At 10:17 p.m., Italian time, on July 20, 1969, U.S. astronaut Neil Armstrong, leading the Apollo 11 mission (the spacecraft’s crew was completed by Edwin Aldrin and Michael Collins), began his walk on the moon. For the first time in history, man set foot on our satellite.To celebrate, exactly fifty years later, the important anniversary, we have come up with a gallery of works that feature the very moon that by artists was conquered long before by astronauts!

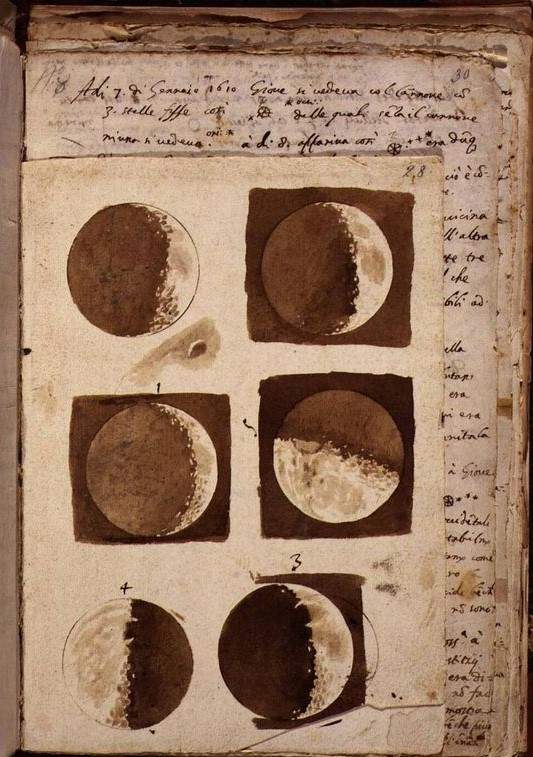

1. Galileo Galilei, Astronomy. Observations of Lunar Phases, November-December 1609 (1609; autograph paper manuscript, watercolor drawings on paper, 33 x 23 x 1.7 cm; Florence, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Galileiano 48

We begin the review with a sheet that is not really a work of art, since it accommodates the drawings of the phases of the moon drawn by Galileo Galilei (Pisa, 1564 - Arcetri, 1642) during his astronomical observations in the autumn of 1609: nevertheless, it is the first graphic record of the moon as we know it today (with its craters, its seas, its depressions). Before Galileo discovered that the moon had a rough and irregular surface, the common belief, fueled by religion, was that the moon was a perfect body. In addition, Galileo also had a great passion for art, and he was friends with one of the greatest artists of the time, Ludovico Cardi known as the Cigoli, a Tuscan like himself. And the great Pisan scientist, in offering us the first realistic depiction of the moon, demonstrated an expert draftsman’s hand: after all, knowing how to draw was almost a prerequisite at the time for being an excellent scientist.

|

| Galileo Galilei, Astronomy. Observations of the Phases of the Moon, November-December 1609 |

2. Adam Elsheimer, Escape to Egypt (1609; oil on copper, 31 x 41 cm; Munich, Alte Pinakothek)

In this painting by the German painter Adam Elsheimer (Frankfurt am Main, 1578 - Rome, 1610), the role of the episode, the flight to Egypt, takes on almost a marginal role: in fact, the work has passed into art history not so much for its religious content as for its ... celestial content. Indeed, we see that, in this admirable nocturne, Elsheimer depicted a cascade of stars that take on the appearance of the Milky Way: it has been hypothesized by some scholars (including Anna Ottani Cavina) that the Frankfurt-based artist was somehow familiar with Galileo Galilei’s studies on the subject, although it must be remembered that Sidereus nuncius, the astronomical treatise in which the surface of the moon is also discussed, had been published in 1610 (but it is not excluded that Elsheimer retouched the work in that very year). But Elsheimer’s sky could also be the result of direct observations of the stars, then reworked in an “artistic” key, since there are several inconsistencies, starting with the great protagonist, the moon: if in reality the sky were so cloudy, the stars (at least the nearby ones) would hardly be seen. However, the moon is the great protagonist of the work, and it illuminates the pond in which it is mirrored (although its reflection seems a little unrealistic, however suggestive).

