On May 22, 1873, Alessandro Manzoni passed away in Milan: the great man of letters, in his 1867 will, had bequeathed his autographs to his son Pietro Luigi Manzoni, who, however, passed away a little less than a month before his father (on April 28), and consequently the autographs were divided among his grandchildren Vittoria, Giulia, Lorenzo and Alessandra. The manuscripts that ended up in the possession of Alessandra, Giulia and Lorenzo were given to Pietro Brambilla, Vittoria’s husband, who decided to leave the works to the Braidense National Library in Milan, where they are still located today (moreover, only five years earlier, in 1880, the library had been given the status of “National”). Thus, in July 1885, Brambilla sent a letter to Isaia Ghiron, prefect of the Braidense, communicating the family’s intentions, on the condition, however, that the library dedicate “a special room” to Manzoni’s works, that “mention of the donation made” be explicitly affixed, and that all the material be made available to the public and scholars.

Ghiron had the intuition to expand the collection right away, and therefore appealed to anyone in possession of Manzonian autographs (perhaps because he had met the great writer in person) to send additional works to the Braidense: the idea was successful since more donations arrived at the library, and finally, on November 5, 1886, in the presence of the kings of Italy, the Sala Manzoniana was finally inaugurated. The collection was then further increased through other arrivals, including the Ercole Gnecchi donation, which included autographs, letters and the five volumes of the printing draft of the Quarantana (the definitive edition of I Promessi Sposi, so called because it dates back to 1840), and then again the Giulia Costantini Manzoni bequest that included pieces of Manzonian iconography and the Vismara collection, which counted on rare editions of I Promessi Sposi.

Later, in 1924, came to the Braidense the memorabilia, autographs and pieces of iconography that belonged to Stefano Stampa, Manzoni’s stepson (they arrived thanks to a donation from theAssociazione Nazionale per gli Interessi del Mezzogiorno, which was in possession of them), while in 1925 the Manzonian collection was enriched by the Federico Gentili donation, which replenished the collection with 247 letters, 600 books, portraits and memorabilia that were part of the Necchi family’s collection, which came to Gentili thanks to the purchase at auction of the items put up for sale by the heirs of Isabella Gnecchi Bozzotti. The collection had become so large that, shortly before World War II, the material was transferred to the Braidense to the new National Center for Manzonian Studies. During the conflict, in order to preserve it, it was decided to transfer it to the Benedictine Abbey of Pontida, and when the war was over, the Manzonian collection returned to the Braidense to comply with Pietro Brambilla’s wishes (only the memorabilia and part of the iconography remained at the Study Center), but a new Sala Manzoniana, designed by architect Tommaso Buzzi and inaugurated on November 5, 1951, in the presence of President of the Republic Luigi Einaudi, became necessary. Currently, the Sala Manzoniana is open for consultation of the Braidense’s manuscripts and rare books, as well as the Manzonian Fund and the fund of the Archivio Storico Ricordi, and the books of the Umberto Eco Fund will soon be available for consultation.

