The most apt knight and baron. Nicolò da Correggio master of delights in Schifanoia.

While the magnificent exhibition Rinascimento a Ferrara. Ercole de’ Roberti and Lorenzo Costa - and there shine masterpieces of the highest rank in the context of the golden age of Italian humanism - it will not be inappropriate to grasp the personality of a particular protagonist of the life of the northern courts. A figure who was not exactly minor if we decrypt documents, if we evaluate his works, and if we consider his receipt of esteem and familiarity with the lofty names of the nobility and arts of his time, Leonardo included.

We are talking about Count Nicolò II da Correggio (1450 - 1508), who was a poet and dramatist of merit, and moreover capable of translating the figurative inventions of his incessant inner theater into dazzling realities of festivals, balls, carnivals, tournaments; and into symbologies of hunts and banquets. Endowed with a well-established classical and mythological culture, he was capable of scattering creations that were sometimes ephemeral but necessary to the social life of his time: for this he was continually sought after and welcomed by rulers, intellectuals and artists. His emblematic, and certain, portrayal is as the creator and director of the “Month of April” in Schifanoia. Let us see a chronological and related profile of him.

He was born in Correggio, a comital court of the Empire whose titular family already played a role in the political events of the Po Valley Middle Ages, but also a respectable cultural presence with which Azzo da Correggio kept Francesco Petrarch as a guest for three years, receiving his highest friendship for life, and where Count Galasso published the Historie Angliae (the Chivalric History of England) offering it to Filippo Maria Visconti in 1444. A court that was already linked through very definite marriages with almost all the noble families of northern Italy and was about to become related to none other than the Princes of Brandenburg, in the manner of the Gonzaga of Mantua.

The poet wrote the extensive moral work from 1354 to 1360 benefiting from the great hospitality of Azzo da Correggio, who kept him in the peace of Selvapiana, that is, in his hillside estates not far from Canossa

