In the center of the Perugino room in the National Gallery of Umbria is a particular work by Pietro Vannucci known as Perugino (Città della Pieve, c. 1450 - Fontignano, 1523): it is in fact the Monteripido Altarpiece, an opisthograph altarpiece, that is, awork with two sides. And it is precisely in order to allow the public to admire both sides, front and back, that the altarpiece has been placed in the middle of the room, so that they can walk around it without any hindrance. Although different from each other, both sides of the Monteripido Altarpiece deserve to be observed in detail: on one side is the Crucifixion, on the other theCoronation of the Virgin.

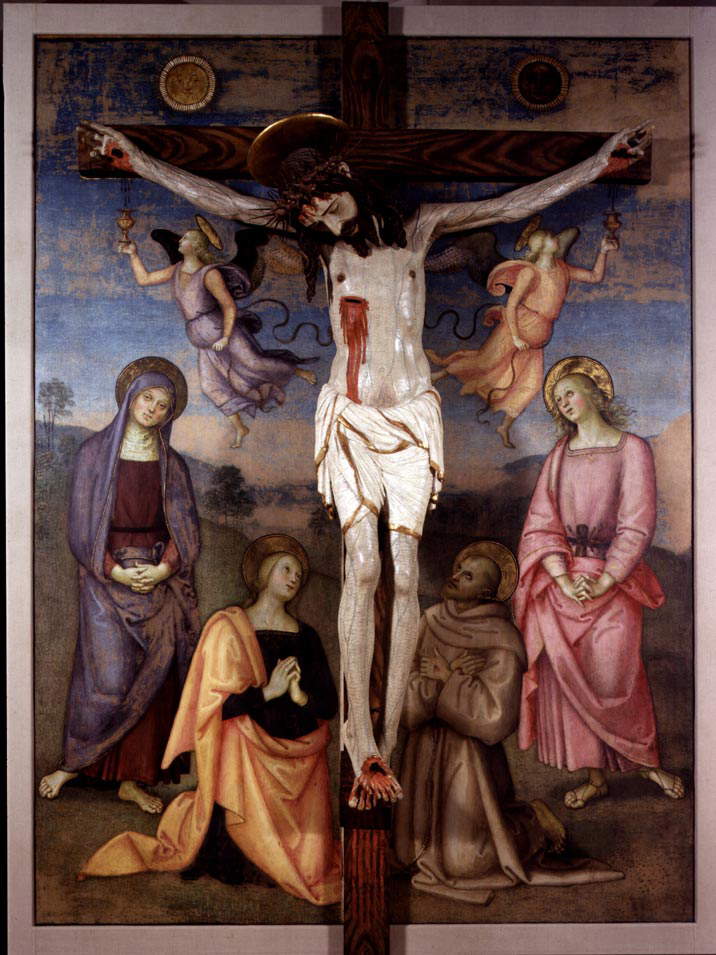

Although it is inevitably the former that fascinates the viewer the most, for here Perugino created a marriage of painting and sculpture, later adding an extremely dramatic wooden crucifix over the painting. The polychrome wooden sculpture was long attributed to a sculptor attested in Perugia from 1541 to 1562, Eusebio di Gianbattista Bastone, but it was Margrit Lisner ’s 1960 contribution devoted to wooden crucifixes of German taste widespread in Italy in the 15th century that gave us the idea of bringing together similar examples: the Crucifix of the Monteripido Altarpiece was being compared by her with the Christ of thePerugian abbey of San Pietro, attributed by documents of 1478 to a “Giovanni todescho,” but the scholar shied away from referring them to the same author. Thus began studies on the production of carvers of German origin active in Italy: Elvio Lunghi confirmed within the corpus of Giovanni Teutonico ’s works the presence of the Monteripido Crucifix, and it was thanks to Sara Cavatorti ’s contribution that the sculptor was identified with “magister Ioannes Arrighi de Salbu[r]gho de Lamania alta,” a resident of Terni, who in February 1495 sold a crucifix to the Franciscans of the same city. The Monteripido crucifix can be dated to between the sixth and seventh decades of the 15th century: Cobianchi linked to the making of the crucifix an act of 1452 through which Tommaso di Paolo de’ Ranieri arranged a legacy in favor of the Monteripido friars for the execution of an altarpiece intended for thehigh altar of their church, and the scholar referred this to the Monteripido Crucifix he dated within the sixth decade of the fifteenth century and actually placed on the high altar of the convent. It would therefore be from an earlier period than the painted altarpiece.

