The Polyptych of St. Augustine, Perugino's most complicated work

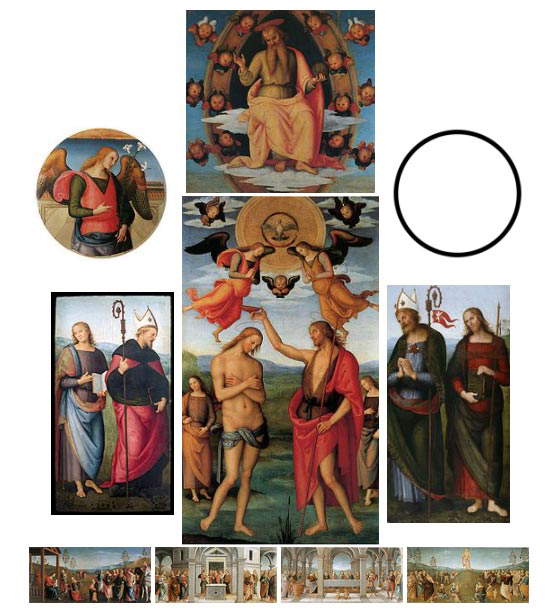

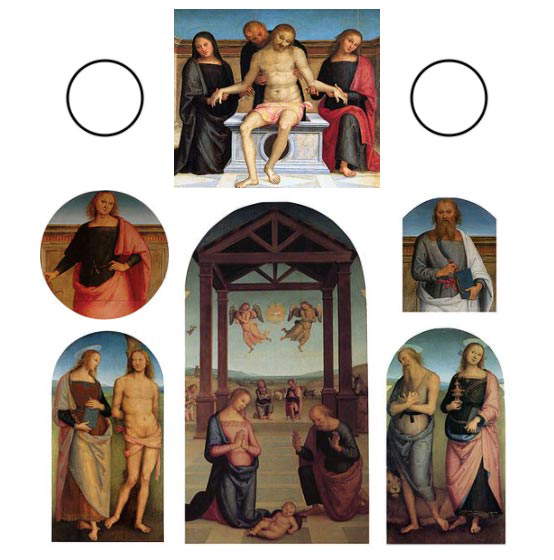

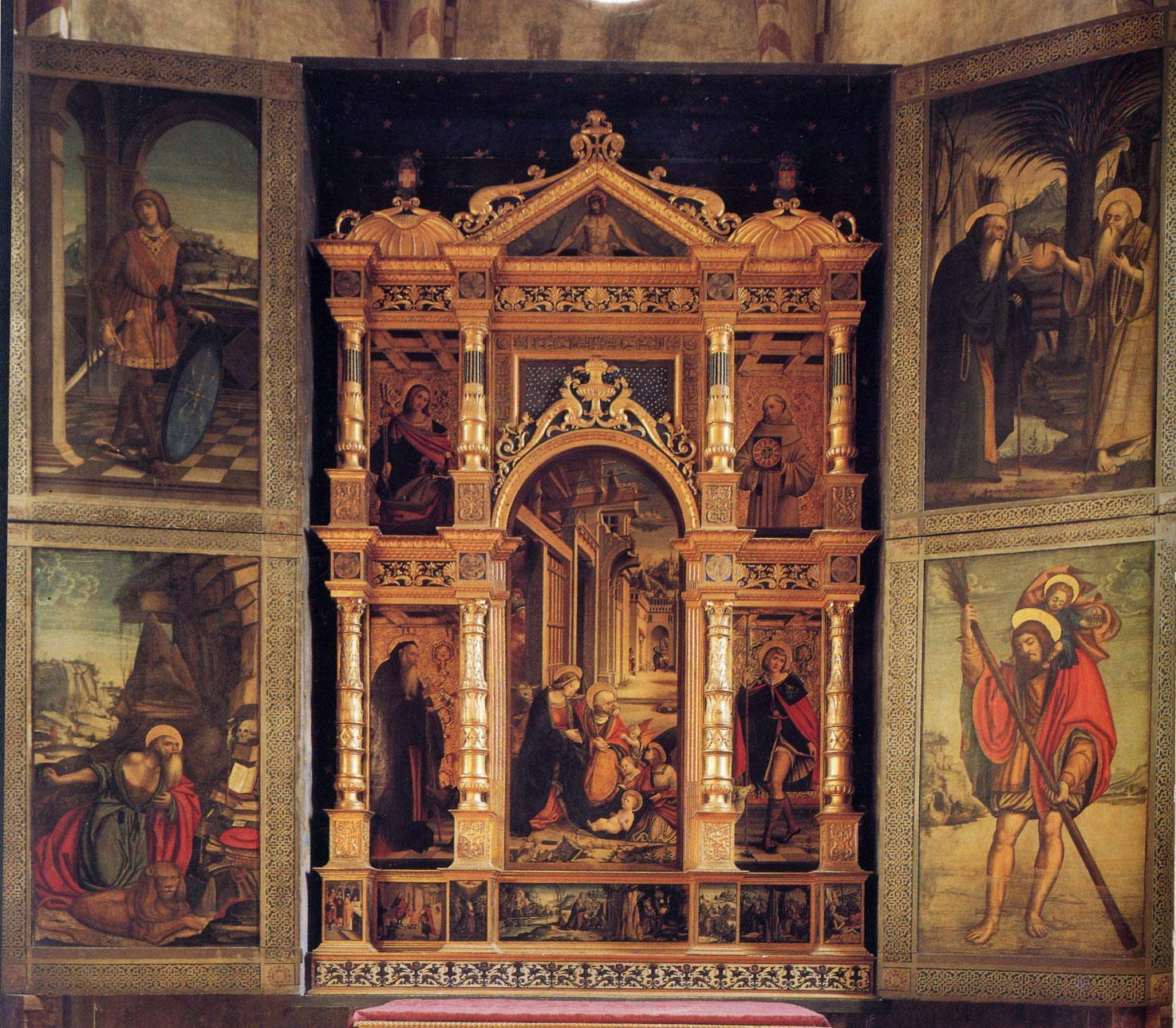

If you visit the Late Perugino room at the National Gallery of Umbria, where works from the extreme phase of the career of Pietro Vannucci known as Perugino (Città della Pieve, 1450 - Fontignano, 1523) are kept, you will notice two panels displayed side by side, one in rectangular format depicting the Baptism of Christ and the other, centered, presenting an Adoration of the Shepherds. These are the only two exhibited parts of what was once the Polyptych of St. Augustine, and looking at these two panels alone it is impossible to realize the complexity that this altar machine must have had when it was whole: to get an idea, you can go to the next room and look at Pinturicchio’s Altarpiece of Santa Maria dei Fossi , since according to the most recent reconstructions Perugino’s polyptych must have had an extremely similar structure to that of his colleague.

It was a complicated work with a long gestation, commissioned from the artist in 1502 by the Augustinian friars of Perugia, who intended to destine the work for the church of Sant’Agostino, and went on until the artist’s death in 1523: when the artist died in Fontignano, in fact, the figures of the prophets were still missing. From the documents that have come down to us we can reconstruct the work, which had to fit the large wooden carpentry (now completely lost) that the Augustinians had commissioned on April 23 from the carver Mattia di Tommaso da Reggio, that is, the same author of the carpentry of the