The missing Caravaggio resurfaces in an ancient lithograph by Philippe Benoist

It is the oldest reproduction of the Oratory of San Lorenzo in Palermo. A nice rediscovery if, dating back to the mid-nineteenth century, if black lost memory. And with good reason, taking into account that it was published in a bibliographical work that is in fact untraceable today: it is the series L’Italie Monumentale & Artistique. Vues et Monuments Dessinés d’après nature par Ph. Benoist et lithographiés aux deux crayons par Bachelier, Ph. Benoist, et Jacottet. It came out in handouts between 1845 and 1852, for the Parisian publishers Bulla and Delarue, and volumes like these were sooner or later dismembered to sell the individual images imprinted on each page. Here, then, is the Church of the Company of St. Lawrence, so named in the precise bilingual caption, which has just been acquired on the Messina antiquarian market and is now happily back on display in the place where it was conceived.

Of the author Philippe Benoist, who devoted himself with brilliant results to the lithographic technique illustrating from life monuments and views in his many travels, it is significant to know that he was a pupil of the father of photography Daguerre. And meticulous do indeed appear his reproductions, as can be clearly seen from inside the Palermo Oratory. A scene, this one, that allows us to go back in time, in the environment that has remained almost unchanged since then, but enlivened by the presence in period clothing of commoners and the artists themselves intent on copying. However inconceivable today, it even makes one smile on the right side to see the little dog resting on the precious benches inlaid with ivory and mother-of-pearl. On the opposite side, leaning against the base of the triumphal arch, an old model confessional.

|

| The lithograph Eglise de la Compagnie de St. Laurent/Church of the Company of St. Lawrence, by Philippe Benoist (part.) |

|

| Loratory of St. Lawrence today |

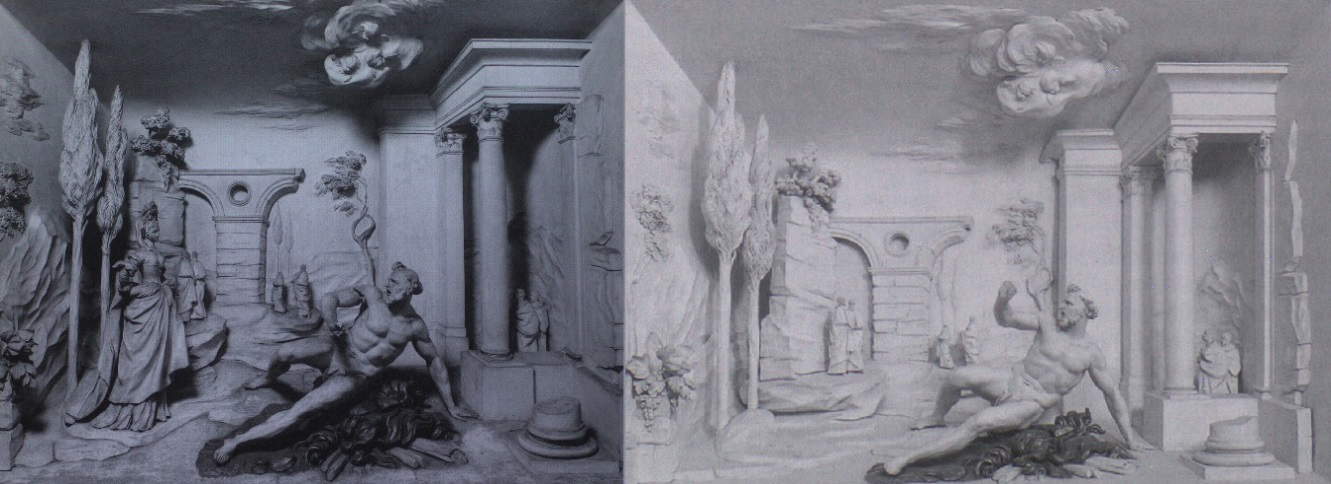

Excerpted from the Royaume de Naples section of LItalie Monumentale, the lithograph was exhibited in 1848 at the historic Salon de Paris and is recorded at the legal deposit in May 1847. Already absent, therefore, is the vault fresco by brothers Giacinto and Domenico Calandrucci (1706-1707), which collapsed in an earthquake in 1823. Instead, some of the statuettes, vandalized years ago, of Giacomo Serpotta ’s stucco theaters with stories of Saints Lawrence and Francis (1700-1705) are documented.

