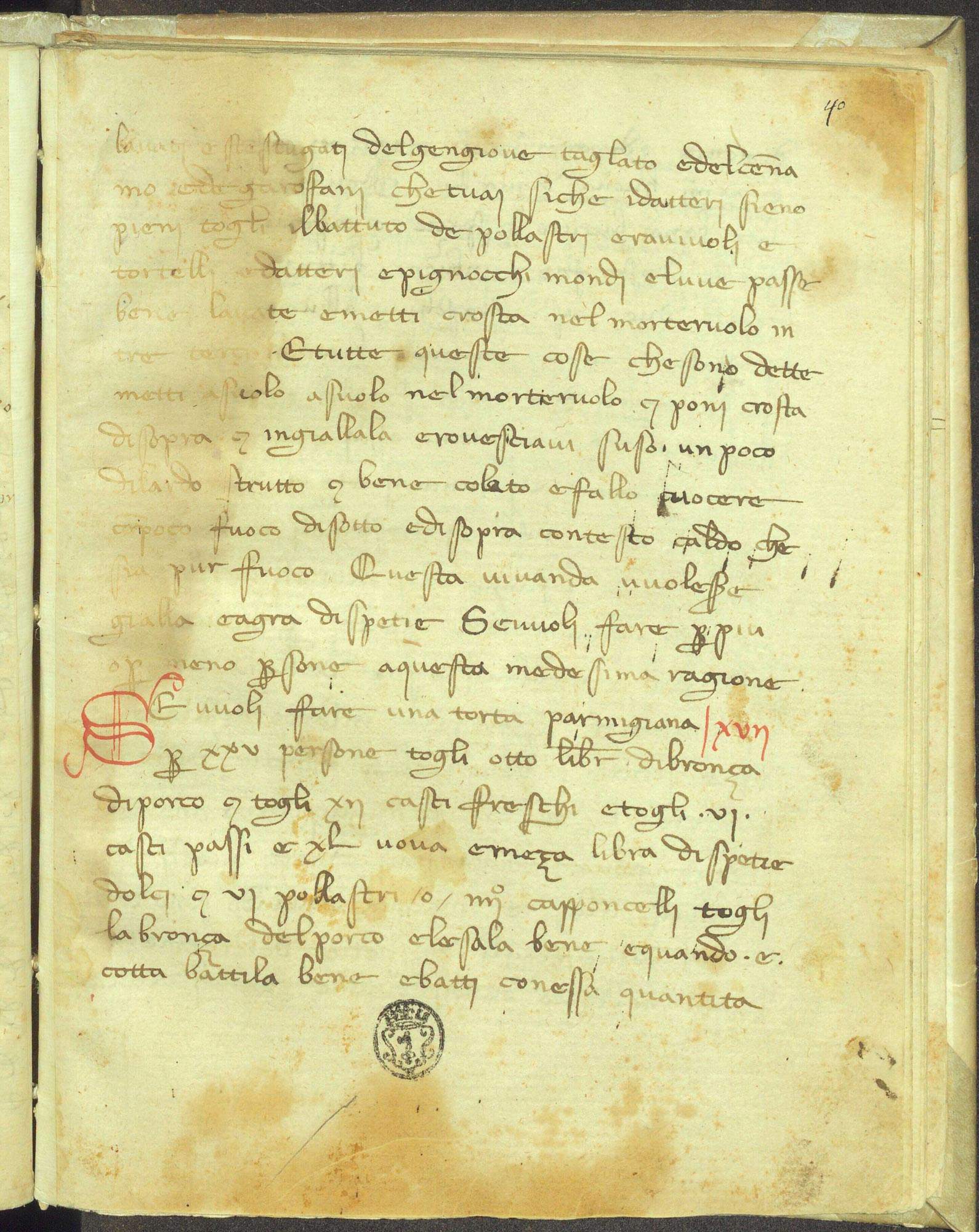

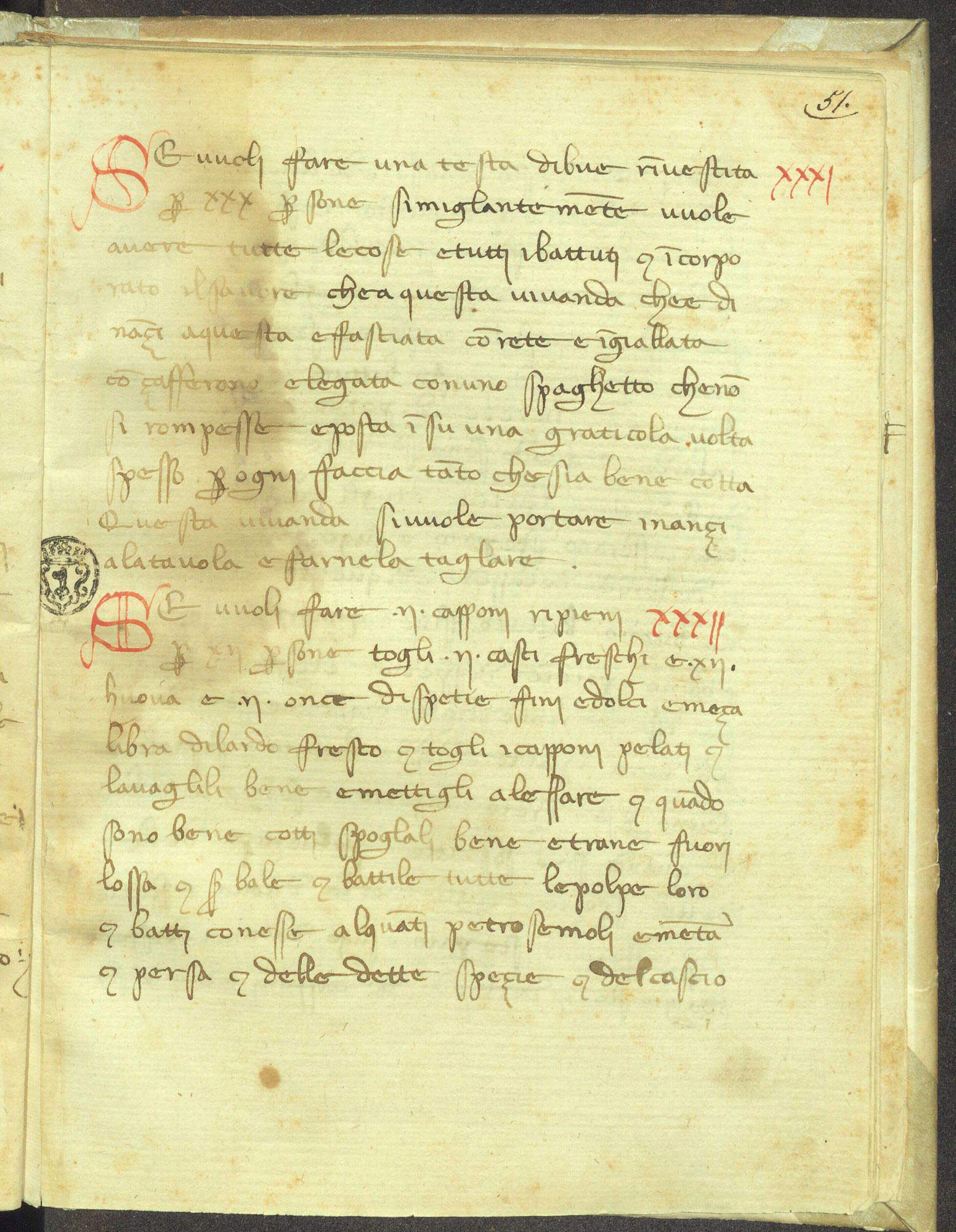

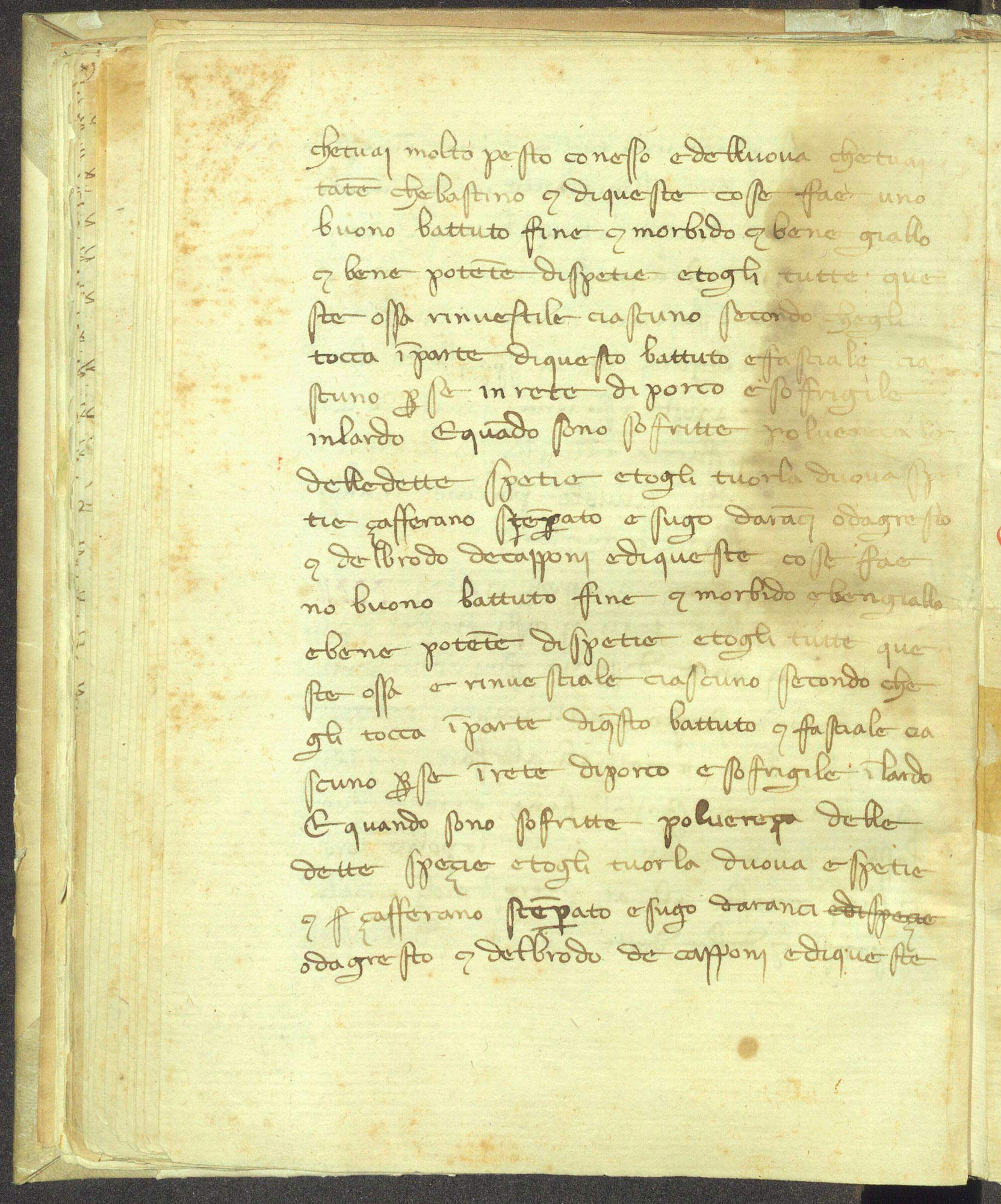

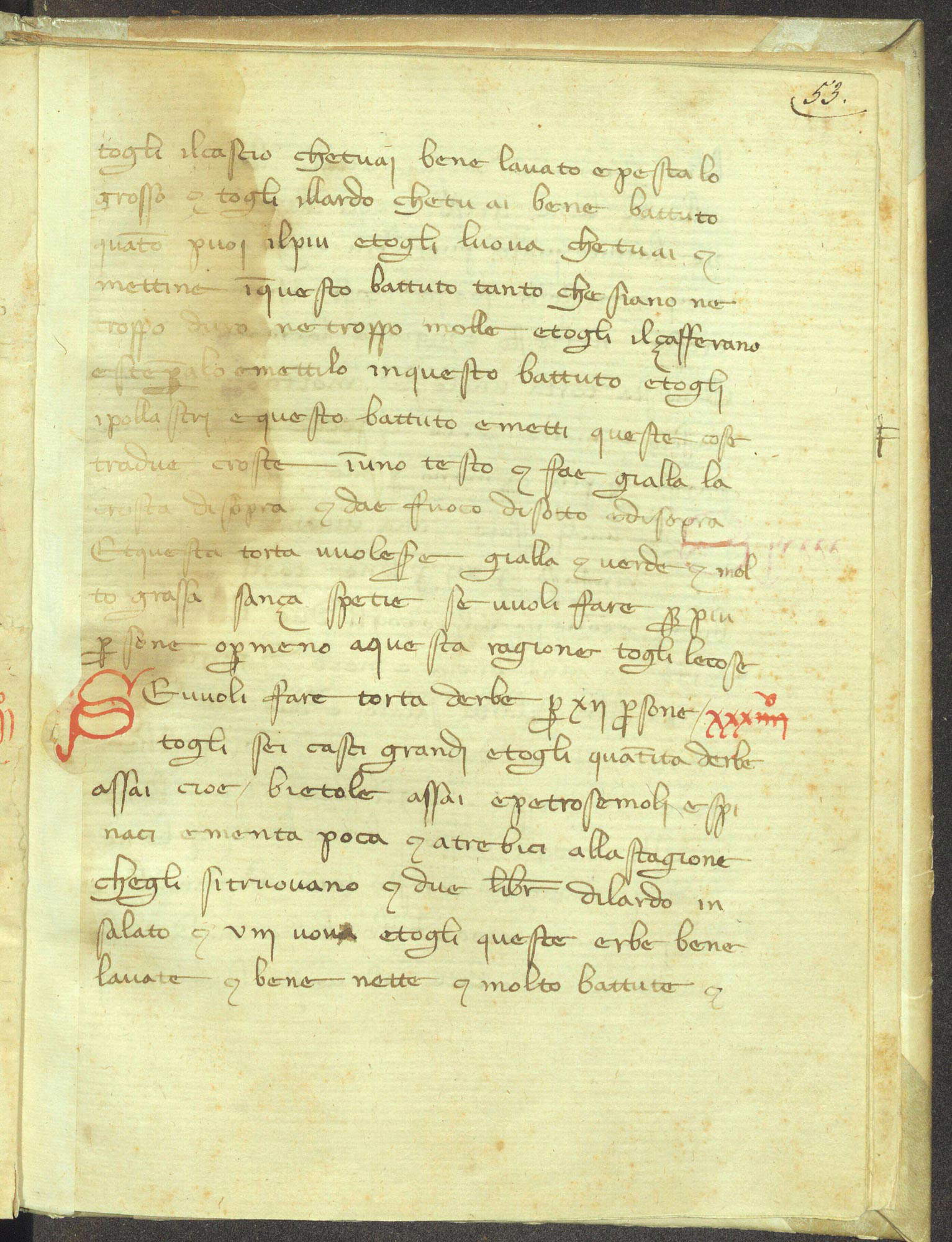

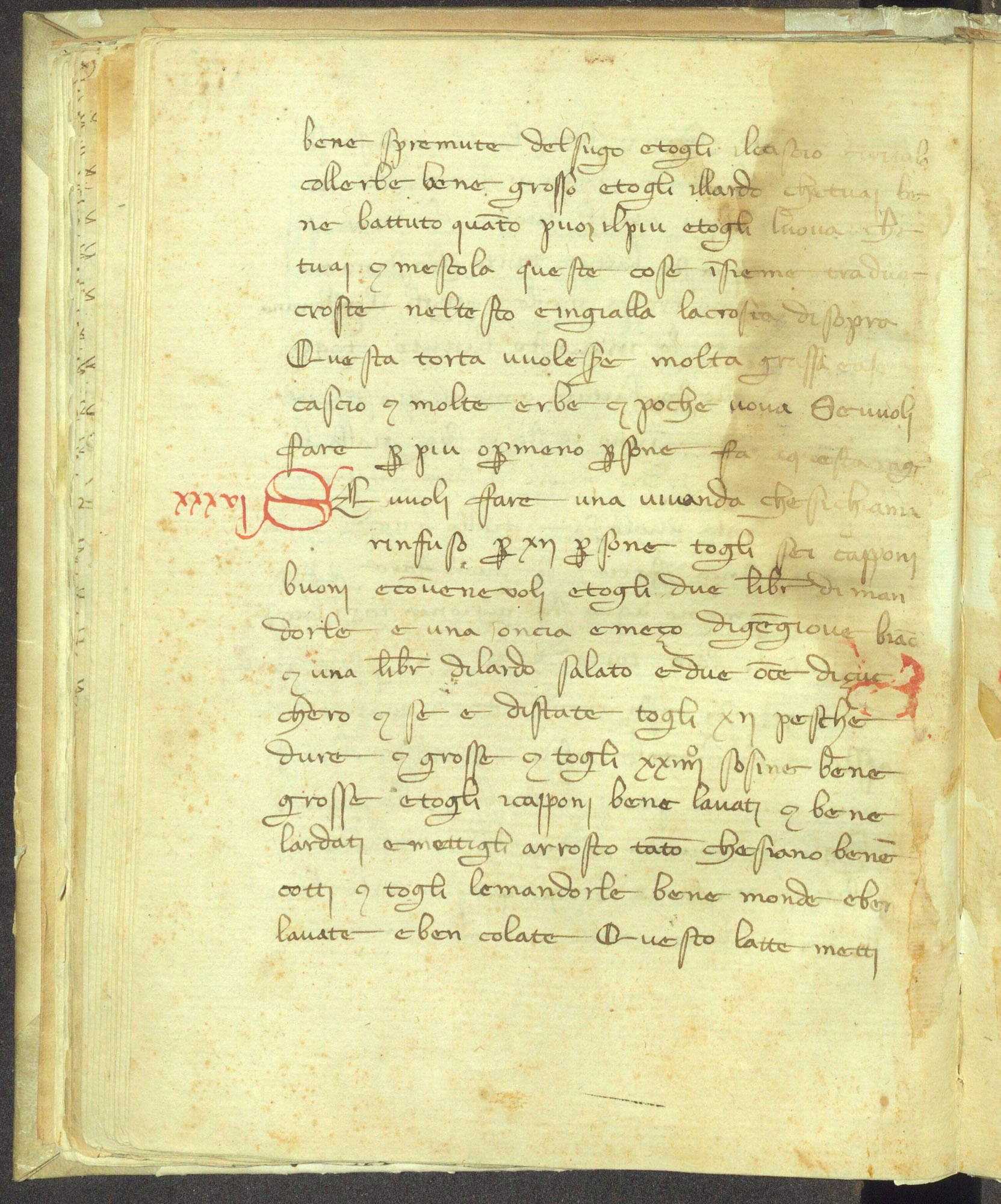

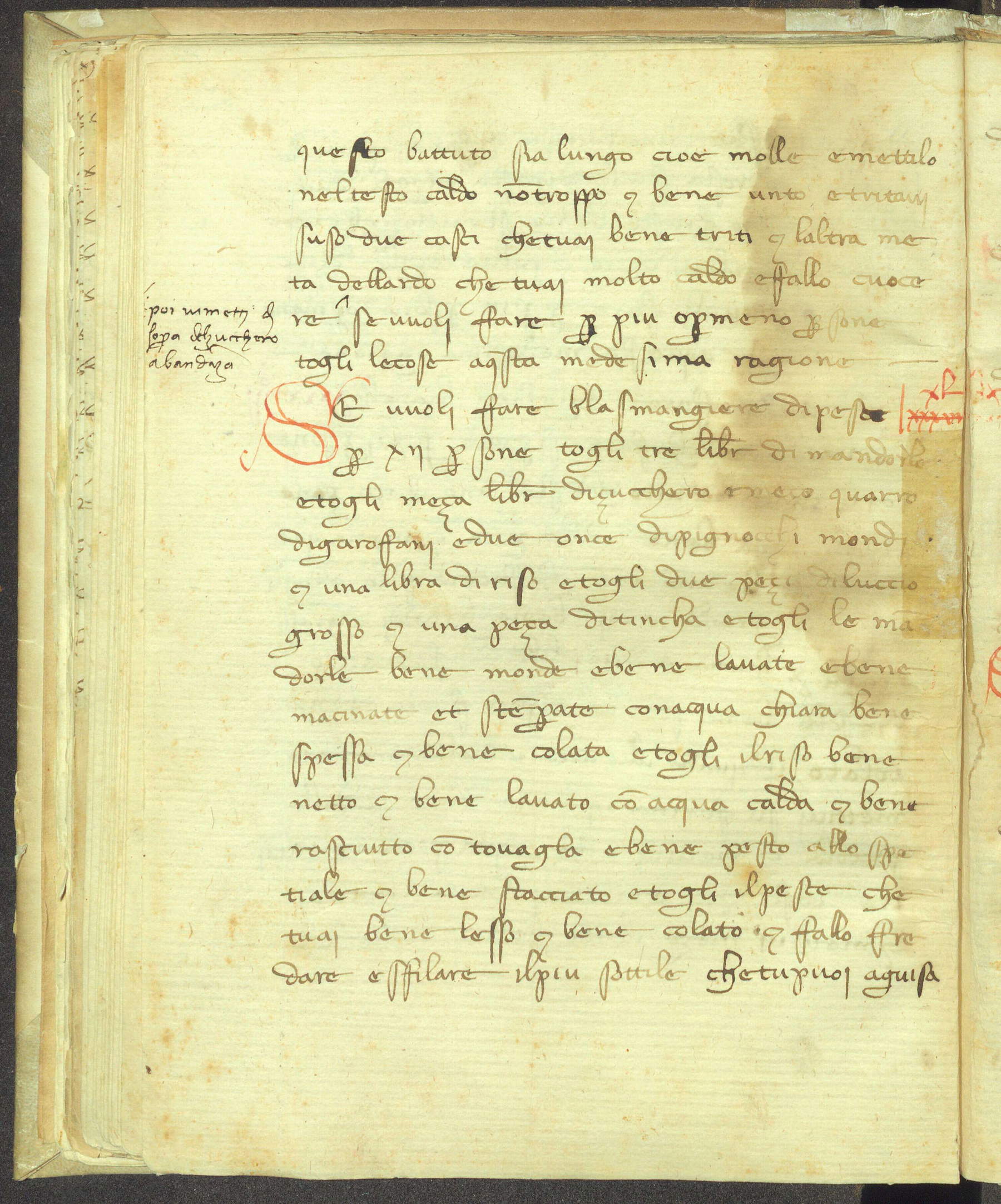

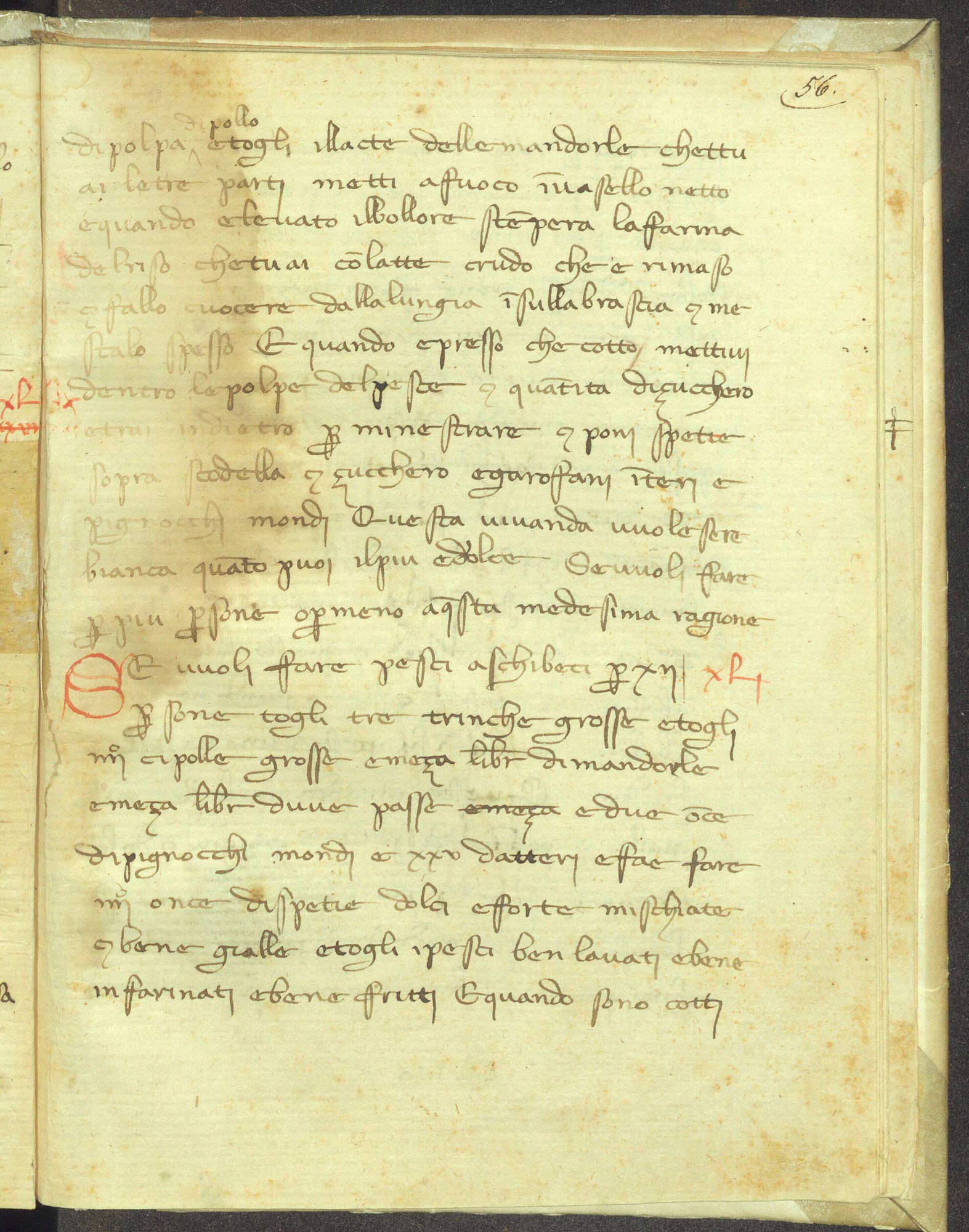

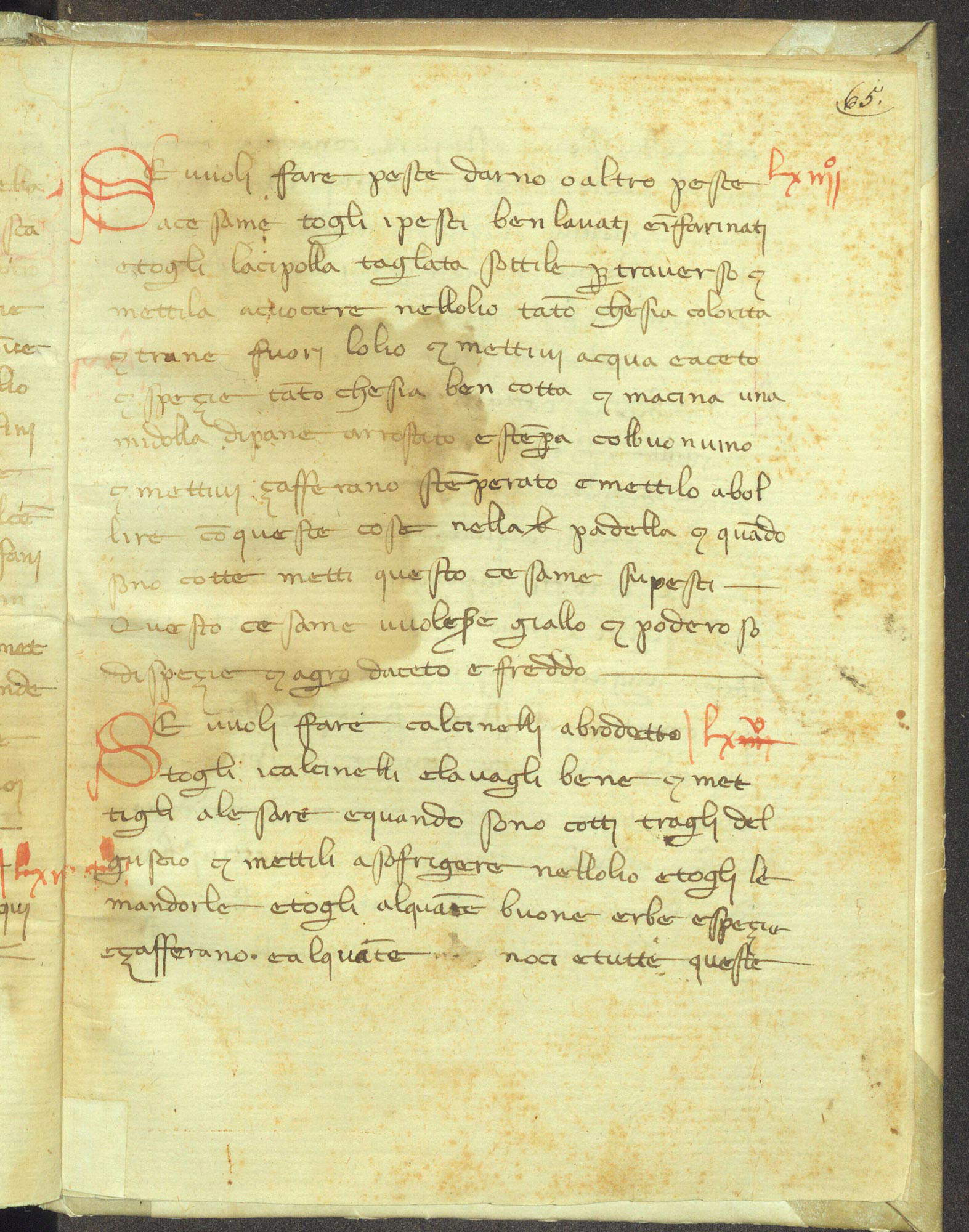

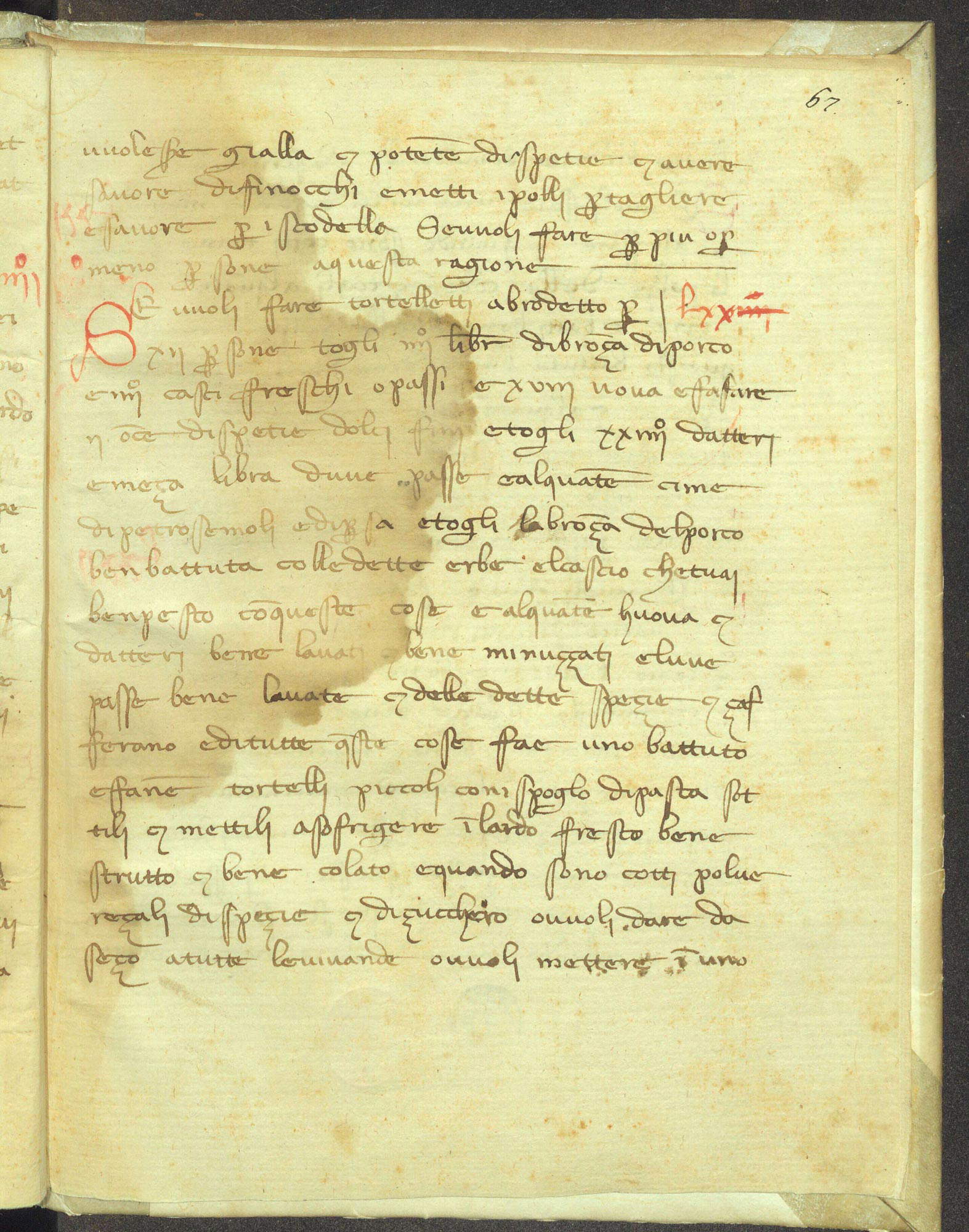

Fifty-seven handwritten recipes in a codex from the 1420s: it is the Modo di cucinare et fare buone vivande and according to our knowledge