altarpiece of Santa Maria dei Fossi, who completed his work around 1500, the time when the friars were able to obtain the possibility of installing it on the high altar. A painter was needed, therefore, to complete the frame with the paintings, and the latter was identified in Perugino, who was paid the considerable sum of 500 gold ducats (to give an idea, it will suffice think that the frescoes in the Sala delle Udienze in the Collegio del Cambio earned the artist 350 ducats, while the Lotta tra Amore e Castità, commissioned by the marquise of Mantua, Isabella d’Este, and finished in 1503, had been paid 100 ducats). It was indeed a considerable challenge for Perugino, not least because of its size, so much so that the woodwork, once completed, had to be disassembled to allow it to be transported to the painter’s workshop: the whole was then reassembled when Perugino delivered the most important elements. The artist received the agreed sum partly in cash, and partly through the transfer of real estate. By the date of 1512, however, the work was not yet finished (the artist at the time was engaged in numerous other commissions), so that a new writing between the painter and the friars became necessary, from which we know that at that time the artist had received about half of his fee. Perugino, in this document, undertook to complete the work by April 1513. Later the artist would get a further extension until Christmas 1521, but as mentioned he died before finishing the work, and what was missing had to be done by the workshop. It was not until 1525, two years after Perugino’s death, that the huge polyptych was placed on the high altar of Sant’Agostino.

