by Marco Tanzi , published on 02/05/2019

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

The formerly Hammond Madonna, which went to auction yesterday at Christie's and remained unsold, was attributed to Fra Bartolomeo: in the article, an unpublished proposal by Professor Marco Tanzi, professor of Modern Art History at the University of Salento.

It is probably because of the authority of the person who formulated the attribution (the late Everett Fahy, one of the sharpest and finest international connoisseurs since the 1960s) that no further verification was deemed necessary on the reference to Fra’ Bartolomeo of the Madonna and Child already in the collection of Geoffrey F. Hammond in Stamford, Connecticut, which went unsold on May 1 at Christie’s in New York (lot 28), where it had an auction base of $1.5 to $2.5 million. It is a dazzling panel transported on canvas measuring 88.3 x 68.3 cm, with a provenance that can be reconstructed from at least the late 19th century, and which has had in its brief critical history only two labels: that of Mariotto Albertinelli from 1905 until 1994, when Fahy shifted it to the name Fra’ Bartolomeo. Two years later, an articulate file by the Philadelphia scholar accompanied the painting in the exhibition devoted to Fra’ Bartolomeo and the School of San Marco, between Palazzo Pitti and the Museo di San Marco in Florence between April and July 1996.

|

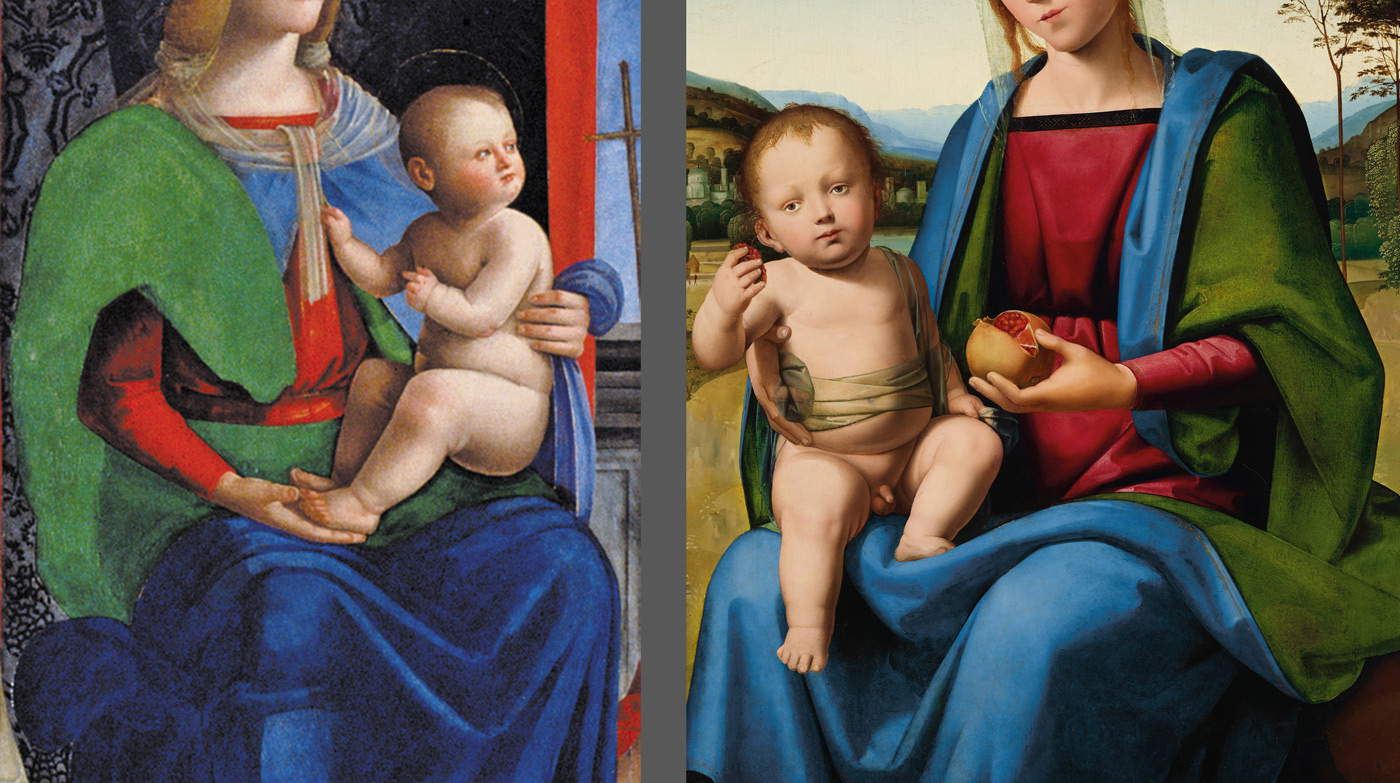

| Johannes Hispanus, Madonna and Child with a Pomegranate (formerly New York, Christies) |

In our very composite milieu I know quite a few people who enjoy, literally, when they can disprove an attribution by Federico Zeri; let alone if it is a report provided by Roberto Longhi or some other member of the narrow elite of the truly great connoisseurs. Without wishing to sound too modest (for I never was) I have always seen this from another perspective, that is, it has always seemed to me a great satisfaction to be able to see that my opinion sometimes coincided with that of the masters. I confess, therefore, to feeling great embarrassment now that I have to correct such an authoritative attribution as Everett Fahy’s for the Madonna at auction at Christie’s. This is also because Everett (of whom I cannot consider myself a friend in the strict sense of the word only because of the few acquaintances I have had) has always been with me of a very unique and extraordinary cuteness and generosity: there was a time, at the turn of the millennium, when we wrote to each other often (he also sent me postcards, never trivial, always excellently chosen) and gave me important suggestions for my research, sending me from New York several photographs (hard copy, I emphasize: something of which every art historian is usually most jealous) that I hastened to return to him as soon as I had used them. A scholar and a person of whom I had the highest esteem and sympathy, and I retain a beautiful memory.

