The most famous "dickhead" in art history: history of the work of Francesco Urbini

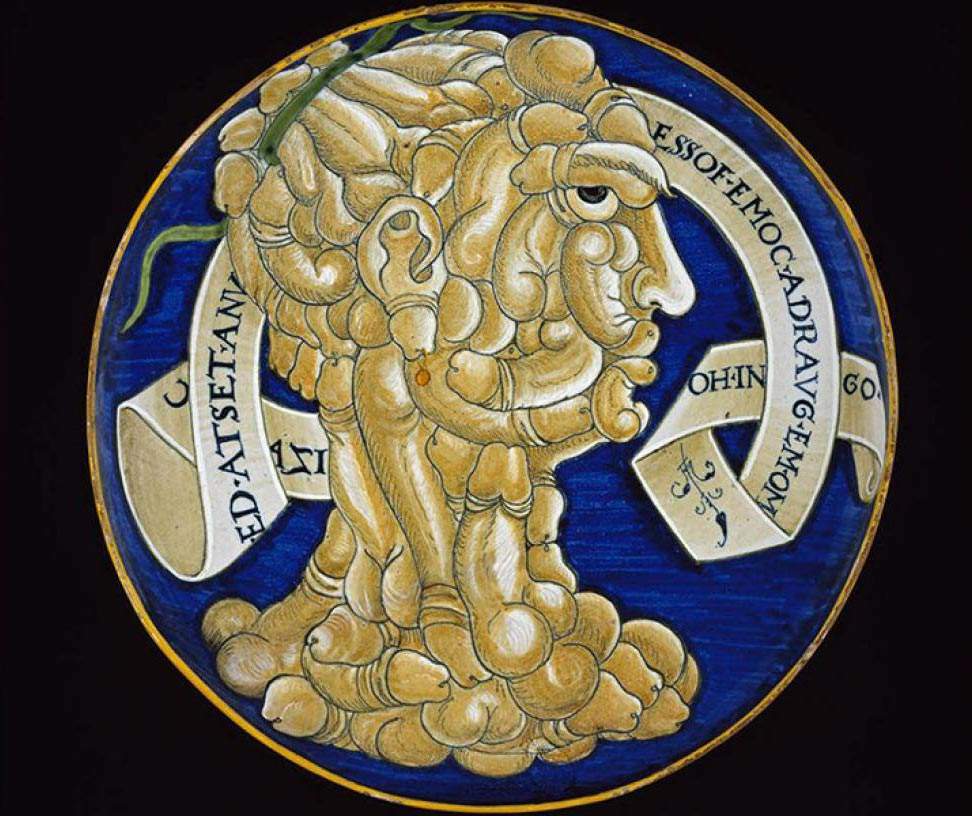

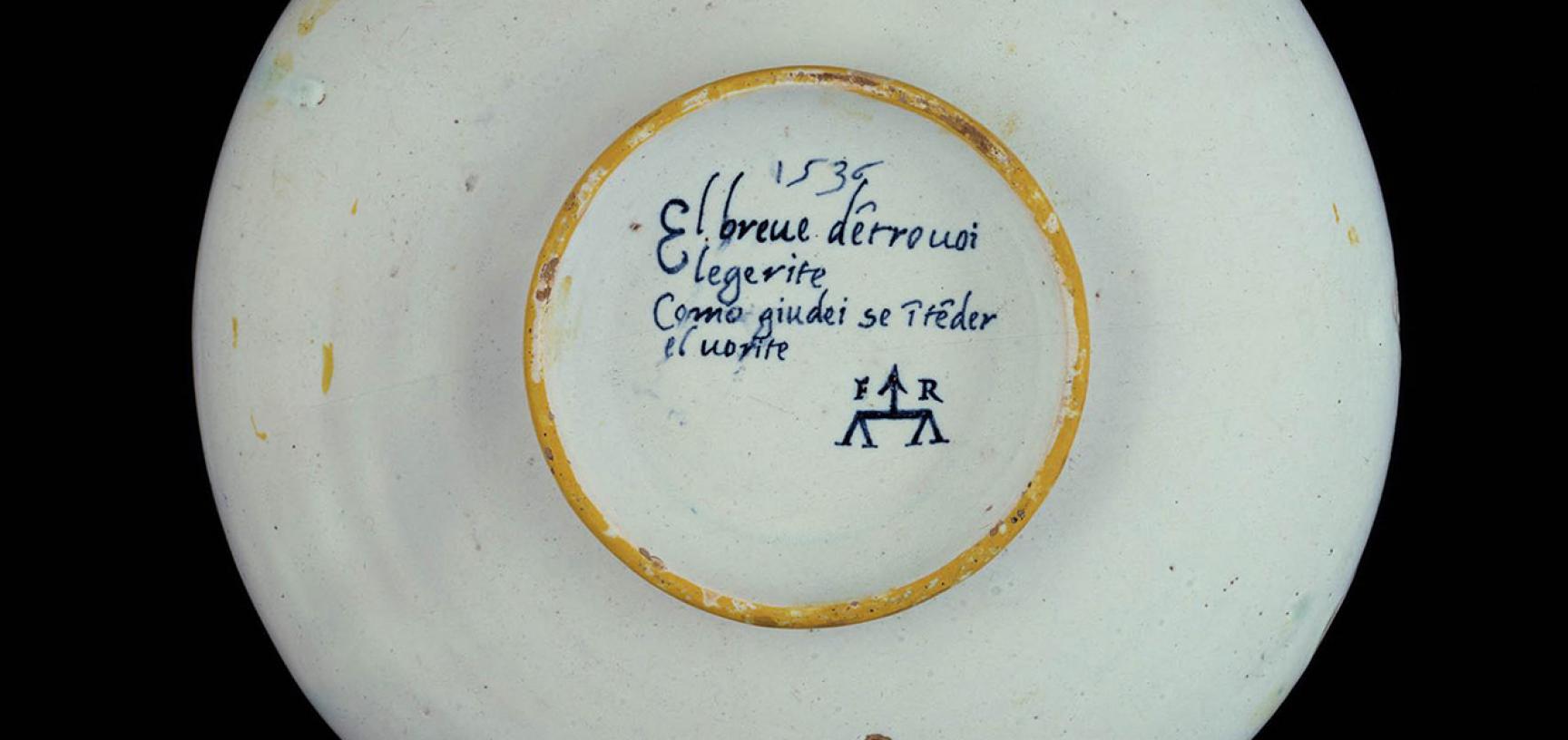

“Ogni homo me guarda come fosse una testa de cazi,” meaning “every man looks at me as if I were a head of cocks”: it is well guessed from the contemporary Italian translation of the cartouche that adorns the singular composite head of a half-unknown sixteenth-century Umbrian ceramist, a certain Francesco Urbini (Gubbio? first half of the 16th century), who has gone down in history for having created, in 1536, this incredible invention, one of the most irreverent works in the history of art, well in advance of the more famous composite heads of the Lombard Giuseppe Arcimboldi (Milan, 1527 - 1593), who was then but a child. It is a head made exclusively of penises and testicles, of all shapes and sizes: long, small, straight, curved, erect, limp. The object is a cup with a raised rim on a low foot: and on the foot it is possible to read an additional inscription, in which we also find the date when the artifact was made: “1536 / El breve de[n]tro voi legerite / Como giudei se i[n]te[n]der el vorite / F R” (i.e., “you will be able to understand the sentence if you are able to read like the Jews”). The two initials, “F” and “R,” the first two letters of the name “Francis,” were associated, wrote art historian Marino Marini, “to a majolica maker who worked in Gubbio, in the workshop of mastro Giorgio, between 1532 and 1535 (but possibly also in 1536) before moving to Deruta where, in 1537, he initialed a dish as ’fran[cesc]o Urbini’; the signature, however, does not clarify whether ’Urbini’ means the painter’s surname or place of origin.” The British scholar Timothy Wilson, who devoted a lengthy essay to the “cockshead” in 2005, has tried to reconstruct a hypothetical biography, believing that Francesco was active in Urbino, Gubbio and Deruta in the 1630s, first in the circle of Francesco Xanto, a ceramist from Urbino, and then at the workshop of that mastro Giorgio (i.e. Giorgio Andreoli) mentioned by Marini. Probably, according to Wilson, Urbini was a ceramist with an itinerant career and without a workshop of his own. Otherwise, there are no archival records on his figure. This is, ultimately, all we know about the maker of this dish.

