The resurfaced fleet. History of the extraordinary discovery of the ancient ships of Pisa

Pompey the Great ’s maxim “navigare necesse est, vivere non est necesse,” with which he urged his sailors to put out to sea even though the sea was raging, is still well known. Over time it has been reused countless times as the motto of the Hanseatic League or as a scathing statement of heroism by Gabriele D’Annunzio. More generally, it is often called upon to demonstrate the importance that seafaring, in its dual military-commercial declination, had inancient Rome. That seafaring constituted a load-bearing force in the state, economic, social and organizational system of the time is reconfirmed by the large number of wrecks identified in the deep sea, evidence of how crews were often forced to take to the sea even in unfavorable weather conditions. These dramatic and unfortunate episodes, however, constitute our good fortune, providing us with the opportunity through naval and underwater archaeology to learn a wealth of information about past civilizations.

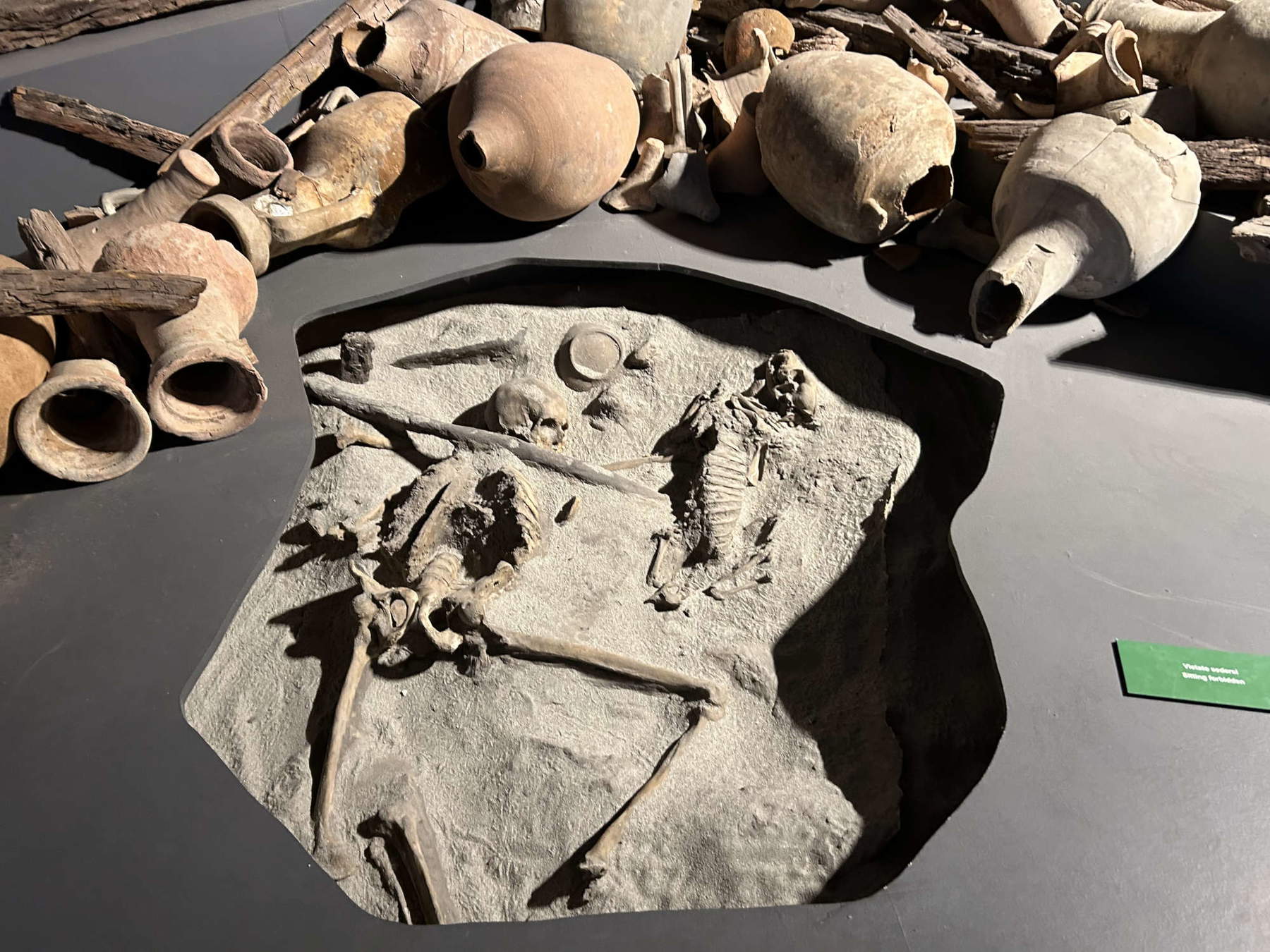

Here it is that among the most extraordinary archaeological discoveries in terms of quantity and quality that have occurred in recent times in our country are the ancient ships of Pisa, the incredible excavation that has unearthed vestiges of more than than thirty vessels, as well as a conspicuous number of finds and artifacts of various kinds, and an incalculable amount of information, so much so that some have hyperbolically (and inappropriately) spoken of a “Pompeii of the sea.”

This discovery occurred by a totally fortuitous chance in 1998, during some work conducted a few hundred meters from Piazza dei Miracoli, aimed at the construction of a service building for Trenitalia, near the Pisa San Rossore station. While the discovery certainly has something unexpected about it, it might appear surreal if we keep in mind that the construction site located in the city center is about 10 kilometers from the coast, but after all, Pisa has had much of its history intertwined with the sea, in antiquity when the coastline was decidedly more set back than it appears today, but also later despite silting up due to deposits of debris of various kinds thanks to the exploitation of rivers and streams.