|

| Adam Elsheimer, Escape to Egypt |

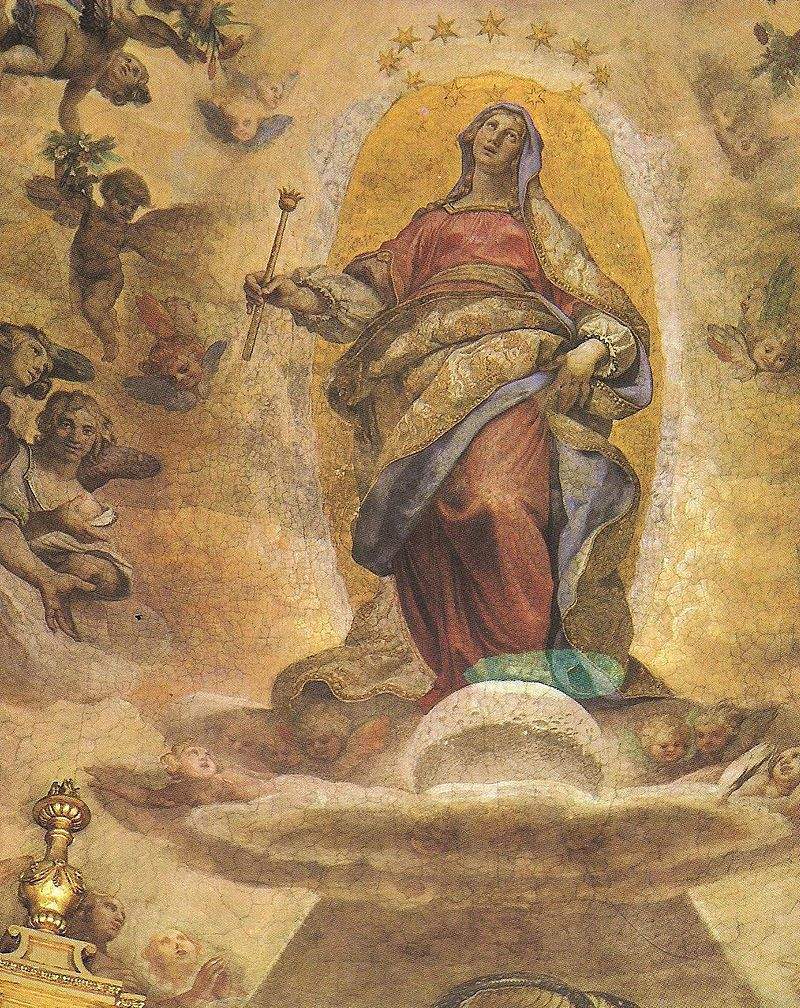

3. Ludovico Cardi called the Cigoli, Assumption of the Virgin or Immaculate Conception (1610-1612; fresco; Rome, Santa Maggiore, Pauline Chapel)

As mentioned above, Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli (Cigoli di San Miniato, 1559 - Rome, 1613), almost Galileo’s contemporary, was a great friend of the scientist, and just as the latter was passionate about art, Cigoli was passionate about astronomy. And it was precisely because of his friendship with Galileo that the artist from San Miniato left us the first realistic depiction of the moon in a work of art: this is the fresco with the Madonna (alternately interpreted as an Assumption of the Virgin or as an Immaculate Conception) commissioned by Pope Paul V for the Pauline Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome. The Church at the time thought of the moon as a pure, smooth, perfect body without roughness. Yet Cigoli was not censured: the ecclesiastical authorities preferred to remain cautious. We have discussed this work and this affair in detail in an article that you can find at this link.

|

| Ludovico Cardi known as Cigoli, Assumption of the Virgin or Immaculate Conception. |

