The mystery of the Madonna and Child by Bartolomeo Caporali, a piece of Mantegna culture in Umbria

When the wave of demanations that followed the Unification of Italy brought to the museums of Umbria a huge amount of works arriving en masse from the churches and convents of the territory, it is likely that animated discussions immediately arose among art historians in Perugia around a panel that arrived from the sacristy of the church of Sant’Agostino: in the 1860s it had been removed from the place where it was kept, and would later reach what was then the Pinacoteca Civica of Perugia, now the National Gallery of Umbria. It is here that the painting can still be admired, and moreover with the new arrangements inaugurated in July 2022 the uniqueness of this work has been well highlighted.

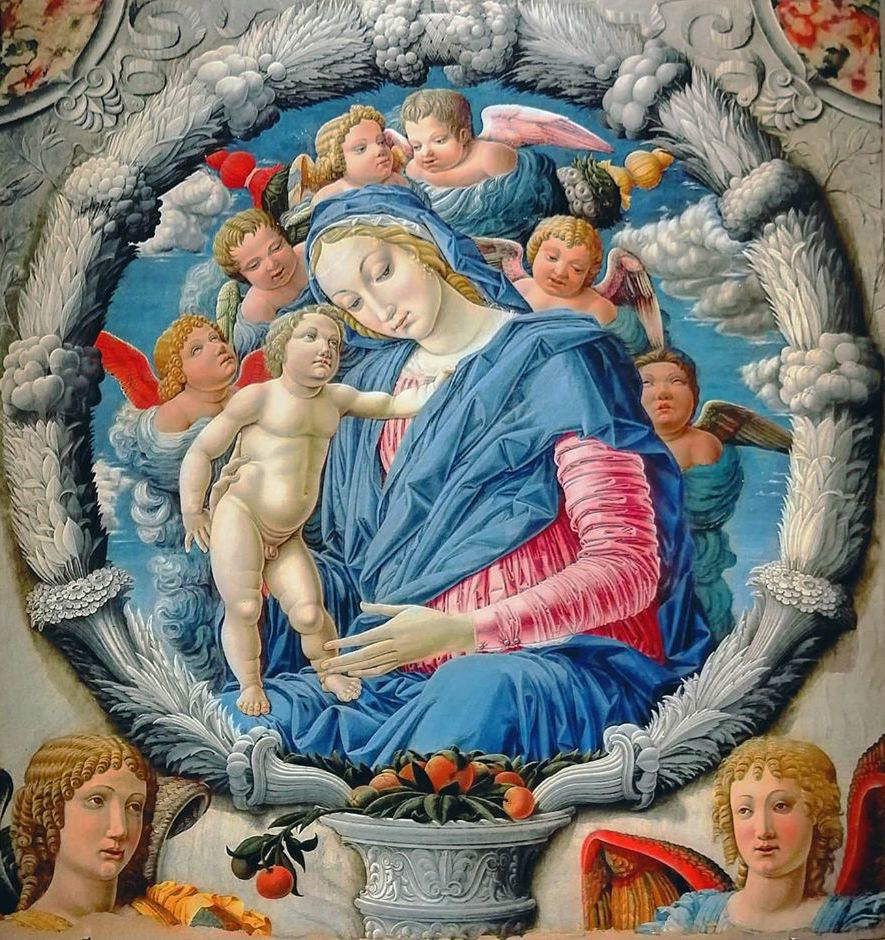

A delicate Virgin with long arched eyebrows holds on her knees a Herculean Child, who stands and holds with one hand his mother’s cloak, an intense lapis lazuli blue. Arranged around them are the figures of six cherubs, three on each side: singular is the invention of the author, who has clothed their bodies in sea-green tunics, which blend in with the blue of the sky and look almost like clouds moving in the wind. The figures are framed within an imposing marble garland decorated with festoons of fruit and flowers, painted with strong chiaroscuro effects to provide the viewer with the illusion of three-dimensionality: look at the long, somber shadow that, on the right, the festoons cast on the faux-marble background. The pretense is completed, on the sides, by two medallions that inside simulate breccia inserts in yellow and orange tones, and at the bottom by a pedestal on which the painter has arranged some orange trees with their leaves, which fulfill the same role as the apple and thus become a symbol of redemption of sins and salvation. On the sides, in the corners, appear two blond angels, whose heads and shoulders we see only, and in whom we must probably recognize the archangels Gabriel and Michael. On the left, an orange sprig sticks out to offer a further essay in illusionistic virtuosity.