From the very beginning of the excavation, at a depth of less than six meters, wooden artifacts emerged, which due to specific environmental conditions of the site have maintained a fairly good state of preservation. But no one could have imagined what would soon come to light, and in fact in the first phase the excavation was carried out in the manner of emergency archaeology, that is, with the goal of focusing on the identification and recovery of artifacts in the area, and the work at that time was financed by the Railways itself. But already a few months later it was realized that what was preserved underground was beyond all possible expectations. The large and exceptional quantity and quality of the finds highlights the importance of the discovery, for which as early as the summer of 1999 it was decided to proceed with a construction site of an intensive nature, creating an area designated for systematic research and with a design of a much longer duration than initially budgeted. These first finds were carried out under the direction of archaeologist and professor Stefano Bruni first and then Andrea Camilli.

This laborious stratigraphic excavation, which covered an area of more than 3500 square meters, soon prompted the Railways to abandon the planned infrastructure project, which was rethought for Pisa Central Station.

Not a few problems appeared before the archaeologists involved in the investigation, chief among them the specific environmental difficulties of the area, formed by sedimentary layers of considerable thickness and the pre-existence of a copious water table.

To obviate the water problem, the continuous use of mechanical pumps was resorted to, while the other major difficulty , that of coping with the rapid degradation and dehydration times of the unearthed wooden materials, combining them with the laborious requirements of a stratigraphic excavation, were obviated by opting for an excavation in “sections,” that is, uncovering only small portions of the wrecks, which, once documented, were again covered with a thin layer of fiberglass, while ensuring a continuous and proper degree of humidity through a timed irrigation system.

At the same time, it was decided to set up a restoration center to respond to the need to prepare different techniques of intervention on the unearthed artifacts, especially for wooden artifacts, to which, once washed and desalinized, the volume of water must be replaced by impregnating them with other inert substances, possibly removable. Thus took origin the arrangement of the wet wood restoration laboratory.

This impressive deployment of forces and economies depended on the exceptional nature of the find, a conspicuous number of overlapping wrecks lying on silty, sandy shoals. These are remnants of vessels dating from different eras, which were dragged into this deposit by the repetition over the years of a series of powerful floods, probably related to the deforestation of the soil operated for the organization of navigable mirrors and waterways and to allocate land for agriculture.

