Theswing has always been among the freest and happiest games a child knows: it is a safe, public and impersonal nonplace where one pretends to fly while the air dishevels one’s hair with irreverence and escape, dreams, seem to be a few inches closer to being realized. But if that same swing decides to inhabit the uninhabitable, to swing into an eerie underground structure, all of a sudden freedom would turn into imprisonment. And this is precisely the work carried out by artist Mona Hatoum who, for this year’s edition of the Bruges Triennial, Space of possibility, decides to stage her Full Swing by making a distressing visual oxymoron.

Beyond the Bruges station and past the city bustle typical of downtown lies, in the garden of the Onzelievevrouw psychiatric hospital, a very low wall made of stones of different sizes held tightly together by a wire mesh. Approaching that low wall one discovers a kind of dark dungeon that at its center holds a swing that remains suspended. The only escape seems to be the sky, an unreachable blue window, mocking in its futile promise of freedom. And that sky becomes a forbidden dream that relegates the visitor to an iron purgatory and among the prisons of his head. Along with the seesaw one swings between light and dark, between trap and indomitable escape, between joy and discomfort, but as one continues to sway one realizes that what reigns is only a sense of insecurity and restriction. The walls seem to tighten with each breath, the sky seems more and more distant, and the creaking of the strings engulfs thought. Each step violates the silence and resonates like a deaf echo, a stifled wail that creeps into the folds of the mind, but at the same time offers the possibility of physically experiencing, in a tangible way, the feeling of living in conditions of confinement.

All surfaces of the work are made of local stones and take inspiration from the containment gabions typical of military and prison environments. Nothing is left to chance: even the place where the swing is placed turns out to be of paramount importance, and the garden of Onzelievevrouw Psychiatric Hospital, which takes shape in the distance, puts people in a forced relationship with the history of the surrounding place.

During the Middle Ages, individuals with mental disabilities were housed in a special "dulhuus " (asylum): an urban institution similar to other hospitals in the city, in which care was initially provided only by lay people. Texts concerning psychiatric hospitals in Bruges are rather scanty, but a regulation drafted in 1596 for the Sint-Hubrechts asylum tells how the facility was given over to a kind of warden whose job was to care for the patients, to check the locks and chains “so that the aforementioned would not break,” to clean the cells and supply them with the necessary straw, and, last but not least, to feed them three times a day with bread, butter, and thick soup while the city paid for their clothes and wood to heat the house.

It was in 1793, however, that the first asylums were officially born in Europe through the intuition of French physician Philippe Pinel who, according to legend, freed the mentally ill from prisons since they could not be equated with criminals. Asylums were well received during the first half of the 19th century in France, Germany and the United States: however, inside them the sick, divided by disorders, were subjected to constant harassment, torture, frozen baths, straitjackets, bloodletting and much more. At that same time the “Dutch Pinel,” a certain Joseph Guislain, promptly decided to apply these treatments at the Buitengasthuis in Amsterdam and the Dulhuys in Utrecht. It was psychiatrist Wilhelm Griesinger, however, who overturned the French model by proposing peripheral institutions with very few beds and inpatient stays of no more than a year, and on this model the Gheel psychiatric clinic in Belgium was born, where mental disorders were treated with work in the fields. There are many centuries of darkness in the history of asylums, and it is over this history that the work Full Swing arises.

We know that by the beginning of the 20th century, the Onzelievevrouw facility had become so obsolete that an immediate renovation was needed. On December 8, 1906, architect Jules Coomans began designing and supervising work on the hospital as we know it today. It was then opened on August 17, 1910, and from here on medical care was innovated through an organization into departments for different types of insanity, without separate pavilions. Again, during World War I, things changed again, and the evacuation of nurses and patients caused a period of stagnation that lasted until the end of World War II, after which the hospital became briskly operational again. With medical and therapeutic advances in the second half of the 20th century, the hospital underwent significant renovations and, in the 1980s, an ambitious master plan was launched to build a nursing home with new nursing wards, single rooms, and private toilets, located in what is now a very quiet park. There could not, therefore, have been a better space to house the work of Mona Hatoum, who, from her earliest works, has been investigating a sense of oppressive imprisonment and control, embodied by the typical architecture of detention facilities. Full swing brings together all those materials such as metal grids, swings and cages that recur obsessively in her works telling stories of suffocating violence.

The experience of escape returns incessantly in her art and becomes the lens through which Mona Hatoum views the world and relates to it. Born in 1952 in Beirut to a Palestinian family, she was forced to settle in London in 1975 due to the outbreak of civil war in Lebanon. Her artistic research starts by weaving a constant dialogue between the past in a denied land and the experience of a migrant woman. Although she has been working in England and Europe for years, the memory of why she could not return to her places of origin, rather than the places themselves, continually resurfaces in her works. The artist initially uses her body to denounce her experience as a woman and migrant, seeking extremely political language to discuss the foundations of her condition. The theme of identity is an inescapable starting point that is then deepened through a tension of materials that give no respite and whose relationship never resolves itself into abandonment, but continue to struggle convulsively and tenaciously, creating an unsettling creak between flight and return, between belonging and abandonment.

