The mild abstractionism of Gabriele Landi

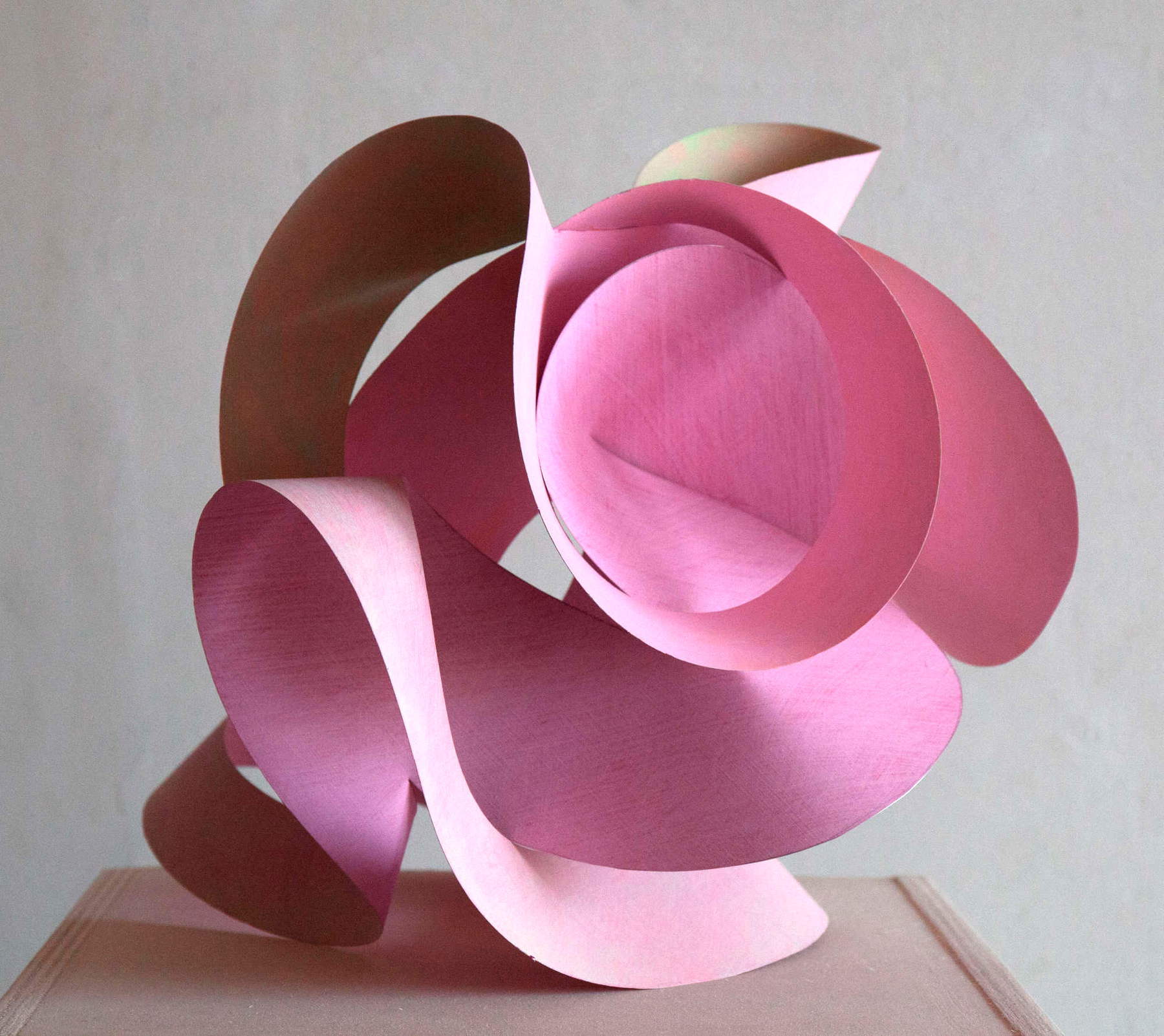

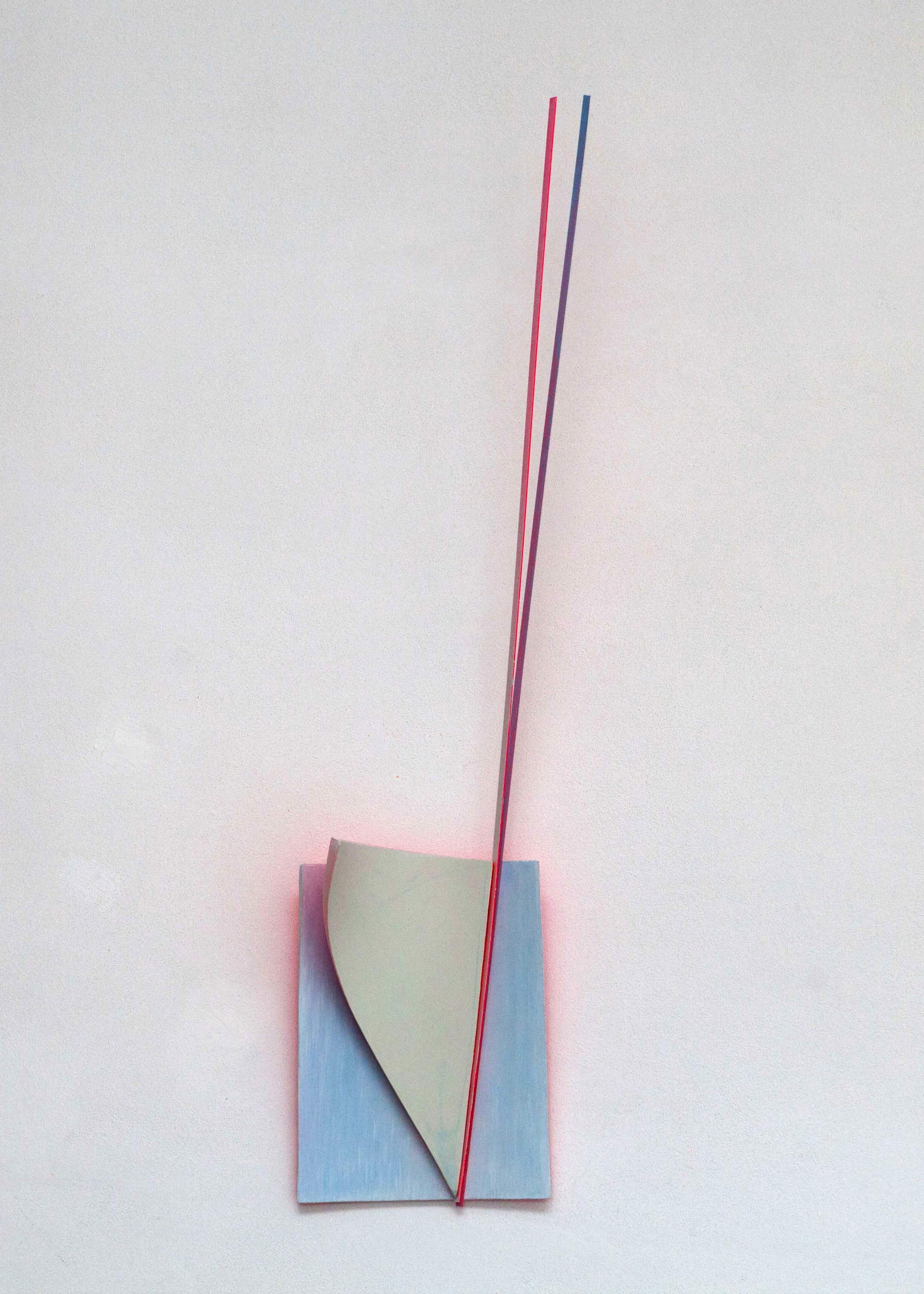

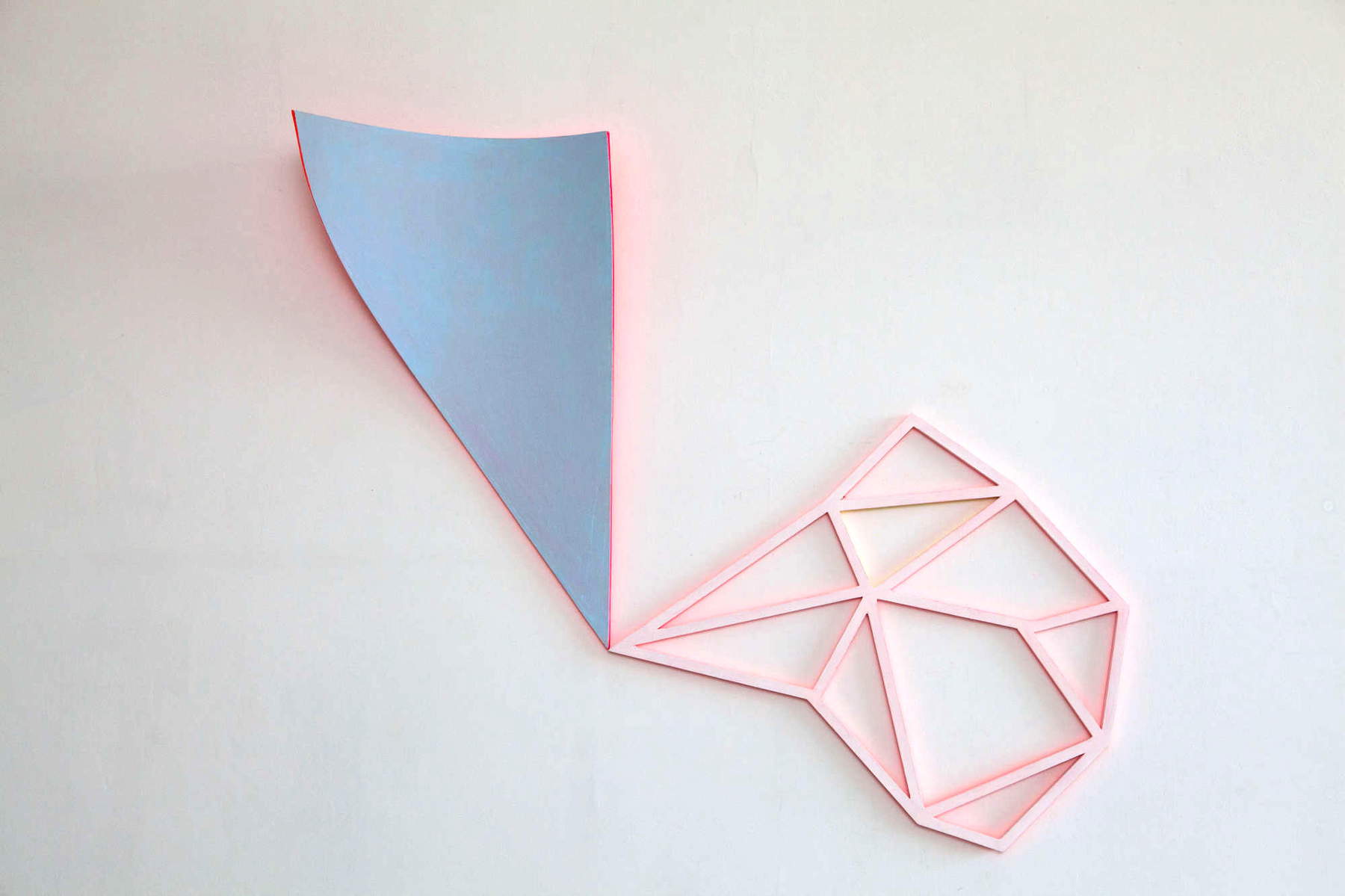

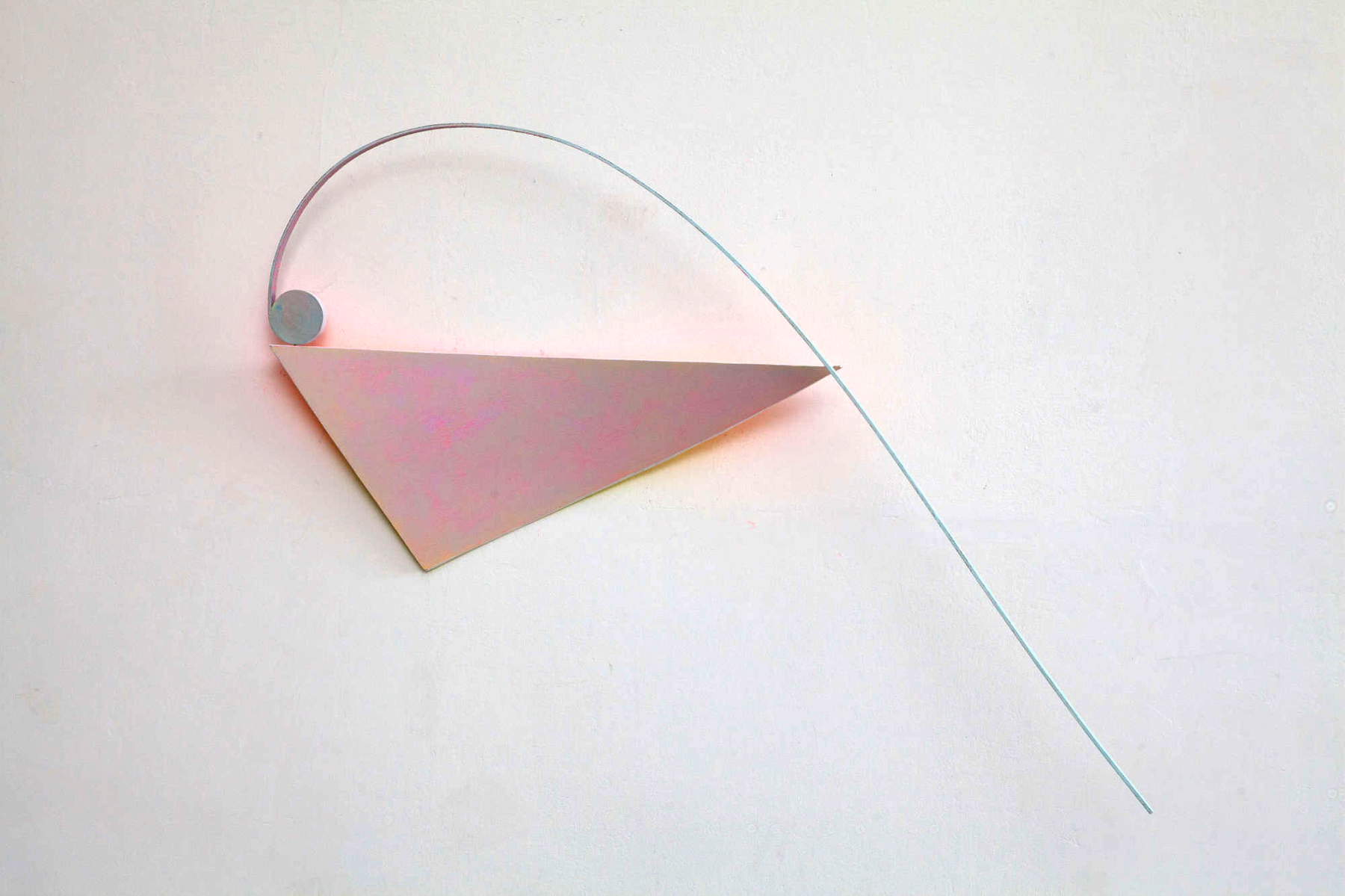

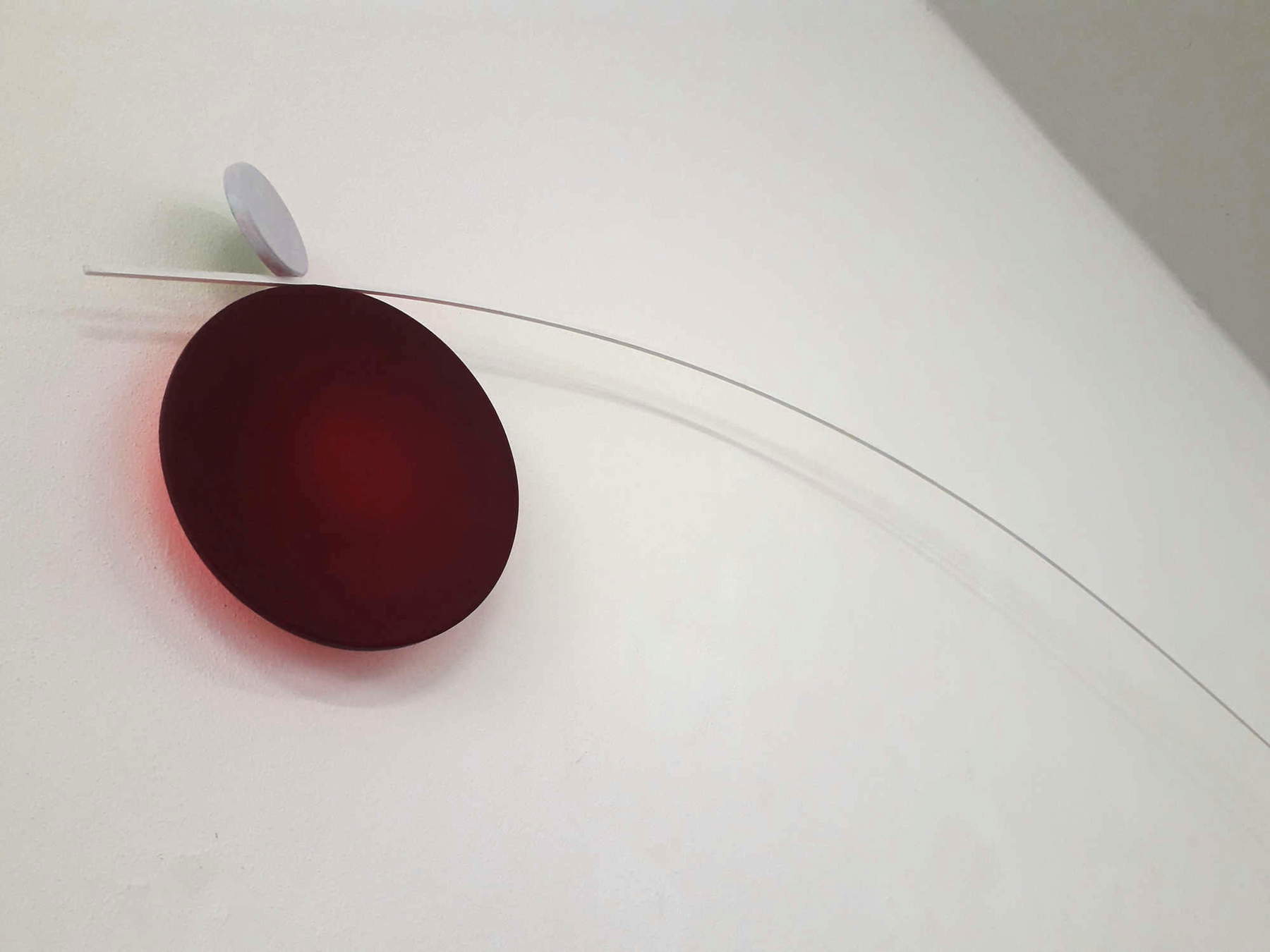

For some time now, Gabriele Landi has taken to making cardboard or aluminum sculptures that always start from thin, light, simple sheets. They have inaugurated a new strand in his research, a refined, constant quest, always striving to explore the boundaries of geometric abstraction. They do not bear a collective name, these sculptures. However, their author prefers to call them “sculptural objects,” because the process that gives life to these works is far from the traditional canons: the forms arise first from the cuts that Landi applies to the sheets, and then from the folds, the evolutions, the revolutions, the distortions that the sheets undergo under his hand. The form does not descend from the artist’s thought: it is the result of a continuous twisting, of an encounter between the artist and the material that inevitably becomes clash, contention, and then again dialogue, collaboration. At first, Gabriele Landi’s sculptural objects might call to mind Bruno