The Museum of Computing Instruments and the Museum of Physics Instruments at the University of Pisa.

TheUniversity of Pisa was officially founded in 1343, but already in previous centuries the city was frequented by students taking classes with celebrated masters, among whom was mathematician Leonardo Fibonacci. This ancient institution cloaked in great prestige also boasts an extraordinary patrimony of movable and immovable property, a significant testimony to which are the nine museums that are part of the Sistema Museale d’Ateneo, to which is added the Museum of Natural History of Calci, which, however, stands as an autonomous center.

Some have origins that go back centuries, several saw the light of day in the 19th century, while still others are far more recent. Among those not so old are two collections that initially had a shared museum history: they are the Museum of Computing Instruments and the Museum of Physics Instruments.

It all began in 1989 when the University of Pisa’s Department of Physics gave birth to the Center for the Conservation and Study of Scientific Instruments, with the goal of collecting, recovering and restoring the Department’s scientific instruments, an initiative created to protect them and avoid dispersion. And from the beginning, the same was done with the calculating machines, with the desire to document the evolution of the history of calculus through its very instruments. Thus there was a desire “to set up a modern museum of national importance aimed at the preservation and study of specimens of calculators and, more generally, of everything that has been made and written in the area of computing.” For this purpose, in 1993 the Ministry of Universities and Scientific and Technological Research decided to set up a national commission for the Museum of Computing Instruments, which issued a circular to all Italian universities and research institutes the following year to collect obsolete computer material. Thus, to the already substantial nucleus of more than 700 scientific instruments dating from the 17th to the 19th century, several thousand computational instruments were added, effectively forming one of the largest collections in the country.

The museum, which was initially housed in some rooms of the Department of Physics, was then opened in September 2000 in the area of the city’s Old Slaughterhouses, and although the collection gradually became larger and larger, it was only accessible by appointment. While in 2011 the museum of computational instruments by obtaining funds is opened on a regular basis also devoting itself to teaching and other activities.

Finally, in 2017, it was established by rector’s decree that the scientific instruments of physics and astronomy were to be collected independently, thus giving birth to an additional institution, the Museum of Physics Instruments. Thus, the first to come into existence is the Museum of Computing Instruments, a choice that is not accidental since Pisa has made a fundamental contribution to the development of modern computing, as can also be read in the collection on display.