|

| Giacomo Serpotta’s Temptation of St. Francis, before and after the disappearance of the figure of the harlot |

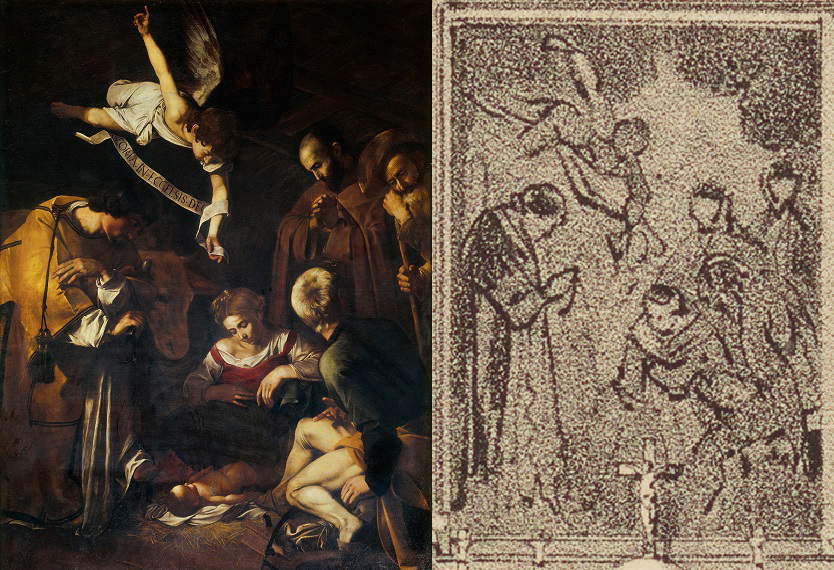

What is more, chronologically later than his two known ancient copies (one in Catania and the other formerly in the Federzoni collection), Benoist gives us back a striking reproduction of the Nativity that Caravaggio painted in the 1600s. Although, in its small size and in the half-light of the chancel, it is necessarily stylized and with some license: perhaps misinterpreting the dark background or at any rate for issues related to the legibility of the work, the ceiling of the hut becomes a sky with clouds.

On this tenuous image, everything converges perspectively and focuses the attention of the many connoisseurs of the great Lombard. With the hope that, now that the theft that occurred in 1969 is being investigated again, like this lithograph the Nativity too may one day make its way home.

|

| Caravaggio’s Nativity compared with its reproduction in Philippe Benoist’s lithograph |

Appendix

Since 1847, it would have to wait until at least 1902 for an early shot of the Nativity to be popularized through a printed work, which was also not easy to find and has remained unknown to most: this is the Kunsthistorische Gesellschaft für Photographische Publikationen, a German series with annual issues of large-format illustrations (in the specific issue, the picture is attributed to Merisi by tradition). Limmagine, sepia-toned, apparently not identical though very similar to one of unspecified source and date preserved at the Fototeca Longhi (no. 0970128), would moreover document the painting prior to an early twentieth-century conservation intervention. Liconografia caravaggesca however will become known to a wider audience through the photograph (by the Palermo studio Incorpora) published in 1922 in Matteo Marangoni’s Il Caravaggio. It appears, however, to be a pale and uncertain illustration, as described in a 1925 article by Filippo Meli, who at the same time published one of better quality (probably of Anderson/Alinari provenance).