is the oldest cookbook in the Florentine vernacular. The cookbook is in a composite codex kept at the Biblioteca Riccardiana in Florence, number 1071, consisting of three sections (the first is a Commedia delle ninfe fiorentine by Boccaccio copied in the 15th century, the second contains a set of rules of computation, and finally the third, from folio 40 to folio 67, is devoted to recipes). The book is of great importance because, after Apicius’sDe Re Coquinaria, which moreover was no longer copied from the 9th century onward, no other cookbooks are recorded, at least based on our knowledge: the cookbook genre will appear again between the 13th and 14th centuries. In the early Middle Ages, cooking was in fact transmitted mainly by oral tradition, and the profession of the cook proper (a person who by trade cooks for others) was not recognized until the late 14th century: it was probably the codification of the cook’s trade that was one of the main reasons that led to the spread of cookbooks, which thus became useful professional tools.

In any case, we do not know who the author of this cookbook was, but scholars consider it the progenitor of a set of fourteenth-century cookbooks known as "of the Twelve Gourmets,“ due to the fact that the recipes were designed for dinners in which twelve diners would participate. Diners whom, moreover, nineteenth-century scholars who studied the codex thought to juxtapose with the ”brigade in che disperserse Caccia d’Ascian la vigna e la gran fonda e l’Abbagliato suo senno proferse" mentioned by Dante Alighieri in Canto XXIX of theInferno, that is, the legendary “spendthrift brigade,” a group of twelve young Sienese friends known for being great squanderers and squandering vast fortunes in gozzoviglie, whose story nevertheless has the contours of myth. What seems fairly certain is that the environment for which this cookbook was intended was that of theurban upper middle class, and in particular to the newly rich of the time who liked to spend a lot to eat the most refined and elaborate foods.

