The Palazzina di Caccia di Stupinigi, the Savoy residence of unexpected wonders

What is a deer doing on the dome of one of Piedmont’s most fascinating Savoy residences ? Imposing and regal with its stage of well-branched antlers, the animal that has become the symbol of the Stupinigi Hunting Lodge stands out in the sky as if it were a guardian, dominating the large Nichelino complex at its center, ten kilometers from the central Piazza Castello in the Piedmontese capital (to which it is joined by a straight line), to highlight and remind us what the residence’s main purpose was. In fact, the Palazzina on the outskirts of Turin was built to be the place from which the hunting parties of the House of Savoy started and ended, and secondly, when it was not time to go to the surrounding countryside to engage in hunting activities, it was here that the royal family liked to organize large parties and carry out the most varied leisure activities. The deer sculpture that stands today on the Stupinigi Hunting Lodge is a copy, but in the past there was precisely the original bronze, copper and gold leaf sculpture made by Francesco Ladatte in 1766, which can still be seen after the ticket office, in the so-called “Deer Room.” But this, although it has been taken as a symbol of what could be called the “residence of wonders” for various reasons, was not in the history of the Palazzina the only animal, because it is true that the menagerie of Stupinigi was born in the 18th century for thebreeding of deer and fallow deer destined for royal hunting parties, later transferred to the Vicomanino farmstead, but in the nineteenth century Stupinigi began to accommodate the exotic animals that were donated to the Savoy family or purchased by them. Initially distributed in the farmhouses of the Palazzina, these animals were later housed in the San Carlo estate, and this menagerie became so important that it was considered the first Italian zoo. Over time, the animal collection was enriched with many species, including even rare mammals such as kangaroos (which had a sad fate because in one winter they all died of the cold), monkeys, parrots, ostriches, a seal, a marabou, peacocks and even a Barbary lion and an American migratory dove. Some of these specimens, now naturalized, are still on display in the Regional Museum of Natural Sciences.

The animals received as gifts include in particular an Indian elephant that was given the name Fritz. It was donated in 1827 by the Viceroy of Egypt Mehmet Ali to Charles Felix, with a view to sending exotic animals to European rulers. The massive pachyderm departed from Alexandria, Egypt aboard a Sardinian Navy steamer, crossing the Mediterranean. During the voyage it became necessary to stop in Sardinia because of his restless temperament: in fact, Fritz could hardly stand sailing despite the fact that a sort of hut had been arranged for him in the middle of the boat. When he arrived in Genoa, he spent the winter in the dock, as the cold temperatures in Stupinigi were not suitable to house him. Only in May did he begin his move to Piedmont. He faced the journey on foot, escorted by carabinieri and accompanied by a wagonload of food specially selected for him. He traveled mainly at night, so as to prevent crowds from agitating or disturbing him, since his temperament was not well known. In June, Fritz was welcomed at the Palazzina di Stupinigi: he was the only animal in the menagerie to be housed inside the complex, rather than in the menagerie of the San Carlo estate. In anticipation of his arrival, suitable spaces had to be arranged: the semicircular stables on the east side were chosen, where a large stall was made for resting hours, but the elephant also had access to the courtyard for strolling and could also cool off in a large circular pool equipped with a slide, specially dug for him. He also learned to independently use a pump to quench his thirst without the janitor’s intervention. Fritz lived at Stupinigi for about twenty-five years, until he was killed in 1852. The people of Turin also had great affection for him and often went to admire him to watch him perform his exercises. His dietary and behavioral habits were documented by the keeper of the menagerie and, in particular, by the director of the Royal Museum of Zoology of the University of Turin, who followed his life closely and drew up a detailed manuscript, which is still preserved in the university department’s library. With the accession of Victor Emmanuel II to the throne, however, Fritz’s fate took a tragic turn. Left without his janitor, to whom he was deeply attached, he became increasingly difficult to manage. The king, moreover, did not tolerate the huge expenses required for his upkeep. These factors led in 1852 to his killing. The king donated his remains to the Museum of Zoology at the University of Turin, where his skin and skeleton were prepared for taxidermy to come on display to this day in the Regional Museum of Natural Sciences. Part of his tusks, which were cut off while he was still alive because of their irregular growth, was instead used to make a crucifix, which is now kept in the chapel of Agliè Castle. In addition, numerous studies in the field of histology and mammalian retina were carried out on his remains. In 2014, the Regional Museum and the Stupinigi Hunting Lodge organized an exhibition dedicated to the menagerie, in which Fritz played a central role, and for the occasion, a resin copy of the elephant was created, which was then placed in the so-called Elephant Courtyard of Stupinigi.

