The Painter and the Scientist. The friendship between Galileo Galilei and Cigoli.

Throughout human history, the relationship between art and science has always been fruitful, complex and multifaceted with roots going back to antiquity and developing continuously throughout the centuries. The relationship between these two fields of human endeavor, seemingly so distant, shares a focus on observation and perception directed toward continuous inquiry and experimentation aimed at grasping and communicating new truths. For these reasons, the link between artists and scientists recurs constantly throughout history, with mutual contaminations: one thinks, for example, of the frequentation of Piero della Francesca and the mathematician Luca Pacioli, or that between Albrecht Dürer and the astronomer Johannes Stabius, of Leonardo da Vinci, who summed up both interests in one person (and although he is perhaps the most famous certainly not unique case), or even of the Surrealist cohort’s fascination, albeit one-sided, with Sigmund Freud. But it was between the end of the 16th century and the first decades of the following century that the fruitful collaboration between the painter Lodovico Cardi known as "il C igoli" (Cigoli, 1559 - Rome, 1613) and the scientist Galileo Galilei (Pisa, 1564 - Arcetri, 1642), so close as to delineate into an authentic friendship, which offered some of the highest achievements in their respective fields and an invaluable document for delving into the biographies and work of these important intellectuals.

Both mutually shared a passion for the two different disciplines, and while Cigoli made early use of the Galilean telescope, following up the fruit of these observations in his works as well, and willingly compared himself with hisfriend sometimes even trying to advance scientific hypotheses, Galilei on the other hand dabbled in drawing with profit, and his disciple and biographer Vincenzo Viviani wrote that the scientist used to remind his friends “that if at that age it had been in his power to elect himself a profession, he would absolutely have made election of painting.”

Despite the centuries that stand between us and these geniuses, and although some material has been dispersed, including a portrait Cigoli made of his friend, valuable evidence of this relationship is still preserved today, a rich correspondence first published independently in 1959 in the text Sunspots and Painting: correspondence L. Cigoli - G. Galilei (1609-1613) edited by Anna Matteoli, and then reissued in 2009 edited by Federico Tognoni. This is a valuable correspondence developed between 1609 and 1613, consisting of twenty-nine letters from Cigoli and only two from Galilei, as others must have been dispersed over time or perhaps destroyed by the painter’s nephew, eager to get rid of the evidence of a friendship deemed embarrassing after the astronomer’s papal condemnation. Moreover, this already fragmentary epistolary collection does not exhaust an acquaintance between the two that surely dated back several years earlier. Indeed, not only were they almost contemporaries in age-Galileo was born in 1564 while the painter was five years older-but also their places of birth were not far apart, the former being from Pisa while the latter from a small hamlet of San Miniato. For these reasons and common interests, it has been suggested that they had already met in their formative years in Florence, at the lectures of the Grand Ducal mathematician Ostilio Ricci.

Further cementing the friendship was the sharing of other passions and the same opinions on various topics, such as the boundless admiration for Michelangelo, for Dante’s music and Comedy, and for that new taste for naturalism and harmony in Florentine painting promoted by Santi di Tito, Domenico Passignano and Jacopo da Empoli.

Moreover, the two intellectuals not infrequently found themselves facing the same battles and exchanging support; Galileo’s letter sent to Cigoli in 1612 is famous, although its authenticity is questioned by some, and it was also the focus of a famous essay by Erwin Panofsky, published in Italy as Galileo critic of the arts. In this missive, the scientist expounds on the discussion of the comparison of the arts, inaugurated in the modern era by Leonardo da Vinci, perhaps to help his friend in a challenge that the painter must have faced on the building site of the papal basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore where he found himself working at the same time as sculptors, including Pietro Bernini, while he was creating a fresco of the Pauline dome.

