The music that accompanied the horror of Mauthausen and the photographer who saved it

Dance me to your beauty with a burning violin

Dance me through the panic till I’m gathered safely in

Lift me like an olive branch, be my homeward where

And dance me to the end of love.

(Leonard Cohen)

Dance me to the end of love by Leonard Cohen (Montéreal, 1934 - Los Angeles, 2016) is one of the rare songs to which any attempt at translation would take away rather than add. Thus, those who do not speak English must content themselves with knowing it through commentary and paraphrasing. It is a song of no easy interpretation-a characteristic common to almost all Leonard Cohen songs. And it is, according to a recurring reading, a song about a love that endures strong until the last moment, when suffering and death come to decree its physical end. The protagonist, who speaks in the first person, is a man who asks his beloved to make him dance until the end of love. It is to his woman that the protagonist addresses throughout the song. He asks her to make him dance through fear until he reaches a safe harbor. To raise him up like an olive branch, to be his dove that brings him home, to build shelter despite every finer thread being broken. Each image evoked by the song would deserve a commentary in itself, so profound are the metaphors through which the meaning of the song emerges. There is, however, one in particular that serves as the key to the entire song: the image of the burning violin, which the man asks the woman to play to mark the rhythm of this passionate dance.

In an interview with a Canadian broadcaster in 1995, Cohen stated that the image of the burning violin was suggested to him by the memory of the string quartets that, in Nazi concentration camps, were sometimes forced to accompany prisoners to the place of their performance. A dreadful image: musicians, even renowned ones, interned in the concentration camps, forced to perform in the most terrible of places, obliged to do what they loved best and to do it for the bleakest of purposes, namely to escort their fellow sufferers to their deaths, and often to witness the end they themselves were destined to suffer. It is well known that in concentration camps real orchestras of deportees were often formed, who were required to play to accompany other inmates to work, to welcome new arrivals, to entertain camp officials. And often, to accompany death sentences. Several photographs remain to offer us undeniable evidence of this gruesome custom.

|

| Leonard Cohen in 2008. Credit |

The story of one of these images is reconstructed during the Nuremberg trial. Testifying against the Nazis is a young Catalan photographer, 26-year-old Francesc Boix (Barcelona, 1920 - Paris, 1951). A socialist, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War, where he had fought in the ranks of the Republicans, and later an exile in France, he was captured by the Germans in 1940 while fighting in the French Foreign Legion. The Nazis sent him to Mauthausen: his entry into the Austrian camp is recorded as January 27, 1941, when 1,506 Spanish veterans arrived at the camp. He is not yet 21 years old.

The SS knows that Francesc is a photographer, moreover, an experienced one: in Spain he had worked as a reporter for Juliol magazine, the political organ of the Young Socialists, and despite his young age he had already been noted for his talent. Francesc is therefore assigned to the camp’s photo service: his main task is to develop the images taken in the lager. In return, he gets the chance to survive better and longer than many of his comrades. His boss is SS-Oberführer Paul Ricken, who decides how many and which pictures to take, and where and to whom to take them: arrests, executions, portraits of officers, visits, activities carried out by the condemned. There is not a moment in the life of the lager that Ricken does not want to document. Francesc thus has in his hands a huge legacy, which becomes even more valuable after the Axis defeat at Stalingrad in February ’43.

The commander of the camp, Franz Ziereis, under instructions that came directly from Berlin, orders Ricken to destroy all the negatives of the pictures taken at Mauthausen: the fortunes of the war have turned, the Soviets are beginning to advance westward, and there is a real fear that the Allies may reach the easternmost regions of the Reich. The Nazis, should the lagers fall into enemy hands, cannot leave compromising documents behind. It is above all the images of the atrocious deaths of prisoners that worry the Nazi authorities: it must be absolutely avoided that the enemies can get hold of them. Ricken delegates the task to Francesc, who begins to carry it out with zeal. But it is only an appearance: in fact, he decides to keep the negatives of the photographs he finds most interesting for himself. He knows full well that those images, so stark, so strong and so eloquent, can be aneffective weapon against the Nazis should they lose the war: they are immediate evidence of their crimes against humanity. Saving the photographs, however, is something he cannot do alone.

|

| Francesc Boix |

|

| Author unknown, The arrival of deportees at Mauthausen (1941; Koblenz, Bundesarchiv, Sammlung KZ Mauthausen, Bild 192-091) |

|

| Author unknown, Heinrich Himmler’s visit to the Mauthausen camp (1941; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

|

| Author unknown, The Lagerbordell, the Mauthausen brothel where female inmates were forced into prostitution (1941; Koblenz, Bundesarchiv, Sammlung KZ Mauthausen, Bild 192-349) |

|

| Author unknown, Arrival of Soviet prisoners of war at Mauthausen (1941; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

