The Liber Maiolichinus, a 12th century codex recounting the exploits of the Pisans in the Balearic Islands

The University Library of Pisa preserves a true monument of the city’s history, the Liber maiolichinus de gestis Pisani populi, the oldest codex that has handed down to us the feat accomplished by the Pisans and Catalans between 1113 and 1115 against the Muslims in the Balearic Islands, hence the name of the volume (“Majorcan Book of the Deeds of the Pisan People”). It is a chronicle in Latin, most likely written between 1117 and 1125, detailing the military expedition that the Pisans, Catalans, Sardinians, and Occitanians undertook against the Muslim taifa of the Balearic Islands (the term taifa meant one of the many small states that the Islamists had established in Spain after the conquest).

The Pisans organized the expedition to exercise their sovereignty over the islands, granted to Pisa by Pope Gregory VI in 1085. The expedition, invoked by Archbishop Pietro Moriconi of Pisa, soon took on the character of a crusade against the infidels: the Christians, led by Moriconi himself, Raymond Berengar III of Barcelona, the Occitan Hugh II of Empúries, William V of Montpellier, Aimeric II of Narbonne, Raymond I of Baux, and the Sardinian nobleman Saltaro of Torres, obtained from Pope Paschal II the’authorization to send the fleet to the Balearic Islands, and they appeared before the islands with 300 Pisan and 120 Catalan and Occitan ships embarking an army capable of gathering aid from the various parts of Italy, Sardinia and Corsica. The enterprise started from Ibiza, which was conquered in June 1113, and then moved on to the siege of Palma de Mallorca, which lasted until April 1115, when the city fell, the population was enslaved and the Muslim regent of the taifa was brought to Pisa as a prisoner. It was a short-lived victory, however, since in 1116 the Almoravids recaptured the islands, but it still achieved the effect of wiping out Muslim piracy, another of the expedition’s goals.