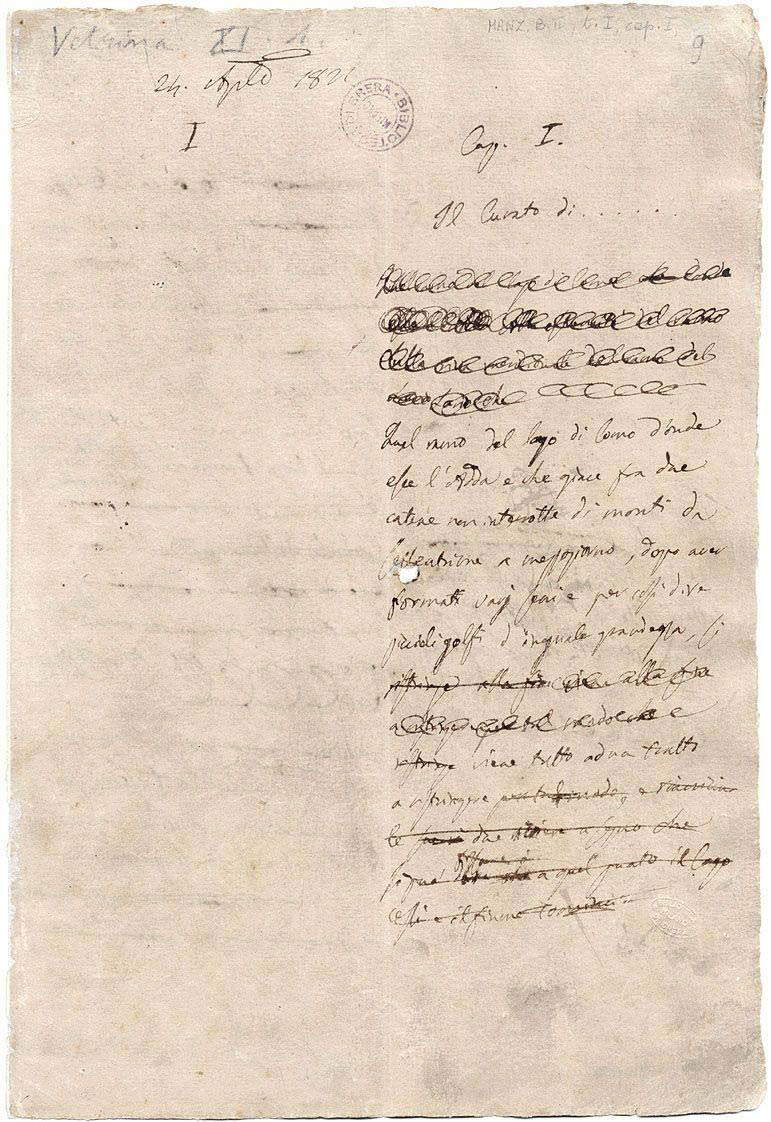

Today, the Manzonian Fund consists of 250 manuscripts (a total of about 9,000 papers), 550 volumes from Manzoni’s library of which 200 have postilles, about 5,000 pieces of correspondence, 1,000 volumes of Manzoni’s works, 1,000 volumes of criticism and 1,800 pieces placed in miscellany. Among the most important pieces is the manuscript catalogued as Manz.B.II, which contains the first draft of I Promessi Sposi(The Betrothed): the volume consists of 776 papers and documents, in the first sheet, the date when the composition of the novel began (on April 24, 1821), while the end of the four tomes of which the novel’s draft is composed bears the date September 17, 1823. “Two years of work or a little less,” explained literary critic Dante Isella, "having to take out of the account the months, from May to November 1821, in which, having suspended the narrative just begun, Manzoni occupied himself with completingAdelchi and the connected Discorso sopra alcuni punti della storia longobardica in Italia: still uncertain whether to put his hand, immediately afterwards, to the story of the two promised spouses or to a planned third tragedy, Spartacus. From notes sent to his friend Gaetano Cattaneo, datable to early 1821, we know of requests for books in the service of historical narrative: ’some book of the first half of the decimosettimo century printed in Milan, and which may give news of the facts, customs etc. of that epoch,’ while others are returned, on the gride and the subject of the plague."

Manz.