Munari’s “wearable sculptures,” to which they come close above all because of external, formal affinities, but with which they also share, at least to a certain degree, their nature as objects “with an aesthetic function,” Munari would have said. “The sculpture is presented folded in an envelope. You open the envelope and take out the sculpture. Place the sculpture on a horizontal plane (on inclined planes it slips) and before you turn off the light observe how it illuminates the various protruding or recessed parts, the solid and hollow parts. Turn it the other way, it changes its appearance, your thoughts from practical will slowly become aesthetic (the speed depends on you), you will no longer wonder ’cusa l’è chel rob ki’, and you will fall asleep happily.” Up to a certain degree, it has been said, because Landi’s sculptural objects escape his intentionality, they are the response of matter deaf to the artist’s urgings (who, however, does not feel frustration at his inability to tame it, far from it: he ends up working together with the matter), but not only that: he sees his objects as a kind of metaphor for the dualism between nature and culture, for the relationship that human beings weave with everything around them, an ideal referral to the challenge that, in every age, humanity addresses to nature, and that ends up bringing out the fragile condition of human beings. The lightness of Gabriele Landi’s sculptures evokes, after all, this sense of contention and, at the same time, of fragility, of insecurity(Solide incertezze was just the title of the exhibition in which, for the first time, the Ligurian artist exhibited his “sculptural objects”).

Perhaps, however, speaking of “lightness” is hardly appropriate, since it is an irredeemably ambiguous noun. Certainly: the critics and scholars who have juxtaposed it with Munari’s work are no longer counted, to bring out the ease, delicacy, and irony of his works. Munari’s lightness is the same lightness as the flight of a butterfly, the snow that whitens the top of a mountain, the breeze that cools the shoreline at the end of a summer day. However, it is true that this noun has been abused inordinately: it had already tired Beniamino Placido in 1996. “For God’s sake, let it stop”: he began thus in one of his articles that year. “We can’t get enough of this craze for ’lightness,’ for ’lightness.’” And he placed all the blame on Italo Calvino’s American Lectures , responsible for having cleared the way for the extravagance of lightness, the overciting of lightness for any occasion. Calvino (hadn’t he ever said that!) spoke of “lightness of thoughtfulness.” And all his lightweight followers took him so literally that he established the abolition of the specification complement. Always Calvin’s fault, though: “pensiveness” refers to an etymon that is the exact opposite of “lightness.” And the oxymoron is the heaviest rhetorical figure there is. Lightness then becomes a condemnation where it masks the absence of thoughtfulness, where it intervenes to extinguish any attempt to go deep, when it dampens gravitas, when it becomes a blanket that obscures complexity. In a word: when it becomes superficiality. For Gabriele Landi’s works then one could indeed speak of “levity.” A less equivocal noun. Lightness has to do with weight, levity has to do with intensity. Levity is touch cloaked in grace: the ear of wheat that tilts in the noonday sun is “all lume and levity of grace,” wrote D’Annunzio. Levity is finesse that does not lose its consistency: the colors of Federico Barocci’s Madonna of the Clouds are both light and severe, wrote Andrea Emiliani. Levity is thought that is dressed in delicacy.