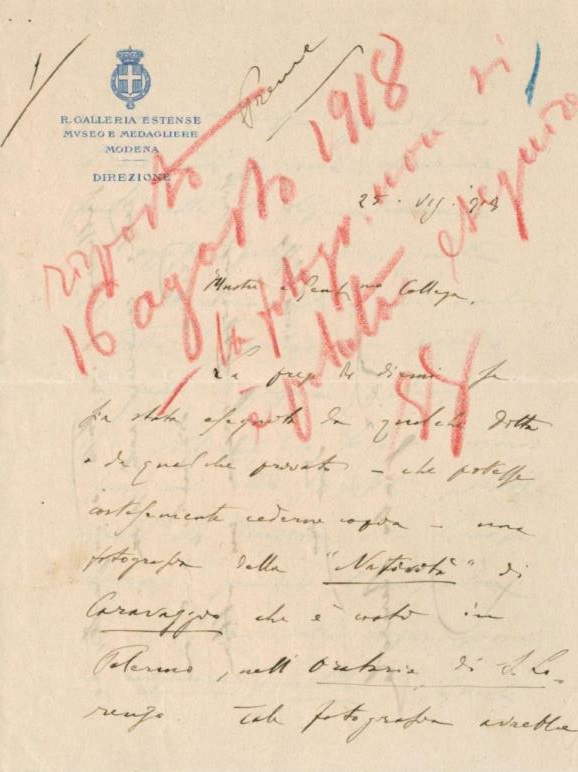

All the growing curiosity on the part of scholars, around those years, for the ’distant’ island masterpiece emerges in a letter by Giulio Bariola dated July 25, 1918, on the letterhead of the Regia Galleria Estense in Modena, preserved in the Historical Archives of the Soprintendenza BB.CC.AA. of Palermo. Bariola asks if a copy of a snapshot of the painting has been made and can receive it, which would be of such great interest to him that he proposes to contribute to the expense through the Gallery, in case a photo (specifying: the best possibleone) should be specially taken. But the outcome of the request, laconic and affixed in red pencil on the same with a date of August 16, was not what was hoped for: the photograph could not be executed. Evidently, with World War I underway and limited means available, the unfortunate Caravaggio in Palermo was not a priority.

|

| The request sent by Giulio Bariola to the Superintendency in Palermo. |

Bibliography

- Michele Cuppone,

- The

- Palermo Nativity : first altarpiece for Caravaggio? in Tactile Values, 9 (2017), pp. 61-83

- Roberta Lapucci, Caravaggio’s Palermo Nativity.

- New considerations from scientific analysis in Tactile Values, 9 (2017), pp. 84-89, in part. 86-87

- Pierfrancesco Palazzotto, Giacomo Serpotta .

- The Oratories of Palermo. A

- historical-artistic guide, Kalòs, Palermo, 2016

- Francesco Paolo Campione, Palermo .

- Memoria di una capitale, Kalòs, Palermo, 2013, pp. 177-179

- Paolo Emilio Trastulli, Rome, grandeur and splendor. Through an unforgettable visual narrative relive, in the lithographs of Filippo and Felice Benoist, the face and atmosphere of the eternal city on the eve of Porta Pia, Newton Compton, Rome, 1987, pp. 11, 245

- Jean Laran, Inventaire du fonds français aprés 1800, vol. 2, Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris, 1937, pp. 202, 211

- Filippo Meli, Lultima opera del Caravaggio in Daedalus, 6 (1925), pp.

- 229-234

- Matteo Marangoni, Il Caravaggio, Luigi Battistelli, Florence, 1922, pl. XLII

- Woldemar von Seidlitz, The Publications of the Kunsthistorische Gesellschaft für Photographische Publikationen in Leipzig, 1895 to 1901, in LArte, 5 (1902), pp. 189-190.

- Kunsthistorische Gesellschaft für Photographische Publikationen, 8 (1902), pl. XVI

- L’Italie Monumentale & Artistique. Vues et Monuments Dessinés d’après nature par Ph. Benoist et lithographiés aux deux crayons par Bachelier, Ph.

- Benoist, et Jacottet, Bulla-Delarue, Paris, 1845-1862

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.