Anonymous, Recipe of Parmesan

Anonymous, Recipe of Parmesan Anonymous

Anonymous Anonymous, Recipe

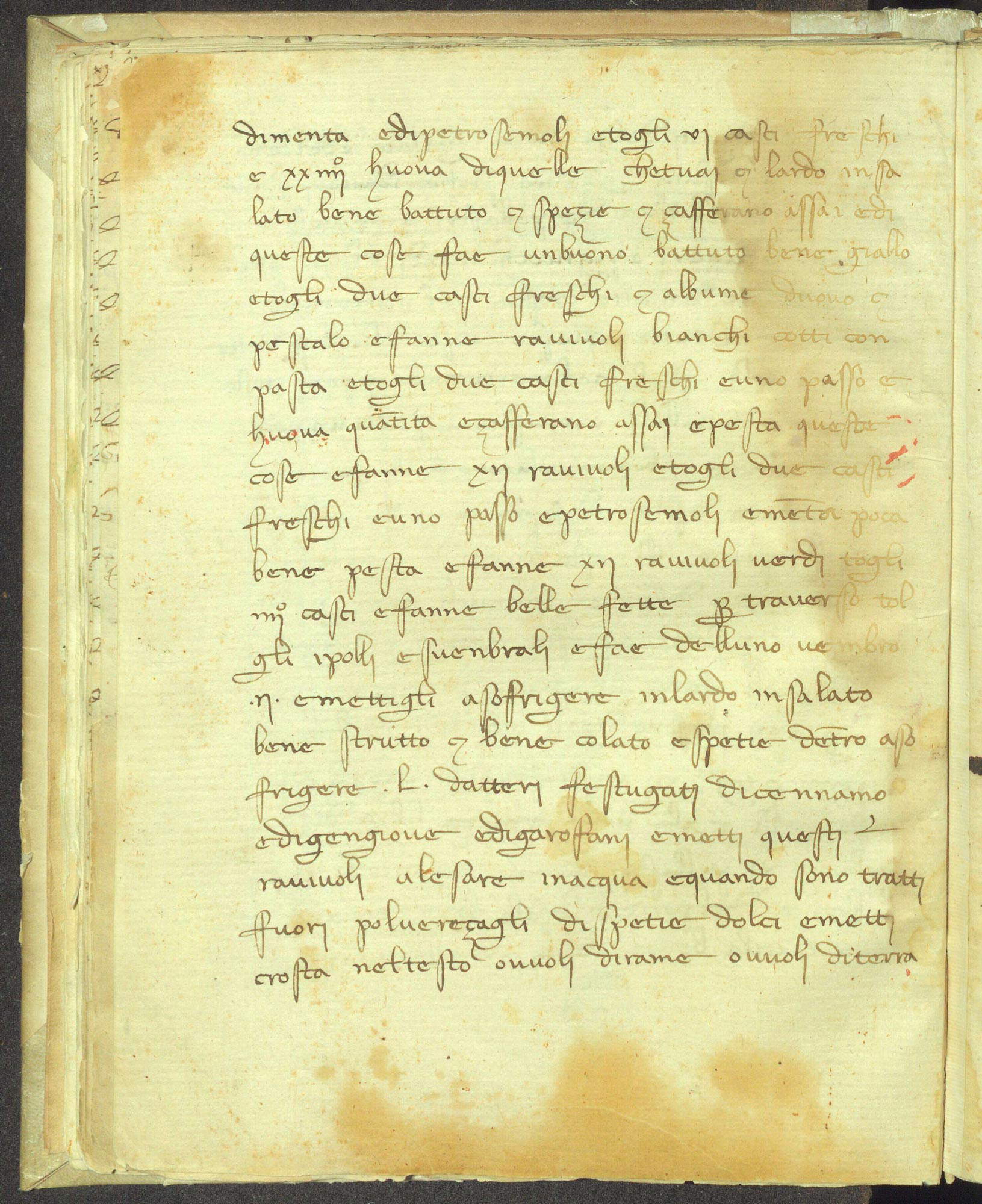

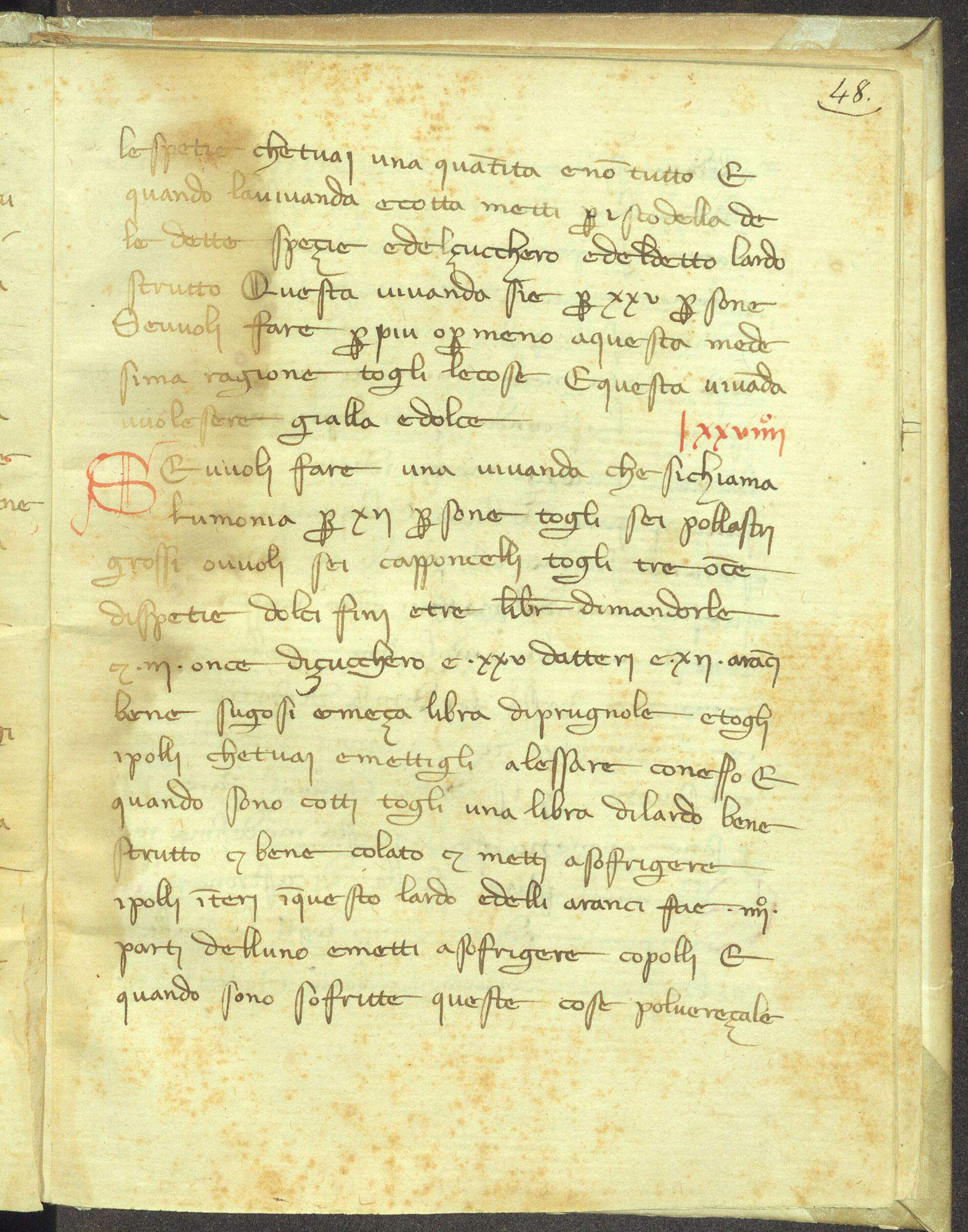

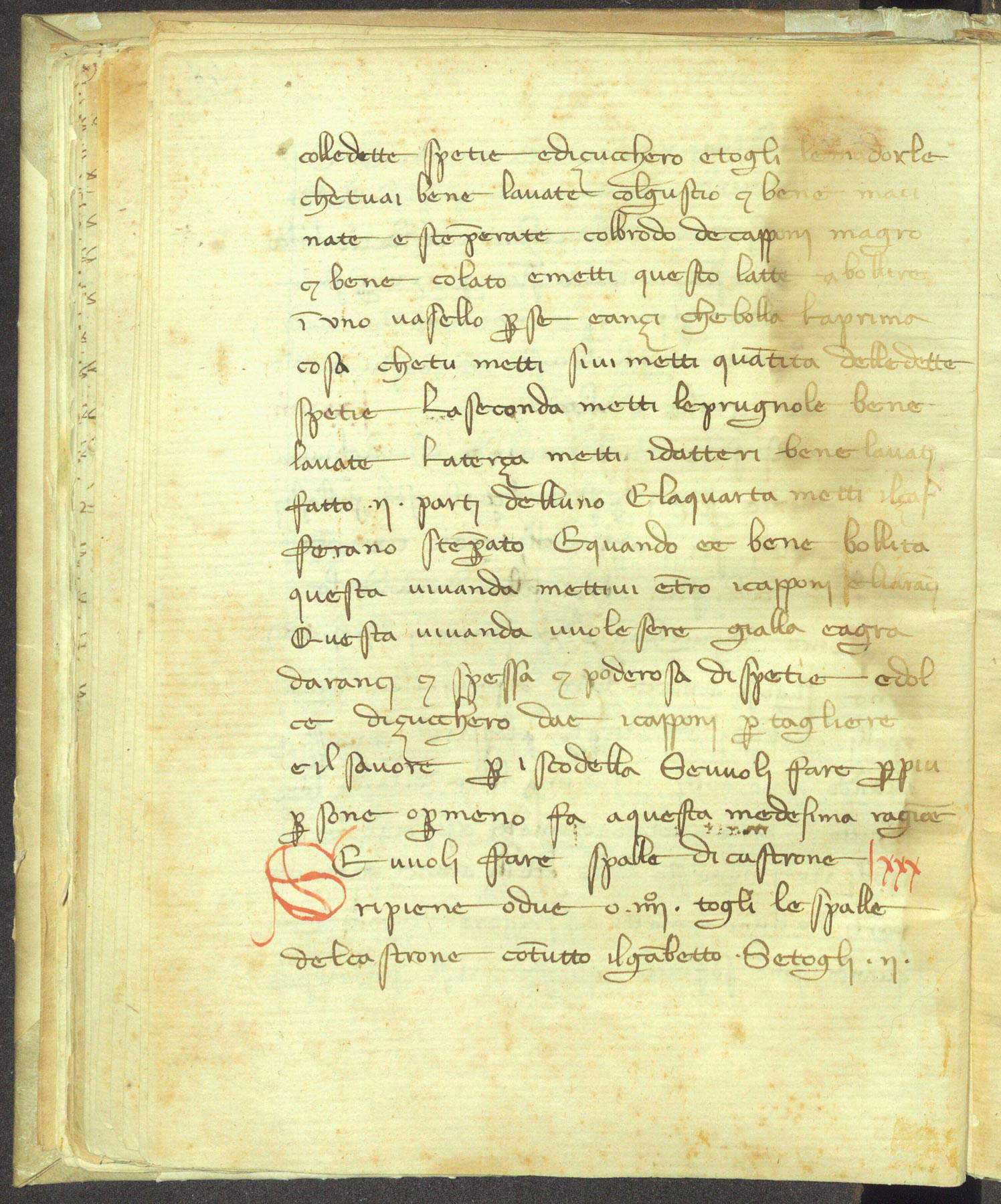

Anonymous, RecipeThe preparations proposed by the cookbook are “rich,” explains scholar Simone Pregnolato (editor of the first critical edition of the cookbook in Riccardiana manuscript 1071), "opulent even, and exhibit abundant doses and expensive ingredients, of typically bourgeois prerogative (such as lard, various cuts of pork such as arista and ’ castrated lamb,’ or such as spices, used in an almost exaggerated manner): which raises the suspicion that it was precisely to this class of the newly rich that the cookbook might have been addressed and intended." The book is written entirely in Florentine vernacular, but the most interesting aspect from a linguistic point of view, according to Pregnolato, lies in the organization of the period and the lexicon used by the author. In fact, the sentences are all in the second person singular, the periods are simple and paratactic, and the sentences are always constructed in the same way (they begin with an “If you want to make” followed by the name of the recipe, and the list of instructions): it follows that this cookbook was intended for practical use. Even the handwriting indicates to us that this is not a particularly elegant manuscript: the copyist, explained scholar Irene Ceccherini, “employs a notarially based cursive tradition writing. Although showing good graphic competence, judging from the alignment, the respect for form and proportion and the regularity with which the graphic signs are traced, the writing is not formalized on the level of style and is characterized by a ’spontaneous’ cursive style: in other words, in transferring his own writing to the book with literary content, the copyist did not change either the structure of the letters or the expressive properties of his usual documentary graphic base.” Notarial writing, in essence, thus writing with a marked practical character.

In terms of vocabulary, there are two aspects that are likely to surprise those approaching medieval cookbooks for the first time. The first aspect is the high number of terms that are still used today, seven hundred years after the manuscript was written, to indicate the same preparations (e.g., “fegatello,” “frittelle,” “mandorlata,” “migliaccio,” “porrata,” “ravioli,” “tortelletti,” “tortelli,” and “vermicelli”). Other names, however, indicated different dishes: while today by “tart” we mean a cake usually filled with jam, marmalade or hazelnut cream, at that time it was a savory pie, just as “tartar” was not the preparation of finely cut raw meat, but a pie made of cheese, eggs and sugar. The second aspect, on the other hand, is the large number of terms borrowed from the French language, such as “butter,” “brodetto,” “pevere” (pepper), and “blasmangiare” (blancmange, a dessert made from rice, fish, milk, almonds, and various spices). The language of cooking in the 14th century was thus already characterized by a great variety of terms, regional names (e.g., “calcinelli,” or clams), and a high number of forestierisms.