4. Guercino, Endymion (1647; oil on canvas, 125 x 105 cm; Rome, Galleria Doria Pamphilj)

According to Greek mythology (or at least, according to the most popular version of the myth), Endymion was a young, beautiful shepherd with whom Selene, the goddess of the moon, fell madly in love. Selene was enamored of him to the point that she asked Zeus for the possibility of giving him eternal youth and a state of eternal sleep, so that the goddess could go to him forever.Selene was in fact tormented by the idea that Endymion’s mortal status might sooner or later deprive her of him. There are many artists who have tried their hand at depicting the myth, and one of the most beautiful interpretations is that provided by Guercino (Giovanni Francesco Barbieri; Cento, 1591 - Bologna, 1666) who, as per typical iconography, depicted Endymion slumbering, with the moon (which we see in the sky) watching over him. There is a very interesting detail in this work: the presence of the spyglass resting on the young man’s knees, a spyglass that has the shape and size of “Galilean” ones. According to a recent interpretation by scholar Pierluigi Carofano, the work could be of Medici commission and could take the form of an attempt by the Medici to rehabilitate the scientist’s memory after ecclesiastical censure. Curiously, according to some ancient versions of the myth, Endymion would have been an astronomer himself. Whatever the significance of the presence of the telescope, Guercino’s is, in any case, an image that well restores us to the climate of the time, since in Medici Florence, especially after Galileo’s death, interest in his studies and discoveries was strong.

|

| Guercino, Endymion |

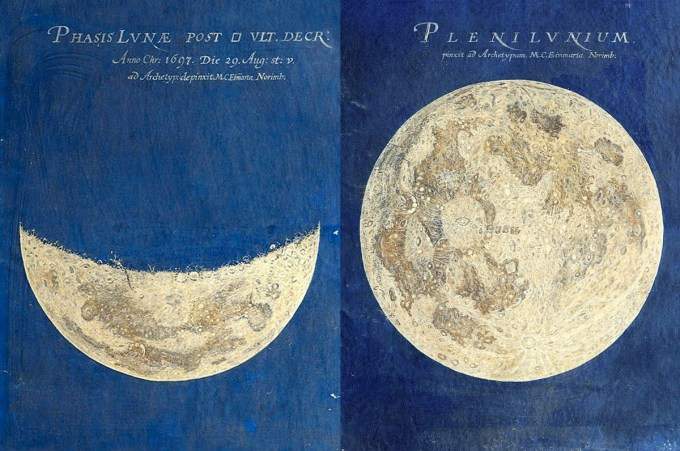

5. Maria Clara Eimmart, Lunar Phases (late 17th century; pastel on blue cardboard, 64 x 52 cm; Bologna, University of Bologna, Museo della Specola)

Maria Clara Eimmart (Nuremberg, 1676 - 1707) was one of the first female astronomers in history and, like Galileo, was an excellent draughtsman, not least because she was a child of art: her father Georg Christoph was in fact a painter (he was moreover director of the Nuremberg Academy of Fine Arts in the early eighteenth century), and he also dabbled in astronomy. The unfortunate young woman (she died in childbirth at the age of only thirty-one, just a year after marrying mathematics professor Johann Heinrich Müller) demonstrated her great talent, both as an astronomer and as a draughtsman, in a series of plates made in pastel, some of which are now preserved in the Specola Museum in Bologna. These drawings were born after careful observations at the telescope and were gathered by Maria Clara into a series that was entitled Micrographia stellarum phases lunae ultra 300 (“More than 300 micrographs of the stars and phases of the moon”). The Bolognese plates were given to Luigi Ferdinando Marsili (Bologna, 1658 - 1730), a great scientist and friend of Georg Christoph, who brought them to Emilia. Many others, however, were lost, mostly due to a fire that devastated the college library where the manuscript that included several of his plates (which were kept by her husband after her disappearance). Those that survive, however, are surprising in their great accuracy and are further evidence of the great development that astronomy experienced between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

|

| Maria Clara Eimmart, Lunar Phases |

6. Donato Creti, Astronomical Observations. Moon (1711; oil on canvas, 51 x 35 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums)

The aforementioned Luigi Ferdinando Marsili, it may have been guessed, although he was mainly active in the field of natural sciences, had strong interests in astronomy. Thus, in 1711, he commissioned one of the greatest painters of the time, Donato Creti (Cremona, 1671 - Bologna, 1749), to paint a series of oil paintings on canvas: each of them was to depict astronomical observations of a different celestial body. The moon, of course, could not be absent, and Creti provided a most faithful depiction of it: a presence looming powerfully over the two astronomers who, in the glow of a clear night, observe it with their telescope. The size of the moon may not be true, but it matters little: Marsili’s purpose was to convince the ecclesiastical authorities of the need to study the stars. For this, the Bolognese nobleman, well-connected in Roman circles (Bologna was part of the Papal States, and then Marsili a sort of war hero: before devoting himself to science he fought against the Turks, was even captured, and later held diplomatic positions on behalf of the Empire), made a gift of it to Pope Clement XI. A gift that perhaps had to prove convincing, since, at the behest of the Bolognese Senate, between 1712 and 1726 the Torre della Specola was built at Palazzo Poggi, built precisely with the intention of making it an astronomical observatory (it was the first public observatory in Italy). Marsili thus saw his dream crowned, and we like to think that art played no small part in this affair.