Perugino,

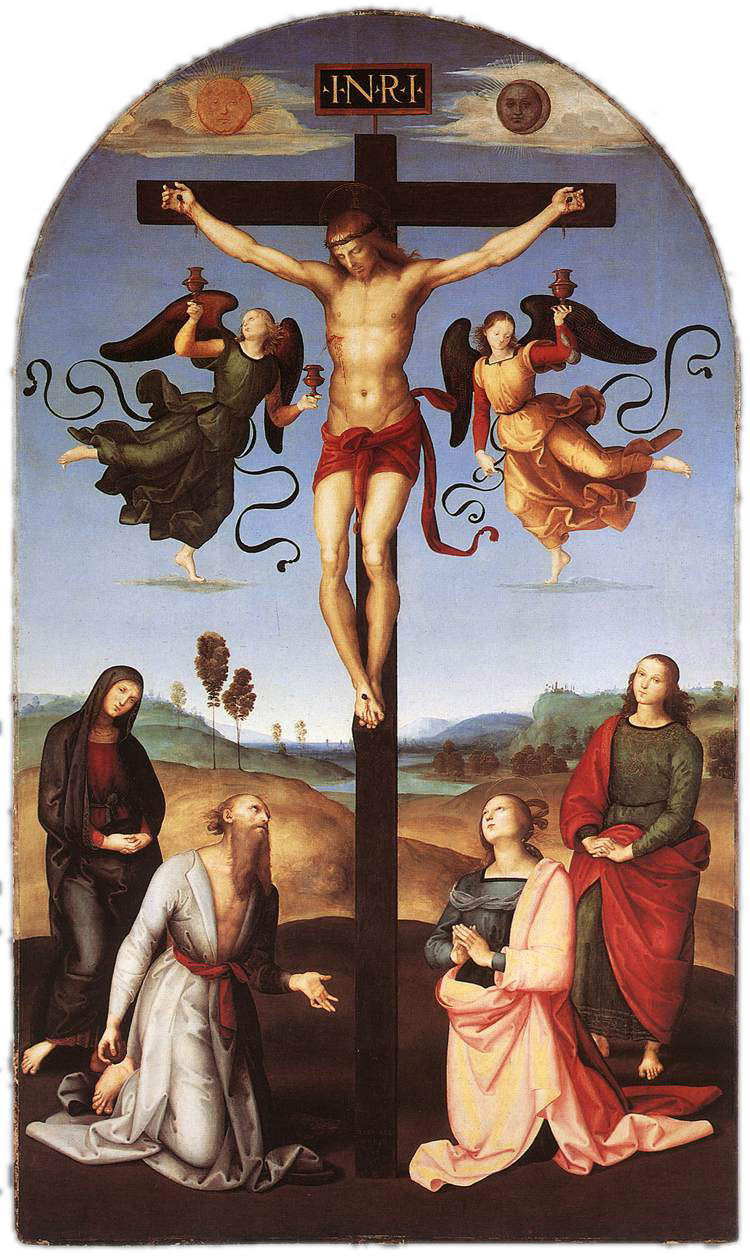

Perugino,

Perugino in fact signed on September 10, 1502, in the church of San Francesco al Monte in Perugia, also known as the Convent of Monteripido to distinguish it from the Perugian church of San Francesco al Prato, the contract for the allocation of the altarpiece destined for the convent’s high altar with Bonaventura di Pietro, a guardian friar representing the community of Franciscan friars who had founded a true center of the Osservanza here. The commission contract indicated in detail to the painter how to proceed in the execution of the work, specifying not only the themes but also the number of the characters to be depicted, their positions, and the decorations of the ancillary parts. For 120 florins the painter undertook to paint on an already existing panel on the church’s high altar four figures (the Madonna, St. John the Evangelist, St. Francis and Mary Magdalene) on either side of a crucifix that also already existed and was already displayed on the high altar in the direction of the choir.

It is very likely, as Veruska Picchiarelli explains, that the side on which the cross was placed had received an abraded ornamentation to allow Perugino to carry out his work, and that the relationship between painting and sculpture was the result of a precise iconographic choice of the patrons. Already previously, the wooden Christ was in fact displayed in the direction of the choir to address the friars themselves, who could thus take a good look at thetortured effigy of Christ and have a clear idea of the suffering to which the Savior was subjected. As noted by Picchiarelli, Giovanni Teutonico could not, however, have imagined that those effects of charged patheticism, with wounds and theatrical artifice (such as the presence of the mobile tongue device and a canal dug into one of the nostrils that may have been used to drip animal blood, discovered by Maria Cristina Tomassetti and Daniele Costantini during the restoration and diagnostic investigations), would be dampened about half a century later “by the forced coexistence with a composition of Arcadian serenity, in which the mourners seem almost impassive in the face of so much pain, absorbed in their own meditations.” Indeed, one notices the contrast between the striking wooden Crucifix and the delicate, quiet painted figures and the gentleness of the surrounding landscape.