What are some of the specialties that the book suggests to its readers? The book, as it has reached us (in fact, the first part is missing), opens with a recipe for “torta parmigiana” (with doses for as many as twenty-five people): bacon, cheese, eggs, and chicken or caponcelli are taken, after which some ravioli are stuffed with the cheeses while the chickens are to be cleaned and cooked in lard and seasoned with cinnamon dates and spices, and once cooked the ravioli are to be placed together with the chicken inside a sheet of pastry placed over a testo, and then proceeded with the cooking. Another similar recipe is that of “torta frescha” for twelve people: six chickens and half a pound of grapes are taken, the chickens are sautéed in lard and seasoned with spices, after which once cooked they will be inserted into the pastry along with the grapes and the whole thing will be cooked. “Fish blasmangiare,” on the other hand, is made with almonds, sugar, cloves, pine nuts, rice, pike and tench. You have the almonds dissolved in milk and the rice boiled, after which you boil the fish, let it cool and have it “drawn out as thinly as you can, in the guise of chicken flesh,” then combine it all by cooking it in milk until you get a vivanda that “wants to be as white as you can as much as you can, and sweet.” And speaking of fish, there are several recipes for cooking lamprey: crusted, roasted, “a cialdello amorsellata” (that is, in a soup where the lamprey is cut into small pieces: a kind of fish goulash).

Anonymous, Recipe of stuffed

Anonymous, Recipe of stuffed Anonymous, Recipe of

Anonymous, Recipe of

A feature that recurs often in these recipes are the sweet and sour flavors, such as those of lumonia, a recipe for chicken, boiled with sugar, dates and oranges and then later sautéed in lard, and finally sprinkled with spices and sugar, and further mashed in milk and almonds (the author himself writes that “this vivanda is meant to be yellow and sour of oranges [and] thick [and] mighty of spetie and sweet of çucchero”). Then there are recipes similar to specialties we still eat today, such as "torta d’erbe, " similar to erbazzone reggiano: for twelve people, you take “sei casci grandi” (six large cheeses), chard, parsley, spinach, mint, “atrebici” (red chard), make a mixture of the herbs and mix it with eight eggs and then later combine it with the shredded cheese, and the mixture will be placed in a “crust,” that is, in a pastry, which will then be baked. There is no shortage of “tortelletti d’ella” (i.e., filled with enula campana) cooked in capon broth (there is also a sweet version of tortellini in broth, by the way), or even stuffed capons. Much more distant from our customs, however, are the “tria di vermicelli” (vermicelli soup), a dessert made with almonds, milk, sugar and, precisely, vermicelli, or the eel or chub tart, or the “fish a cesame,” that is, seasoned with a sauce made with onion, breadcrumbs, wine and saffron.