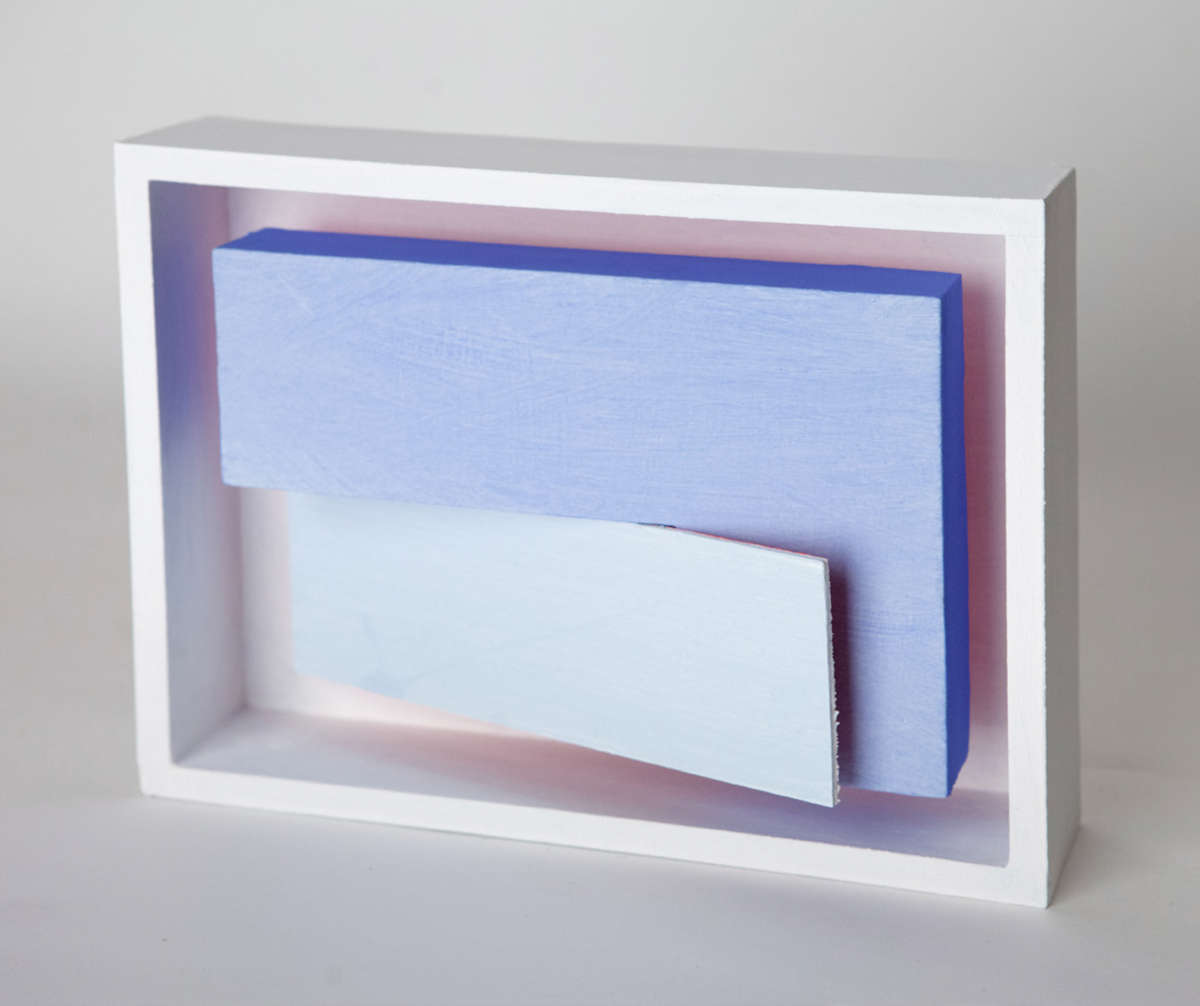

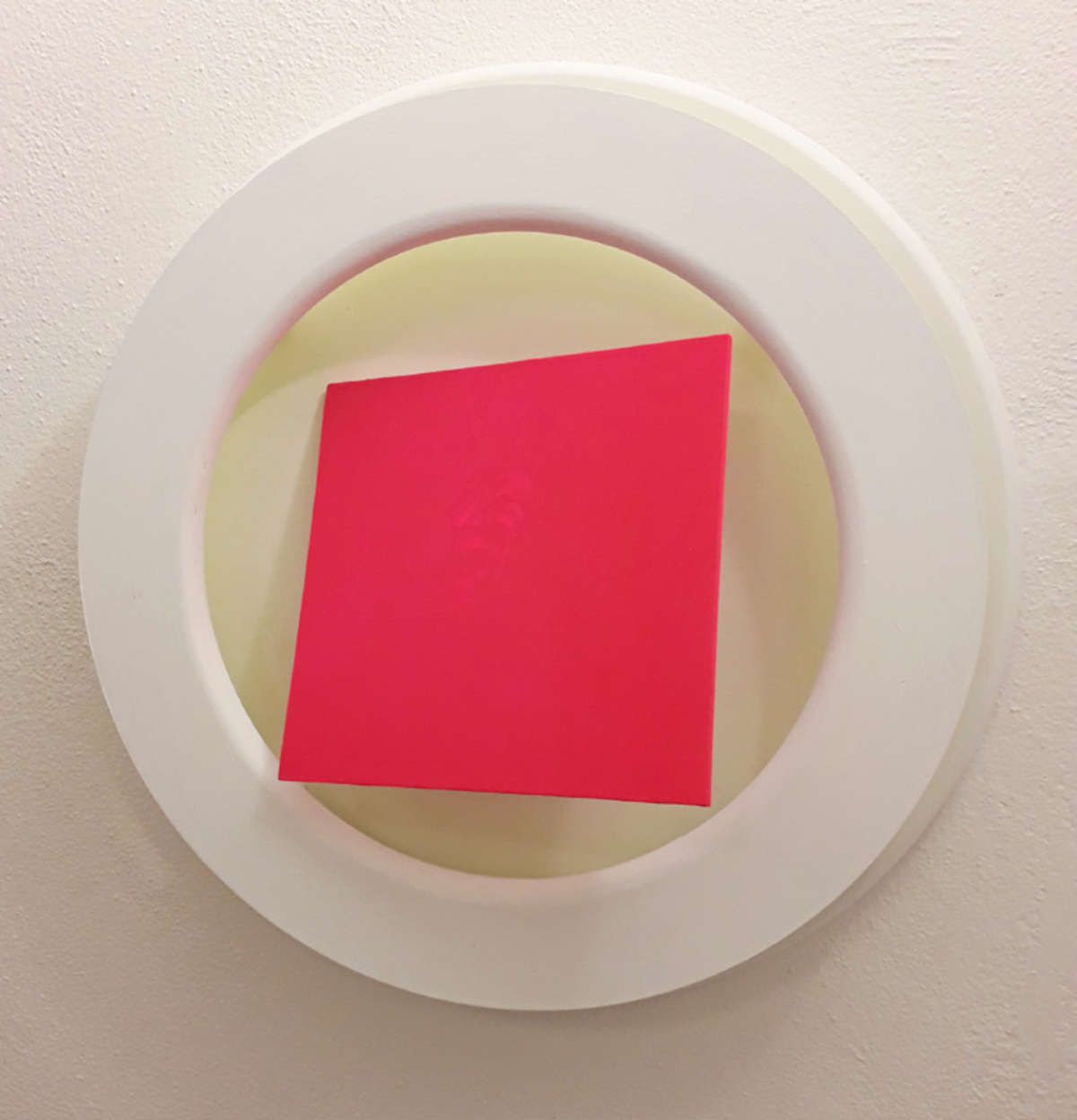

One does not struggle to find the right term to describe the poetry of Gabriele Landi’s works because he himself comes to the rescue. In 2021, in the eighteenth-century spaces of Vôtre, Carrara, he had held an anthological exhibition to which he had given the title Lieve svanire, which changed by one vowel the verse of a song by Marlene Kuntz (for them, it was “slight fainting”). In the song’s video there were ears of corn, there were clouds, there was fog, there were soap bubbles, there was Cristiano Godano scattering feathers in the air. In the eighteenth-century rooms of Vôtre were the fruits of Gabriele Landi’s research that continued the tradition of Italian geometric abstractionism of the second half of the twentieth century, that, for example, of a Dadamaino (think, in this case, of the works without optical or kinetic implications: he is an artist whom Landi himself, moreover, indicates among his references), of a Nangeroni, of a Mario Nigro, of a Pino Pinelli, continued then with the works of the artists of the following generations who opened those experiences to welcome suggestions that crossed national borders from outside (Giuliano Dal Molin and certain things by Alfredo Pirri come to mind, above all). Painted wooden sculptures, those of Landi, pure geometric forms that put Italian geometric abstractionism in dialogue with the Russian avant-garde of the early twentieth century (the work To Russia with love makes its Suprematist and Constructivist sources clear from the title), or new forms born from the encounter of pure forms, circles and triangles on which are’wires and stripes that increase the sculptural dimension of the polygons in two dimensions, always with pure colors, and painted on the back with intense tones to make the works shine, to illuminate them with a light that is lit only with the medium of color, to make the forms float above haloes of pink and orange, so strong as to generate in some visitors to the exhibition the doubt that the works were backlit. No artificial light, really: it is the power of color, it is the “reverberation of painting,” it has been written for Alfredo Pirri who has experimented with similar modalities, the desire of painting to leave the boundaries of the work and expand even beyond the material. The titles of Gabriele Landi’s works are evocative, echoing situations and dimensions to be grasped beyond