On the Lungarno Simonelli in Pisa, inside what used to be the Arsenali Medicei, the Museum of Ancient Ships will be located as of 2019. A name that will perhaps say little to many, but which in reality hides one of the richest and best-kept archaeological museums in Tuscany, as well as one of the most important museums in the world on the subject of navigation and the sea, created at the behest of the local Soprintendenza and the current director Andrea Camilli around an archaeological context that is nothing short of extraordinary, that of San Rossore in Pisa, whose excavation began in 1998. A museum that, whether you are an archaeologist or not, is well worth a long visit.

The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships ofThemuseum is almost disorienting to the visitor because of its vastness, spanning under the bays of the Arsenals for almost 5,000 square meters of exhibition space, 47 halls and micro-halls divided into 8 sections, about 800 artifacts for a museum aimed at recounting “a millennium of trade and sailors, routes and shipwrecks, navigations, life on board and the history of the city of Pisa,” as the Ministry website writes. Beginning with the exhibits at the heart of the display, the seven ancient-age vessels that give the museum its name, dated between the 3rd century B.C. and the 7th century A.D. which stand out in the largest room, the fifth section of the museum, the Museum of Ancient Ships has succeeded in creating a space that is much more than a museum of navigation, and that through a careful selection of the exhibits, unobvious but effective display choices (such as theuse of dioramas or digital and color games), and a respectful but non-invasive dialogue with the structure of the Arsenals, allows for a multi-level visit, and why not multiple visits.