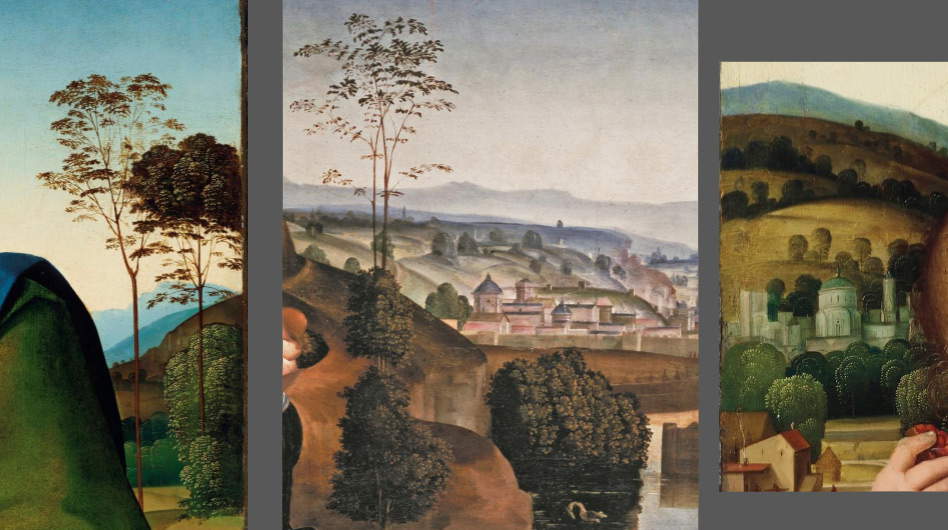

We come to today. I jolted in surprise, leafing through the auction catalog, to see the Madonna excellently reproduced, whereas in the 1996 exhibition catalog the image was reversed and yellowish dominant, with two details of the landscape and the pertinent comparisons, at the time instituted by Everett, with the Holy Family in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (formerly Panciatichi, later Contini Bonacossi) and the VolterraAnnunciation. The landscape, first of all, so trivialized in its rendering of foliage and architecture, seemed to me awkward for a painter of the friar’s level, while such a simplified and as if metallic manner of drapery has little to do with those that punctuate his production (see also, for example, the remarkable preparatory drawing for the angel of the Volterra panel, in the Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi, inv. 512 E), hints at models further north in the Apennines: a drapery, to put it mildly, à la Boccaccio Boccaccino the younger (that of theAdoration of the Shepherds in the Galleria Estense in Modena) or, si parva licet, à la Boltraffio. I had Christie’s send me the very high-definition file of the Madonna and downloaded from the Internet that of the Los Angeles painting so that I could examine the two works face-to-face, with the utmost ease: the Holy Family shows a state of preservation that suffers greatly from vigorous spullying (and indeed the canvas is “Not currently on public view” in the museum’s halls) that does not, however, prevent one from discerning an extremely worn original by Baccio. And, perhaps (but this judgment is probably dictated precisely by the painting’s current state), not even among the most beautiful, once its earliest critical history is reread and, in particular, where compared precisely with the figure of the Virgin in the stunning 1497 Annunciation in Volterra Cathedral, which (along with the rendering of the landscape in the center) speaks a different and far more refined language. The Child in the arms of the Madonna just passed at auction is a slavish quotation of the one now at LACMA, but the pictorial definition of the two works is not the same: in the canvas formerly Contini Bonacossi, despite its bumpy condition, one can first of all grasp a softness in the backlight and chiaroscuro passages that is missing in our painting, in which, rather, a sharpness of planes and a much less delicate way of giving the lume is evident, in search of a sharper and more contrasted effect. The Virgin’s face has the texture of those of certain biscuit porcelain dolls, which almost give the impression of being as if annihilated by a uniform layer of powder; while the eyes and mouth are made with a sharp, short cut.

|

| Fra Bartolomeo, Holy Family (Los Angeles, Los Angeles County Museum of Art). |

Let us return to Fra Bartolomeo’s landscapes; Roberto Longhi in 1926 uses precisely that of theAnnunciation to corroborate the attribution to the friar of theAdoration of the Child at the Borghese Gallery: in both we see “The same dappled plains now as of marshes, now of shade brought by the volumes of trees, inhabited by buildings, often poetically ruined, of castles, mills, and bridges, flanked by cleavages at once cleared; entrovi a diffuse for all foreign scent either in the form of the cities, or in the northern cobalt of the last mountainous remoteness, or finally in the way the foliage aluminizes.”

Now, can such a truthful and evocative reading be adapted to the conventional and somewhat dumbed-down backdrop of the Madonna already Hammond? I would say no. Instead, similar formal abbreviations are found, in equal measure, in the works of a painter I know quite well for having had a small exhibition there some 20 years ago and for having later entrusted it to the care of a good student of mine, Stefania Castellana, who devoted her doctoral thesis to it, from which she then drew, a couple of years ago, an excellent monograph: Johannes Hispanus, the wandering “Spanish” John who, between the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, travels around Italy from Rome to the Veneto, from Tuscany to Lombardy, from Emilia to the Marches, where he finally finds a landing place to his long wanderings.