It is clear that we are dealing with an artist who must have known, and well too, the art of Andrea Mantegna: the opening to the blue sky recalls the oculus of the Bridal Chamber, the almost metallic folds marking the sleeve of the Virgin’s robe also recall similar Mantegna solutions, and the same can be said for the sculptural outline of all the figures, as well as the exactness of the faux marbles. The shape of the garland itself is identical to that of the frames of the Caesars in the Bridal Chamber.

The proximity of this painting to Mantegna is such that, in the guide to the National Gallery of Umbria compiled by Giovanni Cecchini in 1932, the painting was classified as being of the 15th-century “Paduan school.” And almost all the scholars who had grappled with this work had approached it to artists from the northern area: for Richard Hamann it was a work by Francesco Bonsignori, for Giacomo De Nicola and Mario Salmi it should instead be assigned to the hand of Gerolamo da Cremona (a name, the latter, also supported between the 1950s and 1960s by Roberto Longhi and Rodolfo Pallucchini). However, as early as 1863, that is, when the Commission in charge of the demanization of works of art for the province of Perugia compiled the inventory of objects from the houses of suppressed religious orders, the name of an Umbrian artist, Fiorenzo di Lorenzo, began to circulate: this was the possible arista indicated by one of the members of the commission, Luigi Carattoli, and this was the name that until the early twentieth century continued to be assigned to the author of the painting, only to come back into vogue in the postwar period (the opinion of Federico Zeri, another supporter of Fiorenzo’s name, probably had some relevance), and finally reaffirmed by Filippo Todini in 1989.

This panel, in short, has always been a mysterious object for anyone who has studied it. Only in 1994 was the enigma probably dissolved: a major revision of the catalogs of Umbrian painters of the fifteenth century had begun at that time, and that year Pietro Scarpellini advanced, albeit very cautiously, the name of Bartolomeo Caporali, destined to supplant that of Fiorenzo di Lorenzo thanks in part to the later confirmation of Elvio Lunghi, according to whom the Madonna and Child within a Garland would be inexplicable without a stay in Mantua by the artist, or at any rate without his approximation to the manner of Niccolò di Liberatore, known as the Pupil, who had actually been in Padua. Caporali was one of the greatest Perugian painters of the fifteenth century: already enrolled in the Arte dei pittori in 1442, he had begun to establish himself at a very young age by looking to the achievements of Benozzo Gozzoli, who was in Umbria in the 1450s, Beato Angelico but also his countryman and contemporary Benedetto Bonfigli, the other great name in painting in Perugia in the mid-fifteenth century.

This singular panel has been assigned to him on stylistic grounds: the profile of the Madonna, but also the same manner of draping the garments, are almost superimposable to those of the Virgin who appears in theAdoration of the Magi painted for the Convent of the Poor Clares of Monteluce and now also preserved at the National Gallery of Umbria. A mature work, then, if to be juxtaposed with that painting: it could date from the 1570s. And an anomalous work, as has already been said: there is no work in the whole of Umbria so adherent to the modes of Mantegna, which are, however, diluted by the artist with a Virgin with a sweet, delicate, graceful profile even in the sculptural evidence that the artist decides to give to her flesh. It is a strange encounter between two schools, it is an unusual fusion of northern and central Italy, at a time when it was certainly not unusual for a painter to move even far from home to study the novelties that were spreading outside his regional sphere. We do not know for certain about trips to Mantua by Bartolomeo Caporali. It may well have been enough for him to see the illuminated codices of Gerolamo da Cremona that he might have observed in the city: the Cremonese man was a profound observer of Mantuan art, and his codices abound with sculptural figures framed by rich garlands. However, the idea that Bartolomeo Caporali traveled a long way to reach the city of the Gonzagas, and that here he met that Paduan younger than himself by eleven years, who may have inspired him, with his brand-new solutions, totally unknown in his native Perugia, this panel that still represents a kind of hapax in Umbrian fifteenth-century painting.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.