“An historiated Casteldurante dish from 1536,” art historian Maurizio Calvesi describes it in his essay on Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s sources, characterized by “the vulgar artifice of hatching the heads with a bunch of phalluses. Heads of c[azzo], in other words, as explained, if any were needed, by the reverse inscription in the plate’s cartouche.” The bizarre phallic head, now housed in theAshmolean Museum in Oxford, but often exhibited recently in Italy as well (for example, in 2017 at the Arcimboldo exhibition held in Rome’s Palazzo Barberini, or at the important 2019-2020 Pietro Aretino exhibition at the Uffizi), has long raised questions among scholars, who have wondered why such a curious depiction was made, and from where the obscure Francesco Urbini got the idea of creating a head composed only of phalluses (“an example of a monothematic composed figure, that is, of an image defined by a single element repeated several times,” according to art historian Giacomo Berra’s effective definition).

|

| Francesco Urbini, Plate with Composite Head of Phallus (1536; majolica, diameter 23.3 cm, height 6.1 cm; Oxford, Ashmolean Museum) |

|

| The verso of Francesco Urbini’s plate |

Meanwhile, where had Francesco Urbini derived the idea of creating such a head? To answer this question, a premise on the history of Casteldurante ceramics is first necessary: at that time, in the first decades of the sixteenth century, so-called “beautiful women” were widespread in the town in the Marche region (today’s Urbania) and, more generally, throughout the Duchy of Urbino: they were female portraits, not necessarily realistic or reproducing the features of the woman depicted, that men gave to women as a flattering tribute. Usually, the portrait (three-quarter or in profile) was accompanied by a cartouche bearing the woman’s name accompanied by the adjective “beautiful” (or simply a “b”): from this custom comes the name by which this type of majolica is known. Francesco Urbini’s “head of cocks” seems to respond perfectly to this type: not only does the presence of the cartouche and the appearance of the figure recall “beautiful women,” but it is almost certain that the “cockshead” is a woman, since she wears a coral earring (a typical female ornament) and the phalluses that make up her hair are arranged to create a hairstyle gathered with a ribbon and pulled back, also typical of Renaissance women (in the Contini Bonacossi collection in Florence, which is part of the Uffizi Gallery’s collections, it is possible to find a portrait of a certain “Hippolyta” who has a hairstyle identical to that of the “head of cocks”).