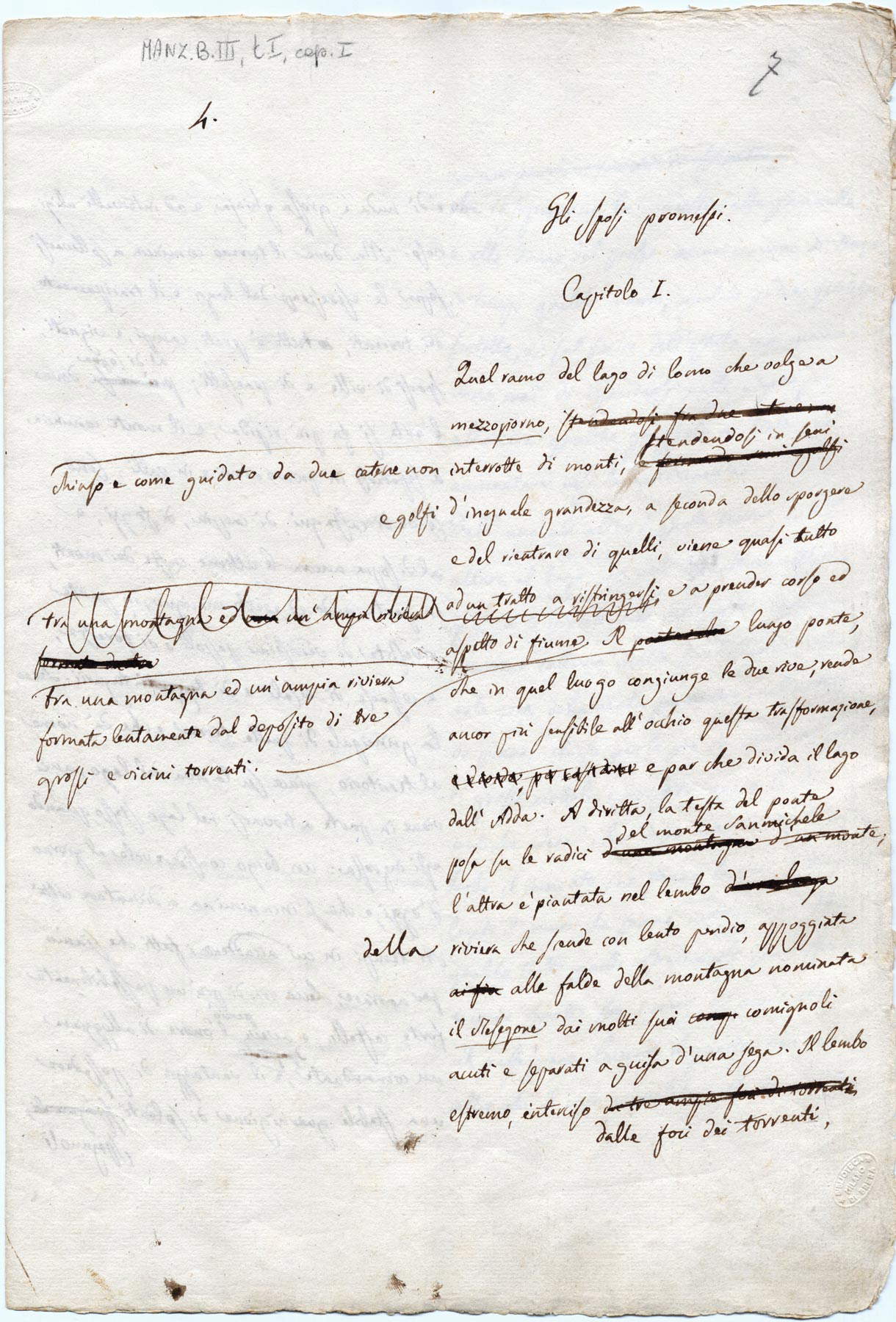

Manz.For the drafting of the novel, consultation of seventeenth-century material was of great importance, so much so that there are several requests to the director of the Numismatic Cabinet and the director of the “Great Library” of Milan (i.e., the Braidense) for loans: to give an idea of the study carried out by Manzoni, it is interesting to report that, on May 21, 1823, the writer sent a letter to his friend Claude Fauriel, a French historian and linguist, to inform him of the need to postpone a trip to Tuscany as he was too busy “consulter à tout moment quantité de livres, de bouquins, de paperasses même, dont plusieurs rares, et même uniques, et que je n’ai qu’en prêt” (“to consult at any time a quantity of books, libercoli, even paperasses, among which several rare, and even unique, and which I have only on loan”). Four months later, Manzoni informed Fauriel that he had reached the halfway point of the second tome, while he began the third on November 28, 1822 to finish it on March 11, 1823, and finally, by September of that year, the draft could be said to be complete. The Manzonian manuscript is anepigraphic, i.e. without a title: the conventional title of the first draft, Fermo e Lucia, is taken from a note written by the man of letters Ermes Visconti to the poet Gaetano Cattaneo, dated April 3, 1822, in which we read that "Manzoni has already finished Adelchi for a while [...] We will be waiting to hear what judgment the great translator will bring of it. We lack nothing else but for Walter Scott to translate him the novel Fermo e Lucia when he has done so.“ However, already in the first draft we read three times the expression ”gli sposi promessi," which was probably the title Manzoni had thought of from the beginning: this was in any case the title of the “second minute” (i.e., the second draft), which remained valid until the 1825 printing of the first tome of the Ferrario edition, and then later became I Promessi Sposi.

The text of the manuscript, composed of sheets numbered progressively by Manzoni himself, is divided into two columns: the right column contains Alessandro Manzoni’s text, while the left column had been purposely left blank by the author himself so as to have room to make any additions and changes (many, in fact, are the corrections the writer made to his novel). The mode of writing would change, however, in the second minute, when, while continuing to use the expedient of the blank column, Manzoni would also reuse sheets from the first draft by transferring them to the second and elaborating them directly in the second draft.