The contract also spoke of the other side of the panel, facing, however, the “chiesa de le donne,” or the space accessible to the faithful, and Perugino undertook here to paint aCoronation. Perugino was therefore asked for an altarpiece to be placed on the high altar that would be painted on both sides so that these would be visible from both the nave and the choir in order to address two types of audience: the friars and the faithful. The friars chose subjects , however, that would make that altarpiece a true manifesto of Franciscan Observance: the Crucifixion , which was meant to arouse religious piety and identification with the sufferings of Christ and his Passion through a strong, almost ostentatious and crude patheticism, in the expression of which carvers of German origin were particularly skilled; theCoronation, on the other hand, was part of the friars’ predilection for the Marian cult and the dogma of theImmaculate Conception. “The solid theological framework of Perugino’s opisthographic altarpiece,” writes Veruska Picchiarelli, "should therefore be understood as a reflection of the learned climate that must have breathed in Monteripido, the seat, from 1440, of the Studium generale dell’Osservanza."

As seen now, the altarpiece thus presents on the recto the Crucifixion, set in the gentle hillside landscape; Christ is pale, his head turned downward and encircled by a crown of long thorns, his mouth half-closed, his veins in relief, and blood gushing copiously from the wounds in his hands, feet and side. Kneeling at the foot of the cross are Magdalene and St. Francis, while standing at the sides are Our Lady and St. John the Evangelist. Two angels in flight catch inside chalices the blood falling from the wounds of the hands. In the sky, the Sun and Moon represent the New and Old Testaments. Christ, in the center between the two stars, represents the union between the Jewish and pagan people. The verso, on the other hand, depicts theCoronation of the Virgin built on two levels. In the upper part, inside a mandorla, Christ crowns the Virgin both surrounded by angels holding a single garland of flowers in their hands and by cherubs. Attending the scene, in the lower part of the painting, are the twelve apostles standing observing the gesture with their heads turned upward; except for St. Peter, recognizable by the key he holds in his hands, and three other apostles placed in the background. The landscape is still the hilly one typical of Perugino.

It is likely that the painter made the Monteripido Altarpiece on several occasions, as he was absent from Perugia in late 1502 through the end of 1503, returning to the city occasionally thereafter until at least the summer of 1504. It should also be borne in mind that the commission required a gilded carpentry and a tripartite predella, with a Pieta, the effigies of St. Bernardine of Siena and St. Bernardine of Feltre , and the trigram of Christ, but both the carpentry and the predella have not come down to us, as they were probably destroyed with the requisition of the central panel, lacking the Crucifix, by theNapoleonic army. In fact, the panel was transferred to France in 1797; from Paris it returned to Rome in 1817, and in January 1818 it arrived in Perugia thanks to Marquis Braccio Bracceschi , who advanced the transportation costs. The work remained with the marquis for a long time at least until it was reimbursed, and after returning to its original location it was reunited with the wooden Crucifix in July 1822. Following post-unification demanations it was finally still removed in 1863 to enter the collection of the Pinacoteca Civica Vannucci and then the National Gallery of Umbria, where it remains today.

If the altarpiece was not finished until at least 1504, another aspect also comes into play, namely the relationship with his pupil Raphael: the latter in 1504 was completing the Marriage of the Virgin destined for the chapel of St. Joseph in San Francesco in Città di Castello and now housed in the Pinacoteca di Brera, exemplified by Perugino’s similar work originally destined for Perugia Cathedral and now instead preserved in Caen. In his work, Raphael arranges those present in a semicircle, and Perugino may have been inspired by this very model for the painting depicting theCoronation of the Monteripido Altarpiece.

By contrast, Raphael may have been inspired by the Crucifixion of the Monteripido Altarpiece to make the Gavari Crucifixion, the date of which also fluctuates between 1502 and 1504; the Urbino executed it in Città di Castello and it is now in the National Gallery in London. The issue is more complicated, however, because, as Paul Johannides argues in his monograph Raphael, the Monteripido Altarpiece may not have been begun by Perugino before 1504, and in this case would therefore be later than Raphael’s work. However, the uncertainties about chronology give pause for thought, because if it was Raphael who was inspired by Perugino it would mean that Vannucci, even in his mature years, was still a model to follow, a point of reference for the Urbino, because he was able to innovate, thus negating the general idea that the painter’s mature production sees only the reiteration of repetitive formulas while in reality it is still rich in experimentation; on the contrary, if it was Perugino who was inspired by Raphael it would mean that Vannucci was still an artist receptive to novelty.

The Monteripido Altarpiece is one of Perugino’s most peculiar masterpieces both because of the fact that it is painted on two sides and because of the contrast noted on the side of the Crucifixion between the dramatic wooden crucifix and the quiet figures of the saints and the contrast noted between the recto and verso, more evocative and “expressionist” the one and more usual and quiet the other, although the experimental aspect is not lacking. So, a masterpiece that holds many insights and for this reason deserves to be better known.

The article is written as part of “Pillole di Perugino,” a project that is part of the initiatives for the dissemination and diffusion of knowledge of the figure and work of Perugino selected by the Promoting Committee of the celebrations for the fifth centenary of the death of the painter Pietro Vannucci known as “il Perugino,” established in 2022 by the Ministry of Culture. The project, edited by the editorial staff of Finestre Sull’Arte, is co-financed with funds made available to the Committee by the Ministry.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.