After a full fourteen years of closure , the Mausoleum of Augustus in Rome will reopen to the public in March 2021. The famous structure dates back to the first century BC, and was erected at the behest of the founder of the principality, Octavian Augustus, who wanted it as his own monumental burial place. Octavian initiated the work in the aftermath of his victory over Mark Antony and Cleopatra, which ended the long period of civil wars. Having eliminated his rival, Caesar’s adopted son no longer encountered any significant obstacles in his path to dominance over the Roman republic, made possible in the first place by the broad base of support he enjoyed and derived primarily from having in fact ruled in Italy and the West for a decade while Mark Antony was in the East.

Uninterruptedly from 31 to 23 BCE. Octavian secured the consulship, leaving then for a few years this office to be taken over by the other senators, who, however, now had less and less room to maneuver in the face of his growing political clout. In 28 B.C.E., the senators themselves acclaimed him Princeps senatus, while the following year, although he formally returned his exceptional powers to the senate and the people, he was given the traditionally religious title of Augustus, a customary attribute of Jupiter.

A well-known passage from the Res Gestae, the account of his own works and deeds compiled by Octavian himself (still readable right by the Mausoleum, in a modern ’bronze inscription on the retaining wall of theAra Pacis Museum) reads, “After that time I was superior to all in authority, but I had no more power than those who were my colleagues in the magistracies.” And many more were the honorary titles and offices that Octavian Augustus won or retained for life, increasingly guaranteeing himself an iron grip on the Res Publica.

|

| The Mausoleum of Augustus from above. Ph. Credit Sovrintendenza Capitolina |

|

| The Mausoleum of Augustus in 2019. Ph. Credit Jamie Heath |

|

| The Mausoleum during restoration. Ph. Credit TIM Foundation |

|

| Francesco Cellini’s redevelopment project |

|

| Francesco Cellini’s redevelopment project. |

In short, summing up this complex political framework in the words of Guido Clemente from his text Guide to Roman History, “At the summit of a formally restored republic was thus installed a single man, in fact a monarch, with powers nevertheless indefinite enough (and recallable all to the republican tradition) to allow him to be defined, formally, only as the best among his peers, the senators who had always governed the state.” It was, then, the prudent but inexorable beginning of the imperial age. And it is to the fundamental historical figure who was its promoter that we owe the construction, beginning in 28 B.C., of the first and most imposing dynastic mausoleum of Roman antiquity, likely inspired by the Royal Mausoleum of Alexandria. Nearly two centuries elapsed before another prince, Hadrian, erected a new monumental tomb looking to the illustrious Augustan precedent, on the opposite bank of the Tiber (Hadrian’s Mausoleum later became Castel Sant’Angelo).

The building commissioned by Augustus arose in the northern Campus Martius, between the river and the Via Flaminia (today’s Via del Corso), in an area at the time not yet built, already used for the burial of public figures, but also a place where military exercises were held. Not far from the gigantic tomb, years later, theAra Pacis, the altar dedicated by the Senate to the Peace restored by Augustus to Rome, and theHorologium Solarium wanted by the latter, which had for its gnomon the obelisk of Psammeticus II, brought to the city in 10 B.C., and raised after centuries of ruin by Pius IV, in 1792, in the present-day Piazza di Montecitorio, also found a place.

The Mausoleum, as much as 87 meters in diameter, was composed of five concentric annular walls between which were inserted corridors and spaces articulated in concameras that were not usable with a static function. According to recent findings and Strabo ’s description of it in his Geography, on the outside the building must have appeared as a mound covered with evergreen trees, resting on a base lined with travertine slabs and surmounted by a cylindrical marble body with a bronze statue of the prince as a solemn crowning glory.

The entrance was on the southern side and was preceded by two granite obelisks from Egypt, recovered at different times and now placed one in front of the apse of Santa Maria Maggiore, the other on the Quirinal. Next to the entrance were bronze tablets bearing the text of the Res Gestae.

