The Pisanello Tournament in Mantua. The story of the exciting discovery of a spectacular cycle

“One of the most important acquisitions in the field of art history in the 20th century”: this is how, and rightly so, the director of the Ducal Palace in Mantua, Stefano L’Occaso, defines the discovery of the Arthurian cycle that one of the greatest artists of the early 15th century, Antonio Pisano known as Pisanello, painted in a room of the sumptuous Gonzaga palace, and of which memory had long been lost. Pisanello’s unfinished wall paintings had been covered over over the centuries, first in the 16th century and then again in the 18th century, and the room had taken on a completely different appearance than it must have had in the early 15th century. The room had then been little used, partly because it was affected by a ceiling collapse a few years after the paintings were made: for these reasons, too, there are few sources that speak of this work. The discovery has allowed the return of one of Pisanello’s most significant cycles (as well as of his time), and from October 2022, on the occasion of the exhibition Pisanello. The tumult of the world, curated by L’Occaso himself, the Doge’s Palace, in a commendable operation, inaugurated an intervention that allowed the work’s correct legibility to be restored: a new lighting system, with warm light to enhance the gilding and details of the drawing, and a raised platform to return to the distance calculated by Pisanello (the current floor level is in fact 110 centimeters lower than it was in the early 15th century), bring the visitor to see a room as close as possible to how the great artist saw it.