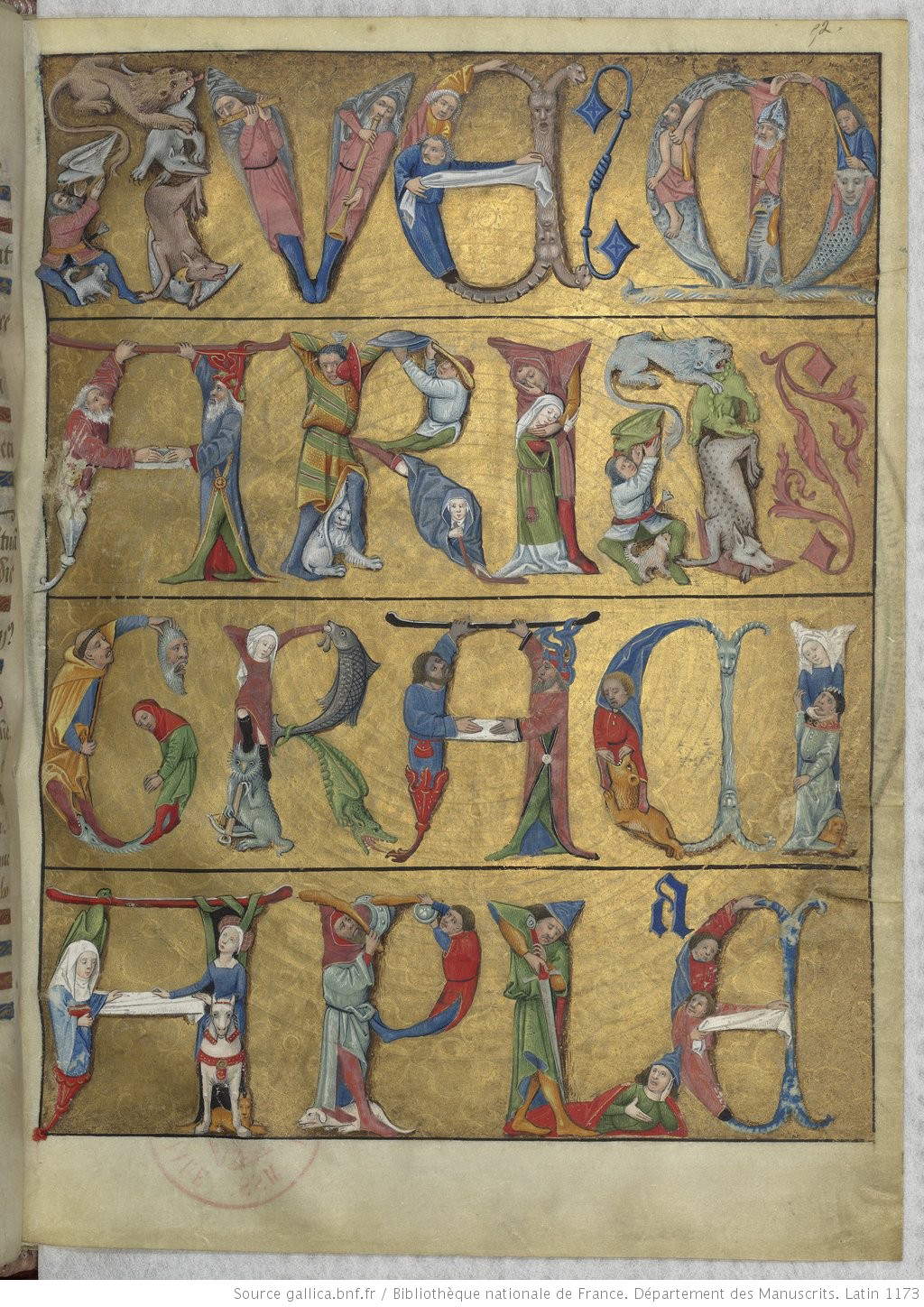

Having thus brought the context into focus, it remains to be clarified from where Francesco Urbini had drawn the design of a composite head. In this case it must be said that the idea of creating figures composed of other, smaller figures is not an invention of the Umbrian ceramist: for Urbini (as well as for Giuseppe Arcimboldi’s composite heads) the precedents are to be found in the "figured alphabets," that is, letters of the alphabet created with compositions of several figures combined with each other, and found in great abundance in illuminated codices, from very ancient times. “By a figured alphabet,” Berra further writes, “is meant an alphabet whose letters are formed by objects, animals, human figures, etc., which together accurately define the overall shape and layout of the single letter. In the simplest cases the letter may consist of a single element (e.g., a fish for the letter ’c’), but in most cases the individual letters are recreated through the association of several shapes arranged in creative and imaginative ways.” The origins of figured alphabets go back as far as the 6th-7th centuries AD (at that time, figured alphabets were composed of animal figures), and to find similar compositions with the human figure inside, we have to wait until the 8th-9th centuries, where ornaments with human beings appear simultaneously in Rome, the Carolingian Empire and the British Isles. Until the sixteenth century, these jaw-dropping compositions were known only to connoisseurs of books; with Francesco Urbini they arrive on majolica, and later, with Arcimboldi, they would enjoy great success in the circles he frequented precisely by virtue of their ironic and surprising character, which lent itself to pranks, jokes and assorted mockery.