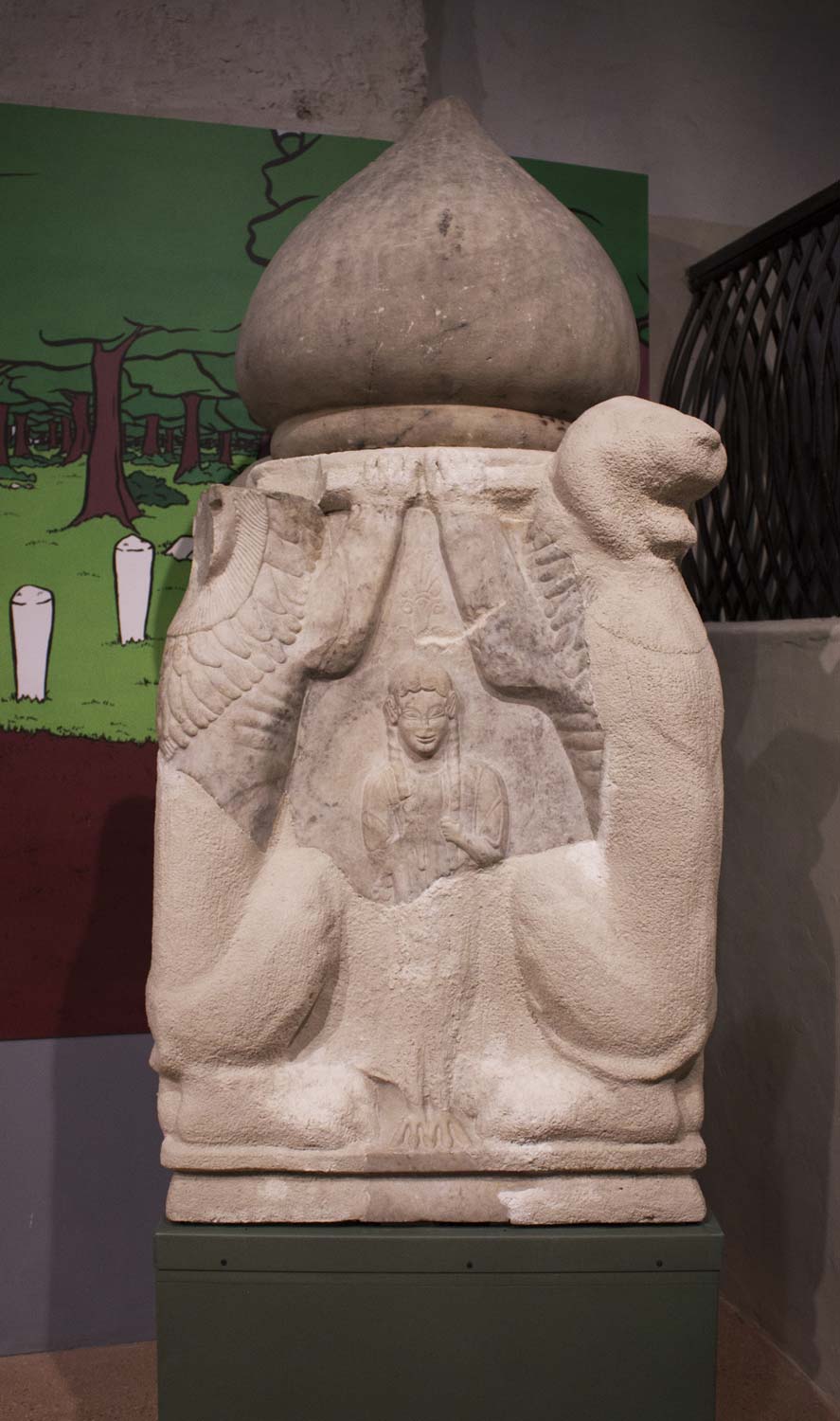

The first section is in fact dedicated to the city of Pisa, with a series of maps, videos and artifacts that tell the story of “the city between the two rivers” (the Arno and today’s Serchio), the development of Pisa as a port city (a role it maintained until the birth of Livorno in the 16th century) from the Etruscan period of its founding to the Longobard age. A relationship that also unravels in the second section, which recounts and describes Pisa’s coexistence with water, with the environment and with the territory: the organization of the territory between canals and centuriations, the port, commercial activities and the hydrogeological impact of these intense activities, already in ancient times. In the third, floods and their victims are recounted, and from there on the stories of sailors. Navigation in ancient times is introduced , and in the fourth space is given to shipbuilding methods, again through a sequence of artifacts, documents and videos.

The fifth section, as mentioned, is where ships are exhibited, which is worth mentioning further: we find exhibited the Alkedo (the Seagull), from the name still engraved on a tablet, flagship of the Pisan fleet, from the first century AD, from 12 oarsmen for pleasure but with shapes reminiscent of a warship. Nave "I " (5th century AD), a large flat-bottomed river ferry entirely constructed of oak wood and reinforced on the outside by iron bands; maneuvered between the two banks by a system of ropes. It was moved from the shore by means of a winch, the central axis of which was found during excavations (displayed in the showcase next to the boat). Boat “F,” a smaller cargo boat used for quick and more comfortable travel and detail transport of goods. A vessel similar to pirogues, made to allow paddling on one side only, like the current Venetian consoles. The Nave "D," a large river barge of which the deck and mast are still clearly visible, used to transport rena along the course of the Arno. The vessel was propelled by sail (it still retains the original mast) and pulled from the shore by a pair of horses or oxen. And the skeleton of a horse still harnessed to it was found underneath it, and displayed next to it. Then a “Hellenistic” ship, in fragments, a medium-large cargo ship; a Barca “H”, a flat-bottomed river barque (2nd century B.C.), a medium-large cargo ship that shuttled along the coast between Campania and Spain and carried a cargo of amphorae (including pickled pork shoulders, displayed next door). And finally Nave "A," a large (oneraria) cargo ship (more than 40 meters long; about half of it was recovered) from the 2nd century AD. Because of its size, it was displayed by reconstructing part of the excavation site, showing it being recovered.

Also in the hall are 1:1 scale reconstructions of the ships whose remains are displayed. The room is exciting, enhanced by videos illustrating the workings of the ships on display, and may require a longer or shorter stay depending on the interests and skills of the visitor. As throughout the museum, the captions are basic but clear, allowing the visitor whether to choose to delve further, with a guide, or to conduct a quicker tour by grasping the main features but without tiring themselves with reading.