Inside the structure was the actual burial cell, surrounded by an annular corridor and equipped with three rectangular niches in which the urns with the ashes of the dynasty’s most illustrious dead were kept; in the center a pillar contained a small square-shaped room that constituted the tomb of Augustus, corresponding with the bronze statue that towered outside, on top of the pillar itself, at a height of more than 30 meters. Among the emperors found burial in the mausoleum were Augustus, Tiberius, Claudius, Vespasian and Nerva, while Caligula and Nero were excluded for unworthiness. But the building also housed the remains of Livia, Marcellus (grandson of Augustus and dedicatee of Rome’s famous theater), his mother Octavia, Agrippa and his sons Lucius and Gaius Caesar, Agrippina Major and Poppea (Caligula’s mother and Nero’s wife, respectively), and those of other figures. Neither the remains of Augustus’ only natural daughter, Julia Major, nor those of his daughter, Julia Minor, both of whom were accused of adultery and exiled by the prince, were received there. Being buried within the Mausoleum represented, therefore, an acknowledgement of power or association with power; being excluded from it, on the other hand, constituted a powerful act of moral and/or political condemnation.

The propagandistic intentions with which the tomb was erected must have been evident early on. The marble blocks covering the structure were covered, over the years, with inscriptions celebrating the lives of the deceased received there: the Mausoleum recounted the exploits of a lineage, communicating with its subjects, and stood as a de facto public memorial to many, new summi viri.

|

| Roman art, Augustus of Prima Porta also known as Augustus Loricate (1st century AD; marble, height 204 cm; Vatican City, Vatican Museums). Ph. Credit Till Niermann |

|

| Reconstruction of the original appearance of Augustus’ mausoleum according to Paola Virgili (archaeologist) and Alberto Mancini (architect) |

|

| TIM Foundation’s reconstruction |

|

| The obelisk of Santa Maria Maggiore. Ph. Credit Martin Knopp |

|

| The obelisk of the Quirinal Palace. Ph. Credit Wolfgang Moroder |

And staying on the subject of propaganda, even with a big leap forward in centuries, in light of what was said earlier about the historical figure of Augustus, it is understandable what were the reasons on the strength of which this character was so dear to fascism. The image of the father of the Roman empire, glorified as a peacemaker and at the same time a powerful ruler, was to be used in order to effectively glorify the new regime and especially its leader, the creator of a new empire, establishing a relationship of continuity between one and the other, as forerunner and worthy successor. In 1937, as soon as the celebrations for the bimillenary of Augustus’ birth began, at the inauguration of the Augustan Exhibition of Romanity set up in the Palazzo delle Esposizioni, archaeologist Giulio Quirino Giglioli, director of the event, called Mussolini “the new Augustus of the resurrected imperial Italy.” A propaganda project, then, that represented a key step in the larger one aimed at Fascism’s appropriation of Rome’s ancient history.

Already at the end of 1925, Mussolini, in a speech delivered on the Capitol, addressing the new Governor of Rome, Filippo Cremonesi, stated, “You will continue to free the trunk of the great oak tree from everything around it that adorns it. You will make way around the Augusteum, the Theater of Marcellus, the Capitol, the Pantheon. Everything that grew around it in the centuries of decadence must disappear. [...] The millennia-old monuments of our history must giantise in the necessary solitude.” .

Since 1924 demolition had begun on the buildings that covered the Markets of Trajan, the Forum of Augustus and that of Caesar, then it had been the turn of work in the area of what is now Piazza di Torre Argentina, the Theater of Marcellus and later the dismantling of the medieval quarters that had sprung up to the right of the Altar of the Fatherland. In 1931 work had begun on perhaps the best known intervention: the destruction of the Alessandrino quarter and the opening of Via dell’Impero.