It might then not be so peregrine to suggest that Francesco Urbini was familiar with the grotesque heads of Leonardo da Vinci (Vinci, 1452 - Amboise, 1519), the caricature portraits that abound in his folios and enjoyed an extraordinary fortune until the seventeenth century: This is attested to by the numerous replicas that various artists made of these Leonardian figurations that exaggerated certain features of the human face (as well as the fact that they were widespread among artists in Leonardo’s circle), and also identified by several scholars as one of the sources of Arcimboldo’s composite heads. Some of these Leonardo “capricci” were also erotic in subject: this is information we get from Giovanni Paolo Lomazzo, because to date there are no known erotic-grotesque compositions by the Tuscan artist. But we can catch an echo of it in a sheet preserved at the Pierpoint Morgan Library in New York, the work of Cesare da Sesto (Sesto Calende, 1477 - Milan, 1523), a pupil of Leonardo: here, we see a grotesque head similar to that of a lion, which, however, is nothing more than a young man practicing fellatio on his own, and what appears to be the animal’s snout are actually the boy’s two buttocks and scrotum seen from behind. Probable, then, that similar precedents are to be identified as the figurative sources that Francesco Urbini drew on.

|

| Giuseppe Arcimboldi, LEstate (c. 1555-1560; oil on canvas, 68.1 × 56.5 cm; Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen) |

|

| Anonymous Casteldurante potter, Dish of “bella Livia” (1930s; majolica, diameter 21.5 cm; New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art) |

|

| Anonymous potter, Dish of “Ippolita” (first half of the 16th century; majolica; Florence, Uffizi, Contini Bonacossi Collection) |

|

| Anonymous, Book of Hours of Charles d’Angoulême (15th century; Paris, Bibliothéque Nationale, Ms. lat. 1173, f. 52r) |

|

| Bottega di Giovannino de’ Grassi, Alphabeto figurato, in Taccuino dei disegni (last quarter of the 14th century; Bergamo, Biblioteca Civica Angelo Mai, Cassaf. 1.21, f. 29v.) |

|

| Leonardo da Vinci, Grotesque Couple (77 x 4.7 mm and 76 x 47 mm; Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana, F 274 inf. no. 27a and F 274 inf. no. 27b) |

|

| Cesare da Sesto, Studies for Mars, Venus and Cupid; Adam and Eve; a grotesque; other figures (c. 1508-1512; pen and brown ink on paper, 197 x 143 mm; New York, Pierpoint Morgan Library) |

Instead, to understand the tone of the composition, it is imperative to step into the cultural context of the intellectual circles of the early 16th century, where it was very common to employ images from the erotic and sexual repertoire for burlesque purposes: and this in art as in literature. In a recent essay by Antonio Geremicca, published in the catalog of the exhibition Giulio Romano. Art and Desire, held in Mantua between October 2019 and January 2020, a passage from a letter sent on January 31, 1515, by Niccolò Machiavelli to Francesco Vettori is quoted: “he who would see our letters, honored fellow, and see the diversity of them,” wrote the great man of letters, “would be greatly astonished, because it would seem to him now that we were grave men, all turned to great things, and that in our breasts no thought could fall that did not have in itself honesty and greatness. So then, turning paper, it would seem to him that we ourselves were light-hearted, inconstant, lascivious, turned to vain things. This way of proceeding, if it seems to some to be vituperative, seems to me laudable, because we imitate nature, which is varied; et he who imitates that cannot be taken back.” In short: even the greatest intellectuals are capable of descending to the lowest levels, Machiavelli seems to say, bringing back a thought that never goes out of fashion. These lowest levels, these thoughts “leggieri, inconstanti, lascivious, turned to vain things,” are also those of the more or less explicit sexual allusion, which in the Renaissance enters rightfully into high culture, on the heels of the successes of the burlesque poetry of the fifteenth century. At first through codes readable only by those who knew them, and then in an increasingly open manner. “It is by passing through a back door,” Geremicca writes, “that intercourse, phallus, and female genitalia pass through the barricaded gate of high culture, and that ’huomini gravi’ could, at one time, be ’lascivious.’”