In his remarks, Galilei resolutely endorses the superiority of painting over sculpture, thanks to the “very natural colors of which sculpture lacks,” which is instead endowed by nature with light and dark, which, however, painting also achieves through art and for this reason to be preferred since “the more the means by which one imitates are distant from the things to be imitated, the more wonderful the imitation is”; moreover, also rejecting the argument of the eternity of sculpture that “is worth nothing, for it is not sculpture that makes marbles eternal, but marbles make sculptures eternal, but this privilege is no more his, than of a rough stone.”

No less did Cigoli also do the opposite, always offering his moral support to the scientist often opposed in his theories by critics and opponents: “Write the truth without passion et without caring to flatter or cede the field to fortune, nor for them delay the course, if well there is pippioni like geese. Laugh it off, Sig.r Galileo [...],” he wrote in a 1613 letter, while in others he contemptuously apprises his opponents as “can botoli,” “uccellacci,” and “satrapi romaneschi,” recalling how one of them “resembled Pilate [...] and that if I had to paint ignorance, I would portray none other than him.” And when Galileo gave birth to the publication Discorso intorno alle cose che stanno in su l’acqua, Cigoli compared Galilei’s discoveries with the works of Buonarroti: “Et mi credo che avvengha lo istesso lo istesso come quando Michelagniolo cominciò ad architettare fuori dell’ordine degli altri fino ai suoi tempi, dove tutti unitamente [...] dicevano che Michelagniolo aveva rovinato la architettura con tante licenze fuori di Vitruvio” and urged him, “Però non si sbigottarsi; seguiti allegramente.”

Traces of the friendship between the two also remain in their respective works, which were influenced by each other; in particular, it is the painter who partly renewed his iconography in a number of important works, for example, inserting the lunar body in theAdoration of the Shepherds of 1599, now housed in the Metropolitan Museum in New York, and in the canvas with the same subject painted three years later for the church of San Francesco in Pisa. In the Deposition at the Galleria Palatina in Florence, painted between 1600 and 1608, Cigoli paints the sun and moon at the ends of the Cross, probably stimulated by the debate about celestial bodies, in which Galilei had a preponderant role.