the appearance of forms, but starting from the forms: In bilico, Pittura non eloquente, Un giorno greve, Trappola, Colpevole, Dove sei?, Soliloquio, Sintomo scialbo, Stratagem della rottura. Suggestions for reading: the burden of deciphering them, of going beyond the surface, falls, however, as is obvious, on the relative. However, it will be convenient to return to this point later.

That “slight fading” of the title was intended to gather under one whole everything that united Gabriele Landi’s more ’pure’, we might say, research: “the levity of certain situations,” he said on the occasion of that exhibition, “determined mainly by the chromatic tones, in close agreement with the forms that welcome them; on the other hand, the progressive vanishing, again by means of color but not by the work of its chromatics this time: by means of its consistency, of a series of mysterious presences that persist in my paintings.” A color, inspired as always by the colors of the sky (blues and pinks prevail then), so slight as to become almost evanescent. What then is this levity that permeates all Gabriele Landi’s works, including the most recent ones? It is, meanwhile, characteristic of the object that never fully reveals itself, never shows itself all at once, never swaggeringly imposes itself on the viewer. It is, rather, an elegant, discreet, delicate, airy, subtle presence. It is a condition of the work that eschews intrusiveness, shuns overbearingness, and avoids the cage of meaning, at least in the sense that is proper to a large part of the public, which is often inclined to equivocate meaning for narrative (today many, too many believe they are in search of meaning, when they are simply trying to be told a story). Gabriele Landi’s levity, on the contrary, is the work’s ability to envelop meaning, a meaning moreover never unambiguous, with its delicacy, its purity and its mystery. It is then a game, a fine provocation, the charm of a work that does not want to strike the observer directly, but rather tries to be, in the meantime, an aesthetic object à la Munari, an object whose meaning resides in its form, in its appearance and in the substance that appearance suggests, and secondly an object that opens up openings to completely unexpected meanings. It is the graceful face of a solid thought, of an art that renews a tradition. It is also, one might think, an absence of methodicality, despite the rigor of the forms might suggest otherwise.