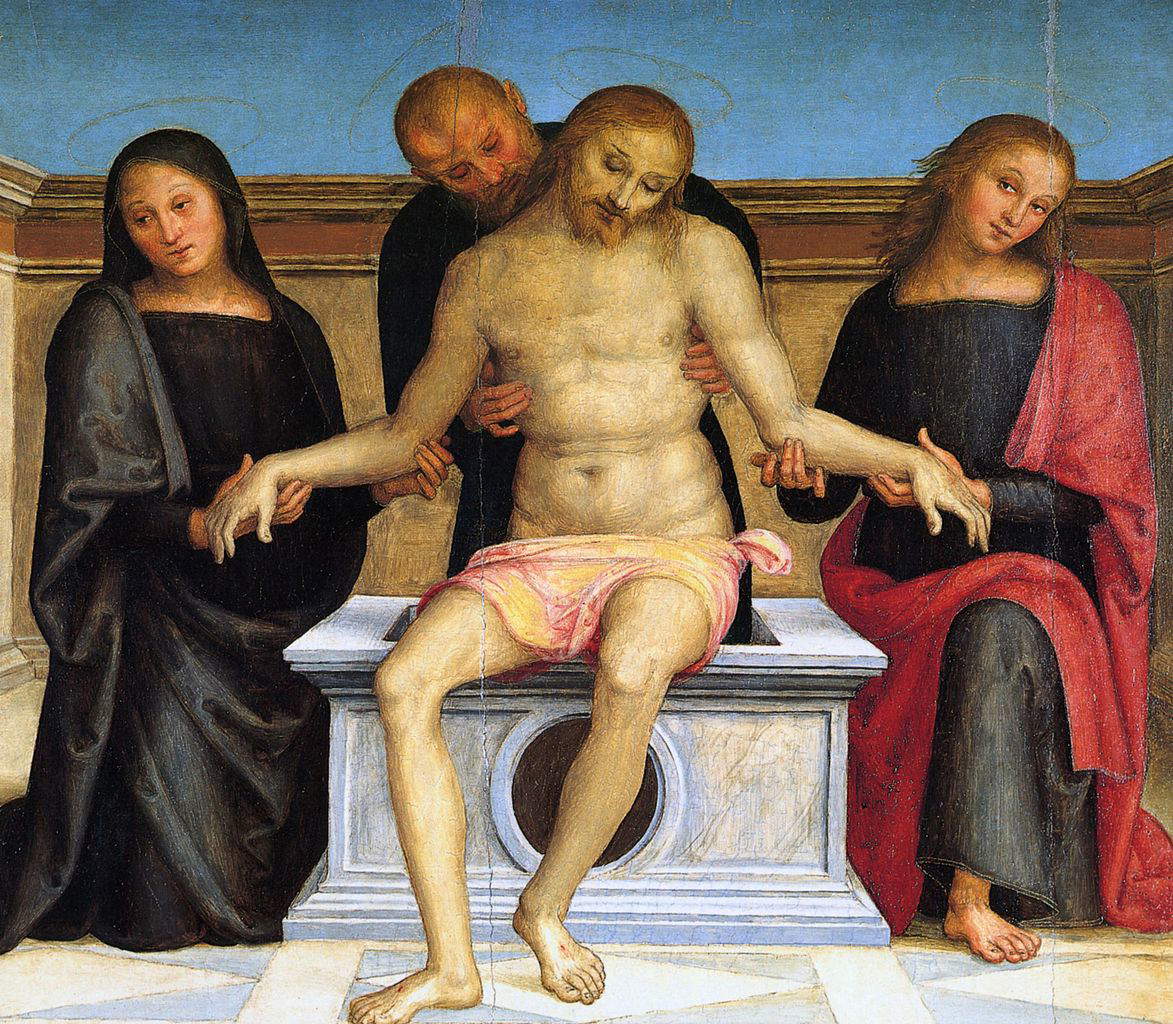

In any case, even after Perugino’s demise the Polyptych of St. Augustine did not have an easy life. In 1580, in fact, the work was altered: in front of the panel with the Baptism of Christ, which was in the center of the main register, facing the faithful (the work was in fact opisthograph, that is, painted on both sides), a gilded tabernacle was added and painted by Onorio da Giuliano, and in 1654 the polyptych was dismantled, basically because it was no longer in line with the liturgical practices of the time. Shortly thereafter, in 1683, the panels were removed from their original frames, and at an unspecified time, probably in the 18th century, some of the panels were lost: in particular, today we do not know the fate of the two prophets in the cymatium and the Virgin Announced (we do, however, know her appearance from an engraved reproduction and a copy). All the panels were dispersed in the Napoleonic era and today are kept at various museums. The National Gallery of Umbria, although it displays only the two central panels, is the museum with the largest number of surviving panels: the Padreterno Benedicente, the prophet Daniel and the David of the cymatium, the archangel Gabriel and Saint Jerome with Saint Mary Magdalene of the central register, and all the panels of the predella are in the Perugia institution. In contrast, the Pietà of the cymatium is in the Museum of St. Peter in Perugia, the compartment with St. Philip and St. Augustine of the central register is in the Musée des Augustins in Toulouse, and the one with St. James the Greater is in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Lyon. Also found in France are the compartments with St. Martin of Tours (in the Louvre) and with St. Irene and St. Sebastian (in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Grenoble), and finally the panel with St. Bartholomew is in the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama.

According to the reconstructions proposed by Vittoria Garibaldi and Christa Gardner von Teuffel on the occasion of the major exhibition on Perugino held in 2004, and arrived at following several attempts made by the scholars who have dealt with it (Walter Bombe, Ettore Camesasca Jean Habert, Fabio Marcelli, Piero Nottiani, Luigi Petrini), the two central