|

| Donato Creti, Astronomical Observations. Moon |

7. Canaletto, The Eve of Santa Marta (ca. 1760; oil on canvas, 119 x 187 cm; Berlin, Gemäldgalerie)

In the production of Giovanni Antonio Canal, known as Canaletto (Venice, 1697 - 1768), there is no shortage of splendid and precise moonlit nocturnes: the artist loved to paint his Venice at night on the occasion of festivals. These included the eve of Santa Marta, a celebration of the saint accompanied by a popular feast. The saint was patron saint of the city’s neighborhood of the same name, and on July 29, at the height of summer, she was celebrated with a very popular festival. In the moonlight, Venetians thus throng the shores, lit for the occasion with artificial lights, with stalls and tents set up for the festival, while some boats ply the sea. It is all dark, but the full moon, with its glow, illuminates the sea and the outlines of the figurines that line the city’s shores.

|

| Canaletto, The Eve of Santa Marta |

8. Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon (1819-1820; oil on canvas, 20.35 x 44.5 cm; Dresden, Galerie Neue Meister)

The Two Men Contemplating the Moon is one of the most representative Romantic landscapes in the art of Caspar David Friedrich (Greifswald, 1774 - Dresden, 1840), where the satellite is often the great protagonist, with moonlit views of lonely seas, or with figures who, as in this case, wander into dense bush and then stop to admire it. In this painting preserved in Dresden, the lunce and conformation of the sky suggest that in fact the night is ending and dawn is approaching. A sense of disquiet and melancholy, heightened by the bare branches of the trees and the arid rocks, envelops the entire composition: mystical-spiritual tension, awareness of the fact that man is tiny compared to the cosmos, fright and at the same time an attraction to the power of nature (typical of the aesthetics of the sublime) are some of the elements inferred from this landscape, of which Friedrich later made other versions (one of which features a couple formed by a man and a woman). We do not know who the two men are absorbed in contemplation of the moon: however, it is likely that one of the two is Friedrich himself. A political interpretation of the work has also been given, ironically suggested by Friedrich himself: when the poet Karl Förster visited the artist in 1820 and observed the work, the painter told him that the two figures “are plotting some demagogic intrigue.” Germany was living, at that time, a very troubled time, and in the same 1819 the so-called Karlsbad Deliberations were issued, a series of decrees that introduced surveillance measures on the activities of universities and the press, all to suppress any liberal dissent in the Germanic Confederation established following the Congress of Vienna. Measures that were much criticized by intellectuals of the time (and perhaps also in this painting by Friedrich).

|

| Caspar David Friedrich, Two Men Contemplating the Moon. |

9. Salvatore Fergola, Nocturne on Capri (c. 1843; oil on canvas, 106 �? 131 cm; Naples, Museo e Real Bosco di Capodimonte)

One of the most beautiful nocturnes of Italian Romanticism, Notturno a Capri by Salvatore Fergola (Naples, 1799 - 1874) depicts a view of the Gulf of Naples in front of the Marina piccola, against the backdrop of the Faraglioni, as sung in popular Neapolitan songs, with the sea on which “the silver star shimmers,” the moon illuminating the sky and the boats of Capri fishermen moored a short distance from the shore with their sails still raised to dry. The work is now kept at the National Museum of Capodimonte, where it arrived in 1967 as an inheritance from the collection of Nicola Santangelo, who was minister of the interior under King Ferdinand II of Bourbon: Santangelo had a strong fondness for Fergola’s nocturnes. Fergola’s nocturnes were the first produced by the Neapolitan Romantic school: the artist had been inspired by the French painting counterparts that were fashionable at the time and was the first to spread the taste for this type of view in the Neapolitan area.

|

| Salvatore Fergola, Nocturne on Capri. |

10. Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night (1889; oil on canvas, 72 x 92 cm; New York, Museum of Modern Art)