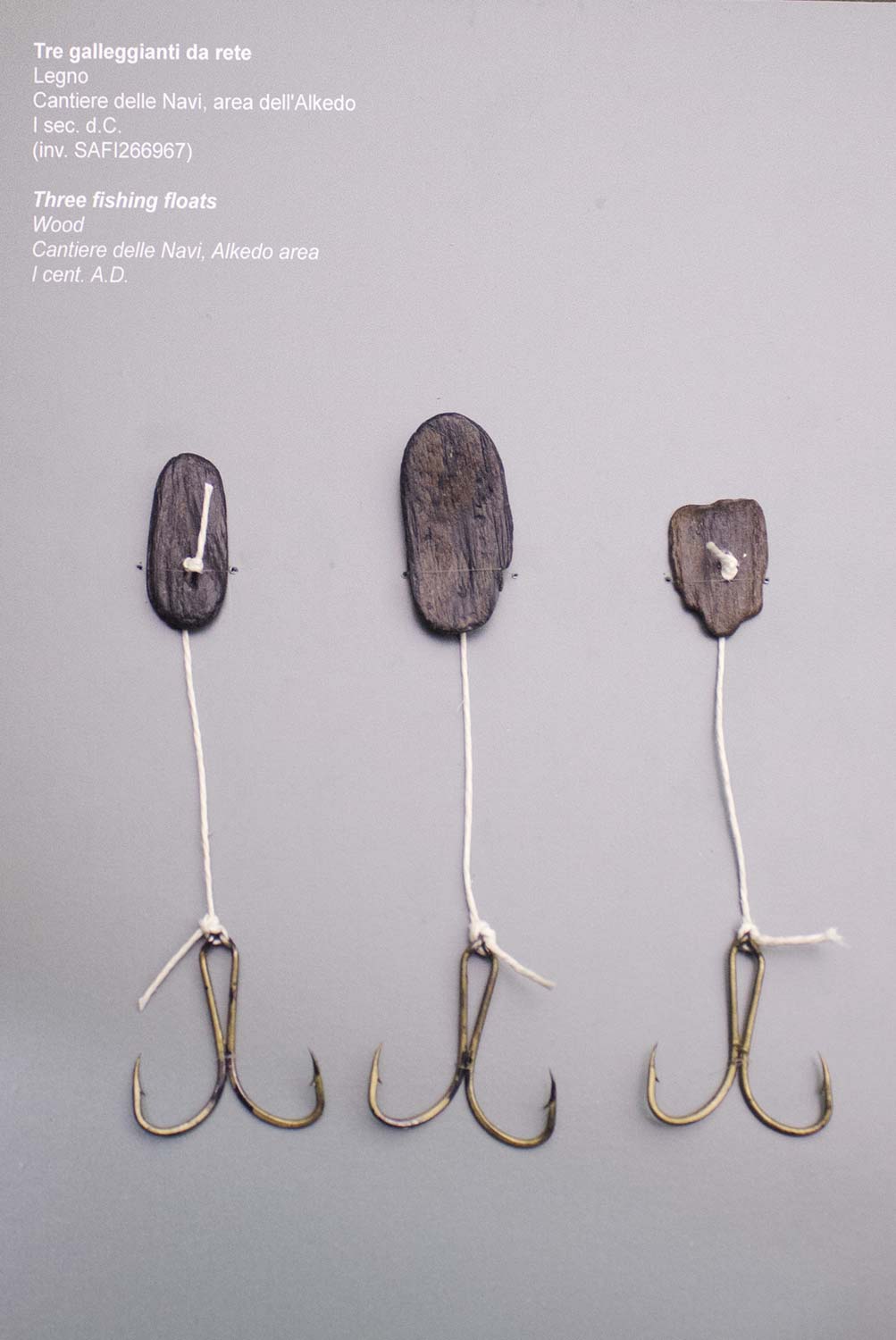

Three more sections then follow. One on trade, characterized by a wall of amphorae from different periods and provenances arranged by chronology and geographical area of origin that, besides being effective in terms of disclosure, ends up being rather “Instagrammable,” that is, suitable for souvenir photos, thanks to good color choices. This is followed by a section on navigation where more artifacts from the San Rossore excavation, sails and an anchor are displayed, while a display board illustrates the duration of voyages in Roman times. And it closes with a section on “life on board,” where thanks to the exceptional preservation of artifacts from San Rossore we find exhibited materials that are decidedly rare in an Italian (and other) archaeological museum: clothing, luggage, remnants of meals, children’s games, all contextualized in a coherent narrative that accompanies the visitor to the conclusion of the voyage.

The place where the museum is developed also deserves a mention: the Medici Arsenals, created at the behest of Grand Duke Cosimo I de’ Medici to consolidate Tuscan naval power and house the Order of the Knights of St. Stephen against the threat of Saracen armies. Arsenals that soon fell into disuse and became first military quarters, then stables for the mounts of the Dragoons, the Lorenese cavalry regiment, and after the Unification of Italy the horse breeding center of the Savoy state, which remained active under the Italian Army until 1965. The museum has chosen to preserve the structure of the Arsenals as much as possible, retaining, for example, the horse stalls, still complete with their troughs and gates, fragmenting the exhibition narrative, but allowing visitors to grasp the history of the building as well.

What, however, beyond everything else, makes the museum what it is, and in some way enabled its conception and birth, is the archaeological context of San Rossore, capable of returning an exceptional quality and quantity of artifacts now masterfully displayed among the rooms: and although this is an era in which “exceptional” discoveries flourish with an often excessive ease, due more to the need for media visibility than to the real exceptionality of the find, the San Rossore excavation undoubtedly deserves the adjective, for a multiplicity of technical and scientific reasons, since the context has delivered of a large quantity of objects preserved very, very rarely in archaeological contexts. Wood, textiles, hides, baskets--objects so rare, from winches to vests, that to the visitor unaccustomed to archaeology they might risk saying little, so unaccustomed is our eye to similar objects from the Roman era. The relevance to understanding the lives of the past, however, is extraordinary, and the museum devotes appropriate space to the context and explanation of how excavation takes place in wet environments, and why it is so difficult and rare.