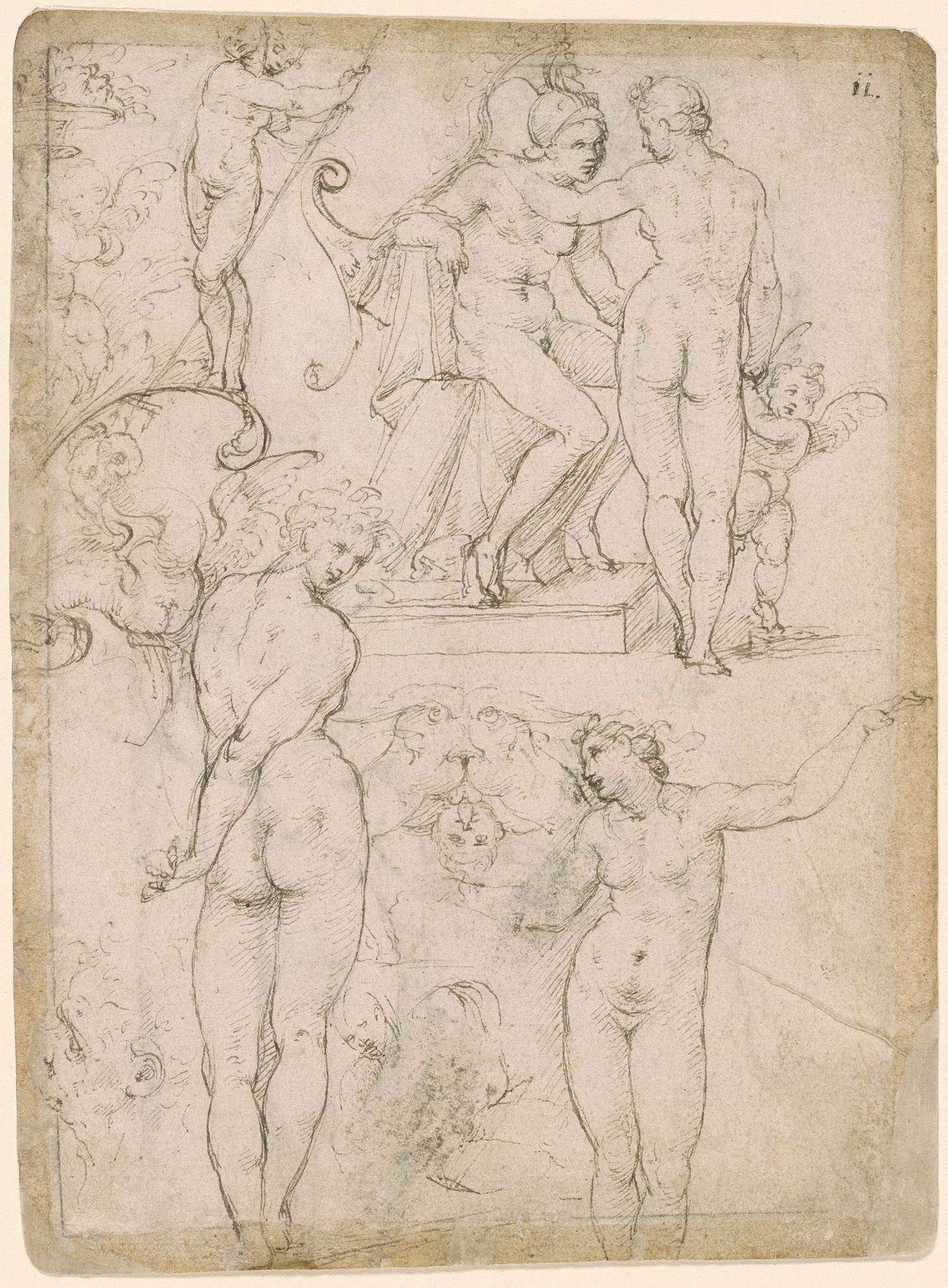

Great (and serious) men of letters such as Benedetto Varchi, Lodovico Dolce, Annibal Caro, even Monsignor Giovanni Della Casa delighted in burlesque poetry. Some of them got together in a sodality, the so-called “Realm of Virtue” (Caro and Giovanni Della Casa, among others, were members), which organized golidardic dinners where jokes, even heavy ones, were exchanged, often about sex. About sex, in short, they laughed. It is in this spirit that we should read two works by Francesco Salviati (Florence, 1510 - Rome, 1563), presumably dating from the 1540s, and participating in the same cultural climate as the “dickhead.” The first is a Triumph of the Phallus, in which a member of unusual proportions is carried in glory by a festive procession of maenads, cupids, chariots, animals, allegorical personifications (there is even a winged victory that is engulfing the glans of the penis), in imitation of ancient reliefs that had as their subject triumphs of distinguished personages or deities: and here the deity is nothing more than a huge phallus, and no great feats are celebrated, but simply the pleasures derived from the use of the protagonist of the triumph. Even more surprising is a second drawing, a phallic head similar to that of Francesco Urbini, so curious that it has also been attributed in the past to Leonardo da Vinci.

We do not know if there is any relationship between Salviati’s pen drawing and Urbini’s majolica: more likely, however, is that the Florentine painter’s work is related to a medal by Pietro Aretino, made with satirical or disparaging intentions toward the great writer, and which features on one face a portrait of Pietro Aretino (Arezzo, 1492 - Venice, 1556), and on the reverse a satyr’s head with hair taking the shape of phalluses. On this work, critics are divided: perhaps it is a way of calling Pietro Aretino a “phallus head,” a character who enjoyed many sympathies but who also knew how to arouse strong hatred, especially in ecclesiastical circles, so much so that in 1525, in Rome, he was the victim of an attempted murder that convinced him to leave the capital of the Papal State to move permanently to the freer Venice, where he would spend the last thirty years of his existence. If, therefore, this is how it is to be interpreted, it is possible that it was produced in an anti-Aretino context, probably behind the direction