The Starry Night(De sterrennacht in Dutch) is one of Vincent van Gogh’s (Zundert, 1853 - Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890) most iconic works, as well as one of the most representative of the latter part of his career.The painting dates from 1889, in fact, and was made in Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, where he was at the time admitted to a psychiatric clinic. It was during that stay that van Gogh’s art experienced a turning point that led him to a style that was more “expressionist” than “impressionist,” and the canvas soon became the site on which the Zundert artist depicted landscapes as he saw them within himself, a response of his imagination to nature. “This morning,” Vincent wrote in a letter to his brother Theo on June 6, 1889, “I looked at the countryside from my window long before the sun came up, with nothing but the morning star, which looked really big. Daubigny and Rousseau have already painted this subject, expressing all the intimacy, peace and majesty and adding such a strong feeling and so personal. I do not regret these emotions. I still feel enormously remorseful when I think of my work, so little in harmony with the way I would like it. I hope that in the long run I will succeed in doing better things, but right now we are not there yet.” Van Gogh thus created his landscape with dense, mellow brushstrokes, depicting a landscape that is partly real, but partly invented (the church with the tall spire evokes the houses of worship in the Dutch countryside where the artist grew up). It is thus not a real landscape, rather an inner vision of the artist, a kind of dream that makes manifest the painter’s emotions at the time.

|

| Vincent van Gogh, Starry Night |

11. Osvaldo Licini, Amalassunta on a Blue Background (1951; oil on canvas, 25.5 x 34 cm; Private collection)

The great painter Osvaldo Licini (Monte Vidon Corrado, 1894 - 1958) felt a strong bond with the moon, which he called “Amalassunta”: in a letter to the critic Giuseppe Marchiori, dated May 21, 1950, Licini wrote that Amalassunta is “our beautiful moon, guaranteed dargento per leternità, personified in a few words, the friend of every slightly weary heart.” The moon becomes an object of serene contemplation, often surreal, capable of giving rise to extraordinary dreamlike visions where the satellite takes on a human face and from time to time interacts with the characters Licini brings to life. We do not know for sure why Licini had decided to call the moon “Amalassunta.” in an interview given on the occasion of the 1958 Venice Biennale, the painter said he was fascinated by the name of a princess from Ravenna, Amalasunta, who lived between the fifth and sixth centuries A.D. Recently Lorenzo Licini, the artist’s nephew, has associated the name “Amalassunta” with two anagrams (“the holy muse” and “Malus, Satan”), bringing the artist’s works closer to the poems of Baudelaire, of whom he was very fond.

|

| Osvaldo Licini, Amalassunta on a blue background. |

12. Giulio Turcato, Lunar Surface (1968; oil and mixed media on foam rubber, diameter 90 cm; private collection)

Among the Italian artists of the 1960s, one of the most sensitive to the theme of lunar travel was Giulio Turcato (Mantua, 1912 - Rome, 1995), who dedicated an entire strand of his production, that of Lunar Surfaces, to the moon. The great artist’s intent was to construct the image of the moon through everyday materials, particularly foam rubber. The conquest of space and the race to the moon thus became concrete matter in Turcato’s art, which looked optimistically at the technological and scientific advances of those years. “I use rubber,” Turcato himself declared in 1971, “because its rough crust is full of new warnings and wonder.” And indeed, acting on the foam rubber, Turcato recreates the surface of the moon with surprising verisimilitude.