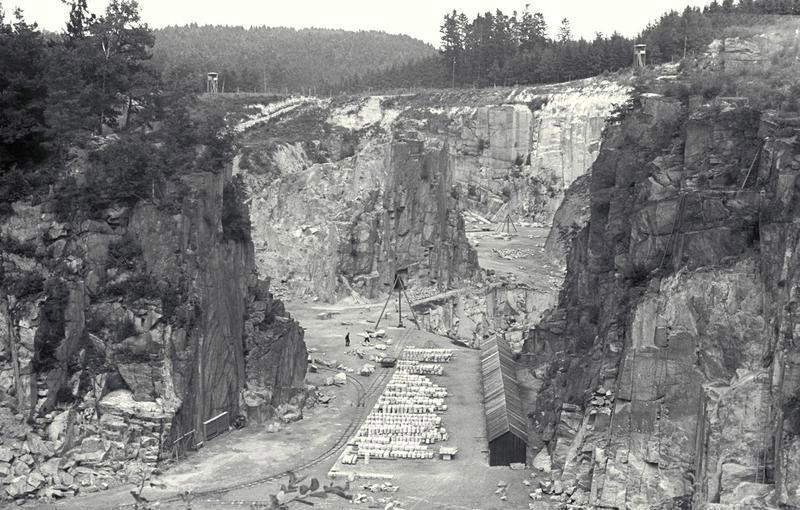

In total hiding, risking his life and having his friends and comrades risk it, he manages to convince other Spanish prisoners to help him hide the negatives stolen from the SS laboratory. He makes arrangements with another Catalan, Antoni GarcÃa, and a Madrid native, José Cereceda, to hide the photos in the most unthinkable, and therefore safest, places in the lager, where the Nazis cannot find them. But Francesc soon becomes convinced that the operation is extremely risky: keeping the photos inside the camp requires that attention be kept very high and means exposing oneself to constant danger. Thus, the young man arranges to get the cooperation of the Poschacher Kommando, a group of young men, his compatriots, forced to work in the quarries of the Poschacher company (which still exists), which are located outside the camp. They are required to return to Mauthausen every evening, but during the time they leave to go to work in the quarry they can enjoy a modicum of freedom. Involving the Poschacher Kommando boys means taking advantage of a unique opportunity to get the pictures out of the camp. It is, moreover, a pure matter of trust: they do not really know what those photos represent, because Francesc passes them wrapped inside sheets of paper, but the photographer assures his comrades that those wrappings contain very important documents. They go along with it, stash the negatives in their lunchboxes, and offer their crucial contribution to Francesc’s action, beginning by securing the photos in a shed where working materials for the quarry were being stored. And that’s not all: the Poschacher Kommando boys also manage to make contact with the inhabitants. They manage to get to know, towards the end of 1944, a local woman, Anna Pointner, who comes from a family of socialist tradition and looks sympathetically on that group of young internees. She, too, becomes an accomplice in the theft of photographs. In fact, her home borders the land where the quarry is located: there is a fence separating her house from the property of the Poschacher company. One of the Kommando boys, Jacinto Cortés, learns that he will soon be assigned to other duties: he therefore gives Anna as many photos as he can gather, and she hides them inside a wall of her home.