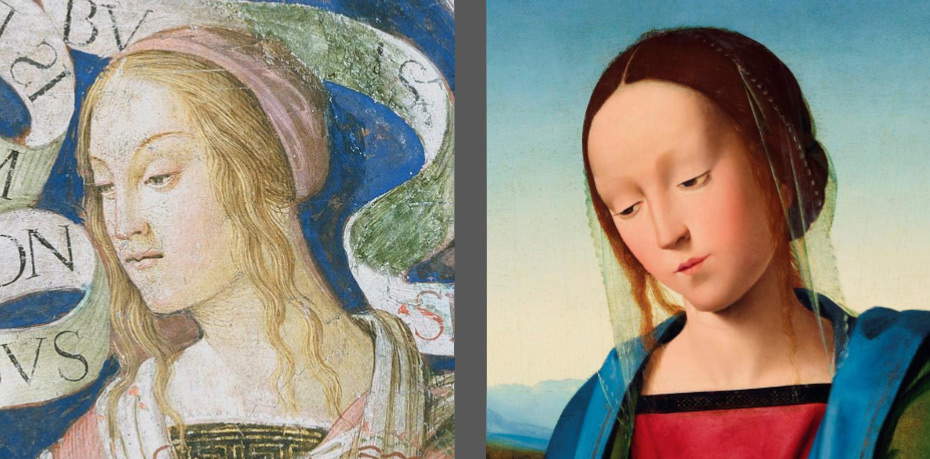

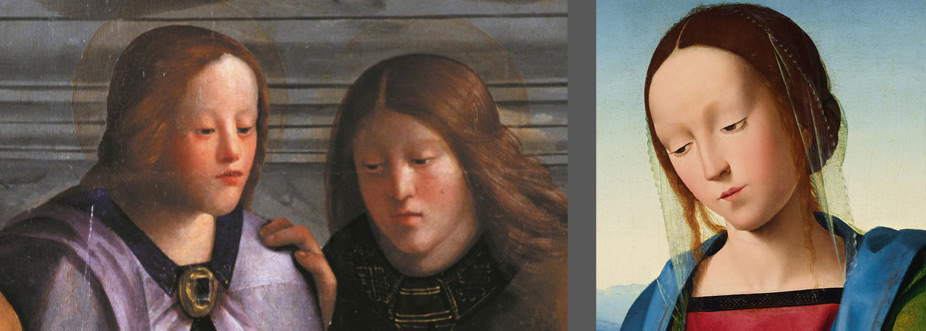

To Johannes’s Florentine period (or to the moment immediately following, as it were, “along the Romea,” toward Venice) belongs, in fact, the Madonna just passed by Christie’s: the relationships with Fra Bartolomeo are undeniable, but also those with Piero di Cosimo (already noted, at the time, by Venturi senior), Perugino and with the galaxy of painters gravitating to Florence in the last decade of the fifteenth century. There are numerous works for comparison: from the Madonna and Child with Two Angels formerly Finch, in a private collection, to the Tondo Chigi(Madonna and Child with Two Angels), also private, to the other tondo in the castle of the Counts Guidi at Poppi(Madonna and Child between Saints Catherine and Mary Magdalene). Above all, however, our painting is to be closely related to the two splendid espaliers passed at Sotheby’s in London on July 4, 2018 (lot 46) with the Stories of Achilles that I had published in 2000 thanks precisely to Everett, who had so generously pointed them out to me. And how much then, of the incised and somewhat scalene features of the Virgin’s face, is to be found in that of the Erythraean Sibyl frescoed in a lunette in the Hall of the Sibyls in the Borgia Apartments in the Vatican, returned to the Spaniard by Stefania; or, again, in the drapery (partly ruined, unfortunately) and in the faces of the angels at the foot of the throne of the Viadana altarpiece, executed most likely during his Venetian sojourn.

In this case, then, it was precisely the outcome of the auction that did some justice: I now leave it to Stefania Castellana to sort out (in a dedicated, scientifically equipped essay) more precisely than I was able to do, thus, at the imprint, the chronology and placement of the painting in the all-curves-and-turns catalog of Johannes Hispanus.

|

| Johannes Hispanus, Madonna and Child with Two Angels (Madonna Finch), location unknown |

|

| Johannes Hispanus, Madonna Enthroned with Child between Saints James, Francis, John the Baptist, Magdalene, and three musician angels (Viadana, church of Santa Maria e San Cristoforo in Castello) |

|

| Johannes Hispanus, Madonna and Child with two angels (Tondo Chigi), location unknown |

|

| Johannes Hispanus, Eritrean Sibyl, detail (Vatican City, Vatican Museums, Borgia Apartments, Hall of the Sibyls) |

|

| Johannes Hispanus, Departure of Thetis and Achilles for Skyros, Achilles among the daughters of Lycomedes, location unknown |

|

| Comparison between the LACMA Madonna and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison between the Finch Madonna and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison between the Madonna of Viadana and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison of the Children of the Madonna Finch, the Madonna formerly Hammond and the Tondo Chigi |

|

| Comparison of the Sibyl and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison between the angels of the Viadana altarpiece and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison between the Departure of Thetis and Achilles for Scyrus and the Madonna formerly Hammond |

|

| Comparison between two landscape pieces of the Madonna formerly Hammond (on either side) and the Departure of Thetis and Achilles for Scyrus (center) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.