronzes must necessarily be compatible with all these points.

Initial analyses of some small samples of the casting soils found within the statues seemed to be compatible with the area of the city of Argos, in the Peloponnese, for Bronze A, and with the territory ofAttica for Bronze B.It had therefore been suggested that the first sculpture had been made by an Argivian artist, and the second by an Athenian (Professor Paolo Moreno had advanced the names of the sculptors Ageladas and Alkamenes), who probably collaborated in their execution with a view to the creation of a single monument, working, however, separately, in their workshops. A more in-depth analysis of the materials, conducted during the intervention at the Central Institute for Restoration in Rome in 1995, led to more refined results: it was thus found that “the substantial identity in the percentages of oxides the substantial identity in the percentages of oxides and rare earth metals,” Rebaudo further writes, “shows that the earths come from the same geological basin, i.e. from the same region,” and that the structural and compositional differences between the clays, which in Statue A have a carbonate matrix with coarse quartz and granitoid fragments, and in Statue B a dark paste of fine clay matrix with a few quartz crystals and small micaceous lamellae, exclude provenance from the same microenvironment, i.e., from the same deposit." Among the areas of provenance, Sicily, Magna Graecia, the Aegean islands, northern Greece, Olympia and Corinth were excluded, Attica seemed unlikely, while Argolis, especially the eastern plain of Argos, and Megarides seem more plausible.

At the moment we can say with certainty that the two Bronzes were produced by two different workshops (we find this from the difference in the castings, which denotes the use of different working techniques), a conviction moreover reinforced by the different origin of the copper used for the details and the different provenance of the clays. As for their authors, further hypotheses have been formulated in addition to that of Professor Moreno mentioned above: rather debated is the hypothesis of Daniele Castrizio, according to whom the sculptures are the work of Pythagoras of Reggio, an important bronze artist active between about 480 and 450 B.C. between the Peloponnese and Magna Graecia, author of theAuriga of Delphi. The idea that only one hand was behind the two works, however, is not compatible with the marked differences in the materials used. To date, however, we cannot formulate sure names, which is why the Riace Bronzes still remain works of unknown artists, although we are sure that they were bronze artists of great experience and skill. And we are also certain that the two works, different in technique, shared the same culture. Therefore, the hypothesis has been strengthened that the two works, although made in two different workshops, belonged in ancient times to the same monument. We know, moreover, that at some time in history the Riace Bronzes were transported to Rome in the imperial age for restoration, during which the right arm and left forearm of Bronze B were replaced by means of a cast of the originals and a new casting. To conceal the operation, a repainting in glossy black became necessary, traces of which can still be seen today.

The Bronze

The Bronze

Detail of the face of

Detail of the face of Detail of the face of Bronze

Detail of the face of Bronze

The Riace Bronzes are a depiction of two hoplites, or two warriors, two soldiers of the heavy infantry of ancient Greece. However, these are not just any hoplites: they are two heroes, because in the art of ancient Greece ordinary mortals were depicted in their clothes and armor, while nudity was reserved for deities or, indeed, heroic figures. The most popular belief at present is that they were part of a single monument. It has been discussed around a report by the writer and geographer Pausanias, who lived in the 2nd century, who reports of a monument dedicated to the feat of the Seven against Thebes, which was located in the agora of Argos, and of which the remains (in particular the structure, the bases of some statues and some inscriptions) have actually been identified. The myth of the Seven against Thebes is recounted in Aeschylus’ tragedy of the same name, first performed in Athens in 467 B.C. E.: It is the story of Eteocles and Polynices, sons of Oedipus, king of Thebes, who agreed to share power over the kingdom inherited from their father, ruling in alternating years. However, Eteocles, at the end of his own year of rule, would not relinquish the throne, and as a result Polynices waged war against him. Polynices, who in the meantime had gone to Argos, therefore besieged the city, garrisoning the gates with his seven strongest warriors-Tideo, Capaneus, Eteocles, Hippomedon, Parthenopeus, Amphiaraus, and himself garrisoning the Seventh Gate. Eteocles had to do likewise, and he deployed Melanippus, Polyphon, Megareus, Hyperbius, Actor, Lasthenes, and himself at the last gate, realizing that it was his fate to clash with his brother. The war began, and the six gates held thanks to the defenders who defeated and killed all of Polynices’ warriors, but the final confrontation between the two brothers ends with the death of both, and with the chorus mourning their fate.