All this moved, clearly, from the conviction that the medieval remains, and more generally the elements not belonging to the Roman phase, had no historical value and that it was useless to preserve them. To the governor of Rome, who had reported to him the doubts of the historian and former minister of education Pietro Fedele about the demolition of all that remained of the popular urbanism of medieval Rome, and in particular the elimination of some of the houses behind the church of San Nicola in Carcere, Mussolini in 1931 had replied with a lapidary note: “Continue demolishing and if necessary we will also demolish the melancholies of Senator Fedele, who is ridiculously moved by a pile of latrines.”

The intention to exalt the architecture most useful for propaganda was combined with the aspiration to create a modern city, a metropolis that looked to the future and was demonstrated by the power of the regime: a new Fascist Rome capable of renewing the glories of the ancient city.

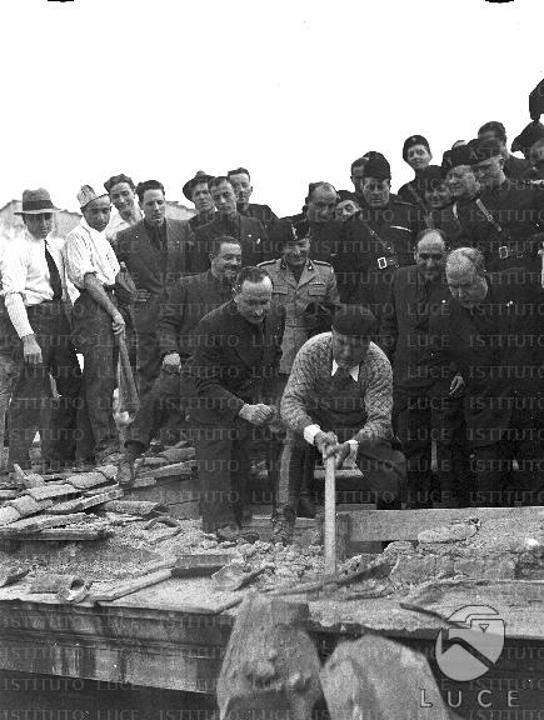

Giving the first pickaxe to inaugurate the demolitions around the Mausoleum of Augustus, on October 22, 1934, Mussolini declared, “the works for the isolation of the Augusteum to which I today give the start and which must be completed within three years for the bimillenary of Augustus have a triple utility: that of history and beauty, that of traffic, that of hygiene. [...] Even the isolation of the Augusteum, with the creation of a large square and a wide gateway to Corso Umberto I will be of great benefit to urban traffic. As was the case with Via dell’Impero where 25 to 30 thousand motor vehicles pass through in 24 hours. So these are not purely archaeological arteries.”

So fascism celebrated with great emphasis the bimillenary of Augustus’ birth between September 23, 1937, and the same date in 1938. The anniversary was celebrated with exhibitions, conferences and inaugurations, and in view of this event, both the mausoleum and theAra Pacis were the object of great attention by the regime already in the preceding years.

In 1926, and up to 1930, the first scientific excavations were conducted in the underground rooms of the tomb, under the direction of the aforementioned Ciglioli and Angelo Maria Colini, with the aim of making the burial place of Augustus accessible again, after centuries of reuse of the building that had been transformed, as we shall see better later, into a fortress, garden, amphitheater, theater and concert hall.

During the aforementioned investigations, the commemorative epigraphs of Emperor Nerva, Octavia and her son Marcellus were found, and useful documentation could be collected to understand more accurately what the original layout of the building had been. Already at this juncture, moreover, it became unequivocally clear to all participants just how bad the monument’s state of preservation was.

