A collection that is widely described as “unique in the world”: that of the Museo delle Sinopie in Pisa, consisting entirely of sinopites. One could define sinopia as the preparatory drawing of a fresco: it is one of the least known elements of medieval and Renaissance Italian art, but these are extremely interesting realizations since they often constitute the only evidence of the early stages of the realization of a fresco, as well as the only records of an artist’s graphic work. The term “sinopia” derives from the name of Sinope, an ancient Greek colony located on what is now the Turkish Black Sea coast, now a modern industrial center and once famous for its red-brown pigment, the “earth of Sinope,” used by medieval artists. It was used in a compound made simply with this pigment and water: the rust-colored result was used to draw detailed sketches of the final work that were executed directly on the walls to enable artists to plan the composition, proportions and details of the frescoes.

First, the artist would lay a layer of plaster on the wall, about a centimeter thick: this was thearriccio, a layer that was left purposely rough so that subsequent layers would adhere better. It was precisely on the arriccio that the sinopia was laid. At first the artist would sketch it out in charcoal to create an initial outline, after which, when he was satisfied, he would go over it again with red earth and better define the details, such as the characters’ expressions, faces, drapery, and light effects. The sinopia, which was the first translation on the wall of a drawing that originated on paper, served as a kind of guide for the artist: once finished, the artist would lay down a new layer of plaster, called “intonachino,” which was smooth in that it served to receive the color. The intonachino should be imagined as a kind of transparent veil, which thus allowed a glimpse of the sinopia so that the artist could follow the trace, going on to paint it with the color that was thus spread over portions of the plaster that had to remain wet, which is why the work was divided into “days,” that is, parts of the plaster that the artist painted that corresponded to individual days of work (hence the name).