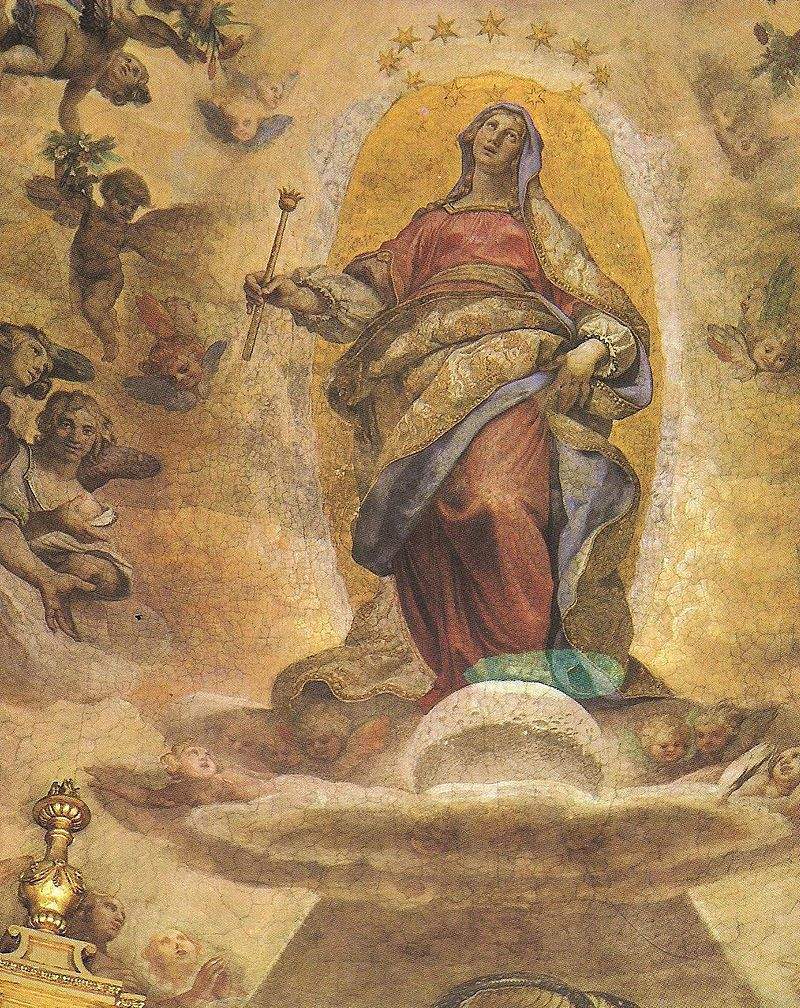

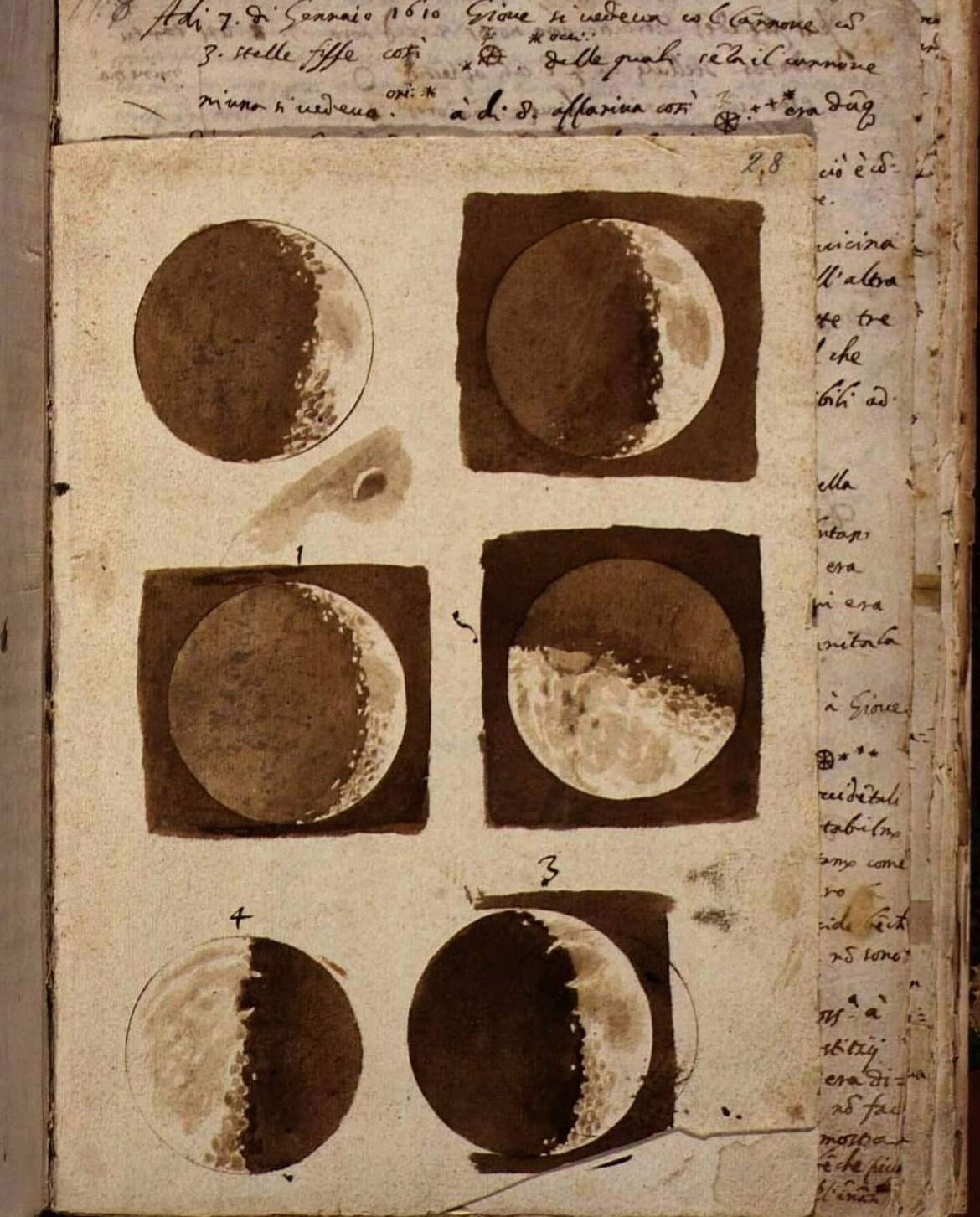

Even more blatant and notorious is the contribution of Galilean theories on one of the most important commissions obtained by Lodovico Cigoli namely the aforementioned realization of the fresco for the dome of the extraordinary chapel that Pope Paul V was having built in Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. The commission he obtained in 1610 and completed two years later is known today as the depiction of theImmaculate Conception, among Apostles and Saints, although there are some controversies about the iconography. Cigoli had to endure considerable labors for the realization, which are amply described in the missives between the two: “Io attendo a salire 150 scalini a Santa Maria Maggiore et a tirare a fine alleggramente, a questi caldi estivi che disfanno altrui; et ivi, senza esalare vento né punto di motivo di aria, tra il caldo e l’umido che contende, me la passerò tutta questa state.” However, on those scaffolds Cigoli also had the opportunity to experiment with the Galilean telescope, drawing for his friend the Observations of the Lunar Phases, in which he transcribes the lunar cycle in twenty-six phases.

Moreover, on the basis of the plates contained in Sidereus Nuncius, a treatise published by Galileo precisely in 1610 and containing many of his discoveries, including one on the surface of the moon, certainly not as polite and pristine as imagined in the past, but riddled with craters and a jagged morphology, Cigoli therefore decided to make a “Galilean” moon in the Roman work. In fact, their mutual friend, Federico Cesi, founder of the Accademia dei Lincei, commented on Cigoli’s work, “S’è portato divinamente nella cupola della cappella di S. S.ta in S. Maria Maggiore, and as a good and loyal friend he has, under the image of the Blessed Virgin, pinto the Moon in the manner that was discovered by V.S., with the crenellated division and its islets.”