The 1931 Master Plan (making up for what had already been partially provided for by the 1909 Plan and the 1925-1926 Variant, both of which were disregarded) definitively established the demolition of the entire surrounding neighborhood that had sprung up since the Renaissance period, about 120 buildings arranged over 28,000 square meters. In the same years, the Correa Palace, located north of the tomb, and the structures of the Auditorium that had been built on the ancient complex and was an important gathering place and stimulus for the city’s cultural life were also dismantled. The last concert was held there on May 13, 1936.

|

| The area of the Mausoleum of Augustus from above before the demolitions of the 1930s |

|

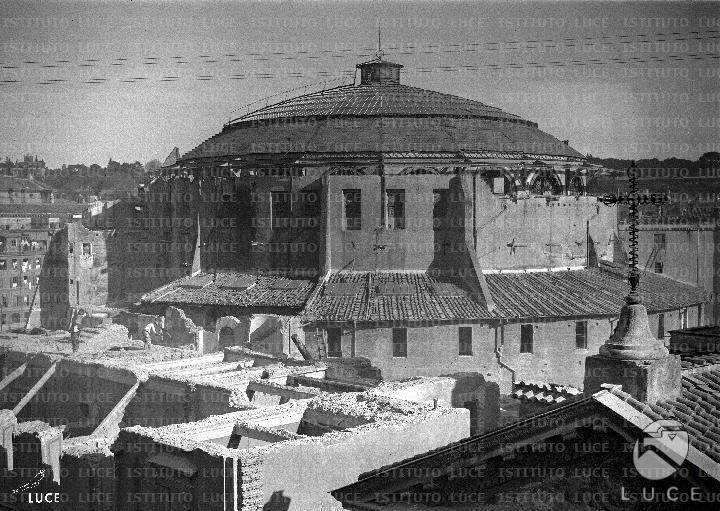

| Benito Mussolini picks up a building on Via di Ripetta (October 1934). Ph. Istituto Luce |

|

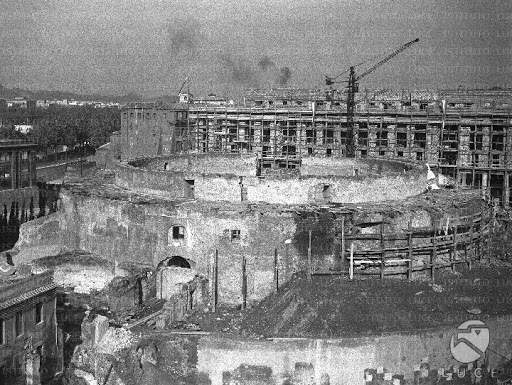

| The Mausoleum during the uncovering works of the 1930s |

|

| Construction work on Piazza Augusto Imperatore around the Mausoleum. Ph. Museum of Rome Archives |

|

| The emergence of Augustus Emperor Square and the INPS buildings. |

As mentioned demolitions began in the fall of 1934, and continued intensively for years. Once “liberated,” the monument underwent further excavation and restoration, which mainly involved the largely buried exterior walls.

However, given the conditions in which the structure was in, the concrete result of all this could only be very different from expectations: for the remains brought to light, which were moreover found 7 meters below the floor of the modern city, was soon coined the unflattering nickname of “carious tooth” to remark the deep state of degradation of the complex, proven by the spoliation and various forms of reuse to which it had been subjected.

Among the proposals for the arrangement of the Mausoleum should be noted the one put forward by architect Adalberto Libera, who suggested making the crypt a shrine dedicated to the campaign in East Africa: a room lit by candelabra with a statue of Augustus in the center and the names of the fallen reported on the walls in bronze characters. The idea, however, was not accepted. They opted for a simple ruin-like arrangement of the building, with partial covering by evergreen vegetation, as proposed by art historian and architect AntonioMuñoz.

The initial design for the plaza resulting from the demolitions, presented in 1935 by architect Vittorio Ballio Morpurgo, envisioned a space enclosed by buildings on all four sides, with the main perspective on the monument from Via del Corso through a V-shaped entrance to the plaza. Two avant-corridors to the south would flank the steps leading up to the Mausoleum, as well as house a museum containing archaeological finds recovered in the area during excavations. In addition, a portico was planned to encircle the Mausoleum below, at the archaeological level. But the program did not convince Mussolini, who radically altered it, eliminating the aforementioned colonnade, the museum forebays and some buildings to the west in order to bring the Mausoleum closer to the river. The square, therefore, assumed a U-shape with a main perspective on the Mausoleum from the Lungotevere.