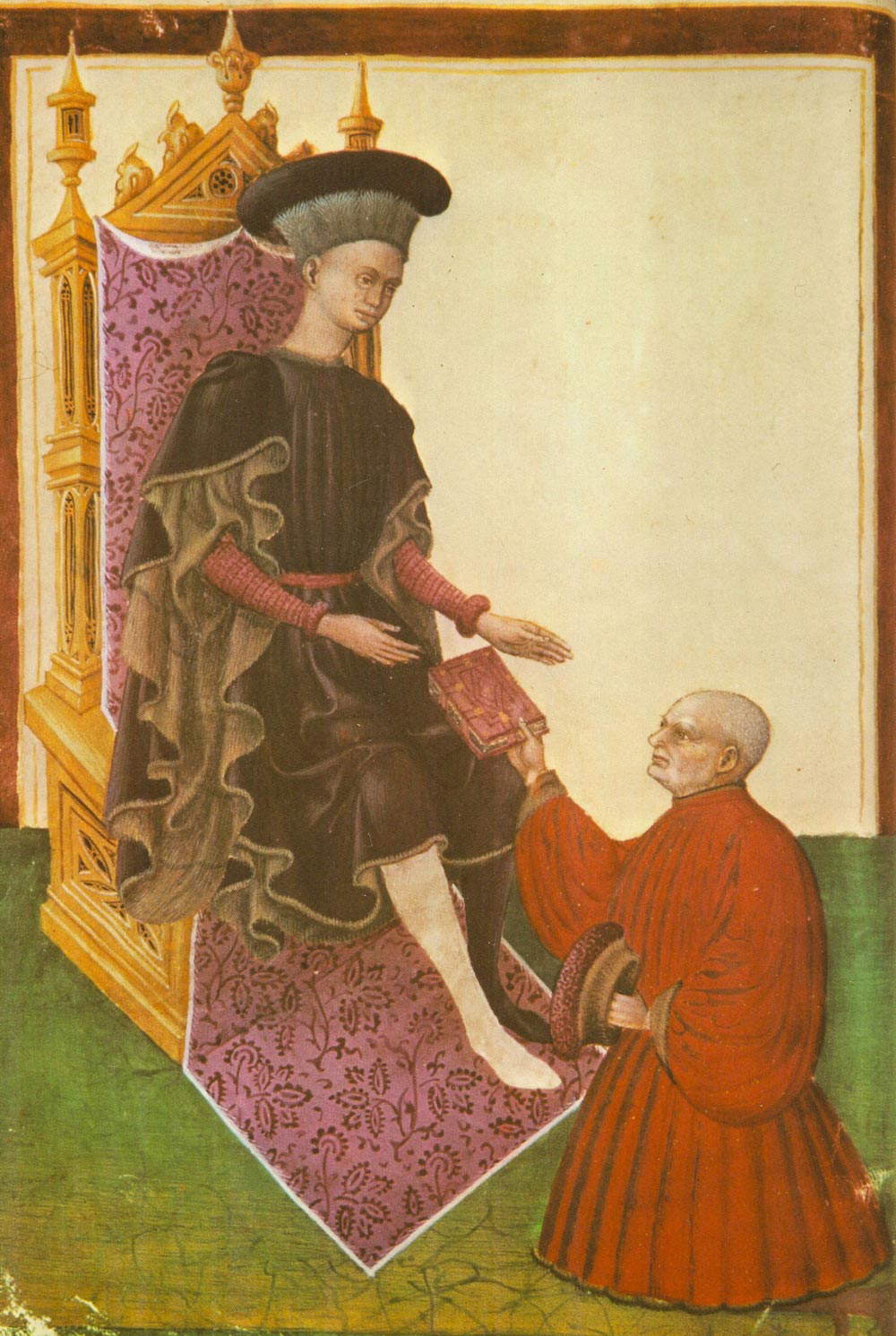

The solemn illuminated image is attributed to Giovanni Zenoni da Vaprio (National Library of Paris ms. lat. 6041 D)

Nicolò I, lord of Correggio, was married to Beatrice d’Este, daughter of the prestigious Niccolò III d’Este, most extensive marquis of the lands of Ferrara and count of Rovigo; but this union, as soon as it took place, met with the misfortune of his death; a death that anticipated the birth of his first-born child: this was 1450. His mother, who had the right of withdrawal of the dowry, took the infant to Ferrara where he, retaining the title and rights of Count of Correggio, grew up and was educated together with his cousin Ercole I (who was to become duke) and was joined by Borso’s extroverted spirit, lover of pomp, festive life and glittering appearances.

