|

| SandroBotticelli, Primavera (c. 1482; tempera on panel, 207 x 319 cm; Florence, Uffizi Gallery) |

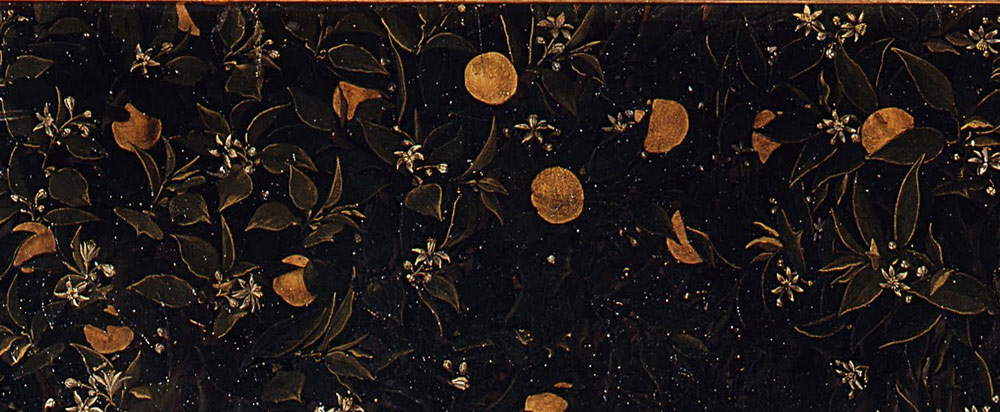

Anyone who has leafed through an art history textbook and lingered on the pages devoted to the great Florentine artist will surely have found a quick reference to the huge number of plant species depicted in Primavera: there is no book that, when speaking of the great painting preserved in the Uffizi, does not mention that Botticelli depicted there hundreds of specimens among flowers, shrubs, grasses, trees and vegetables in general. Such a conspicuous presence of plants responds to several needs: the first is obviously to circumscribe the time of year that is the subject of the work, because the species represented by Botticelli, as one can imagine, all bloom, grow and sprout in spring. The second is to suggest symbolic cross-references: this explains, for example, the presence of the orange trees that yes present their zagaras, the white flowers typical of citrus fruits, but are also laden with fruit, when it is well known that the orange tree bears its fruit towards the end of autumn. In fact, the orange is a Medici emblem: easy to understand why if you know the Latin name citrus medica, which today scientifically designates the citron but in ancient times, at least according to the nineteenth-century botanist Giorgio Gallesio, was also used to indicate the orange. Moreover, the citrus fruit is also a symbol of marriage, because according to ancient mythology the goddess Juno is said to have given her husband Jupiter orange plants as a wedding dowry. If, moreover, one takes at face value the albeit debated dating that would have the Primavera painted in 1482, the creation of the work would fall in the year of the marriage between Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici and Semiramide Appiani.

|

| Detail of the orange trees with fruit and orange blossoms |

It is then necessary to point out what a great connoisseur like Herbert Percy Horne noted, namely, that the species depicted by Botticelli are almost all typical of Tuscany: and in this willingness to make use exclusively of local species, Botticelli differed, for example, from a Poliziano who also referred in his lyrics to plants described in classical sources but unavailable in and around Florence. Nothing prohibits us from thinking that Botticelli found the flowers in the very gardens of the Villa Medicea di Castello, the residence for which Primavera was intended. There is no shortage of flowers and shrubs that are products of the artist’s imagination, but these are still not very frequent cases.

Perhaps the most decisive contribution to a precise identification of the plant species in Botticelli’s Primavera was offered in 1984 by botanist Guido Moggi, longtime director of theBotanical Garden of Florence and the Botanical Museum of the Florentine university: the restoration of Botticelli’s masterpiece was then ending, and the occasion had become propitious for an in-depth study of the botanical species that the great painter had depicted in his painting. “The important botanical component,” Moggi emphasized in his contribution, “constitutes one of the most striking and characterizing elements of the work. Indeed, numerous botanical species are represented there, some corresponding to real plants, others to more or less imaginary or stylized elements.” We find the greatest number of species, of course, in the lush meadow on which the protagonists of the scene move. The fact that Botticelli almost totally excluded fruiting plants from his composition is an exceedingly significant detail for understanding his intentions: to celebrate the time of year when plants bloom. In particular, we are in the months of March and April, and, as mentioned in the opening, Botticelli was quite precise in showing only plants that bloom at said time of the year (although the presence of some blooms typical of the month of May is recorded), and he was also very rigorous in the tout court representation of the plant elements in the painting, although there are instances in which Botticelli depicted, for example, a flower belonging to one species and leaves belonging to a different genus.