In his later conception Morpurgo replaced the outcrops with an underground museum, later not realized, designed to house the reconstruction of theAra Pacis; later he proposed instead to place the altar in a shrine in front of the entrance to the imperial crypt. In both cases, therefore, the architect expressed the conviction that the two monuments should be placed in close proximity.

In 1937 work was completed on the recovery of theAltar, which had begun in the early twentieth century. The work had been traced almost eight meters below street level, buried under Palazzo Fiano in Piazza di San Lorenzo in Lucina. The regime’s desire to present the reconstructed monument to the public by the end of the celebrations for the two thousand years since the birth of Augustus imposed a rather hasty reassembly of the fragments, which did not fail to arouse numerous doubts among scholars in the years that followed.

The choice of the location in which to relocate it ( in situ rearrangement was not considered feasible because it would have involved the destruction of the Palace above it) was crucial, given the importance such a work had for the regime. Mention has been made of the role assigned to the founder of the Empire in fascist propaganda: with its allegorical depictions of a powerful, prosperous and pacified civilization under Augustus, theAra Pacis was perfectly suited to magnify the image and politics of the Duce, associated with those of the Roman prince.

The initial proposals for the placement of the altar, therefore, were: those of Morpurgo mentioned above, placement at the Baths Museum, and installation along Via dell’Impero. Later again Morpurgo came back to suggest placing the monument still at the Mausoleum, but at modern street level.

In the end, it was decided to place theAltar on Via di Ripetta, inside a pavilion that would allow it to be viewed from the outside as well, encouraging its dialogue with both the river and the Mausoleum.

In less than a year and a half, the monument had to be reconstructed and the container, also designed by Morpurgo, had to be built. Thus on September 23, 1938, theAra Pacis in its new arrangement could be solemnly inaugurated, inside the shrine, which, despite the controversy related to the aesthetic issue but especially despite its inability to guarantee the proper preservation of the altar, remained there until the intervention of the U.S. architect Richard Meier in the early 2000s, which was also far from free of controversy. If, however, with the altar the work had managed to be finished by the bimillenary deadline, the same did not happen with the Mausoleum, whose restoration, as of September 23, had been finished only on the side facing theAltar. The war, of course, caused the interruption of work on the building, which resumed only in 1952, with the construction of retaining walls and stairs to the archaeological level.

|

| The Ara Pacis. Ph. Credit |

|

| Morpurgo’s display case of the Ara Pacis (after restoration in the 1970s). Ph. Credit |

|

| The shrine of Meier’s Ara Pacis |

So, the regime made the Mausoleum the heart of what was supposed to be a new historical-mythological center of Rome, eliminating as much as possible all traces of what, over the centuries, had been built next to and beside the monument. This was yet another metamorphosis known by the Mausoleum, which up to that time had represented one of the most eloquent examples of the perennial change of Rome and its millennial stratification, of which, fortunately, some examples have been recovered today in different points of the complex where materials referable to different historical phases have been found during recent investigations.

Already during the imperial period, the architectural isolation of the Mausoleum gradually diminished, due to the construction of a number of buildings of which traces have been found in the various excavations in the vicinity of the site. The fall of the Roman Empire was followed for the tomb by a long period of abandonment, resulting from the interruption of routine maintenance.

There is no further news of the Mausoleum until 952, when a diploma of Pope Agapitus II mentions a small church named Sant’Angelo de Agosto, positioned on top of the mound, in cacumine; however, the exact period when the place of worship arose remains unknown. Having ceased all use of the building, it had become overgrown with vegetation, turning into a wooded knoll, on top of which the church was built.