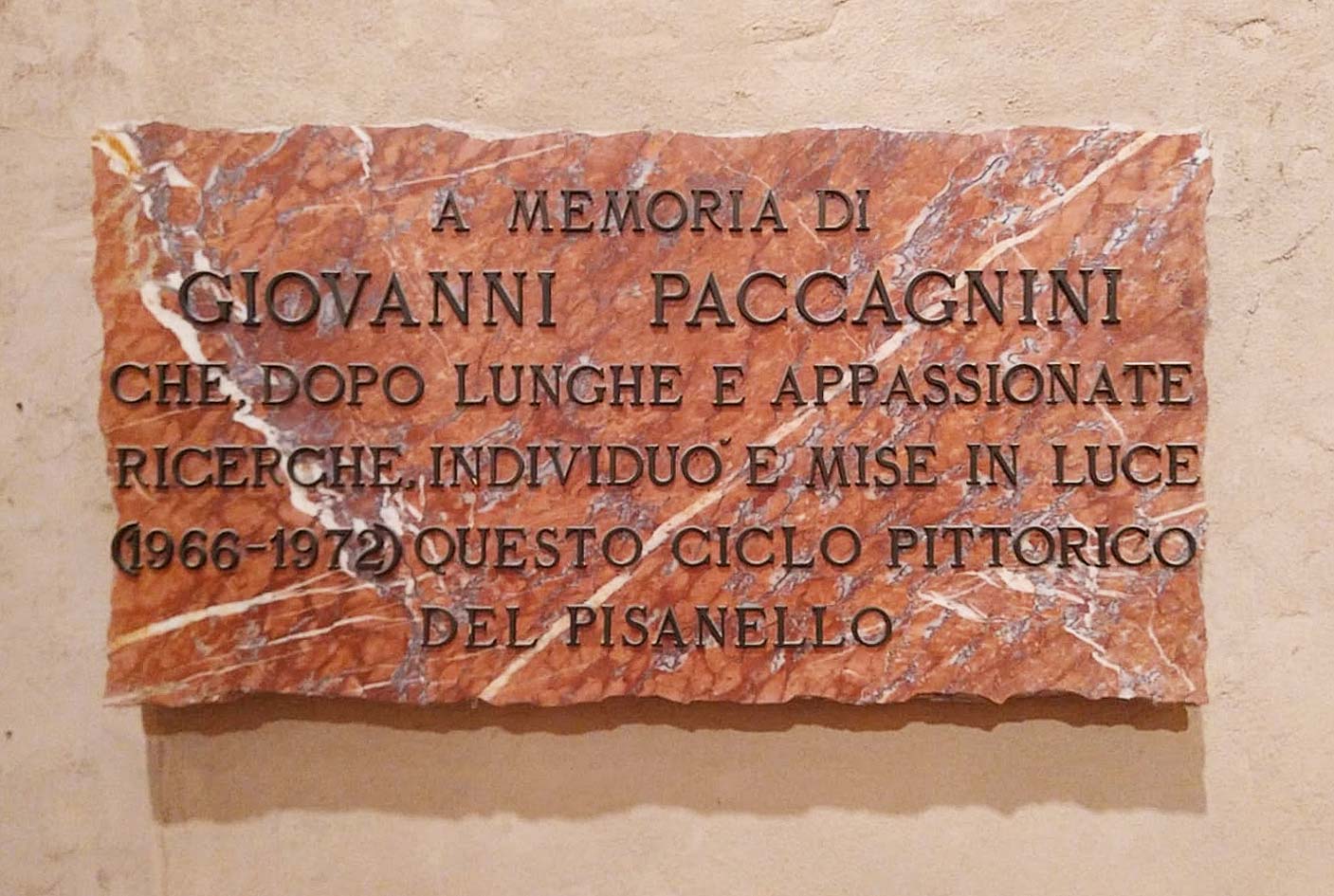

The discovery of the Arthurian cycle dates back to the 1960s: it took the intuition and tenacity of the then superintendent of Mantua, Giovanni Paccagnini from Livorno, to bring the paintings back from oblivion. That Pisanello had painted in the Ducal Palace had been known at least since 1888, when a document from 1480 was published in which a “salla del Pisanello” was mentioned inside the architectural complex. The importance of this room is certified by the fact that as early as the 15th century the name of the artist was used to identify it, which was completely atypical, extraordinary: usually, the rooms of a palace were named, L’Occaso explains, “after the subject of the paintings, the function, a certain color scheme, or the person who inhabited it.” The same room was also mentioned in a later-discovered correspondence dating from 1471-1472, in which the preparation for the stay in the palace of Niccolò d’Este, son of the Marquis of Ferrara, Leonello d’Este, was discussed. Paccagnini started precisely from this document: since between the 1950s and the 1960s the Castle of San Giorgio underwent major renovations, and since in 1480 the “Pisanello room” was found to be unsafe, the superintendent guessed that the room with the paintings should be sought in the Corte Vecchia, where the Gonzagas lived from 1328 to 1459 before moving to the Castle. Paccagnini assayed several rooms and then finally focused on a hitherto neglected building on two floors: it was the one where Isabella d’Este had had her apartment opened on the first floor in 1519. The room in which Pisanello had worked, which later became the “Hall of the Dukes” because it was later decorated with an eighteenth-century frieze with images of the dukes of Mantua, was on the upper floor, adjacent to the Guastalla apartment, and close to the row of tapestry rooms.

What presented itself to Paccagnini’s eyes was, writes scholar Monica Molteni, “a large room with banal neoclassical facies, apparently devoid of elements that would encourage the search for fifteenth-century pre-existences.” The deterioration the room had undergone over the centuries, however, had brought to the surface the remains of a late 14th-century geometric decoration, found in the attic, while the removal of plaster from the building’s exterior facades had made clear the structure’s 14th-century origin. Paccagnini therefore initiated investigations underneath the neoclassical decorations: the removal of the plasters allowed the discovery of sinopites (the preparatory drawing traced directly on the wall) that revealed Pisanello’s unmistakable style. Thus, the dismantling of the neoclassical panels and the tearing down of the frieze (which was later relocated elsewhere) was ordered: “the most stringent and definitive findings,” explains Molteni, “were on the short wall of the side of the Hall of the Popes, where the removal of the eighteenth-century plaster and the underlying remains of sixteenth-century painting left a surface covered with a thick layer of grime to emerge, which, once cleaned, revealed the presence of the heraldic frieze and parts of figures pertinent to the underlying battle scene, whose Pisanello autograph work was immediately evident.” The restoration work was entrusted to restorers Ottorino Nonfarmale and Assirto Coffani, who had been at work since 1963: it took a year of work to bring to light Pisanello’s paintings, which were cleaned and consolidated, so that at the end of the intervention the Tuscan artist’s work could be said to have been recovered, although it was necessary to wait until 1972 for the presentation of the discovery, which was not announced until 1969, however. In fact, work was necessary to secure the environment, especially to ensure the paintings found the optimal conditions of preservation, since it was a room that, as mentioned, had experienced strong phenomena of degradation over the centuries. It was an undertaking that was anything but easy: in fact, even Pisanello’s paintings and sinopites were torn off (with enormous wooden rollers that are still preserved in the storage rooms of the Doge’s Palace, and which will be on display) in order to transfer everything onto a double layer of canvas that was in turn placed on movable supports. Once the work was finished and the discovery announced, there then followed the study that led to the publication of the monograph on the cycle in 1972.