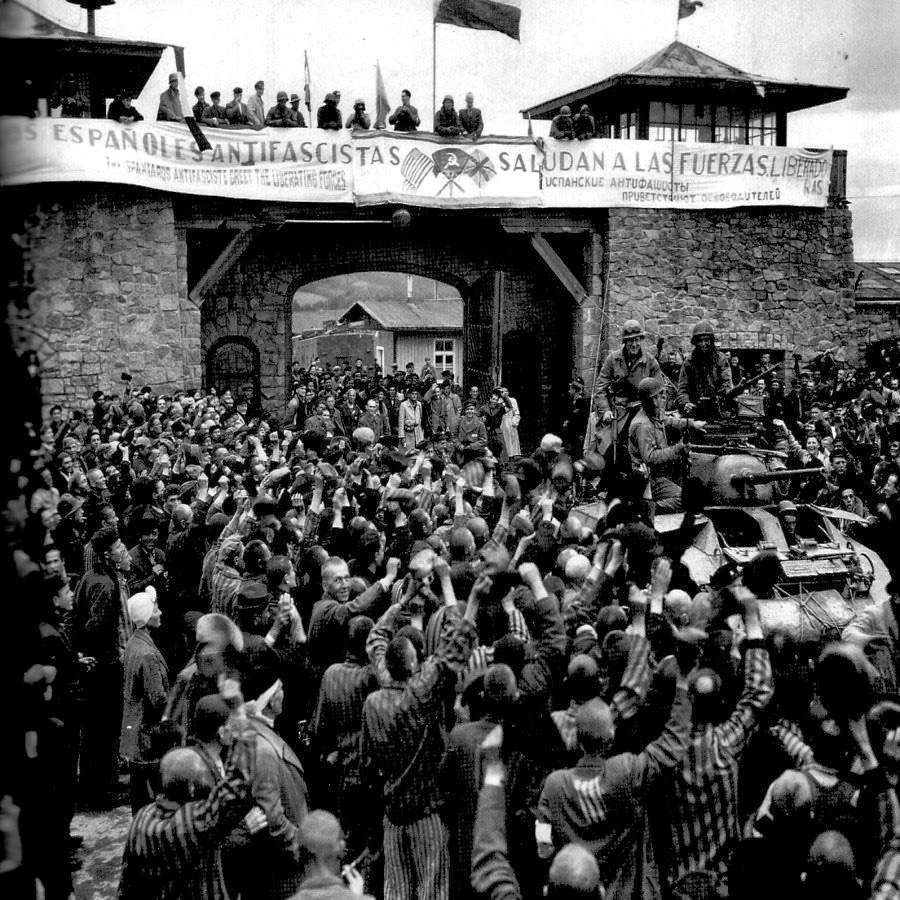

The Mauthausen camp is liberated by the Americans on May 5, 1945. Francesc survived, and some of the best-known photographs taken during the liberation moments of the lager are his work. With him, also surviving are the friends who made a personal effort, and risking their own lives, to bring the photos to safety: Antoni GarcÃa and José Cereceda, who were responsible for hiding the pictures inside the camp; Mariano Constante, one of the young men who knew of Boix’s plan and provided him with their support to cover it up; and Jacinto Cortés, Jesús Grau and José Alcubierre, the three boys from the Poschacher Kommando who were most involved. Alcubierre, the youngest of the group, was only fourteen when he was interned at Mauthausen and nineteen at the time of his release: an entire adolescence spent in the midst of horror. His contribution, moreover, had been crucial: it had fallen to him to collect the photographs Cortés and Grau passed to him, and to deliver them to Mrs. Pointner. When the war was over, they met at the lady’s house to collect the photos: the Spanish boys managed to get an impressive amount of pictures out of the camp. About twenty thousand, out of the total sixty thousand that made up the Mauthausen archive, at least according to Francesc Boix’s testimony. But it is difficult to make a precise estimate, because they were divided among different archives after the war. What is certain is that without the heroic act of Francesc and his brave friends, we might never have had visual evidence of what happened at Mauthausen. Most of all, what is impressive is the variety of images saved, documenting everything that happened in the Nazi camps. And which were brought as crucial evidence at the Nuremberg trial, where Francesc was the only witness of Spanish nationality. Today, much of the negatives are preserved in Barcelona, at the Museu d’Història de Catalunya.

|

| Author unknown, The Mauthausen Quarry (1941; Koblenz, Bundesarchiv, Sammlung KZ Mauthausen, Bild 192-031) |

|

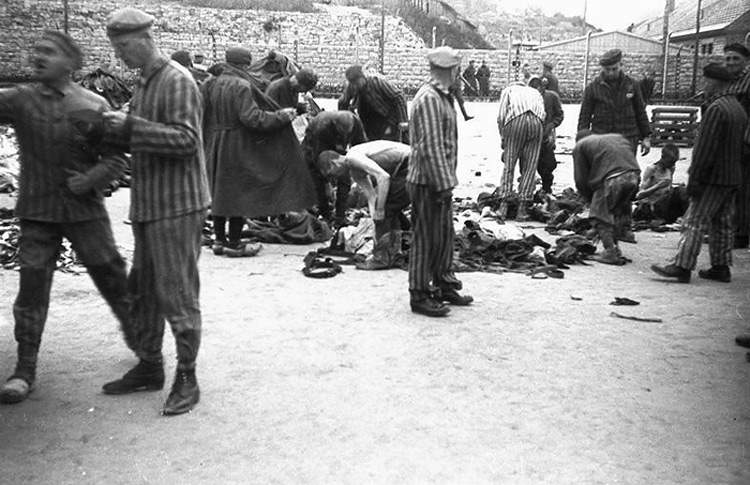

| Francesc Boix, Survivors at Mauthausen (1945; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

|

| Francesc Boix, The Liberation of the Mauthausen Camp (1945; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

|

| Francesc Boix, The Interrogation of Franz Ziereis (1945; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

|

| Francesc Boix, Mrs. Anna Pointner (first left) with her daughters and a group of Spanish survivors (1945; Barcelona, Museu d’Història de Catalunya) |

|

| Francesc Boix (center) with four other Spanish survivors (front, with Boix: Ramon Millà and LuisÃn GarcÃa. Behind: Jesús Grau and José Alcubierre) |