of Niccolò Franco (Benevento, 1515 - Rome, 1570), a man of letters who was a fierce opponent of Aretino, to the point of insulting him with a collection of sonnets entitled Priapea (Niccolò Franco had nicknamed his rival “flagello de’ cazzi” in response to the well-known epithet “flagellum of princes” with which Ariosto had defined Aretino) and where the man of letters from Arezzo was the object of jokes with erotic subjects (and it could not have been otherwise, since Aretino was a prolific author of erotic literature, beginning with the celebrated Lustful Sonnets, written to illustrate Giulio Romano’s Modi, the famous engravings illustrating sixteen erotic positions). But the medal could also have been made on Aretino’s own commission, as a celebration of an author who knew how to be self-mocking and who gave proof that he did not take himself seriously. This hypothesis could be supported by the inscription we read beneath the satyr, Totus in toto et totus in qualibet parte (“All in all and all in all parts”), a Neoplatonic formula that alludes to the union of soul and body.

Finally, it is worth noting how examples of “beautiful woman” reinterpreted in an erotic key were not alien to Casteldurante majolica. The Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington preserves a plate in which a young woman appears, portrayed as per the typical iconography of “beautiful women,” accompanied, however, by a cartouche that reads “Piglia e no penetire, pegio no po stare che a restituire” (which we could translate in current Italian roughly as follows: “take it and don’t regret it, at worst you’ll have to give it back”). A clear allusion to thebird that the girl holds in her hands, and we all know very well what the allusive meaning of the word “bird” is: in the sixteenth century it was the same as it is today. In sixteenth-century ceramics there is also no shortage of erotic scenes not necessarily ascribable to the genre of the “beautiful woman”: several examples can be found in various collections. For example, in the French state collections we find two majolica pieces from the Grand Palais, one depicting the beginning of a carnal union between a couple (where we see the man with a conspicuously erect penis), and the other where we see a young woman plucking from a field some very singular fruits, namely penises, all accompanied by the unmistakable inscription “Ai bons fruti, done.”