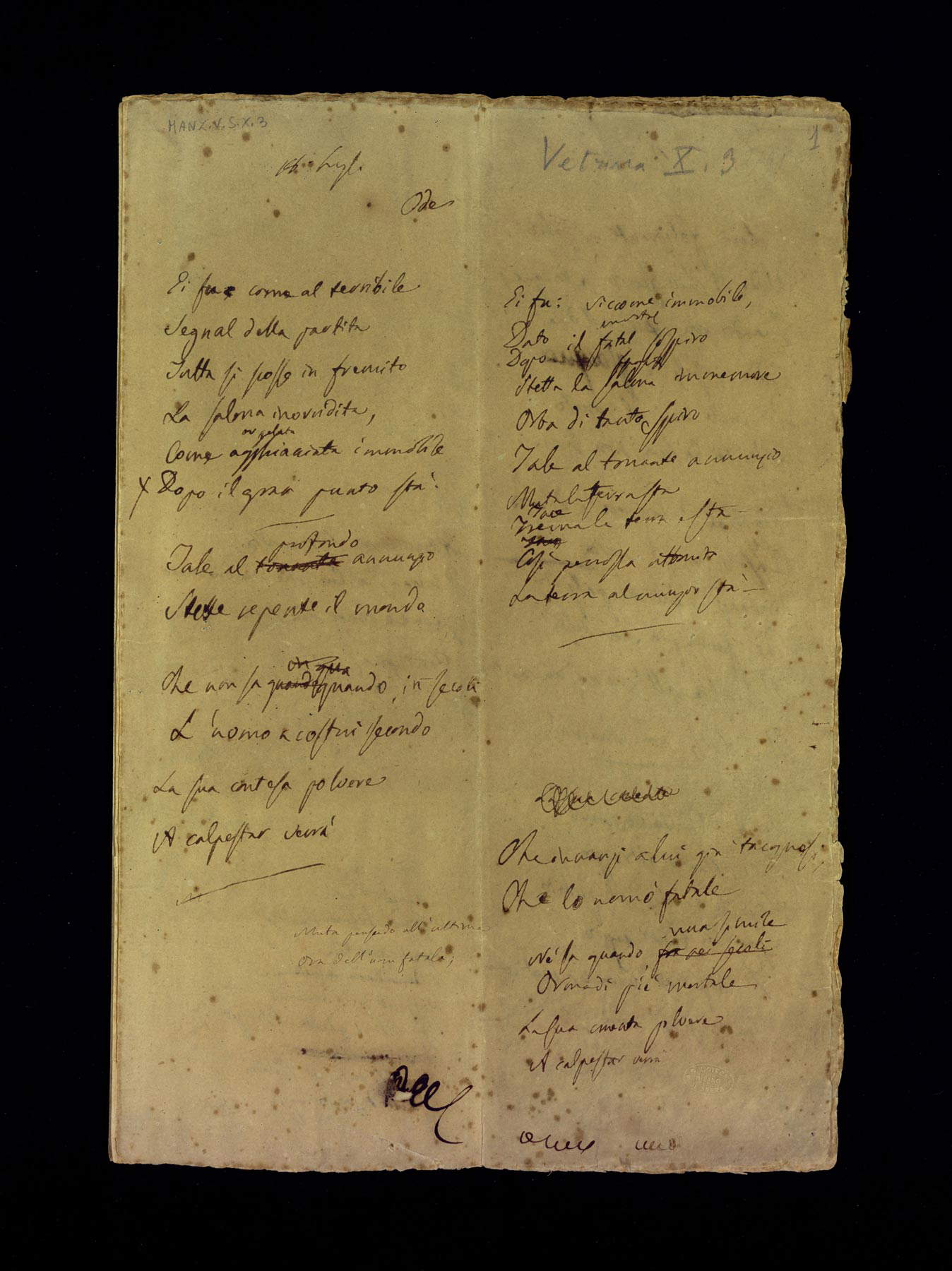

Among the most valuable items in Manzoni’s collection is the autograph draft of Cinque maggio, the ode composed in Brusuglio after Napoleon’s disappearance and finished in just three days. The poem is written on a 6-page binder and was immediately written by Manzoni after learning of Napoleon’s death, which occurred on May 5 but was not published until July 16, 1821, in issue 197 of the Gazzetta di Milano. Manzoni began the drafting on July 18 (we know this because the first sheet of the autograph is dated), completed it on the 20th, and submitted his composition to the Milan Censorship Office on July 26, in two copies as required, in order to obtain permission to publish it. One of the two copies was personally returned to him by the censor, Abbot Ferdinando Bellisomi, who went in person to Brusuglio to explain to Manzoni why the text had failed to pass the Austrian censor’s scrutiny, but the other, which remained in the Milan office, soon came out and began circulating around the city and even outside, generating numerous copies that crossed even national borders if already in 1822 Goethe published the German translation of Manzoni’s ode in his journal Ueber Kunst und Alterthum, and in 1823 the publisher Marietti published it in Turin, in a collection of Manzoni’s lyric poems. However, the first official printing would be in 1854-1855, in the first edition of the Opere varie.