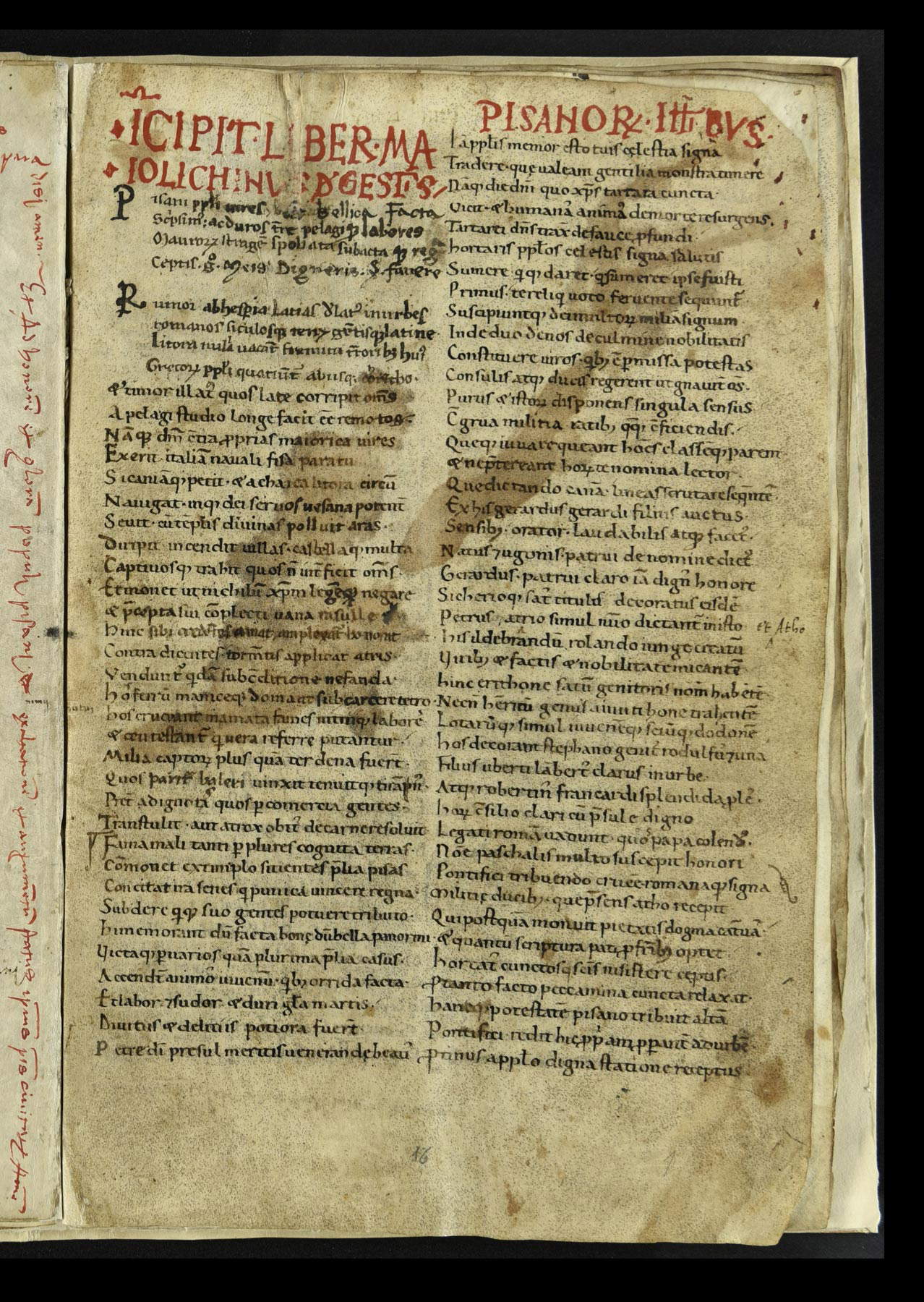

We do not know who the author of the Liber maiolichinus is, but it is possible, according to Paolo Tronci’s hypothesis, that the writing of the book could be attributed to a “chaplain of the Archbishopric,” given the prevalent ecclesiastical culture of the time in which it was written. The Liber is a poem composed of 3,544 hexameters divided into eight books that celebrate, with triumphalist accents, an event that, at the time of the codex’s creation, must have still been vivid in the memory of Pisa, evoking the enterprise with great and circumstantial realism. In fact, the poem collects the point of view of a Pisan citizen, satisfied with the military outcome, and moreover polemical with rival cities, particularly with regard to Lucca, which had withdrawn from the expedition, and Genoa, whose antagonism was already clearly emerging, and which like Lucca did not participate in the expedition, on the one hand because it considered it convenient for it to remain neutral, and on the other hand so as not to help the rival city.

The Liber is introduced by a brief proem in which the anonymous author invokes the support of Christ to sing the enterprise, explaining the reasons for the expedition, then proceeding with a singular and at least daring parallel between Pisa and Rome, with the Balearic Islands rising to the role of a new Carthage, and wishing that Pisa could retrace the splendor of Rome, at a ’era when the Tuscan city was experiencing a season of great splendor witnessed by the artistic construction sites in the Piazza del Duomo (the Cathedral was consecrated shortly after the Balearic expedition, in 1118). On a literary level, the author shows a mastery of ancient stylistics, transmitted by rhetorical precepts and transposed into modern expression, so much so that, while not a literary masterpiece, it can be considered “most notable as an indication of the strong love and tenacious preservation of classicism in Italy and its already sensitive renaissance,” as Carlo Calisse, who edited a printed edition, wrote in 1904.