panels were flanked on both sides by as many panels depicting saints, above which were the roundels (which, however, were originally square: those with the Archangel Gabriel and the Virgin Announced on the side facing the faithful, and two prophets on the side facing the friars: the only two that remain to us, David and Daniel, were probably made by Perugino’s workshop after his death), while the panels in the center were surmounted by the cymatium panels (the Padreterno facing the nave and the Pietà facing the apse), which were in turn flanked by two tondi each. The front probably appeared different: during the restoration conducted in 2004, it was found that the clypeus that stands out in the upper part of the Baptism of Christ, the one where the dove of the Holy Spirit is depicted, has an abraded surface, a sign that it underwent color removals (traces of which were also found), and that therefore another figure was originally painted here, in this case a blessing Eternal, as the traces found suggested. Why, then, paint an Eternal Father ... double? In all likelihood, Perugino imagined that the delivery of the panels would go on for a long time, and imagining that the cymatium would be among the last elements to be delivered, in order not to leave the painting iconographically uncluttered (thus foreseeing a display to the faithful before the end of the work), the artist, in agreement with the commission, painted a Padreterno inside the Baptism of Christ and then removed it later. This, at least, is the hypothesis of Luciana Bordoni, Giovanna Martellotti, Michele Minno, Roberto Saccuman and Claudio Seccaroni, authors of an essay on the polyptych, who have, moreover, proposed a different reconstruction. This expedient would therefore suggest a certain understanding between the artist and the patron, making it likely, as the authors write, that there was “an agreement for a delivery in progressive stages, perhaps also linked to the work on the choir that made the presbytery unfit for use.”, reasoning that “the second contract [...] would not have been dictated so much by a desire to nail the painter to commitments to which he was proving to be in default, as it would have sanctioned the resumption of work on the rear front, with a view to the forthcoming arrangement of the stalls in the choir.”