“One might wonder,” wrote archaeologist Sergio Rinaldo Tufi, “why Argos would want to celebrate such an unfortunate feat with a great monument. In fact, the base in the city’s agora housed fourteen statues: not only the Seven, but also the Epigonians, the ’descendants’ who, ten years later, had avenged that disaster by destroying Thebes. The reference to the ancient legend took on the function of projection into myth (something not unusual in Greek culture) of historical events: in this case the long struggle with Sparta. In 494 B.C. the Argives had been beaten by the Spartans at Sepeia, and had lost control of Tiryns and Mycenae, but in 461, allied with Athens, they had won at Oinoe, taking back the two cities. In that same middle phase of the fifth century, the somber grandeur of the ancient affair of the Seven inspired a great tragic poet like Aeschylus: the Riace Bronzes were executed within the span of years in which the tragedy was being completed and then performed, and the fact that a great Argivian author has been identified for one of them has led Paul Moreno to establish a connection precisely with the monument illustrated by Pausanias.” According to Moreno, in fact, the two figures could represent Tydeus, the hero of Argos met by Polynices before the war, who was characterized by a ferocious and bloody violence (in fact, he went so far as to eat the brain of his opponent, Melanippus), and Amphiaraus, the only survivor. According to Castritius, on the other hand, the two statues would depict the two contenders, Eteocles and Polynices: the scholar would link his hypothesis to a report, reported in the imperial age by Tatian, that Pythagoras of Reggio had created a sculptural group depicting precisely the two fratricides (the hypothesis dates back to 2011). Other hypotheses have led to advance identifications with Achilles and Patroclus (Franco Maiullari in 2006), Castor and Pollux (Giuseppe Roma in 2007), and Erythonius and Eumolpus (Vinzenz Brinkmann in 2015).

These are, however, hypotheses for which it is currently impossible to find a match. While we can be almost certain that the Riace Bronzes came from a single monument, it is for now impossible on the basis of the known data to determine what this monument was and where it was located (with a good margin of safety, however, it can be said that the site of the monument was not where the bronzes were produced). However, we can be fairly sure that “the model of reference,” says Rebaudo, "are the great anathemata [votive-celebratory monuments, ed.] such as the Donarius of Lysander or the Donarius of the Arcadians at Delphi, to which artisans from different schools, cities and ages were called upon to collaborate and whose figures could be sent to the sanctuary ready to be installed on the bases, after having been executed elsewhere."

Of the voyage during which the Riace Bronzes sank off the coast of Calabria, we know nothing. The archaeological context of the discovery, in the depths of the Ionian Sea in front of the Riace marina, has not provided much information: among the few materials collected a year after the discovery are about 20 lead rings that were attributed to the ship carrying the two sculptures. Further investigations conducted in 1981 did not yield any major results. The most interesting artifact among those found was an amphora, which was wedged between the right wrist and right hip from Bronze A, which stimulated some speculation about the ship’s hypothetical voyage. The reality, however, Maurizio Paoletti explained, is that “nothing is known about the composition of the cargo, whether of miscellaneous goods or whether it was a selected cargo of works of art (in this case, then, the result of military spoils or trade related to the Roman collecting market). In turn, the total uncertainty about the date of the possible wreck leaves many solutions open.”

Another open question is that of the original number of bronzes, and the alleged discovery of a third statue. On this last point, which for the time being represents nothing more than a supposition fueled by some apparent inconsistencies in the records of the find and by the accounts of some locals, in 2021 the mayor of Riace, Antonio Trifoli, has expressed his intention to promote new research, especially in the area of the finding of the Bronzes, to see if there is a possibility of finding new bronzes. This hope is, in turn, fueled by Castrizio’s hypothesis that the sculptural group of which the Riace Bronzes were part would have included other statues: in particular, next to Polynices would have been his sister Antigone (who tried to mediate to the last between the two brothers to prevent them from coming to a clash), in the center his mother Jocasta, and on the other side Eteocles with the soothsayer Tiresias. The hypothesis follows ancient literature: there is a passage by a first-century Roman writer, Publius Papinius Statius, describing the existence of this group.

In Rome, the Riace Bronzes must probably have been known in the imperial age. But at the moment any hypothesis cannot be further explored: too little evidence is in our possession to come to any definitive or near-certain clarification of the identity of the two statues, as well as to come to any conclusions about the hands that made them. “To hope that our knowledge of the Bronzes can progress solely through the resources of art-historical research,” Rebaudo states lapidarily, “is an illusion. In more than forty years of attempts, stylistic analysis has proven impotent. Progress can only come from an expansion of analytical data, provided that they are subjected to a proper archaeological reading, which has not always been the case so far.” The mystery of the Riace Bronzes, in short, will continue to be such for a long time to come.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.