In the 12th century the remains of the Mausoleum were adapted as a fortress by the powerful Colonna family. At the structure, in 1354, the burning of the body of tribune Cola di Rienzo, who had been killed two days earlier on the Capitoline Hill, took place.

The greatest damage to the ancient building dates from the fifteenth century, the upper portion of which collapsed, evidently as a result of the systematic spoliation of the stone parts of which there are records. By the middle of the century, in fact, a number of lime kilns are attested in the vicinity of the Mausoleum, indicating intensive exploitation of the building as a quarry for materials. In the early 16th century the Mausoleum became the property of the Orsini family.

Baldassarre Peruzzi and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger are credited with the first archaeological exploration of the building, carried out in 1519, during work on the construction of the hospital of San Rocco and the opening of the Via Leonina. On this occasion Peruzzi produced a large series of drawings that still constitute a fundamental documentary source today. Among other things, the artist had the opportunity to observe the two Egyptian obelisks, which, however, as already mentioned, would be raised only later, centuries apart.

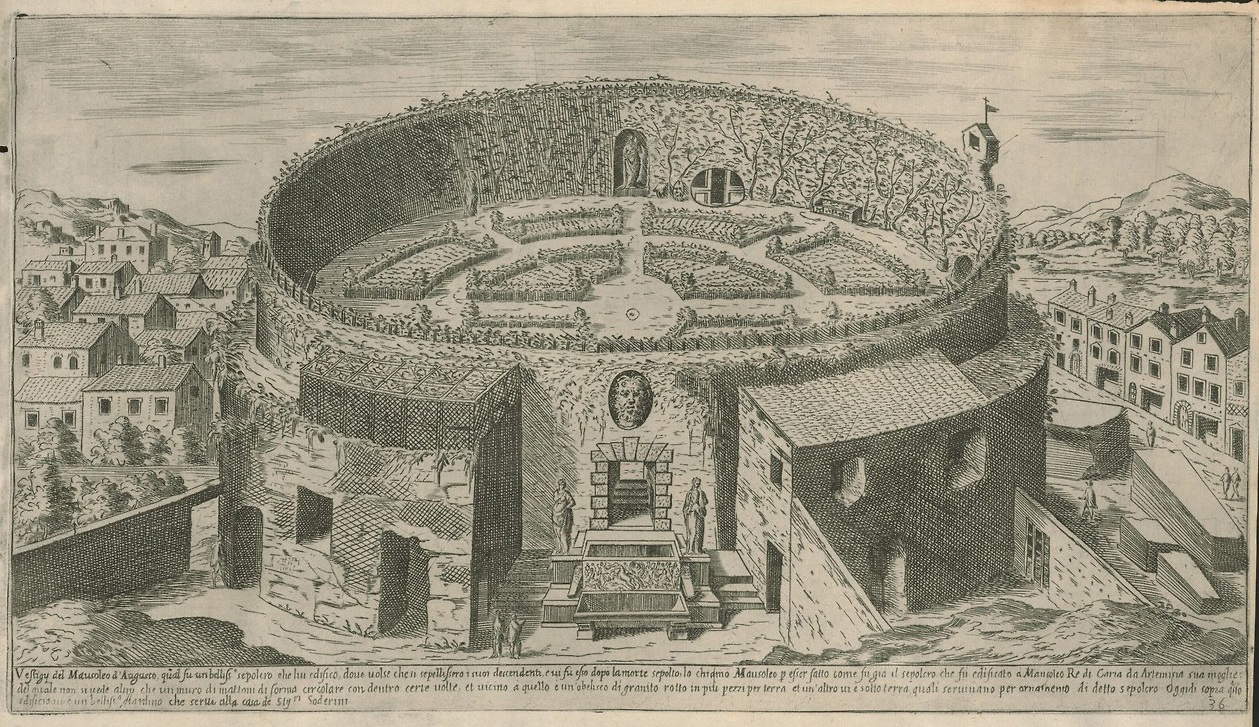

From this time there began to spread among artists and humanists a great interest in the ancient monument, which became the subject of numerous studies. There were many, moreover, who reproduced it in drawings, prints and paintings; among them Raphael, who in the fresco depicting the Vision of the Cross of Constantine in the Vatican Stanze, executed between 1520 and 1524, inserted the Mausoleum in the background, imagining what its ancient appearance should have been.