Perugino

Perugino Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino

Perugino Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino,

Perugino, Perugino

PeruginoReconstructions have always taken into account the drawing by the Augustinian friar Giacomo Giappesi, who in a manuscript of 1710 reproduced the outline of the front facing the apse, and is a valuable document for getting an idea of how the Polyptych of St. Augustine must have looked in ancient times. Perugino first completed, between 1502 and 1513, the panels facing the front, while in the later period he worked on the panels facing the back of the church. Curiously, all the paintings facing the nave were quadrangular in shape, while those at the back of the polyptych were centered in shape.

The machine, Vittoria Garibaldi wrote, was “more than eight meters high, composed of at least thirty painted panels, enriched by columns, pilasters, friezes, cornices and architraves, a true architectural structure of division between the chancel and the presbytery [...]. The chest that reached up to the lintel above the main register, as with the Benedictine altarpiece, was both an indispensable structural element of connection between the wooden machine and the walls of the presbytery and a clear separation between two different liturgical places.”

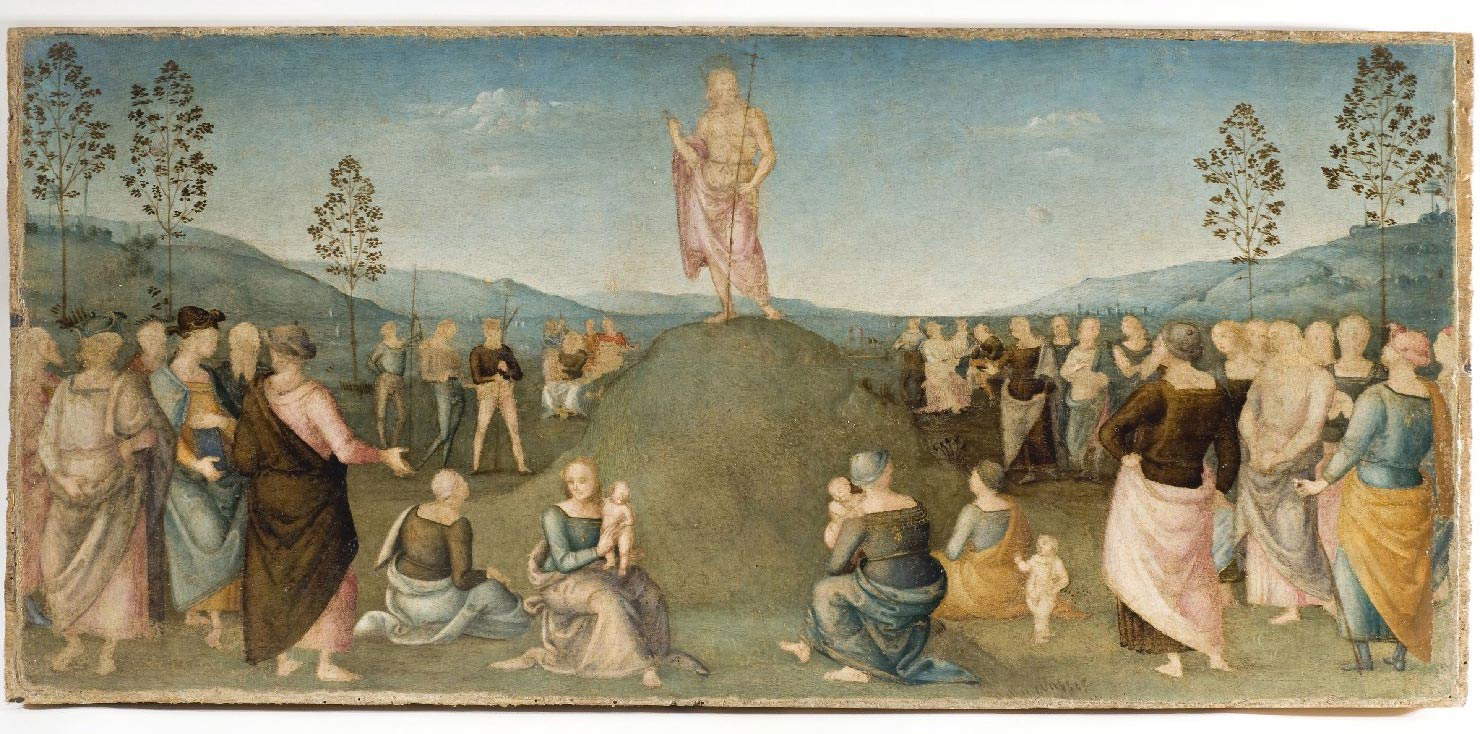

The Augustinian friars had chosen a rather complex iconographic program for their polyptych, combining, as Christa Gardner von Teuffel explained, "themes of the Incarnation and acceptance in the church through the Holy Trinity made familiar precisely by the teachings of St. Augustine, the mentor of the order, and of Egidius of Viterbo, its principal contemporary exegete.“ A program, completed by the predella panels also related to the Eucharistic interpretation of the large panels, that ”directly connects the reconstituted altarpiece to St. Augustine and confirms its original purpose." It cannot be said that the Polyptych of St. Augustine is among the most original achievements of Perugino, who indeed lavished a less than strenuous effort in the execution of the project, and resolved the painted scenes with a certain conventionality. It is then also a discontinuous work, since its realization took twenty years, the last twenty years of Perugino’s career: in the front section we therefore find an artist who is still in the prime of his work, an artist who received the commission when he was at the height of his success, and who consequently, while taking up formulas that had already been widely tried and tested (the Baptism of Christ that Perugino paints in the central panel recalls the one executed twentyyears earlier in the Sistine Chapel), he succeeds in offering a markedly different proof from that of the back of the polyptych, in the panels painted when the artist was by then heading into his twilight years, where, however, a different technique is noticeable, decidedly more fluid and synthetic, almost impressionistic, to use an anachronism.