|

| Monogrammist CLF (from Francesco Salviati), Triumph of the Phallus (1700-1750?, etching, 448 x 1642 mm; London, British Museum) |

|

| Francesco Salviati, Phallic Head (1541-1543, pen with white highlights; Private collection) |

|

| Anonymous, Medal of Pietro Aretino (after 1536; bronze, 47.6 mm diameter; Florence, Museo Nazionale del Bargello) |

|

| Anonymous potter, Erotic Scene (16th century; faience; Paris, Grand Palais) |

|

| Anonymous ceramist, Erotic Scene (16th century; majolica; Paris, Grand Palais) |

|

| Workshop of Horace Pompeii, Plate with Allegorical Subject (c. 1520-1540; majolica, diameter 23.5 cm; Washington, Corcoran Gallery of Art) |

Ultimately, what could be the significance of Francesco Urbini’s “head of cocks”? We do not know for sure, but it is almost certain that it is a prank, perhaps towards a woman, as would be suggested by the fact that the artist took up in a fiercely sarcastic key a type of female portrait that was very common in Marche pottery of the time. Or towards a Jew, as might be understood by reading the phrase found under the foot, together with the fact that the writing reads from right to left, exactly as in Hebrew writing, and the fact that some of the “cocks” in the composition are circumcised (although the vast majority appear to have simply uncovered glans). But this way of writing could simply be interpreted as a mockery of scholarly circles: only intellectuals who had studied were able to read Hebrew, and consequently the right-to-left writing could simply mock some scholarly (or the whole circles).

It is also not to be ruled out (indeed: it is definitely more likely than the hypothesis of mocking a lady or a Jew) that this object is to be traced precisely to the intellectual circles of the Renaissance courts, where, as we have seen, the eventuality of giving oneself over to “lascivious” thoughts was far from remote, and where, not infrequently, banquets were held where all sorts of officialdom were abandoned, where everything but serious matters were discussed (an image that therefore clashes with that which we might have of the great literati of the past, but is certainly more truthful), where much laughter was had and where bawdy and vulgar verses were declaimed. It may therefore not be so far-fetched to speculate that this pottery, purchased by the Ashmolean Museum in 2003 on the antiquities market (we do not know its original provenance), in ancient times displayed on these occasions. A playful dish used in playful contexts, in short. And all the more valuable when we consider that works such as these were not intended to have a long life.

Essential bibliography

- Barbara Furlotti, Guido Rebecchini, Linda Wolk-Simon, Giulio Romano. Art and Desire, exhibition catalog (Mantua, Palazzo Te, October 6, 2019 to January 6, 2020), Electa, 2019

- Anna Bisceglia, Matteo Ceriana, Paolo Procaccioli, Pietro Aretino and Art in the Renaissance, exhibition catalog (Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, Aula Magliabechiana, from November 27, 2019 to March 1, 2020), Giunti, 2019

- Andrea Bayer (ed.), Art and Love in Renaissance Italy, exhibition catalog (New York, Metropolitan Museum, November 11, 2008 to February 16, 2009 and Fort Worth, Kimbell Art Museum, March 15 to June 14, 2009), Metropolitan Museum, 2008

- Timothy Wilson, An “entanglement” between Leonardo and Arcimboldo. Sexual Iconographies in Renaissance Ceramics in CeramicAntica, XV (2005), pp. 10-44

- Jurgis Baltrušaitis, Maurizio Calvesi, Ester Coen (eds.), Arcimboldi and the art of wonders, Giunti, 1987

- Giacomo Berra, The tradition of “figured alphabets” and the “compound” and “squiggly” heads of Giuseppe Arcimboldo in Tactile Values, 2 (2013), pp. 44-87

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.