The room is painted on all sides with a single, large scene depicting, seamlessly, a tournament of knights told in different stages, although not all the walls present the same degree of completeness: on the northeast wall, the one on the left as one enters, the sinopia has survived almost exclusively, conducted, however, with an accuracy suspicious for a preparatory drawing, a subject definitely important for understanding part of the history of this cycle, as we shall see below. On the adjoining wall, however, survives a large composition executed in mixed media, the first to be completed: a large composition that was meant to give the impression of being a large precious painting, a splendid tapestry, since “Pisanello’s clients,” write Vincenzo Gheroldi and Sara Marazzani, “also perceived the painting as a large luxury object,” as can be seen by observing the presence of many expensive materials in this completed part (for example, the harnesses of the horses made of gilded tin, and added to the pictorial layer: these were precise requests of the patrons, aimed at flaunting the economic value of the whole). The sinopia of this finished scene, moreover, has also been recovered and is displayed in the adjoining room.

The scene is to be read from the southeast wall in a counterclockwise direction: an excited tournament takes place on the wall opposite the one from which one enters the room, after which one turns one’s gaze to the long wall to the left where a number of wandering knights are depicted, caught during their exploits. It was scholar Valeria Bertolucci Pizzorusso who unraveled the enigma of the cycle’s iconography: some of the knights-errant depicted in the sinopia near the room’s fireplace in fact bear their names, Celtic, and written in Gothic characters (Bohort, Sobilor, Arfassart, Sardroc). They are characters related to an episode in Lancelot du Lac, a medieval French novel in which the exploits of King Arthur’s knights were recounted. The episode in question tells of the tournament organized by King Brangoire at the chastel de la Marche: Bohort, Lancelot’s cousin and the best knight among the participants, takes part in the tournament. Next to the tournament scene we see depicted the banquet that is given at the end of the tournament to celebrate the winner: Bohort, as the first runner-up, chooses a damsel to give in marriage to the other twelve best knights, but he rejects the king’s daughter, who would have been his due, because she had taken a vow of chastity in view of the quest for the Grail. However, the princess, willing to unite with Bohort, will convince her wet nurse to enchant the hero with a spell in order to spend a night with him: a son, Hélain le Blanc, destined to become emperor of Constantinople, will be born of the union.