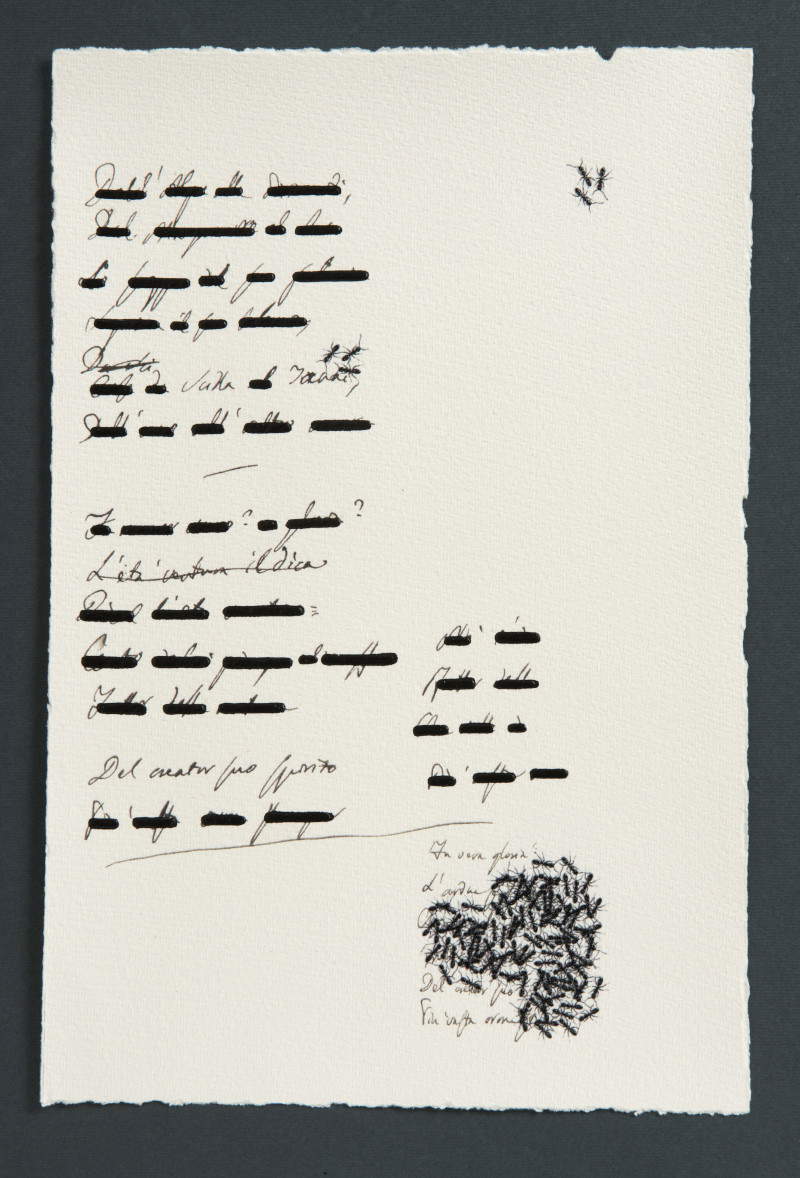

The autograph of Five May has recently been the subject of an artistic intervention by Emilio Isgrò (Barcellona Pozzo di Gotto, 1937), who has made his characteristic erasures on the manuscript of the Manzonian poem dedicated to Napoleon, in a work that was exhibited at the Braidense from May 20 to July 3, 2022, and that Isgrò donated to the institute. The work Five May. Minuta cancellata is meant to be a tribute to Manzoni: “This is the second time I have tackled the Manzonian work, and I must admit that undermining Manzoni from the throne of doubt is more difficult than emptying Napoleon of his charisma,” said the artist. “Even for Il Cinque Maggio it could only be so. I leaned on the text just as the composer leans on the libretto, letting the words speak for themselves, which the music risks erasing. It is clear that the incipit ’Ei fu’ I had to leave in its entirety, to ignite the audience’s imagination and memory.”

The Braidense National Library came into being at the end of the eighteenth century, when the Congregation of the State, a body that since the mid-sixteenth century had represented the interests of local communities in the Milan subjected to the domination of first the Spanish crown and then the Austrian crown, purchased the library of Count Carlo Pertusati, and then donated it to Archduke Ferdinand, son of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, and destined to become governor of Milan starting in 1771. The year before, Maria Theresa decided to allocate the Pertusati library to the public: the Palace of the Jesuit College of Brera was subsequently chosen as the site, which would become part of the state patrimony in 1773, following the dissolution of the Society of Jesus decreed that year by Pope Clement XIV.

Work on arranging the library (which in the meantime had been enriched by further acquisitions) in the palace began at a close pace, and in 1786 the Braidense could finally open to the public. In 1880 the Braidense became a national library, and in the meantime it had continued to see its collections grow with holdings of different kinds: ancient manuscripts (such as the illuminated choir books from the Certosa di Pavia), works on history, science, literature, law, prints, and incunabula. The Braidense thus became a large general library. Today, the Braidense is both a conservation library, bearing witness to centuries of history of Milan and beyond, and a reference library intended not only for scholars and insiders, but in general for the entire public. Finally, in 2015, the Braidense became part of the Pinacoteca di Brera museum system.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.