|

| Giulio Turcato, Lunar Surface |

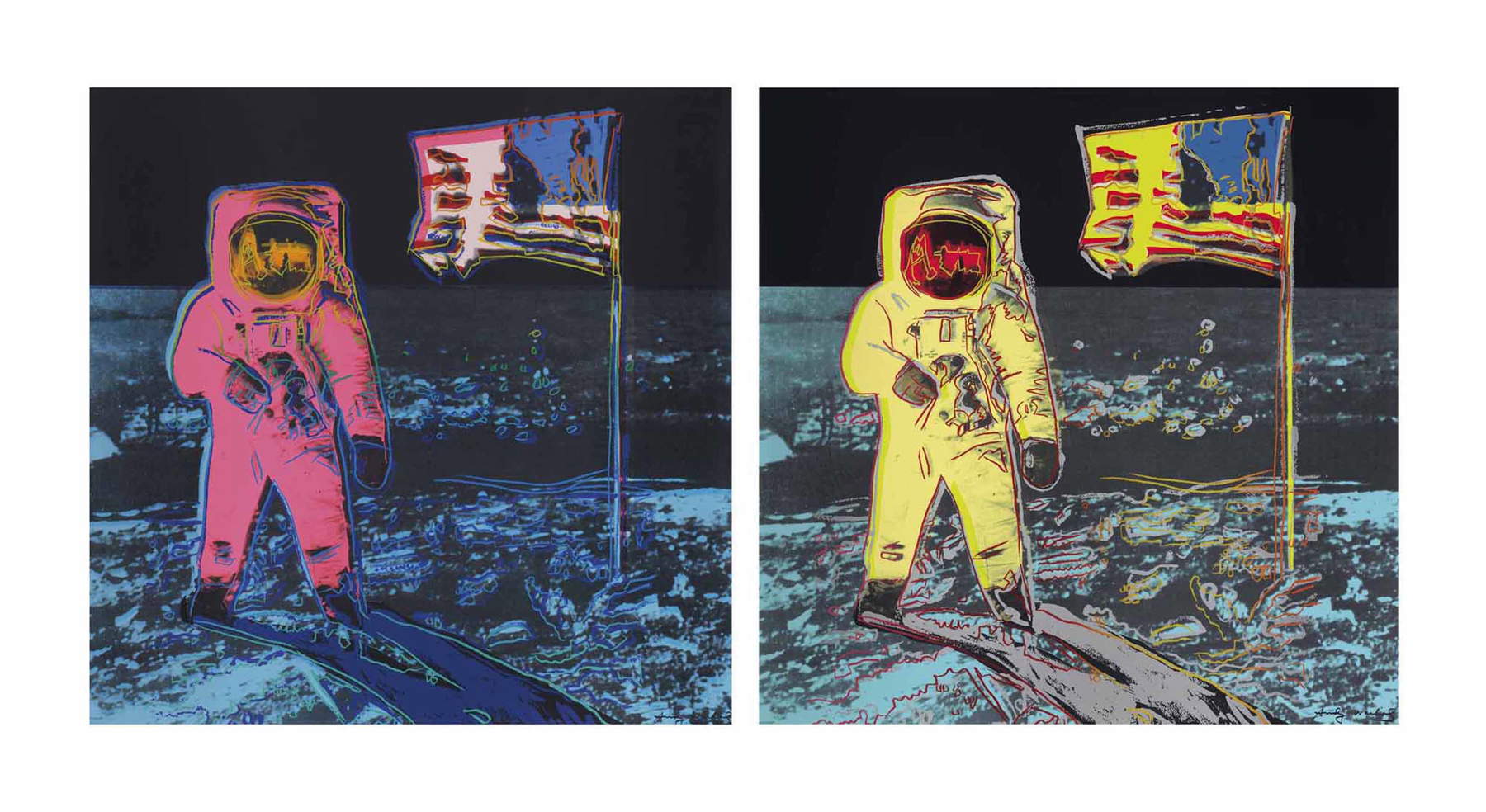

13. Andy Warhol, Moonwalk (1980s; silkscreen; various locations)

As an important witness of his time, Andy Warhol (Pittsburgh, 1928 - New York, 1987) could not fail to pay tribute to Neil Armstrong setting foot on the moon for the first time. Thus, the celebrated photograph depicting the American astronaut next to the flag of the United States also became an icon of pop art. Certainly not among the best known, but present nonetheless.

|

| Andy Warhol, Moonwalk |

14. Anish Kapoor, Moon Mirror (2014; stainless steel and lacquer, diameter 114 cm; Private collection)

Among contemporary artists, Anish Kapoor (Bombay, 1954) is among those most interested in astronomy themes, and there are several of his works on the subject. He is also a great admirer of Galileo: and the scientist would seem to be twice paid homage to in Moon Mirror, a successful strand of Kapoor’s production. The shape and lacquer inserts recall the celestial body, while the mirror is an homage to the instruments astronomers use to observe the satellite (and the stars in general).

|

| Anish Kapoor, Moon Mirror. Courtesy Massimo Minini Gallery |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.