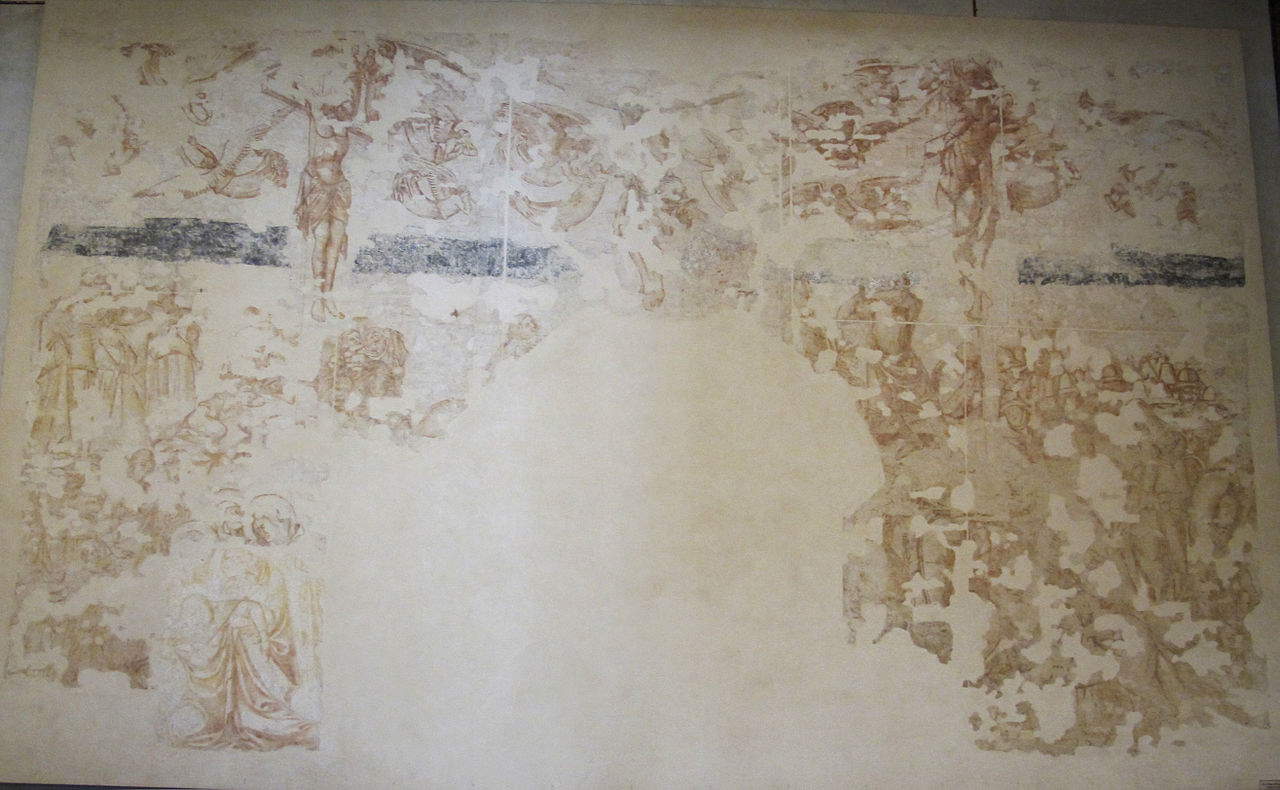

The Pisa sinopites represent a unique case in the world of sinopites for an entire cycle of frescoes that have been preserved and have then been protected and enhanced for public display in order to tell the story of this fascinating and little-known aspect of medieval art.In the halls of the Museo delle Sinopie, therefore, an extraordinary chapter of art history unfolds, revealing valuable details about the artists’ creative processes and the culture of ancient times. However, the discovery of the Pisan sinopias occurred under dramatic circumstances. During World War II, an American bombing raid on July 27, 1944 severely damaged Pisa’s Camposanto Monumentale, one of the most emblematic structures in the Piazza dei Miracoli complex. A shell, in particular, hit the roof, caused a fire and caused severe damage, in several cases irreparable, to many frescoes from the walls. Damage to the painted surface was suffered by works by 14th-century Pisan and Florentine artists depicting stories from the life of St. Ranieri, the city’s patron saint, that of Job, and the same fate befell Francesco Tarini’s Crucifixion . Minor damage was suffered by Piero di Puccio’s Stories of the Creation . Buonamico Buffalmacco’s spectacular frescoes of the Triumph of Death and the Thebaid also suffered severe damage to the support, since the plaster had been laid over an incannicciato fixed to the wall with nails. The most serious damage, on the other hand, was suffered by Benozzo Gozzoli’s Old and New Testament cycle: some of the stories in the cycle were literally reduced to crumbs.

The only way to ensure the preservation of the one that had suffered the least damage was to detach it by the method of tearing, a technique for removing a fresco that allows the most superficial part of the painting, about two or three millimeters thick, to be removed. The operations went well: as early as 1948, architect Paolo Sanpaolesi could testify that the first tears, those of the frescoes of the Triumph of Death and the Thebaid and of five of the most damaged stories of Benozzo Gozzoli’s cycle, “have been perfectly successful, despite seasonal difficulties and those of various kinds inherent in the species of the frescoes and their conditions.”

Precisely because of the characteristics of this technique, which does not affect the wall like other older techniques (e.g., massello, also known as “stacco a massello,” which consists of removing large portions of the wall), it was possible to discover the sinopites of the frescoes that decorated the Cemetery. This unexpected discovery gave scholars access to a hidden artistic treasure that could offer a new perspective on the working methods of medieval and Renaissance artists, at least until the mid-15th century, a time from which sinopia began to be progressively replaced by the more practical technique of spolvero: in fact, this was the largest known nucleus of sinopias at the time. The discovery of the sinopites added value to Pisa’s artistic heritage and shed new light on the techniques and artistic practices of the past.

Later, the sinopites were also removed from the Cemetery, mainly for reasons of conservation, since these are works easily subject to deterioration, and then also because a dedicated museum would have made it possible to better enhance this heritage. The removal of the preparatory drawings took place in 1979, and the conservation of these works undoubtedly posed a significant challenge for restoration experts.

After their discovery, it was necessary to carefully remove them from the damaged walls and transfer them to new supports to ensure their long-term preservation. This site, wrote art historian Luca Ciancabilla, represented “a page of considerable importance for the history of restoration and conservation of the ancient Italian pictorial heritage,” since it was “a veritable experimental laboratory for the practice of extraction, for the first time interested not only in the detachment of the frescoes (which were placed on safer eternit instead of on the now obsolete canvas), but also in that of the underlying sinopites, which were also subject to the same conservative and cognitive attentions, as well as, when the work was finished, museographic and therefore exhibition.” This was an absolute novelty: “never during the three centuries that had marked the technical and historical evolution of the practice of extraction had an attempt been made to also bring to light the drawing underlying the mural painting. In Pisa, the bombings had not only caused a disaster that had been remedied through the capillary detachment of the paintings involved, but had favored the discovery and thus the consequent transport of the sinopites, causing those particular testimonies of ancient art to become, even in other Italian realities, the object of new and never-beaten artistic studies,” since the sinopia was able to show the procedure followed by the authors of the frescoes. The Pisan experience was therefore unprecedented and pioneering: “that site,” Ciancabilla writes again, “would in fact mark forever the following decades by opening in a clear and decisive way the most important and generalized campaign of removal of frescoes and sinopites that our country has known in its recent history; a phase that represented the culmination of trust in that particular conservation technique.”