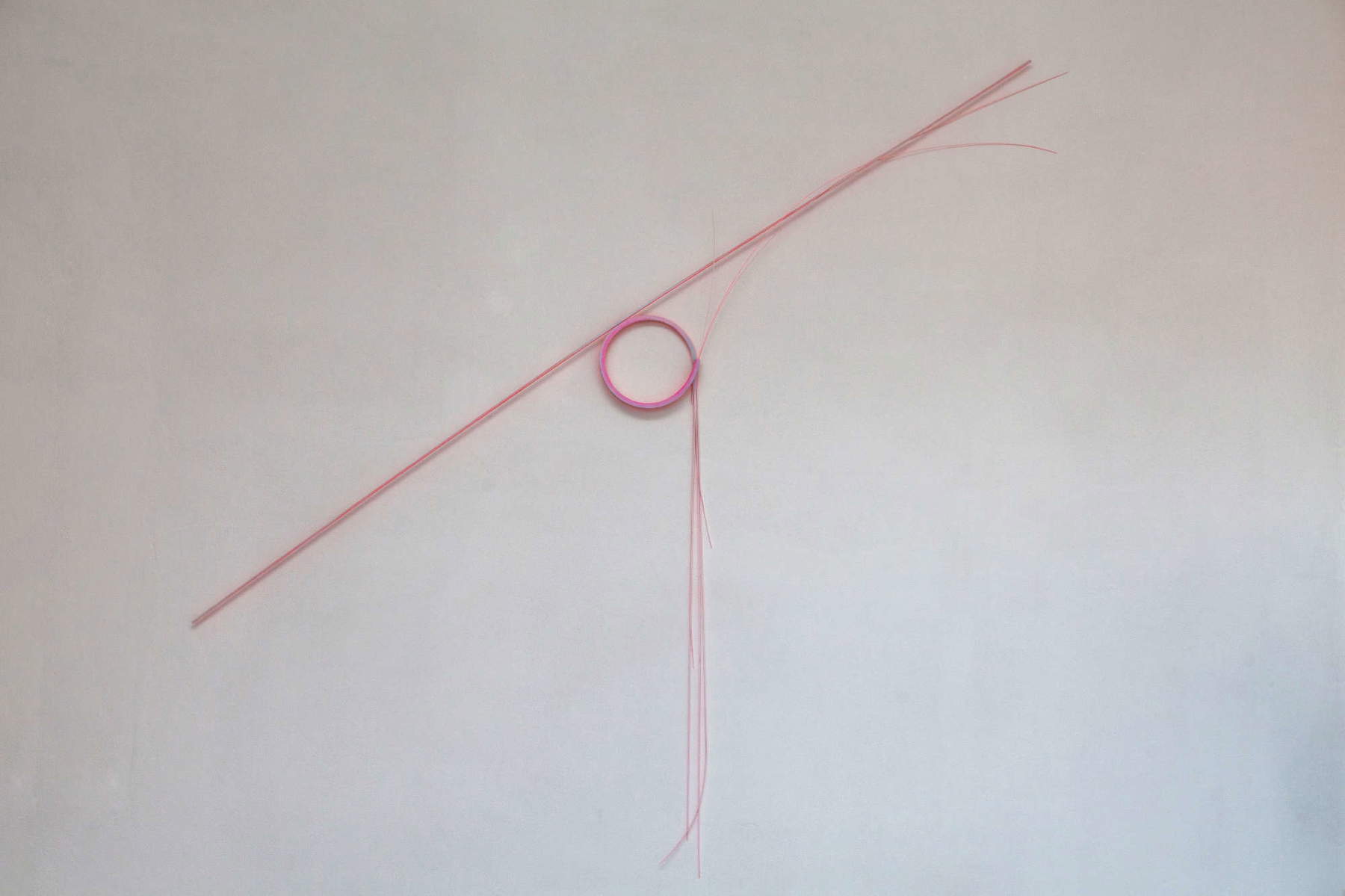

Visiting Gabriele Landi’s studio, a large room in Ressora, a busy commercial township between Sarzana and La Spezia, is useful to realize how his works come into being: Landi hardly waits for one project at a time, many of his works are born and grow simultaneously, are suspended and then resumed, strands that seemed dormant suddenly reawaken and return with some constancy. Fruit of the curiosity of an artist devoted to continuous investigation, and the space where the works are born is the most concrete image of this incessant eagerness to experiment. It is theatelier of a true artist who lives in the midst of the rigorous disorder of his ideas. It is the forge where Landi piles up his aluminum sheets, his rolls of paper, where he stacks the boards from which his sculptures will be born, where one also comes across curious tools that Landi makes himself to facilitate his work: there are for example some rulers (two meters or so high) with various proportions that he uses for his carved papers. It is workshop in a broad sense, since for a few years it was home to the Aurelia Sud project, with which Landi invited several colleagues to confront the bottom sign (at one time, what is now his studio was a business): those invited to participate created a work of art that occupied the sign’s place for a few months, offering the Aurelia traffic flowing alongside the studio the sight of an ever-changing work. A project that can be considered, in some ways, a product of the critical activity that Landi has been conducting for some time with his Parola d’artista project with which he continues to do a very valuable, original, constant work of popularization, of bringing the public closer to the artists Landi has been interviewing for years for his pages. And then the studio is also a testing ground for exhibitions, since the size of the walls allows Gabriele Landi to imagine how his works might succeed hanging inside a gallery or inside a museum. It happens then, when he is working towards an exhibition, to visit him and already see a sort of preview of what the public will see during the official occasion. In recent months, for example, the studio walls were overflowing with carved papers.