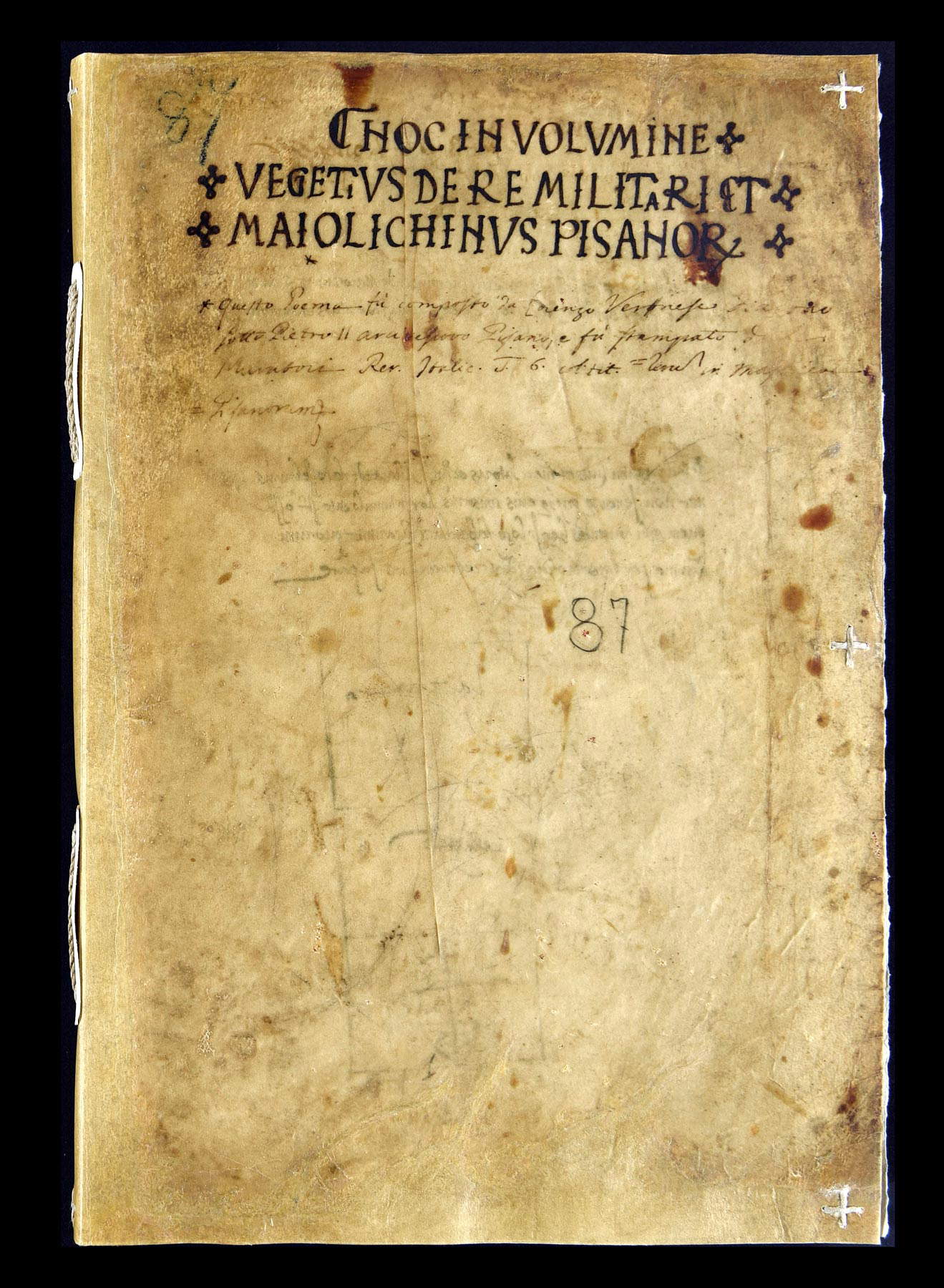

The codex owned by the Universitaria of Pisa is known as “P,” and is one of three extant copies of codices, along with that of the Laurentian Library in Florence, “R” and the British “B” preserved in the British Museum in London. Codex “P” was bound in the vellum cover of another work, Vegetius’ De re militari, to whose text it follows from paper 16 onward, and consists of 37 papers written on recto and verso in crisp caroline minuscule, a script that originated in the8th century but, because of its practicality and the speed with which it allowed manuscripts to be compiled, still in force in the 12th, unlike Vegetius’ work, which instead shows considerable alterations and evanescence. The binding was redone in the 19th-20th centuries.

The work was commissioned by the Municipality of Pisa and had a preeminently political purpose: in fact, it was the last product of the memorial strategy that the Pisanians pursued after the enterprise toward the two universal powers, that is, first toward the emperor Henry V, and then toward the popes Gelasius II, Callistus II and Honorius II. With regard to Henry V the Pisans pursued the goal of confirmation of certain public land concessions that the emperor wanted to recall under his authority along with those of Matilda of Canossa, who had died in 1115; in the case of the popes, on the other hand, the goal was the renewal, always questioned with each new pontificate, of the metropolitan privilege over Corsica that the bishop of Pisa had obtained in 1092 from Urban. The Liber Maiolichinus was thus crafted as an instrument of pressure from the Pisans toward Honorius II, which was to be accompanied by other persuasive actions, for example handouts of money, to convince the pope of the advisability of renewing the metropolitan privilege, against the opinion repeatedly expressed to the Curia by the Genoese. The goal was achieved, even with the war fought in 1119 between Genoa and Pisa.