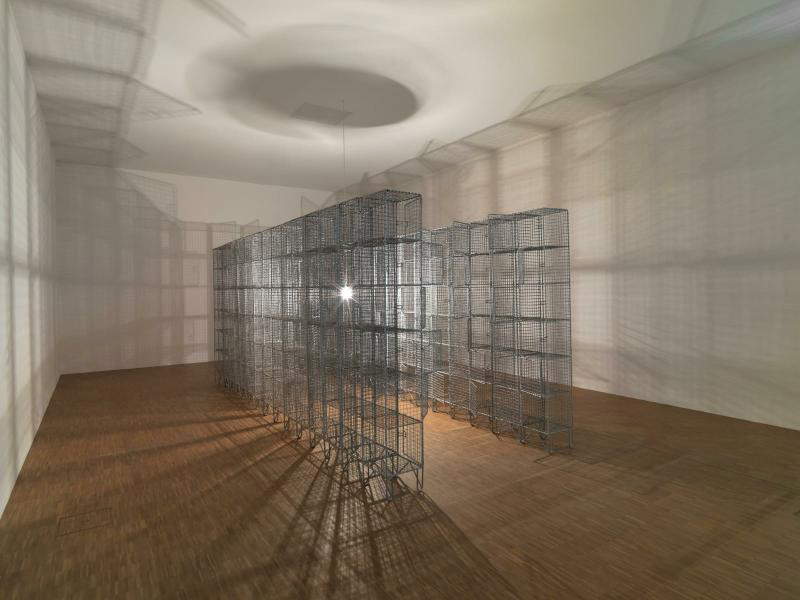

But it is since the 1990s that, for Mona Hatoum, the exploration of her own body gives way to the physicality of the rooms that begin to become hominous containers of the mind: the house becomes a cramped space, in which its theoretically “nest” being has to reckon with the constant contradiction with rejection and the impossibility of reception. And so, every object present becomes a trap: beds in which it is not possible to sleep, a seat-grater that denies the possibility of sitting and resting, the household appliances that are nothing more than cruel scientific experiments, and the swings that hinder dreams. With each of her works, the artist weaves a tapestry of evocative and never didactic images that reveal harsh realities of oppression, violence and exile that immerse the viewer in a liminal world where light and shadow intertwine and create macabre dances with contradictory meanings. Bars and the feeling of being eternal prisoners in a way that fails to love you take on a haunting centrality, as in the 1992 work Light Sentence , in which metal cages, illuminated by an aseptic white light, are transformed into long shadows that engulf the surrounding space. The continuous juxtaposition of light and shadow only evokes that constriction typical of imprisonment, physical and psychological, which, even if one has never experienced it, inside the fake cages becomes something real, like a distant reminiscence. In 2011, with Suspended, he placed thirty-five red and black swings in a room, each affixed with a street map of a different capital city. These swings, in constant motion and hung at an oblique angle to the one nearby, create a sense of dislocation and instability, alluding precisely to the flow of migrants around the world and showing the imbalance created by war and the randomness of its victims.

As is also the case with the work Full Swing, which can be visited in Bruges until September 1, 2024, Hatoum uses materials that, taken individually, seem almost banal and bends them under her will, creating worlds dominated by artificial boundaries that convey an unbearable heaviness of soul.

This installation demands to be experienced individually, and only in this world can one fully perceive the claustrophobic anguish it wants to convey. It requires one to descend into a narrow corridor, unarmed, and as one travels down it to get to that lonely swing, the screeching of the stones becomes one with the chills that spread inside one’s bones. Once on the eerie merry-go-round its metallic creaking, haunting as a ghostly wail, punctuates the suffocating silence of the narrow cell. Each swing is just an echo of loneliness, a scream tearing through the still air and amplifying each individual’s desolation. With each swing, the feeling of imprisonment in the darkness of the earth gives way to the yearning for ascent, for liberation, and the body, imprisoned in space, seems to turn into a gravity-defying pendulum yearning for an impossible freedom from that hole in the ground.

“Since I arrived in London,” says the artist as she looks down on her prison from above, “I began to understand and feel a brutal control. I realized that we are constantly being watched like in Orwell’s Big Brother and this is what pushed me to look at power structures, especially prisons that make you feel so small and insignificant.”

Full Swing deals precisely with the theme of imprisonment, the restriction of movement, and above all exhibits the momentary inhabitant of the hellish corridor to the curious eyes of the people above, who lean against that little gray wall that falsely swears to protect them from all that is evil, different, and unknown, which in that moment is you.

Art is stripped of all futile utopia and does not believe in salvation because, in the end, the prisons of the mind are the most devious and vicious.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.