In 1546 the tomb passed to Monsignor Francesco Soderini, a member of a noble family of Florentine origin, who also obtained, from Paul III, permission to excavate around the building to recover ancient material to acquire in his own collection, but also to level the ancient structures. In fact, in the central part of the Mausoleum, which had already been reduced to a sort of circular basin due to the mentioned collapse, Soderini implanted an Italian garden, embellished with statues and sarcophagi, adjacent to the noble palace that was instead built north of the tomb. Moreover, the setting up of private gardens having scenic ruins as a backdrop and conceived as a display place for one’s collections of antiquities was a rather widespread practice in Rome in those years among the wealthiest families. One example above all is the Horti Farnesiani, created at the behest of Cardinal Alessandro Farnese starting in 1537.

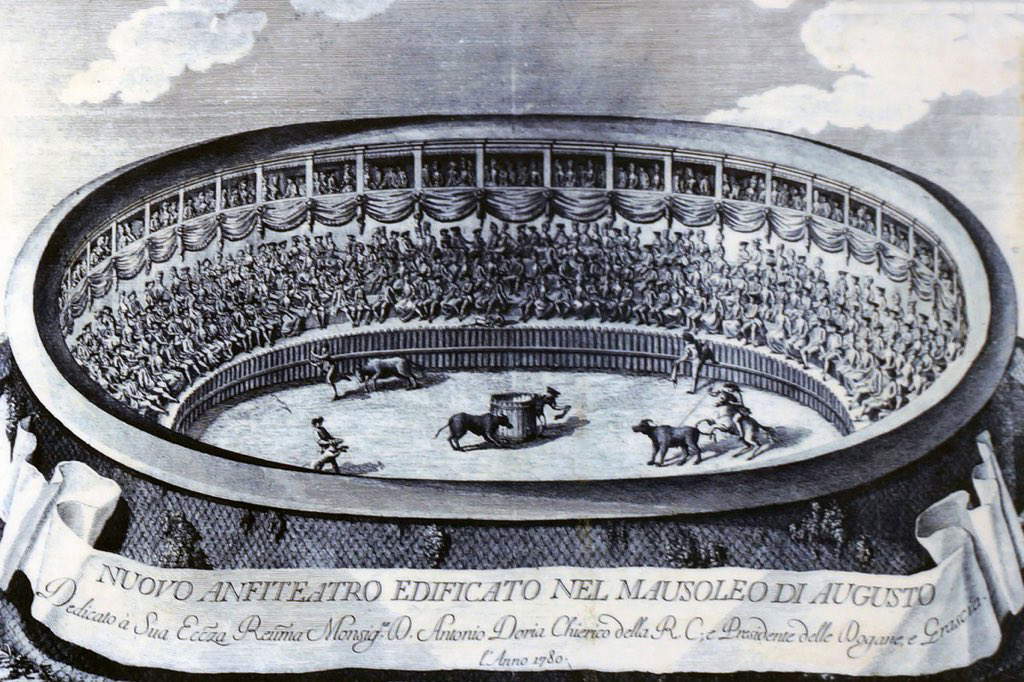

After several changes of ownership, in 1700 the Mausoleum passed to the Marquises Correa, a family of Portuguese origin. Decades later the Spaniard Bernardo Matas, who was renting part of the property which he used as an inn, transformed the circular garden space into an arena, encircling it with wooden tiers, and organized bull and buffalo fights there. Thus was born theCorrea Amphitheater, which three years later was taken over directly by the same family of owners. The Correas carried on what Matas had started, adding other activities such as the sack race or the game of cuccagna, in the afternoon, and shows with fireworks, the fochetti, in the evening.