Built starting in 1729 to the design of one of the greatest architects of the eighteenth century, Filippo Juvarra, at the behest of Victor Amadeus II in the middle of a vast hunting reserve on the land of Emanuele Filiberto’s first donation to theOrder of Saints Maurice and Lazarus (1573) and then until the end of the eighteenth century enlarged at the behest of Charles Emmanuel III by Benedetto Alfieri, the Palazzina di Caccia encloses many other marvels, starting with the large central Hall with an elliptical plan designed as a spectacular room intended for festivities that constitutes the fulcrum of the entire complex, since from here the four arms projected toward the gardens that give the Palazzina its St. Andrew’s cross shape. Conceived by Juvarra as a grand stage setting, in which optical illusion becomes the protagonist, blending architecture, painting and decoration into a single visual spectacle, the hall lit by large windows is spread over two levels and a balcony runs at mid-height; concave and convex balconies that were used to accommodate musicians during festivities. The brothers Domenico and Giuseppe Valeriani were responsible for trompe l’oeil frescoing the room with painted faux architecture framing episodes from the myth of Diana. In addition to the frescoes, the furniture and ornaments were designed to complement the setting of the hall. Notable among these are the paracamini painted by Giovanni Crivelli in 1733 with hunting scenes and the thirty-six sconces carved with roe deer heads, by Giuseppe Marocco, placed along the walls: carved between 1733 and 1737 by Marocco, they were then gilded with layers of gold leaf by Giovanni Carlo Monticelli on the details, such as garlands, leaves and shells. Inside niches above the entrances are also four marble busts, made in 1773 by brothers Ignazio and Filippo Collino, depicting Ceres, Pomona, Naiad and Napea, gods and nymphs related to the earth, fruits, waters and woods, symbolizing prosperity and abundance. In the center of the vault, however, is depicted the great Apotheosis of Diana, goddess of the hunt: she is seen on a chariot in the clouds, surrounded by her companions and her faithful hounds. Other mythological episodes are depicted in the four monochrome ovals placed in the spandrels of the vault.Hunting art, the central theme of the residence, is celebrated in every detail, in perfect harmony with Filippo Juvarra’s design, including in the side galleries and oculi that simulate openings to the sky, where cherubs and nymphs chase partridges and peacocks.