It is these papers that give substance to the most recent vein of his production. Three large papers, each more than five meters high, were the centerpiece of the exhibition Alle montagne (To the Mountains), Gabriele Landi’s solo show at MudaC in Carrara in the summer of 2024, with a title that evoked Il testamento del capitano(The Captain’s Testament), the famous song of the Alpini, to sing a tribute to the mountains of Carrara. Three monumental papers, the three largest works he has ever done, which occupied a large wall at the Apuan museum, executed with patient carvings that Landi worked on the surface of the paper for seven months, unprecedented expressions of a research that, with this challenging work, explored new areas of that borderland between painting and sculpture in which Gabriele Landi’s art has continued to move since the first moments of his career. The process is apparently simple, regular: the carvings are all square (in that case of one centimeter by one, but the size of the cut varies according to the size of the sheets), and they follow a pattern that is not, however, pre-established. It is a continuous flow, it is a writing, a slow, patient, meticulous weave of signs, indebted to Dadamaino’s research (this time, yes, the ones close to kinetic art), to Enrico Castellani’s pieces of infinity, to Irma Blank’s nonverbal graphics. A fabric of openings and closures capable of evoking the orography of the Apuan Alps with a pattern made of proliferations, accumulations, thinnings, progressions, voids and fullnesses, steep ascents and impetuous descents, regular stretches and disordered masses, rarefied presences and masses with a strong, vigorous, volumetric consistency. The result is a fascinating landscape, articulated, three-dimensional though firmly anchored in the second dimension, an imaginative cartography with signs and openings capable of becoming valleys, peaks, quarries, ravines, the potential of the map pushed to the point of making it take on the consistency of the mountain though without evoking its physical concreteness. It happens when Landi has in mind a landscape he knows, but it also happens if the paper has to reconstruct the map of a place where the artist has never been: Antarctica, for example, at the center of a large sheet intended to reproduce a kind of imaginary landscape, an interior mapping of the frozen continent that the artist can traverse only with his imagination, that is, with that extraordinary medium that, to recall Munari again, allows us to imagine something that already exists but is not currently within reach. This, too, is levity: not so much to reproduce the landscape, be it the landscape of the Apuan Alps or that of Antarctica, and perhaps not even to grasp its essence, as, if anything, to touch what that landscape is capable of arousing, echoing Georg Simmel’s Essays on Landscape (“the landscape contains [...], already in its immediate reality, an element akin to art, a trait of self-sufficiency and intangibility, by which it frees us inwardly, dissolves our tensions, transports us beyond the limits of a momentary destiny”). That’s it: the art of Gabriele Landi, when he intends to evoke a landscape with a carved paper (but also a sky, a constellation, even the sheet of a notebook), succeeds in capturing the ineffable, in capturing the intangibility of the landscape by means of abstraction alone.

Color, in all this, takes on the contours of a force that holds everything together and leads every gasp, every emotion, every feeling back to the purity of abstraction. Blue and pink, it has been said, are the predominant hues: the choice stems from a fascination with Giambattista Tiepolo’s skies. A sweet obsession that expresses itself in an attempt to capture its nuances, evoke its vertigo, recall a cloud, a flash of serenity, the flight of an angel. In front of his eyes a paper to be painted, in his mind the image of the ceilings of Ca’ Rezzonico in Venice: “Right away I was won over by wonder,” Landi says, recalling Tiepolo’s skies. “To see a few meters above my head a quadriga of horses, rampant, pulling a chariot governed by Apollo is a real spectacle. On the chariot of the sun god sits a maiden of noble birth, and all around are winged cherubs and a host of other figures, propelled upward by vaporous clouds: the whole is silhouetted against a sky streaked with pink, blue and yellow. The characters’ bodies are wrapped in iridescent cloths, and some of them brandish flags and insignia waving them in the air. Following the zig zag of the broken lines, which build the skeleton of this wondrous stage machine, I also climb upward. I almost feel as if I can touch the clouds, the textiles: I go up again and there is the chariot, the putti, in an exhilarating crescendo and then higher still, enraptured by the compulsive and fast rhythm of the brushstrokes, bouncing among the flickers of light.”

Color, in Gabriele Landi’s work, is the medium through which the work dialogues with space. Wolfram Ullrich, who is among the pioneers of German geometric abstractionism, would say that color, however free it may be, still needs a material support to contain it: from this observation his search for a pure color that is, however, enhanced by the steel borders of his works to allow its expansion beyond the limits imposed by the support, because a contrasting border allows the color to move according to the point of view assumed by the viewer of the work. Landi, on the other hand, employs other means to achieve this dialogue between painting and space by means of color: refractions in sculptures on wood, the play of light and shadow in sculptural objects, the very openings in carved papers. Color is then a means that serves to protect the work, in some way, although it is not the only tool Landi adopts for this ’conservative’ end, let us call it.

His idea is that the audience should not only be involved from a visual point of view: the invitation, he explains, is “to look well at what is in front of you, and maybe even discover something that at first glance, and maybe even at second glance, and for those who are more distracted at third, sometimes escapes. There is always something that one does not notice at first glance: sometimes these are deviant situations, that is, capable of highlighting something different from the type of language used to do that precise work.” Concealing, for Gabriele Landi, is not only an aesthetic expedient: it is a way to preserve images from contemporary visual excesses through a process of subtraction and concealment. It is in this way that the image can regain value: through the effect of estrangement it causes on the observer. Always with a light touch.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.