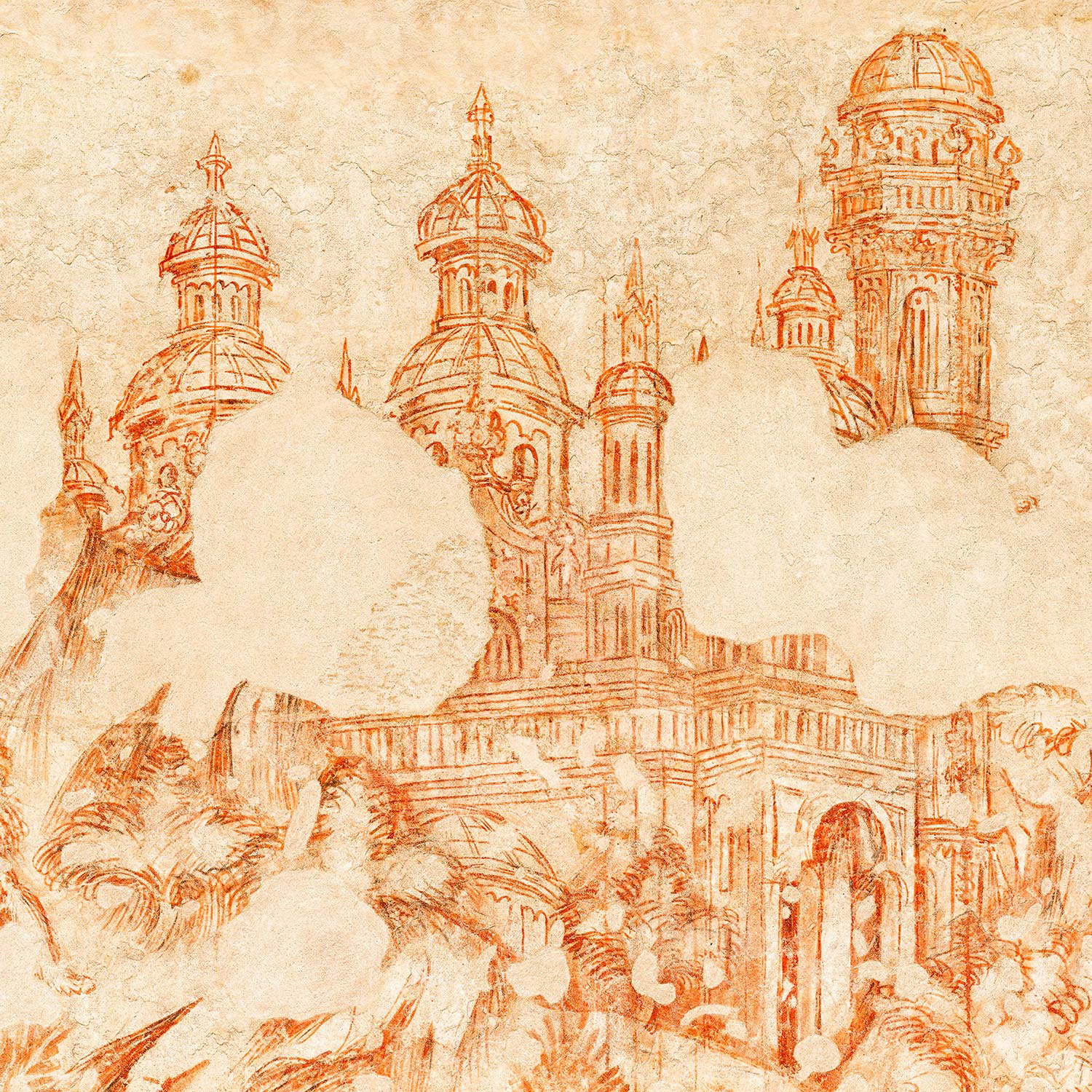

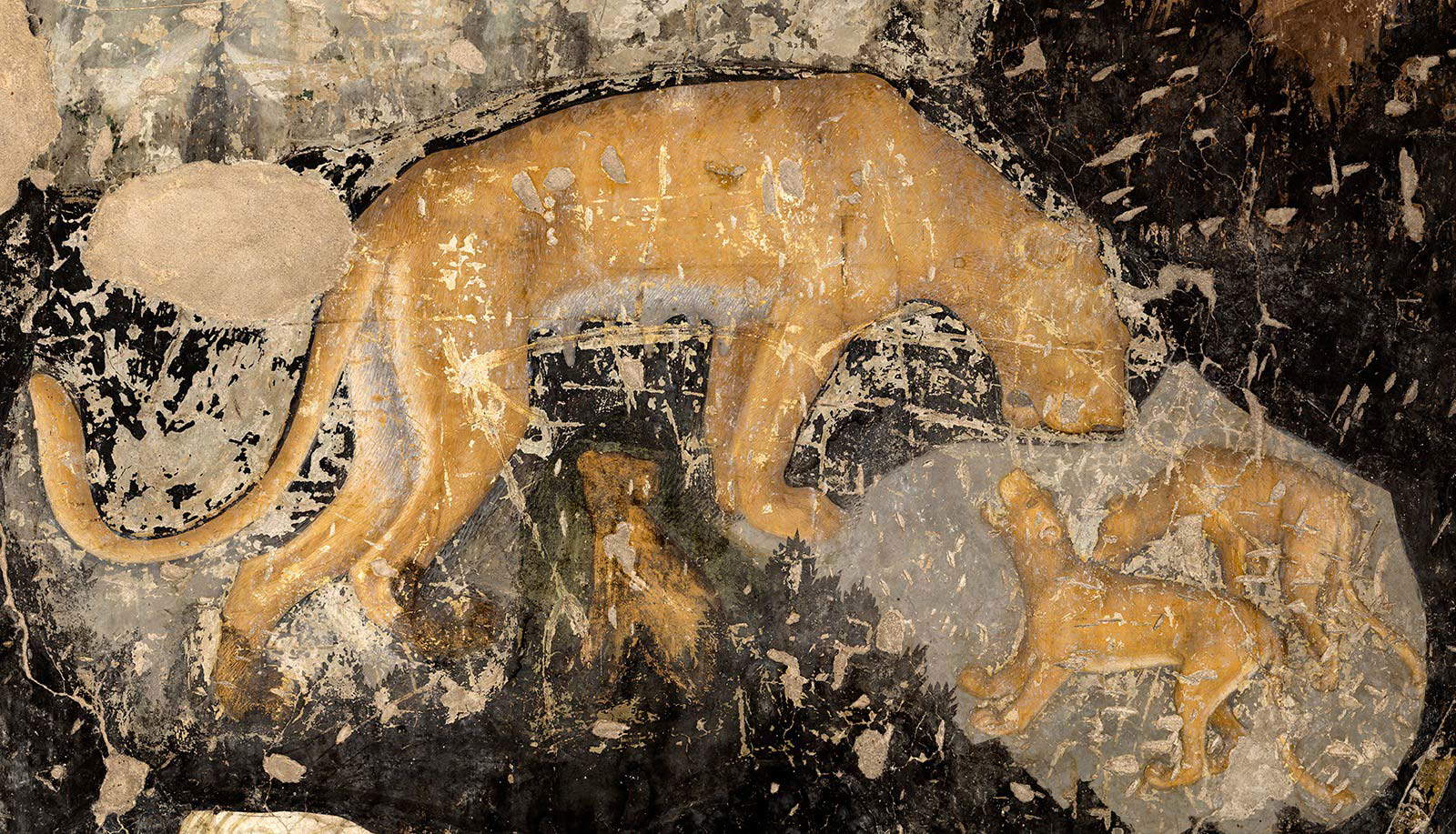

Observing the scene painted by Pisanello, one almost has the impression of witnessing a real fifteenth-century tournament, a custom quite common in Italy at the time, however much the gaps hinder a full reading of what the artist depicted on the walls of the Ducal Palace. “Perhaps the most striking thing about the tournament illustrated by Pisanello,” Andrea De Marchi has written, “is that it has no delimited place, it spreads out in all directions, and in it a chaotic mixture apparently reigns, so that it is hard even to tell who is fighting and against whom, riding to the lance or in hand-to-hand combat to the sword, who is preparing, who has already fought. Coexisting, it seems to be understood, are distinct temporalities, with a deliberate jarring effect.” In the tournament scene, the upper left is dominated by knights who seem to be watching the fight raging before them: knights in armor fight, spears break, there are horses running, unseated combatants succumbing, others lying already defeated, one below about to fall from his steed. Finally, on the right, one will notice the unusual presence of a lion facing the relative and, further down, a lioness with her cubs, while still further below one will glimpse a dwarf dressed in the tricolor. The centerpiece of the scene, the point where we see the broken spears flying between the confronting horsemen, is slightly off-center to suggest to the viewer that the figuration continues on the next wall: there we find a group of horsemen, including one looking toward us, wearing broad headgear. This blond knight is supposed to be Bohort himself, the winner of the tournament. Above him, we see three figures, portrayed with lively taste for individual characterization: a mature brown-haired man, a Moor, and a young blond man. In the synopias we find the women’s box, a castle, and finally a lush landscape filled with carefully drawn woods and castles, where it is not unusual to find animal presences and where the knights, identified by the inscriptions with their names, move about.