Andrea Camilli himself spoke of a number between nine and twelve floods that involved the whole territory and that “overwhelmed the ships and made them sink, all in this intersection between a river and a canal, crowding them together like in an immense game of shanghai. Here, the excavation has been this. It was a game of shanghai in which by finding one ship you would then find another one underneath.”

The material found, which can be dated from the Hellenistic to the Late Antique period, consisted not only of the remains of the hulls and planking, but also of a large amount of fictile material such as Greco-Italic amphorae, for which only some of the accepted the possibility of being components of the maritime cargo related to the vessels present, since for some characters of typological and chronological inhomogeneity the hypothesis has been put forward that they were waste material disposed of over time.

Numerous reconstruction proposals have been made on the origins of this flourishing deposit, which indicate that in Roman times the settlement of Pisa was originally built in the area of the alluvial plain of the Arno, where other watercourses, including the Auser (now Serchio), also met. Confirming the flood hypothesis would be the findings made on at least five sets of deposits referable to traumatic natural events that caused ships to sink.

Although accumulations of stones were found, to be understood according to Camilli himself as “forming part of an arrangement of the river banks, consisting, rather than a series of piers, of a rough embankment with internal buttressing”, while the rectilinear walled structure perhaps belonged to the landing place of a manor house, the area of the excavation would thus be recognized instead of a harbor, as a waterway, an extensive roadstead affected in Roman times by intense traffic. The investigation conducted on the wrecks has led to an incredible array of numerous pieces of information that have made it possible at least in part to reconstruct their use and history.

Among the remnants of older vessels found, one known as a Hellenistic ship has been recognized for which a date has been hypothesized on the basis of the furnishings found on board, pertaining to the 2nd century BC. The ship must have habitually moved on a developed trade route between Campania and Spain, and carried various kinds of merchandise, including pork shoulders preserved in brine.

Ship A, on the other hand, was an oneraria, that is, a large vessel devoted to trade: in fact, it must have exceeded forty meters in length, although only half of it has been preserved, and has been dated to the end of the second century A.D. It carried amphorae of various origins containing canned fruit.

Among the most prestigious pieces is a twelve-oared ship, of which the tablet with the name Alkedo (the Seagull) was also found, which is among the best-preserved vessels. Ship I, on the other hand, is a flat-bottomed river ferry to be dated to the fifth century CE; it was propelled along the banks by a system of ropes and a winch. Also for river use was boat D, a large barge that carried sand along the waterways, and moved either propelled by the wind thanks to a sail, the mast of which is preserved, or towed from the shore through animal power.

Other finds from boat F and boat Q are to be recognized in the typology of lintres, boats not unlike dugouts, which were propelled by oars, and could be used for small transports of goods or people.

During the excavation the remains of another thirty boats were counted, but the same number was later questioned by other scholars. But the exceptional nature of the recovery did not linger only on the ships and their precious cargoes; in fact, the bones of a dog and a sailor, who is thought to have sacrificed himself in an attempt to save his animal friend, were also found in the deposits. There are still numerous artifacts from the past, such as glassy ones used as glasses and balsamware destined for a luxury market, wood and stone remains, coins, sailors’ luggage, and as already extensively highlighted the fragments of more than 13,000 amphorae.

This momentous find has made it possible and will still make it possible in the future to increase our knowledge on a variety of topics, ranging from river and maritime systems of ancient navigation, to information on trade, contacts between peoples, the role played by Pisa over the centuries, plus the excavation has established itself as a nearly 20-year training ground for the experts in the field and the students involved.

Most of the finds are now included in an evocative museum itinerary in the Museum of Ancient Ships of Pisa, which from 2019 will find space in what were the Arsenali Medicei, thus going on to recompose a temporal parabola that from antiquity to themodern era saw the Tuscan city boast a close connection with the sea and navigation, bringing back into the open a more complex and richer narrative of the area that cannot and should not be limited solely to that of a medieval center dominated by the iconic Leaning Tower.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.