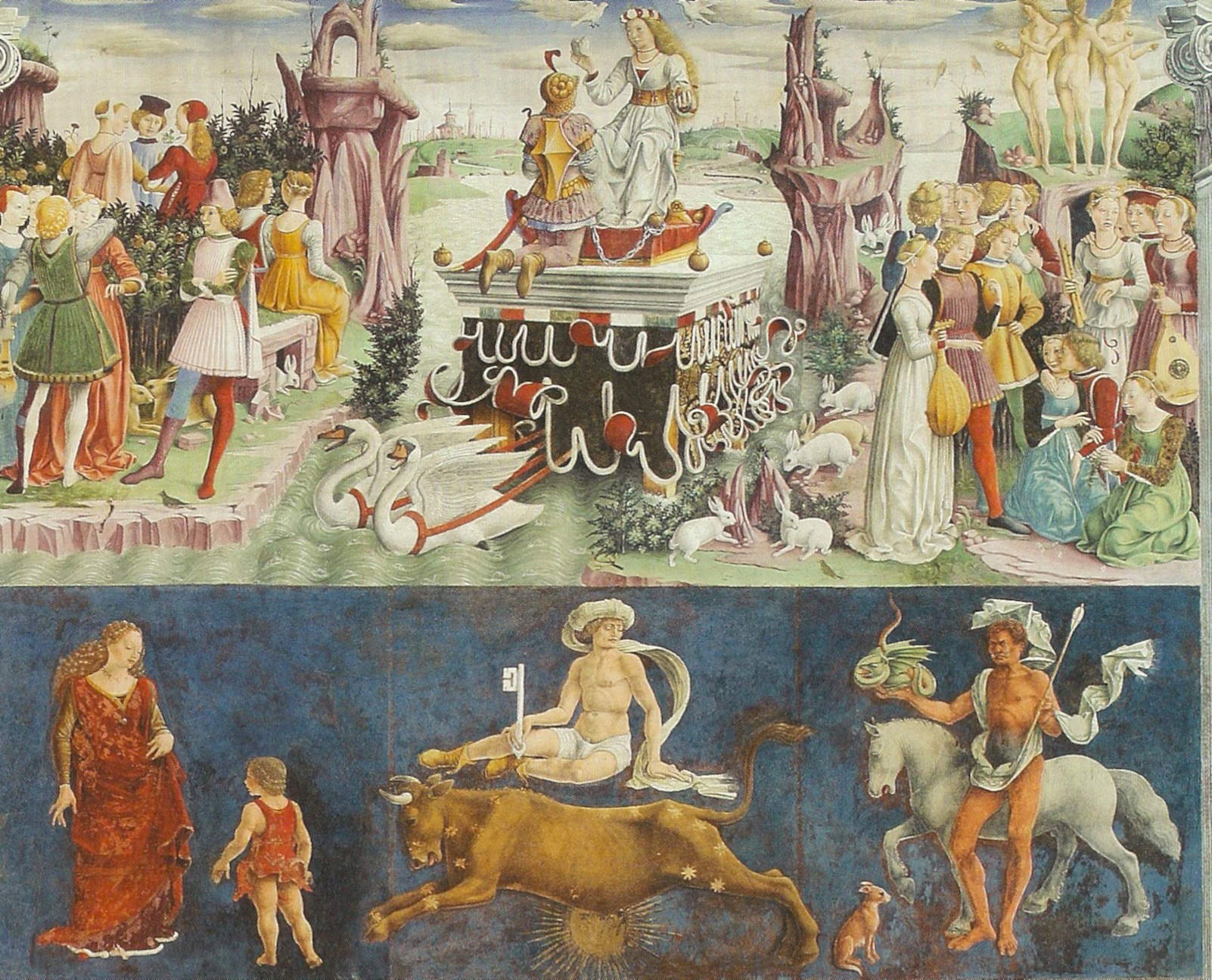

Nicholas II’s courtly education was thorough and intense: along with arms, history, letters, the arts, and the new customs of the nobility were assimilated with enthusiasm; at the age of twelve he obtained the right of the falcon in hunting parties, and in the meantime he related to Pellegrino Prisciani, Guarino Veronese, and his other cousin and peer Matteo Maria Boiardo, who admired him greatly and called him “a gentle spirit and of crowning virtue.” The young count thus began-with vivid genius-to charm the ladies and quant’altro gravitated around the Estense castle. It is a supportable opinion that the idea of making a Salone of unusual size in Schifanoia originated with the Count of Correggio as Master of Dances, in order to obtain the beautiful space of the meetings of couples, quadrilles and teams in the rhythmic cross dances, which from time to time brought the ladies and knights - always interchanged - under the various zodiac signs, gathering intriguing predictions. The Salone di Schifanoia was in essence the first of the kind of unified space environment that other courts would later want to have for music and call “the Hall.” Here in Ferrara, Prisciani thus had the wonderful ease of laying out the serial metaphors of the Months and Decans, painted with ardor by the masters of the court, which were matched by the happy events and the various virtues or fortunes of Borso d’Este: as we still largely observe today.

A consultancy that we might call “transporting,” between Prisciani’s imaginative texts and the mantic figurations of the fascinating mural megalography, was certainly given by Count Nicolò with his theatrical vocation, his brooding culture pregnant with mythological allegorism, his sprinkling chromatic taste, and with the conjunctive ability between parietal patterns and dancing movements that only a director of genius could possess and convey.

The reason for this certainty of ours has a simple answer: let us ask ourselves who in the most dazzling month, the Month of April, arranged it all and now leads the grand celebration? It is he, Nicolo da Correggio! You see him with folded arms watching the lovers and observing the order of the whole symbolic magnificence of “his” month of loves. All this takes place just before 1470 by the admirable hand of Francesco del Cossa. A historical proof lies in the fact that in 1472 the Count of Correggio married Cassandra Colleoni, one of the daughters of the famous condottiere, and it is no coincidence that the great Bartolomeo “dalle tre possanze” receiving in 1474 King Christian of Denmark on behalf of Venice succeeded in realizing that contrived series of banquets, balls and tournaments that have remained famous in the history of the Serenissima, and that required a truly talented director.

On the high podium we witness the “Triumph of Venus,” Lady of the sign of Aries, where candid swans move the river chariot that proceeds through the lands reclaimed by the Este family; some rocks in the form of theatrical periaktoi offer planes and shelters. The Goddess holds an apple and a flower, and before her kneels Mars, the god of war, cataphracted in splendid armor but chained by love: he portrays the legendary Lohengrin, the Swan Knight. On the left Nicolo observes the pre-arranged couplings of the lovers; on the right the young men and maidens prepare for music - mistress of eros - with some somewhat hidden daring. Above, the three naked Graces exchange significant apples, and the animals (rabbits, pigeons, and finches) leave no doubt about the predictions of fecundity. Prominent among the decans is the one in the center, above Aries (zodiac sign of the period) where an almost naked male is stretched out flaunting the key: a paradigmatic emblem of intercourse in popular Po Valley slang. The side decans, on the other hand, mark the two erotic extremes: the violent and the sweetest extremes of the fulfillment of love