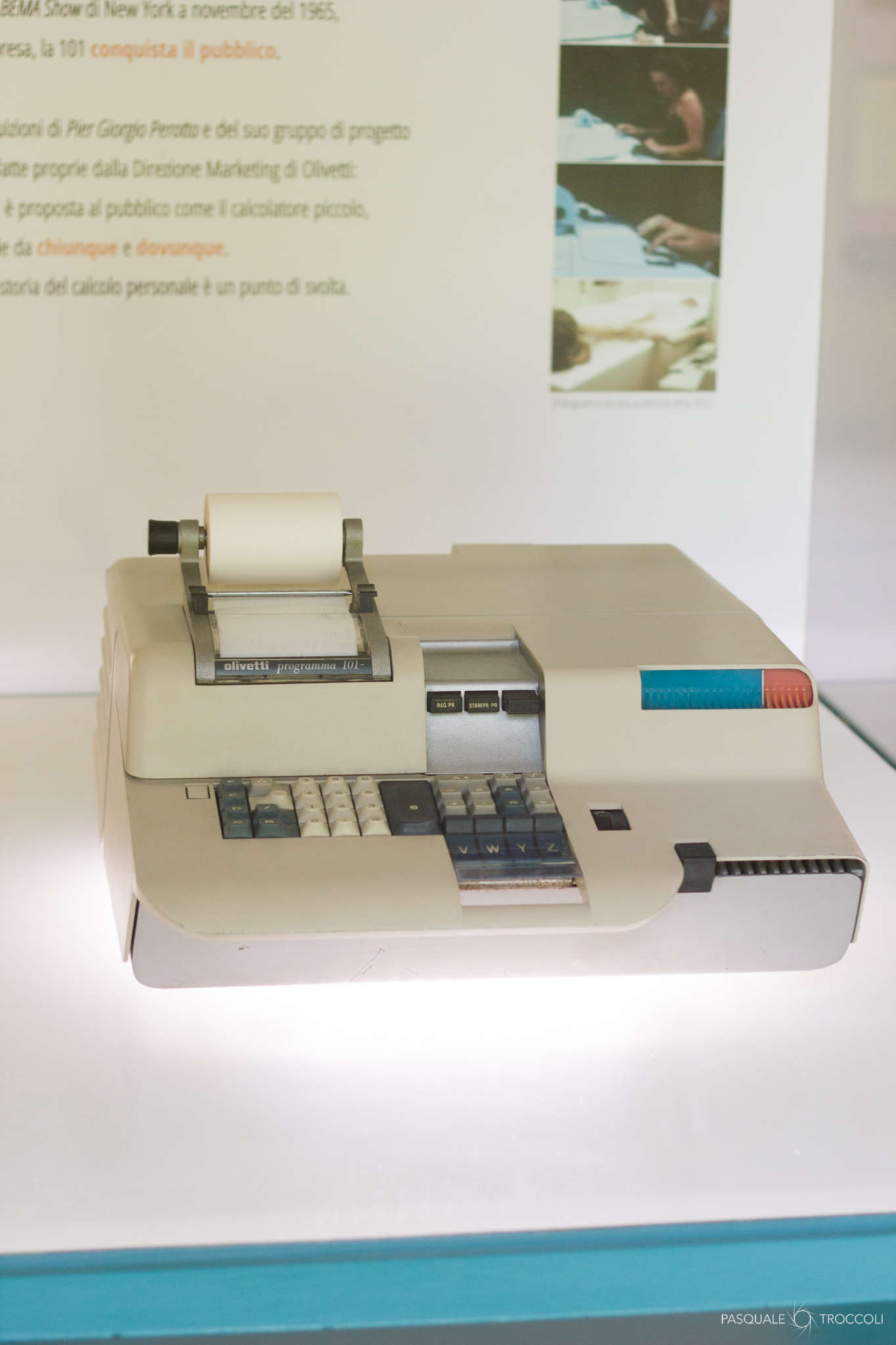

The collection consists of instruments prepared by mankind over some five centuries of history to facilitate computational operations: ranging from abacuses, compasses, to arithmometers, mechanical calculating machines that arose in the 19th century, among which the museum exhibits theArithmomètre Thomas, an early example of an 1850s calculator, and the Burroughs of 1895, as well as numerous other large and small machines that require manual action to operate.

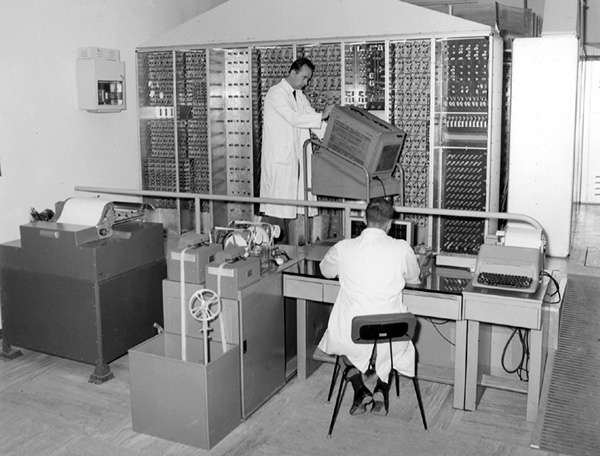

Early electronic calculators, on the other hand, were of considerable size: an example is the important Pisan Electronic Calculator (C.E.P.). The idea of purchasing a modern electronic calculating machine for the Athenaeum was put forward in the 1950s by Enrico Fermi, but since the funds allocated for this purpose were not sufficient, it was therefore decided to build it on site, and therefore the Center for the Study of Electronic Calculators was established in which over sixty people worked. The construction of the machine was also supported by the Olivetti company, which immediately showed interest, providing skilled workers in addition to a financial contribution.