One of the most poignant photographs is one that recalls the image from Leonard Cohen’s song. We do not know if it was taken by Francesc Boix: presumably not. It is a shot that captures a sad procession to the execution site of an Austrian prisoner, whose name was Hans Bonarewitz. In June 1942 he had managed to escape from the camp: he had hidden himself in a crate that camp workers were to place on a truck, and the ruse allowed him to be transported far from the lager. His escape did not last long, however, since on July 11 he was found and handed over to the authorities. Ziereis himself wants to deal with his punishment, because the escape of an inmate is a very serious matter. The head of the lager orders him to be returned to Mauthausen immobilized inside the crate, worrying only about keeping him from suffocating. Upon arrival, he is forced to pass through two wings of prisoners, while a little orchestra prepared for the occasion provides the soundtrack for his torture. Poor Hans is then beaten savagely by the SS, receives twenty-five lashes, and is finally chained to the Klagemauer, the “weeping wall,” or wall in front of which prisoners were required to line up, usually upon arrival. On the second day, Hans is placed on a cart, in front of the crate he had used to leave the lager, and is escorted to the gallows always amid the notes of the little orchestra assigned to escort him. It is precisely the procession preceding Hans Bonarewitz’s hanging that is documented in the photograph.

|

| Author unknown, Hans Bonarewitz led to the gallows on July 30, 1942 (1942; Koblenz, Bundesarchiv, Sammlung KZ Mauthausen, Bild 192-249) |

“This,” Francesc Boix declared to the Nuremberg draft, "is a masquerade made with an Austrian who had escaped. He was a carpenter in the garage, and they set up a box there where he could hide to get out of the camp. However, after some time he was caught. They put him on the cart that was used to transport the dead to the crematorium every day. There were signs in German saying Alle Vögel sind schon da, meaning ’all the birds come back.’ He was condemned, and marched past ten thousand deportees. There was an orchestra of gypsies who, all the while, had been playing J’attendrai. When he was hanged, his body was swinging because there was wind, and they played a very well-known music called Bill Black Polka."

Perhaps, we cannot even conceive of the atrocity of the gruesome staging, laden with vicious cynicism, that accompanied the torture and execution of Hans Bonarewitz. And it is almost impossible to imagine the state of mind of those forced to see their passion, the art they love, turn against them because they were forced to practice it in the midst of horror. Several internees drew relief from music in the death camps. They found it to be the only glimmer of humanity in the hell of the Nazi concentration camps, and entrusted those sad notes with some shred of hope. But for many others it was not so. Several musicians who survived the death camps had long hated music. Such was the case for Szymon Laks, a talented Polish violinist who was commissioned to conduct the Auschwitz camp orchestra. “Music, the most sublime expression of the human spirit,” he wrote in his memoirs, “was also entangled in the hellish enterprise of the extermination of millions of people, and even played an active role in this extermination.” And it seemed to him that music provided no relief, indeed: he believed that that was a means of increasing the suffering of the prisoners. A way to make that annihilation of the person that the Nazis wished for the internees even more heartbreaking. To be forced to listen to that “burning violin” must have been an unbearable torment for those who had dedicated their lives to art, for those who cultivated a passion for music, for those who were simply endowed with a sensitive soul.

Reference bibliography

- Carlos Hernández de Miguel, Los últimos españoles de Mauthausen, Ediciones B, 2015

- Leonard Cohen, The lyrics of Leonard Cohen, Omnibus Press, 2009

- Montse Armengou, Ricard Belis, El comboi dels 927, Rosa dels Vents, 2005

- Janina Struk, Photographing the Holocaust. Interpretations of the Evidence, I.B. Tauris, 2004

- Benito Bermejo, Francisco Boix, el fotógrafo de Mauthausen, RBA Libros, 2002

- Szymon Laks, Music of Another World, Northwestern University Press, 2000

- Frediano Sessi, Auschwitz 1940-1945. Everyday horror in a death camp, BUR, 1999

To the story of Francesc Boix was dedicated the documentary Francisco Boix, un fotografo en el infierno and the exhibition Més enllà de Mauthausen at the Museu d’Història de Catalunya in Barcelona.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.