Therefore, let us take a closer look, following the contributions of Guido Moggi and Mirella Levi d’Ancona (we quote them in the bibliography), at which botanicals Botticelli depicted in his Primavera and what their possible meanings were. We can start with an observation by Guido Moggi, namely, that about five hundred specimens would appear in the painting, of which about seventy would be simple tufts of grass belonging to the grass and cyperaceae families. The remainder are divided into non-flowering plants (about two hundred and forty specimens: Moggi was able to identify thirty-one and attribute them to fourteen different species) and flowering plants. Of the latter, one hundred and thirty-eight specimens attributable to twenty-eight species were identified with certainty: the total number of recognized genera of plants thus rose to forty-two (excluding flowers painted on the robes of characters, and trees in the woods). The two most numerous species are daisies, which appear fifty-five times, and violets (forty-six): two flowers that grow wild in meadows in spring and are as emblematic as ever of the beautiful season. They are, however, also symbols of love: the daisy also as a flower used in the typical game that is supposed to let the lover know if his love is reciprocated, and the violet, as a flower sacred to Venus, because at her birth the goddess would have been crowned, precisely, with violets.

We find a great variety of different species at the feet of Venus herself, appearing before a large bush of myrtle, a plant sacred to her. There are, of course, roses in profusion: these are mostly the ones that Flora, the personification of Spring, carries in her lap and is scattering on the lawn, where we already find some of them spilled. The rose, also a spring symbol, was another flower sacred to Venus, associated with love and beauty, and moreover later passed on to Christianity as a Marian symbol of purity. Under the feet of Venus we find a hellebore flower: the flowers of this plant were believed to prolong youth (and youth is an attribute of Venus), but also to cure insanity, and it is well known howlove can induce such an altered state (the insanity that follows unrequited love is a typical topos of certain ancient literature). Immediately next to the hellebore we find some flowers of blue viperine, so called probably because in ancient times it was believed to be a remedy for the bite of the snake from which it takes its name: it is a plant that blooms in early May, and supporters of dating the painting to 1482 have seen in this viperine a further reference to the marriage of Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de’ Medici, who was married in the month of May. The same is true of the camomile, also next to the hellebore. The presence, next to the viperine, of ranunculus, which is symbolic of death (because of its toxicity) has led some to assume that Botticelli began painting Primavera for Giuliano de’ Medici, brother of the Magnifico, who fell during the Pazzi conspiracy. Further below we have instead some toxylaggine flowers (the name still refers to the healing properties, in this case against coughs, but the plant is also known as farfara), while if we proceed to Flora’s feet we will notice, among the roses thrown by her on the lawn, first a strawberry seedling, then a muscari plant (a coninugal symbol) and then, further above, a pink hyacinth and a poppy. The strawberry, as a tasty fruit, is a symbol of the pleasures experienced during the warm season, the hyacinth is a wedding flower while the poppy was anciently believed to be a sign of fertility. Between the left foot of Venus and the mantle of Flora, on the other hand, we have a cornflower seedling, another symbol of love, particularly related to marriage. Proceeding instead in the opposite direction, toward the feet of the three graces, we find some jasmine flowers, another flower that opens in the month of May.

|

| The goddess Venus with, behind her, the myrtle bush |

|

| Plants and flowers on the meadow. 1: Daisy; 2: Violet; 3: Rose; 4: Ellebore; 5: Blue Viperine; 6: Toxilaginum; 7: Strawberry; 8: Muscari; 9: Poppy; 10: Cornflower; 11: Jasmine; 12: Pink Hyacinth; 13: Ranunculus |