Knights

Knights

The

The

Movement, depth, and precision in description are some of the elements that guided Pisanello in the creation of his paintings, which are loaded with meanings beyond those that emerge from an immediate reading of the work. “Rarely in painting,” De Marchi goes on to write, “has such a deflagrating reflection on human violence been initiated, and the bumpy setting, subdued within it by contradictory tensions, poignantly highlights the icastic force of so many frames, of so many well-known details.” For the Tuscan scholar, Pisanello was faced with a double challenge: to execute credible, realistic paintings, capable of accurately conveying the natural phenomena that Pisanello observed and was able to render like no other painter of his time, while at the same time offering visitors to this setting a “synaesthetic perception.” This, then, is why these paintings appear so enveloping to us, for it almost seems as if we can hear the horses, hear the cries of the tournament, the hubbub of those observing, seem to imagine the dust rising: the ability to arouse this kind of sensation was, moreover, already recognized to him even by his contemporaries. Also of interest is the parallel established by De Marchi with the scenes of the Battle of San Romano painted by Paolo Uccello for Leonardo di Bartolomeo Bartolini Salimbeni: the Florentine artist had painted “warlike events as if they were tournaments of chivalry,” while the Pisan, on the other hand, had painted a tournament in a crude and brutal way, as if it were a battle. On the one hand, a battle painted for a Florentine notable who, although he had participated in the Lucca campaign that Florence undertook against Milan and Siena, was not a professional soldier, and on the other hand a tournament painted for a family well accustomed to military life, having moreover Gianfrancesco himself for a long time pursued the profession of captain of fortune, securing himself conspicuous fortunes. Innovative is theorganization of space: the artist opts for a dynamic point of view, and several elements are reminiscent of the St . George and the Princess in the church of Santa Anastasia in Verona (the very high horizon, for example, or the crowding of buildings, and then again, writes L’Occaso, “the same care in the architecture, traced in Mantua by axonometric lines and taken care of in the smallest detail, which close up the sky, the same the use of figures that furrow the space in depth”).

Some elements of the cycle help shed light on the commissioner’s name: the family of lions, the Great Dane dog with its head turned backward in the sinopia where the women’s box is depicted (it is immediately below), a symbol of fidelity, and again the flowers such as daisies and marigolds symbolic of the Gonzaga family, and the figure of the clapper, or the “dwarf” in tricolor robes (white, red and green were the colors of the family that ruled the fortunes of Mantua). Initially, a late date for this cycle had been proposed: Paccagnini thought that Pisanello had waited on it for Ludovico II Gonzaga from 1447 until 1455, the year of his death, a circumstance that would explain why the cycle is unfinished. However, the reading of the emblems just described made it possible to more correctly assign the commissioning of the cycle to Ludovico II’s father, namely Gianfrancesco Gonzaga (who has also been identified in the knight with the wide headdress occupying the right-hand corner of the side wall: the one in which Bohort’s image is also wanted to be seen). On the reason for the choice of the subject, the scholar Michela Zurla writes as follows, recalling its links to the context of Gonzaga image politics: “The value that the theme of the search for the Grail takes on in relation to the cult of the relic of the Precious Blood of Christ preserved in Mantua, a cult toward which the Gonzaga showed such deep devotion that they included the depiction of the reliquary in some of their own coins, has been stressed on several occasions.” It is precisely the choice of Bohort, according to the studies of Ilaria Molteni and Giovanni Zagni, that takes on a very relevant significance due to the fact that, after finding the Grail, he was the only one of Arthur’s knights to return to the court “and to have a descendant, thus candidating himself as an ideal progenitor for the Gonzaga family” (so Zurla). However, we do not know when the cycle was made: having discarded Paccagnini’s hypothesis that imagined an execution in the extreme stages of Pisanello’s activity, various theories have been put forward. For Gian Lorenzo Mellini and Anna Zanoli the cycle was executed between 1436 and 1444, a dating with which Ilaria Toesca also agrees. For Miklos Boskovits we are shortly after the Roman sojourn of 1431-1432.