At first only a reduced prototype was made, while in 1960 the actual machine was also completed, occupying about 70 square meters, and was inaugurated the following year in the presence of President of the Republic Giovanni Gronchi. The potential of the instrument was highly advanced, thanks to its high computing speed and large rapid memory capacity. Precisely because of this enormous instrument, the first school of computer science in Italy was formed in Pisa. Among the computers in the museum, the Olivetti ELEA 6001 calculator, also known for its iconic design curated by Ettore Sottsass, also deserves a mention, and of which one hundred and seventy examples were sold in Europe in spite of its immense cost, which reached as high as 500 million liras. Another cult instrument is also the CRAY XMP, a supercomputer that when it was built in 1984 was the most powerful and expensive, on which, moreover, the first Pixar shorts were made. The itinerary then also consists of ordinary calculators, microcomputers, and several personal computers and their devices, testifying to a continuous and sudden evolution of the world of computing that would later spread, becoming a ubiquitous prosthesis of our lives. The museum has the undoubted merit of showing us how this technology that we now take for granted instead has a complex and detailed history behind it.

Also of great interest is the collection of the Museum of Physics Instruments, whose exhibits are far older than those in the museum previously surveyed. These are heterogeneous artifacts, responding to various applications in the fields of physics. The nucleus of the oldest instruments was transferred from Florence to Pisa by Carlo Alfonso Guadagni, the first director of the chair of experimental physics in the 18th century, and some were made by the scientist himself. Coming instead from the gallery annexed to the botanical garden is the Musschenbroek Pneumatic Machine (1697), a gift from Princess Anna Maria Ludovica de’ Medici; it is an instrument built in Leiden by Jan van Musschenbroek, a “pump for the rarefaction of air” that made possible the experiments to demonstrate the existence of a vacuum.

The oldest exhibits also include an areometer, an apparatus used to measure the specific gravity of liquids and solids, from the 17th century, devised as part of theAccademia del Cimento, an institution founded in 1667 on the initiative of Prince Leopold de’ Medici and his brother, Grand Duke Ferdinand II. This entity was particularly important for the evolution of mathematical, astronomical, physical and natural sciences, as well as celestial mechanics, optics and human and plant physiology.

The founding core of the collection is also that which belonged to Antonio Pacinotti, a Pisan scientist, senator and professor at the University of Pisa; he is remembered as the inventor of the dynamo and the DC electric motor. Some of his prototypes of electromagnetic machines are preserved in the museum, such as the famous Macchinetta (1860), or dynamo. Then again, the Electromagnetic Ball and Flywheel Machine, and other electromagnetic attraction equipment, which show how Pacinotti was the first to idealize linear motion that harnessed that force.

Also significant among the approximately 800 instruments in the collection are the Machine for the Study of Centrifugal Forcesfrom the first half of the 18th century, the Machine for the Study of Induced Currents, Matteucci’s Commutator, an instrument designed to straighten alternating currents from the mid-19th century, and Cavallo’s Electrostatic Machine from the previous century. From the Specola Pisana, on the other hand, come some astronomical instruments with which most observations were conducted, such as George Graham’s clocks and the wall quadrant.

Coadjutating and complementing the activities of the museum is the LuS, a science toy library that promotes its activities in a shed at the Macelli, where through a collection of games and instruments created to reproduce, in an all-Galilean spirit, the experiments that have made the history of science and scientists, children are brought closer to the world of physics and science in general through fun.

Both museum entities, the Museum of Computing Instruments and the Museum of Physics Instruments, constitute not only a meaningful encounter with science, but a chance to learn about the history of a city and its university whose contributions are still studied today.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.