To make the most of the sinopias, it was planned to display them in a specially established museum. For the location, the Spedale della Misericordia, also known as the Spedale Nuovo, ancient hospital designed in the 13th century by architect Giovanni di Simone (to whom we also owe the work on the first building site of the Camposanto), who also built, between 1257 and 1286, the church and the hall of the Pellegrinaio degli Infermi, which was used to assist not only the sick and the poor, but also pilgrims who passed through Pisa and had needs. In the 1970s the structure was no longer in use as a hospital and was the subject of an intervention aimed at making it the new home of the museum. The building was restored between 1975 and 1979 to a design by architects Gaetano Nencini and Giovanna Piancastelli, after which, in 1979 itself, the Museo delle Sinopie di Pisa was inaugurated, now an essential stop for art and history enthusiasts during a visit to the city. The museum offers an exhibition itinerary, also strengthened by the 2005 refurbishment and new lighting designed by the Targetti company, that allows visitors to admire the sinopias of the Monumental Cemetery up close, providing a unique insight into the creative processes of medieval and Renaissance artists that is unparalleled elsewhere. The sinopites on display in the museum are accompanied by information panels that explain the historical and artistic context of each work, so that visitors can better understand the role of sinopites in the creation of the frescoes and appreciate the skill of the artists who executed them. This technique offered artists flexibility, allowing them to make changes during the process of making them. In addition, the sinopites reveal the changes and corrections made by the artists, providing valuable information about their methodology and creative intentions.

As mentioned, all of Pisa’s sinopias come from the Camposanto Monumentale: built in the 13th century, the Camposanto is known for its frescoes, which adorned the building’s interior walls. These frescoes represent a masterpiece of medieval and Renaissance art, with scenes of religious subjects. Prominent among the frescoes are those by Buffalmacco, Benozzo Gozzoli, Andrea Bonaiuti, Spinello Aretino, Taddeo Gaddi, Antonio Veneziano, and Piero di Puccio: the discovery of the sinopias of these artists made it possible to admire their skills in drawing and composition, revealing in a more pronounced way the differences between the different painters, since the execution of the frescoes inevitably led to a greater stylistic uniformity, while from the sinopias it is possible to better appreciate the individual personalities. For example, the sinopias of Benozzo Gozzoli, one of the last artists to attend to the decoration of the Camposanto, sometimes show great precision in the rendering of figures and landscapes, but often his drawings were incomplete, because it was enough for him to fine-tune a few isolated figures over a perspective outline to realize perfectly how the finished work would turn out. Others, however, such as Buffalmacco and Francesco Traini, preferred to have a more complete picture, even within the economy of signs that generally characterizes sinopias (there was no lack, however, of elements drawn with complex hatching and of careful studies of chiaroscuro effects, as can be seen in the sinopias of Buffalmacco’s Thebaid ).

The Pisa sinopites have left a lasting legacy in the field of art history and restoration. They have stimulated research and innovation in the field of conservation techniques, helping to develop more effective methods for preserving ancient works of art. They have inspired greater attention to artists’ preparatory drawings and sketches, recognizing their value as works of art in their own right, often offering more guidance than finished works. This has led to a reassessment of the role of drawing in artistic practice and a more widespread and consistent appreciation of the creative processes that lead to the creation of works of art. This is why the Pisa sinopites represent a fascinating, though still little known, chapter in Italian art history. Their discovery and preservation have made it possible to unlock the secrets of the creative process of medieval and Renaissance artists. And the Museo delle Sinopie, with its unique collection, continues to preserve and exhibit these extraordinary works, which are not only an invaluable artistic treasure, but also an important cultural testimony.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.