Knights engaged in the

Knights engaged in the Knights engaged in

Knights engaged in

Precisely in shedding light on the dating, sinopites could be useful. Recently, the scholar Alessandro Conti has proposed that it is the result of deliberate and well-calibrated choices to have carried out high-quality finishes on the sinopias. The fact is that, at a certain point in its completion, the cycle was at too early a stage of work to be finished in time to manifest itself to some important personage who would be housed in the hall, and it was therefore necessary to complete it temporarily. The event for which this was necessary was probably, according to Conti, the visit to Mantua of Emperor Sigismund of Luxembourg in 1433. “Lords in their infancy such as that of the Gonzaga,” De Marchi further explains, “were hanging by the thread of imperial legitimacy, and of paramount importance was the prospect of being able to host the king of the Romans and king of Bohemia, who had descended to Italy from Basel in the fall of 1431.” Pisanello could therefore have painted the Arthurian cycle either before or after his Roman sojourn, at any rate in time for the visit of the emperor, who granted the title of marquis to Gianfrancesco Gonzaga on May 6, 1432, in Parma, and on September 22, 1433, in Mantua, in a public ceremony renewed his concession. The emperor’s visit to Mantua was an exceptional event, in view of which the decoration of the hall necessarily had to be ready: it is therefore possible to suppose, according to the chronology proposed by De Marchi, that the artist may have begun the work before his momentary move to Rome, where on July 26, 1432 he obtained a safe-conduct from Pope Eugene IV to leave the city, and consequently he may have returned to Mantua to attend, between 1432 and 1433, to the second part of the work, that of the sinopias and the stage (or even to the entire decoration of the hall, we do not know for sure).

We do not know the reason why Pisanello abandoned the work. We do, however, know quite well the events that the hall he decorated went through before falling into oblivion. On December 15, 1480, court architect Luca Fancelli wrote to Marquis Federico Gonzaga to inform him of the collapse of part of the hall’s ceiling: Fancelli therefore worked to secure the room, also removing the parts of the ceiling that had not collapsed but remained unsafe. Probably, before the collapse, rooms had been made on the upper floor that had somehow encumbered the ceiling. In any case, after 1480 nothing more is known of Pisanello’s paintings: according to the chronology reconstructed by Stefano L’Occaso, in 1579 the floor level was lowered, the original windows plugged, the windows still visible today were opened, and the fireplace was added. The hall, at that time called the “archers’ hall,” was then in a state of severe deterioration, and was entirely restored by Pompeo Pedemonte, who covered it with corami, while later, in 1595, it was entirely painted with faux marble by Domenico Lippi and collaborators, at the time when this wing of the palace was to serve as the apartment of Duchess Eleonora de’ Medici, wife of Vincenzo I Gonzaga. Later, in 1701, the frieze with the portraits of the dukes was added, and the room thus became known as the “hall of the dukes. ”Finally, between 1808 and 1812, the frieze was restored and the room took on the neoclassical appearance that it maintained for more than a century. That is, until a superintendent sensed that beneath those rigid and banal squares there must be something far more significant.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.