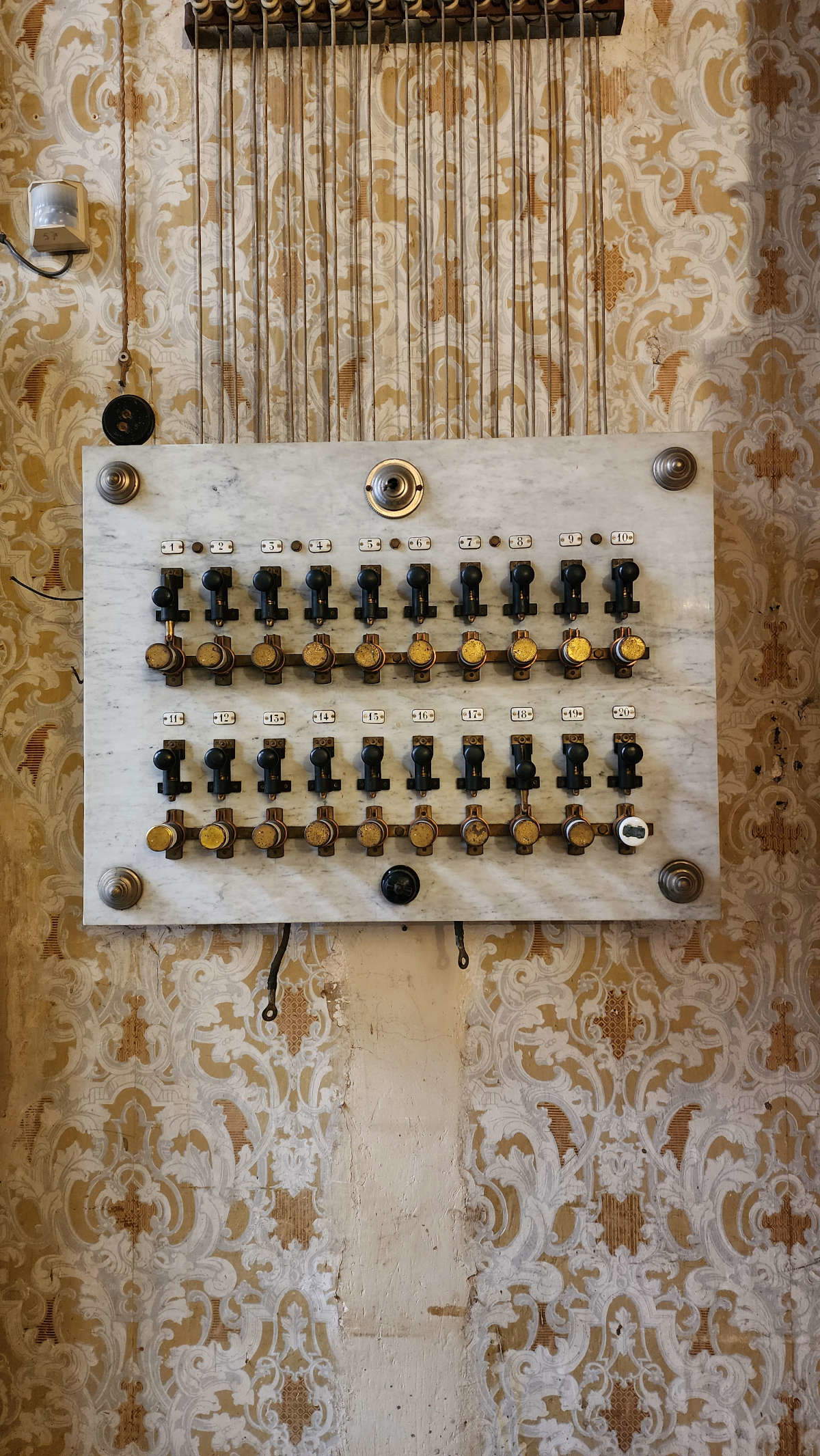

The large central hall is then surmounted by an inverted boat dome, which can be reached by climbing a narrow spiral staircase of fifty steps (not accessible to people with disabilities and strongly discouraged for those suffering from claustrophobia or vertigo) during special guided tours by appointment: having arrived at the top of the Juvarra dome, just below the deer, two spectacular views open up before our eyes, the interior view of the complex wooden structure that supports the dome and the exterior view of the beautiful 360-degree panoramic view that stretches along a visual axis all the way to Turin. With extraordinary guided tours, always by reservation, it is also possible to walk through the corridors and through the hidden passages that were used by servants to move discreetly among the rooms of the residence, until reaching the painting of the automatic bells, a rare example of the sophisticated calling system of the time.

Other marvels include the chinoiserie of the Game Room in the east apartment, entirely decorated by the Viennese-born painter Cristiano Wehrlin, who was commissioned in 1764 to paint the walls, doors, and overlays with oriental-style lake landscapes that include birds and plants under a basin ceiling decorated as if it were an arbor on which exotic birds are perched, and graceful Chinese toilets. Behind the doors, in the Hunting Room and the Bedroom in the King’s Apartment, are pregadio with kneelers by the famous cabinetmaker Pietro Piffetti; in theAntechamber of the Queen’s Apartment is one of the most important frescoes in the Palazzina, the Sacrifice of Iphigenia, painted in 1733 by the Venetian painter Giovanni Battista Crosato, on the vault: taken from Greek mythology, the episode is related to the celebration of the goddess Diana, who saves Agamemnon’s young daughter from the sacrifice made at the hands of her father by replacing her with one of his hinds. And then again, the furniture with precious mother-of-pearl inlays by Luigi Prinotto and Pietro Piffetti that can be admired in the Bedroom of Queen Margherita of Savoy, the last inhabitant of the Hunting Lodge, and the precious carved and painted blue and white cabinet , visible in the Bonzanigo Room, which was formerly attributed to the Piedmontese carver active from the second half eighteenth century until the early nineteenth century Giuseppe Maria Bonzanigo, while later studies attributed it to another coeval artist, Francesco Bolgiè.

The aforementioned hunting theme shared throughout the residence is present, for example, in the still lifes of game, fish and fruit and in the figure of a hunter leaning over a mock balustrade in the Hall of the Squires, as well as in the cycle of thirteen canvases in the same room made by Vittorio Amedeo Cignaroli with hunting subjects commissioned by King Charles Emmanuel III around 1770, in which the different phases of deer hunting are depicted in great detail, but also in the Chapel dedicated to Saint Hubertus, patron saint of hunters, designed in 1767 by architect Ignazio Birago of Borgaro: the saint is here the protagonist of the altarpiece created by Vittorio Amedeo Rapous.

The interiors of the Palazzina di Caccia represent an extraordinary expression of Italian Rococo, characterized by elegant lacquers, gilded stucco and refined furnishings. The residence still preserves original furnishings and houses the Museum of Art and Furniture, where not only the furnishings of the Palazzina are displayed, but also those from other Savoy residences, such as Moncalieri and Venaria. The Stables also house the gala saloon carriage made in 1805 by Parisian coachbuilder Jean-Ernest-Auguste Getting. This carriage is believed to have transported Napoleon Bonaparte all the way to Milan for his coronation as king of Italy, making an intermediate stop precisely at Stupinigi, where the emperor stayed with his wife Josephine. In 1953, psychic Gustavus Adolphus Rol bought the carriage and had it restored in Turin, helping to preserve it for future generations, and today it is back here.

In addition to the Palazzina di Caccia, which has been a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1997 as a testament to its historical and artistic significance, the Stupinigi complex includes the gardens designed by French gardener Michael Bernard beginning in 1740 and the Stupinigi Regional Nature Park. Owned by the Mauritian Order Foundation, it is still one of the most prestigious examples of 18th-century architecture in Europe, and with its wonders housed here it still continues to fascinate anyone who visits.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.