On the other hand, in order not to slip into a historical excursus, it will suffice here to recall some actions that linked our Nicolò to the pulse of the Renaissance. As a scholar of ancient literature and mythology he came to recreate the Italian theater with the famous performance of the “Fabula de Cefalo” held on January 21, 1487 (carnival period) in the courtyard of the Castle of Ferrara, where the acting of the costumed characters on the stage, the division into acts, the interludes of the chorus of nymphs, and the use of pictorial backdrops first occurred. Chronicles say that after the tragic ending of Procri’s death all the ladies wept; then the bold author took the stage and announced that the goddess Diana had granted the bringing back to life of the maiden beloved by Cephalus, and had the new ending performed with resounding success. Such things happened in the court of Hercules I, who wanted to dine in the chambers while his painter de’ Roberti frescoed the instories of Cupid and Psyche, at Belriguardo!

Because of his talents, the Count of Correggio was in demand by other Renaissance courts. With the approval of the Duke’s cousin he was often in Milan to organize the receptions and processions of the “two carnivals” (the Christian and the Ambrosian, he said); he was director and costume designer to Leonardo, by whom he was highly esteemed and of whom he became a friend: to the Tuscan genius, who sometimes boggled at a beautiful face, he dedicated a playful sonnet. He got valuable drawings of it in return, we do not know whether in originals or copies, but he took them with him for the careful emblematic drafting he intended to do in his palaces in Correggio. Meanwhile, Ercole d’Este insistently called on him for his own parties and for certain diplomatic representations. Nicolò traveled to Italy and France; Ercole I sent him to Paris to look after the education of his son Alfonso, and from there he described the admirable “courtesies” of royal ceremonies around Charles VIII.

The verses seem to allude to a female portrait Leonardo was painting in Milan around 1490. The tone is confidential and jocular, so much so that it touches on the great genius’ amusements and gives him somewhat vexatious advice

Our Lord had found time to take part in the “Polesine War” between Ferrara and Venice (1482-1484) where he was taken prisoner by the Venetians; but then it was above all in the Ferrara environment that he experienced that temperament of new architecture and town planning that made him a friend of Biagio Rossetti, helping him find materials for his little house in Via della Ghiara. Rossetti, during his presence in the ducal lands of Reggio, reciprocated with a probable passage from Correggio, where he left the project for the new palace of representation of the local lords and where he gave the scheme for the extension of the Borgo Nuovo, in which the admirable meters of the Herculean Addition are still experienced today.

The imprint of Biagio Rossetti is obvious and splendid. The masonry workers and especially the high-class marble workers also came from Ferrara bringing Istrian stone for the Portal and other stone materials for columns, cantonaria and capitals. (Photo Giancarlo Garuti)

This is one of the heraldic-mythological inventions that Leonardo had proposed in Milan for the costumes of the “Festa del Paradiso” (1490) and other carnivals. Nicolò took these designs and applied some of them in the beautiful Portal of the new family palace

As a special member of the d’Este family, the Count of Correggio was always welcomed and revered in the life of the Ferrara court; on the occasion of the inter-parental conspiracy of 1505 he acted as the ultimate peacemaker for the benefit of ducal continuity, and Alfonso I assigned him the splendid Palazzo di Giulio, enlivened by the most beautiful urban garden in Ferrara: it is the present Palace of the Prefecture of the city.

Staying with our subject, we must remember Nicolò’s very close relationship with his cousin Isabella d’Este Gonzaga, who admired him exceedingly and called him insistently to Mantua. For her he designed a famous knot dress and gave advice of courtly character to no end; to her he introduced young Correggio to be admitted to Mantegna’s studio, and for her he organized shows and tournaments of arms. In Nicolò’s very dense correspondence with Italian nobles, including Lorenzo the Magnificent, the letters with Isabella stand out: among them a moving hyperbole is the one where the Nostro, now in his fifties, congratulates himself on the birth of a little girl at the Gonzaga court and says “I would like to wait for her to dance with her in the Sala.” Shortly after his death Isabella with great regret remembered him as “the most atilated et de rime et cortesie erudito cavaliere e barone che ne li tempi suoi se ritrovasse in Italia.”

Bibliographical note: On the life, relations with princes and men of letters, poetic and theatrical production, organization of festivals and tournaments, of Our protagonist see “Nicolò da Correggio and court culture in the Po Valley Renaissance,” edited by Antonia Tissoni Benvenuti. Cassa di Risparmio di Reggio Emilia, 1989. Also other publications by the same editor.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.