The fortunes of the Liber maiolichinus had already waned by the fifteenth century, since at that time the Pisan notary Lorenzo de Sanctis scraped theincipit of paper 16 and rewrote it in capital script and red ink, adding above the second column the variant “Pisanorum illustribus” to the original “Pisani populi.” At that time the codex belonged to the noble Pisan Rosselmini family, as is evident from some notes found in the manuscript, and from them it passed in the 17th century to the Roncioni family, from which the state acquired the parchment collection and manuscript library in 1912. However, at that time the codex was already well known to scholars, especially following the “rediscovery” of Francesco Bonaini in 1844, who had exhumed it from oblivion after Muratori’s publication in his Rerum Italicarum scriptores. The Liber Maiolichinus was first studied as a primary historiographical source, given the multifaceted aspects of its contents (and then also because Calisse lamented the fact that no full-bodied historical sources survived of the Balearic expedition, so the Liber was an important tool for knowing the source of thatevent), finding the interest of a political historian such as Michele Amari in 1872, of law such as the aforementioned Carlo Calisse in 1904 and Gioacchino Volpe in 1906, and then of military, linguistic-literary and religious historians. The codex has also been studied in its own right, up to the present day, when in 2017 Enrico Pisano’s volume was published in the National Edition of Mediolatinian Texts, with an introduction and critical text by longtime scholar Giuseppe Scalia, a commentary by Alberto Bartola and a translation by Marco Guardo.

Finally, the Liber also retains an important international historical relevance: it is known in fact for the earliest known reference of " Catalans"(Catalanenses) as an ethnic group, and of “Catalonia” as their homeland, what makes it a true monument of Catalan identity, studied especially before Francoism and after its fall, celebrated in 1991 in an international conference entitled Liber Maiorichinus and 12th-century Mediterranean society, organized in Barcelona.

The University Library of Pisa

The University Library of Pisa was opened to the public in 1742 in the premises located under the Specola astronomica, on Via Santa Maria, currently the site of the Domus Galilaeana, and since 1823, following its only relocation, it has been housed in the fifteenth-century Sapienza building, of which it occupies the wings located northwest of the piano nobile, where the user rooms, reference rooms and offices are located, and the wings southwest of the second floor, used as book warehouses. The first book nucleus consisted of the private library of Professor Giuseppe Averani (1662-1738) received by testamentary disposition. In later years the original nucleus was increased by bequests, gifts from private individuals and professors, and the acquisition of the libraries of suppressed religious corporations. The purchase of about six thousand volumes belonging to the Florentine scholar Anton Francesco Gori of archaeological and antiquarian interest dates back to 1757. Then in 1771 numerous works of the Biblioteca Medicea-Palatine-Lotary Library were assigned to the Library at the behest of the Grand Duke. With the abolition of the Camaldolese Monastery of San Michele in Borgo, the manuscripts of Father Guido Grandi enriched its holdings, as did as did the precious incunabula from the monasteries of San Donnino and Santa Croce, which added to a number of Aldine editions such as Aristotle’sOpera omnia (1495-1498), Poliziano’sOpera omnia (1498), Thesaurus cornucopiae et Horti Adonidis (1496) and illustrated incunabula(Compilatio de astrorum scientia, Leopold of Austria, 1489).

Further eighteenth-century acquisition was the small but valuable collection of the Botanical Garden, while nineteenth-century important and valuable holdings include the manuscripts and drawings of Egyptologist Ippolito Rosellini (director of the library from 1835 to 1843), the numerous volumes acquired by testamentary disposition of University Provveditore Angelo Fabroni, the collection established at his own expense by Giuseppe Piazzini from 1820 to 1832, the period in which he held the direction of the library, the philological collection of Michele Ferrucci (director of the library from 1848 to 1881), the more recent scientific libraries of Filippo Corridi and Sebastiano Timpanaro, the medical collections of Diomede Buonamici and Antonio Feroci, the historical-literary collection of Professor Alessandro D’Ancona, and the library with the manuscripts of Count Franceschi. From the 20th century, Enrico Fermi’s dissertation on X-rays from 1922 is preserved in the University Theses collection, with those of Franco Rasetti and Nello Carrara.

Since 1975, the University Library of Pisa has been a state institute separate from the University, and is now an entity of the Ministry of Culture, while maintaining the task of “implementing coordination with the University in the forms deemed most appropriate in terms of services and acquisitions.” The institution currently has a holdings of more than 600,000 editions, 161 incunabula, 7,022 cinquecentine and 1,400 manuscripts.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.