In fact, Cigoli gave immediate reception to Galilei’s research and included in his work a living treatise on science. And Galileo also availed himself of his good friend, when together with Cesi he was preparing the treatise Istoria e dimostrazioni intorno alle macchie solari published by the Lincei, not only making use of those twenty-six celestial observations taken from the scaffolding of the dome, but also when endorsed by the artist’s consent, they called upon the Strasburg engraver Matthias Greüter to produce the iconographic apparatus of the volume. Moreover, in all likelihood Cigoli, had also provided the drawing of the portrait of Galilei in doctoral robes made for the treatise’s antiporta.

Unfortunately, barely a year after the work was completed in the papal basilica, Cigoli was struck down by illness in 1613, and little use was made of the help even of prestigious figures such as Cardinal Maffeo Barberini, who sent his personal physician, Giulio Mancini, also known for having written the essay Considerazioni sulla pittura. In fact, in June of that year Lodovico Cardi passed away. And although no direct evidence is preserved of the grief and emotion that must certainly have struck Galilei upon discovering the death of his friend, from some letters of correspondents with the scientist we can get a partial idea, such as that of Federico Cesi: “And for V.S. and for me, being a mutual and true and good friend, I have felt that greater sorrow that can be said of the loss of Sig. Cigoli, nor do I know anyone to whom it is not sorrowful, so well known was his kindness, goodness and excellence, et so seldom are these qualities to be found conjoined, nor will I fail and for his merits and servitii and at the nod of V.S., exhibit myself ready for the benefits and servitii of his house and grandchildren”; while Luca Valerio spoke of “the acerbissimo dolore della nostra comune perdita del soavissimo amico S.r Cigoli, anzi comune perdita del secol nostro.”

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.