The discovery of the context was in 1998, when work began on the Rome-Genoa railway at the Pisa San Rossore station. It was not difficult for the archaeologists then to realize that what they were uncovering was of exceptional significance: at a depth of six meters, an incredible array of shipwrecks emerged in an exceptional state of preservation, with their cargoes of commercial products and evidence of life on board. Covered by mud for 1,500 years, after the abandonment and silting up of the harbor followed the end of the Western Roman Empire and the wars of the sixth century AD. The mud and moisture had allowed their preservation.

The Pisa Roman Shipyard was then born, concluded in 2016, which has returned some 30 vessels, glass, metals, and indeed organic materials such as woods and skins. A shipyard that required considerable economic, organizational and technological effort, and became a center equipped with laboratories, storage facilities and instrumentation, now active behind the museum, which has collaborated and collaborates with various Italian and foreign university and research institutions. A judicious selection of everything that has been found and studied is on display at the museum.

The

The The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships of The Museum of Ancient Ships of

The Museum of Ancient Ships ofThe Museum of Ancient Ships is just beginning its life. It has a modern and engaging display, is equipped with a restoration laboratory, and should soon be joined by the Library of Ships, dedicated to naval and underwater archaeology and naval history, under construction in an adjacent building. It requires a lengthy visit, it is suggested that you start by budgeting a little more than an hour, but it deserves even more, because the stories it tells are many, but the museum workers will be able to answer your questions as well as, of course, offer you a guided tour. It succeeds in being a museum for everyone, thanks to the different levels of visitation and insight possible. Unless you loathe the idea of spending time among Roman-era ships, if you are passing through Pisa you cannot miss spending a few hours there.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.