One can therefore easily see the sumptuousness of these recipes just by scrolling through the ingredients: the spices, which were particularly expensive, were mostly inaccessible to the lower strata of the population, and even lard was the condiment used in rich recipes instead of oil, which was considered much less valuable. It was therefore not a cuisine for the poor, that of the Way of Cooking and Making Good Food.

Finally, a further interesting aspect of the Riccardiana Library cookbook is its role in the debate about its status as a sectional language for cooking jargon, an issue that still concerns it today. In short, is it possible to place culinary language among the technical-scientific ones? Scholar Giovanna Frosini listed some elements against this hypothesis, such as the lack of unambiguousness of correspondence between objects and their names, the lack of a unified and coherent terminology, the use of language that is not always controlled, and conversely, the use of terms that are often improper and forced (just think of cooking programs on television). In other words, “the language of cooking has, yes, a specialized terminological background, but it interacts - and powerfully - with the common language.” On the other hand, the exclusively culinary uses of some terms that originated in other contexts (some examples: arista, mostarda, vermicelli), and some recurring elements such as suffixes in “-ata” (tart, mandorlata, porrata), expressions such as “x-style dish,” neologisms should be included among the points in favor. Within this discussion, Modo di cucinare et fare buone vivande is useful for highlighting how since the Middle Ages there are elements in the language of cooking to comfort the idea of its technical status: for example, Pregnolato lists, “the extraordinary variety of names, the great abundance of geosynonyms, the spread abroad, the progressive enrichment of the vocabulary thanks to dialectalisms, the large number of forestierisms, the presence of cases of remarkable continuity between the past and the present.”

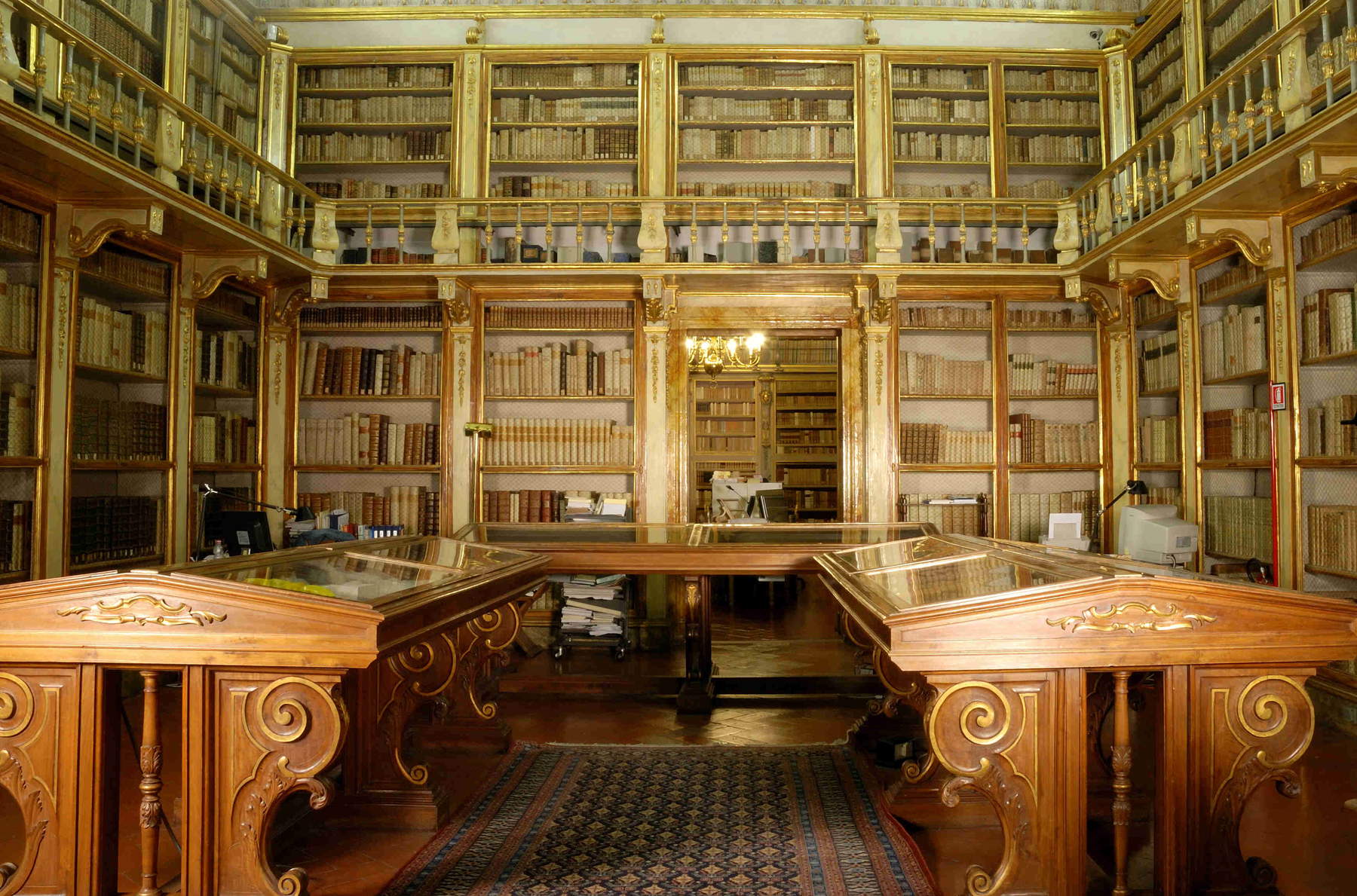

The Biblioteca Riccardiana of Florence, located in the Medici Riccardi Palace, originated in the late sixteenth century with the action of the Florentine nobleman Riccardo Romolo Riccardi, who began acquiring the books that would later form the main nucleus of the collection. In 1659, the Riccardi purchased the Medici palace on Via Larga, i.e., the library’s current home, and began to renovate it and place the books in the collection here. The ballroom, with its celebrated frescoes by Luca Giordano, became the vestibule of the Library Room, which had meanwhile grown with the acquisitions of Francesco Riccardi, who personally oversaw the arrangement to be given to the library. The Library was in danger of being dispersed in the early nineteenth century, when the family, due to financial instability, put it up for auction: however, it was purchased by the City of Florence in 1813 and given to the State two years later. From that moment, therefore, the Riccardiana became a public library, even though it was already accessible to the public at the time of the Riccardi (in fact, since 1737 men of culture were given the opportunity to consult the books).

Today the Riccardiana has a patrimony consisting of 4,450 manuscripts, including autographs by Petrarch, Boccaccio, Savonarola and the greatest humanists (Alberti, Ficino, Poliziano, Pico della Mirandola), valuable illuminated manuscripts, 5,529 loose papers, 63,833 printed books (including 725 incunabula and 3,865 cinquecentine), and 276 drawings belonging to the Riccardi collection.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.