In the late 1780s, a new owner, Marquis Vivaldi Armentieri, seeing the large number of spectators, decided to build a stable brick amphitheater, later purchased in, 1802, by the Apostolic Chamber.

Stendhal, in his Roman Walks, published in 1829, gives us a concise but effective account of the success of the shows at Correa:“on Sundays the people go to see the tauromachiae at the Mausoleum of Augustus, and the foreigners go to see the people.” The increasingly spectacular evening firesides, on the other hand, attract an audience consisting of high prelates and other aristocrats. The facility is also used for official events, such as the festivities organized for the triumphal entry of Francis I of Austria in 1819.

In later years, first the bull jousts and then the firesides were abolished due to security concerns, and replaced with theatrical performances, musical concerts, and circus games.

With Rome becoming the capital, the building returned to private hands: it was bought by Count Giuseppe Telfener, took the name Politeama Umberto I, and became a theater. In 1880 Telfner transformed the structure in an eclectic, neo-medieval style with a new glass roof supported by metal structures. Shortly thereafter the theater was temporarily closed due to the absence of fire exits, to build them, however, the Archaeological Commission did not provide permits for reasons of protection of ancient structures. This resulted in a long dispute with the State Property Office, which ended up buying back the theater, then making it available to sculptor Ettore Chiaradia, who modeled there the bronze statue of Victor Emmanuel II made for the Altar of the Fatherland.

In 1907 the building was given to the Municipality of Rome, was adapted to safety standards with the excavation of the ancient entrance, transformed into an Auditorium, and renamed “Augusteo.” From the following year the first season of symphony concerts by the Accademia di Santa Cecilia began.

|

| Etienne Du Pérac, Vestigi del Mausoleo di Augusto, from I vestigi dellantichità di Roma raccolte et ritratti in perspettiva (1600) |

|

| Print from 1780 with a depiction of the amphitheater Correa |

|

| The Mausoleum transformed into an Auditorium. Ph. Istituto Luce |

|

| The Mausoleum transformed into Auditorium, interior |

|

| The Mausoleum transformed into Auditorium, interior. Ph. Istituto Luce |

As mentioned above, this happy moment of the Auditorium, inside which the most prestigious musicians, singers and conductors performed, lasted until 1936, while already by the 1920s the Mausoleum aroused the ’interest of the regime, which ended up irreversibly changing its appearance and functions.

We come, in conclusion, to the present day. Since 2007, the monument has been the subject of a 12-year-long conservative restoration, carried out with the economic intervention of Roma Capitale and MiBACT, all aimed at a musealization work financed by the TIM Foundation, and directed by the Capitoline Superintendence for Cultural Heritage, to make usable a complete museum itinerary aimed at illustrating the various historical phases of the Mausoleum, also offering, after April 21, 2021, digital content in visual and augmented reality. At the same time, since May 2020, work has been started (with a huge delay compared to the original plan, which envisaged the completion of the work on the Mausoleum and the Square, initially planned in the context of a single project path, by 2014) on the urban arrangement of the square based on a project by architect Francesco Cellini.

After a decidedly long period of time, therefore, the Mausoleum is returning to be visited, at least in the central area, by visitors, who will be able to access it free of charge until April 21, the date of Christmas in Rome. Thereafter, throughout the rest of the year, free admission will be reserved only for residents of the capital. What the ticket cost will be for everyone else is still a mystery, and besides, reservations for days after April 21 (by that date it is already sold out) are still not allowed.

One can only hope that this year’s reopening, as soon as the current limitations due to the pandemic are lifted, will mark the beginning of a new life for this vital archaeological site that can rededicate the memory of all the others to as wide a public as possible.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.