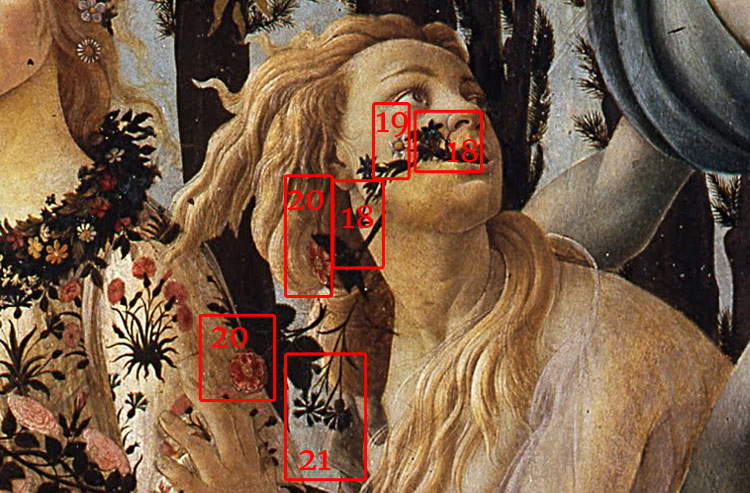

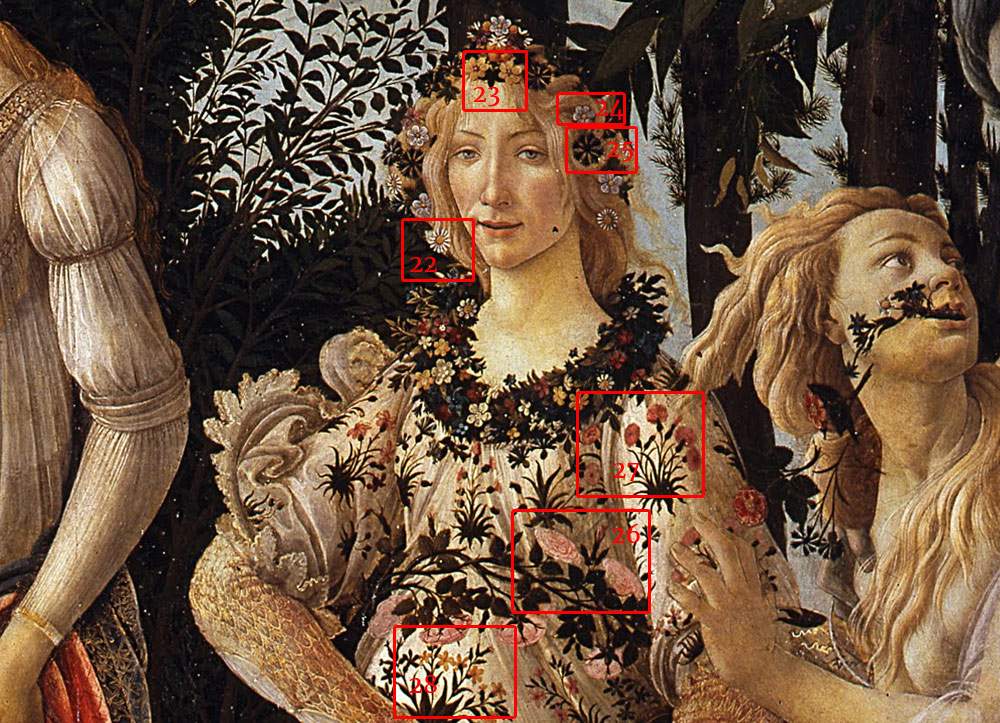

Moving to other areas of the painting, we find yet more new species. For example, between the feet of one of the Graces (the one on the left), we observe some forget-me-nots (or myosotis), which, as their very name suggests, are symbols of memory and remembrance, and again three flowers of nigella, another love symbol (as well as a plant known in antiquity for its medicinal properties), crocus (a symbol of coninugal love), and a plant of euphorbia: a flower, the latter, believed to be helpful to the eye, so it was thought it might be an invitation to the viewer to look at the work carefully. It is interesting to note the flowers coming out of the mouth of the nymph Chloris, who is being gherminated by Zephyrus: starting with those closest to the lips, we have three periwinkles, what is most likely a strawberry flower, two roses (but could also be two anemones) and two cornflowers. The strawberry and cornflower have already been mentioned. The periwinkle is symbolic of marriage bonding (from Latin vincire, “to bind”), while the anemone, being a flower whose life span is decidedly short, alludes to the fleetingness of pleasures and happiness. Again, on the right, above Zephyrus, we find a laurel plant, which alludes to the poem and to the commissioner himself (the plant’s Latin name, laurus, recalls the name Laurentius), and finally, in the lower right corner, we have a beautiful iris, the flower known as the “lily of Florence,” which grows wild in the countryside around the Tuscan capital and is depicted on the city’s coat of arms. In conclusion, it is worth dwelling on Flora’s hairstyle and robe, as both are adorned with additional wonderful floral species. Her hair, in particular, is decorated with daisies, cornflowers, strawberry blossoms and probably yellow anemones. On the robe, Guido Moggi recognized about sixty specimens, many of which are difficult to identify because they are somewhat stylized. We recognize well, however, some carnations, several roses, more cornflowers, and probably yellow wallflowers.

|

| Plants between the feet of the Graces. 14: Nigella; 15: forget-me-nots; 16: Crocus; 17: Euphorbia. |

|

| Plants coming out of Chloris’ mouth. 18: Periwinkle; 19: Strawberry; 20: Rose or Anemone; 21: Cornflower. |

|

| Laurel plant above Zephyr |

|

| Plants on Flora’s robe and foliage. 22: Daisy; 23: Anemone; 24: Strawberry; 25: Cornflower; 26: Rose; 27: Carnation; 28: Wallflower. |

|

| The iris flower |

What we have proposed in this article is but a quick overview of some of the species that are easier to identify even by those who do not know much about botany: but we are convinced that plant and flower enthusiasts will find something to delight in in front of the very lush Spring meadow in order to find all the other species that we have not accounted for here... !

Reference bibliography

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.