The panel with the Baptism of Christ is therefore, for sure, the best of the polyptych: painted in the early stages of the work, it demonstrates all the qualities of Perugino’s style of the time, namely a very fine drawing, full modeling, bright colors, delicacy even in the details. The same cannot be said of theAdoration of the Shepherds , which is instead found in the part that in ancient times faced the friars: one notices even with the naked eye how the drawing appears less still and more fragmented, or how the landscape appears less rich than that of the Baptism, and how the brushstrokes are more fluid and quicker. Differences are also noticeable in the conduct of the chiaroscuro hatching, which is very dense in theAdoration of the Shepherds, and less precise in the panel with St. Jerome and Magdalene and in the paintings of the cymatium.

It is, however, a unicum in Perugino’s entire production, and its uniqueness is due both to its monumental size, its structure (apart from the frescoes, it was the most challenging work among those painted by the artist from Città della Pieve), and its exceptionally long time frame. To give an idea of the complexity of the machine, it will be appropriate to recall that in 1512 the Augustinian friars commissioned Giovan Battista di Cecco di Matteo, known as “Bastone,” to paint a “capssa,” or chest, which was to be decorated by Eusebio da San Giorgio, and about whose nature it was debated, between those who believed it to be a wooden structure that was meant to connect the polyptych to the walls of the chancel or those, like Von Teuffel, who understood it to be a huge closet with opening doors, like the one that encloses the Ranverso Polyptych, a masterpiece by Defendente Ferrari, preserved in the Abbey of Sant’Antonio di Ranverso in Buttigliera Alta, Piedmont. Even in the final years of his career, in short, Perugino never stopped embarking on feats that few other artists were able to tackle.

The article is written as part of “Pills of Perugino,” a project that is part of the initiatives for the dissemination and diffusion of knowledge of the figure and work of Perugino selected by the Promoting Committee of the celebrations for the fifth centenary of the death of the painter Pietro Vannucci known as “il Perugino,” established in 2022 by the Ministry of Culture. The project, edited by the editorial staff of Finestre Sull’Arte, is co-financed with funds made available to the Committee by the Ministry.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.