The Liber Divinorum Operum: in Lucca the only illustrated codex of the work of Hildegard of Bingen

She is one of the central figures of 12th-century theology and, along with Teresa of Ávila, Catherine of Siena and Teresa of Lisieux, is one of only four women to be listed among the Doctors of the Church: she is Hildegard of Bingen (Bermershein von der Höhe, 1098 - Bingen am Rhein, 1179), a German nun and mystic, canonized in 2012 by Benedict XVI, and also a prominent figure in the culture of her time, since she was a poet, playwright, musician, linguist, and a lover of natural sciences, so much so that she even wrote a book on the nature of living things. Her theological vision, however, is encapsulated in three books: the Scivias, finished in 1151, in which three topics (creation, sin, and redemption) are addressed; the Liber vitae meritorum of 1158 devoted to the conflict between Good and Evil, God and Satan, and Vice and Virtue; and the Liber divinorum operum of 1174: the latter is a fundamental book for understanding Hildegard’s idea of the universe, which she considered, scholar Giulio Piacentini has summarized, “a complex reality, created, governed and ordered by Wisdom and God’s providential love, which give it harmony.” There are only three codices in the world today that bear witness to the Liber divinorum operum, and the only illuminated one is the 1942 manuscript in the State Library of Lucca.

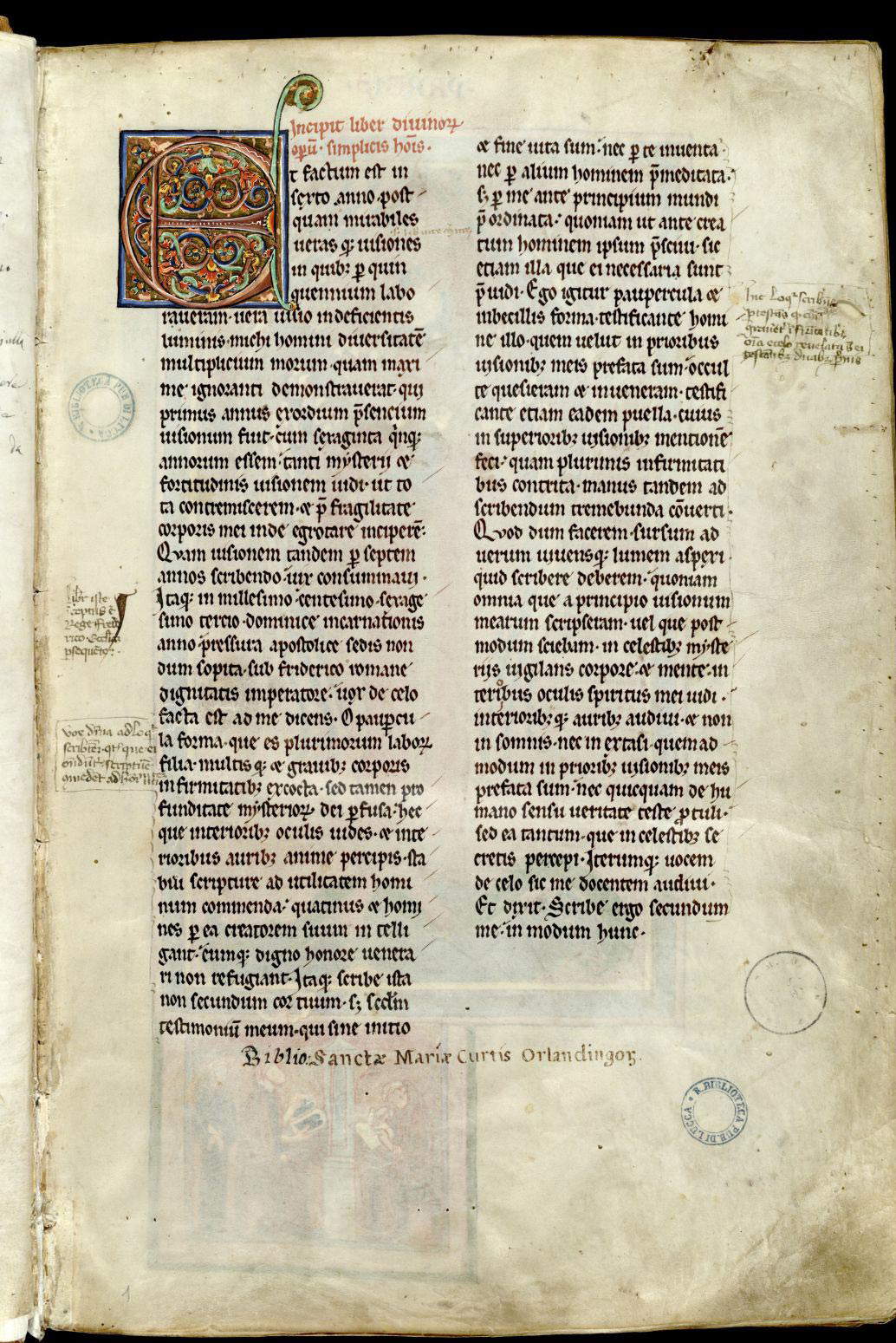

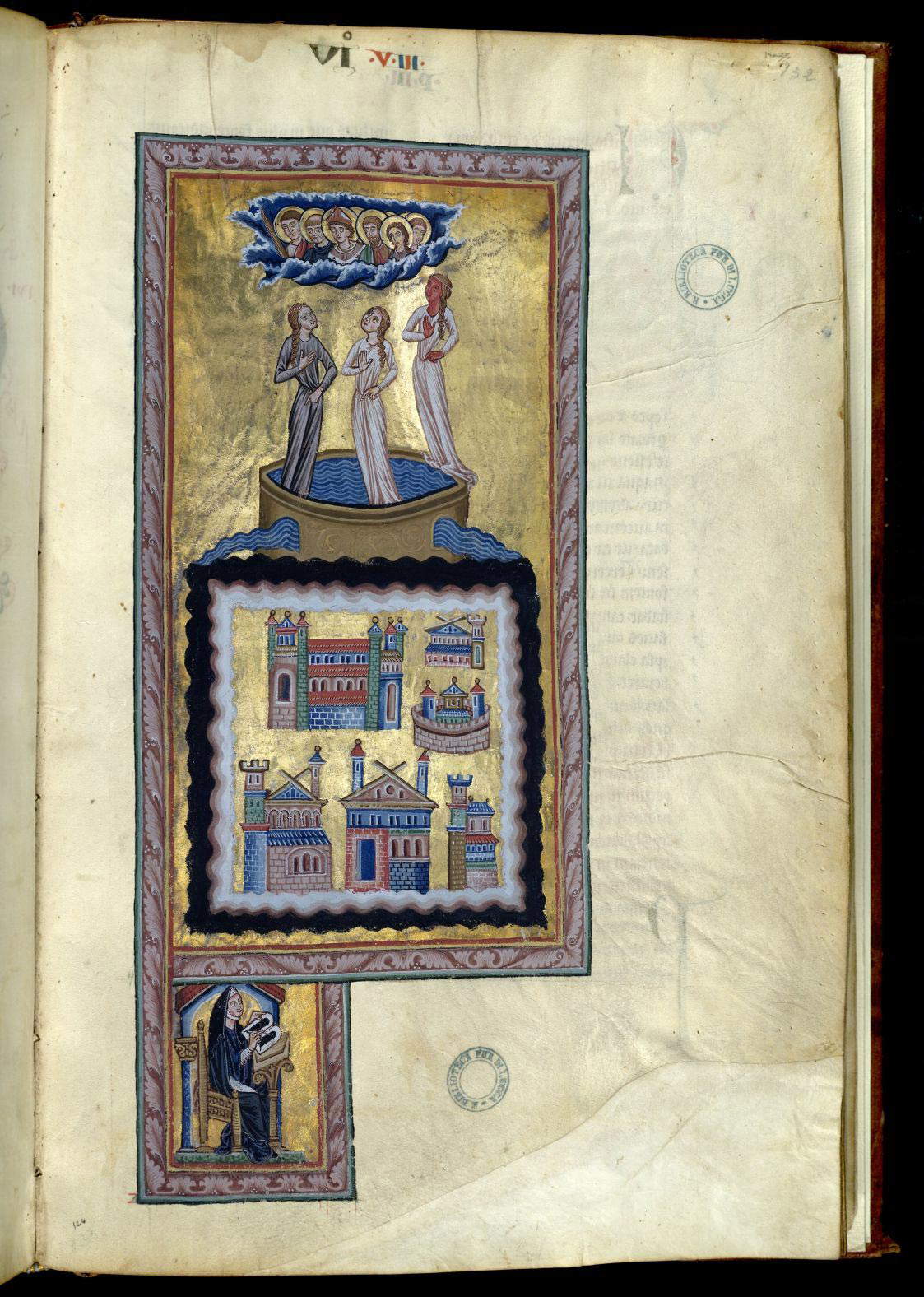

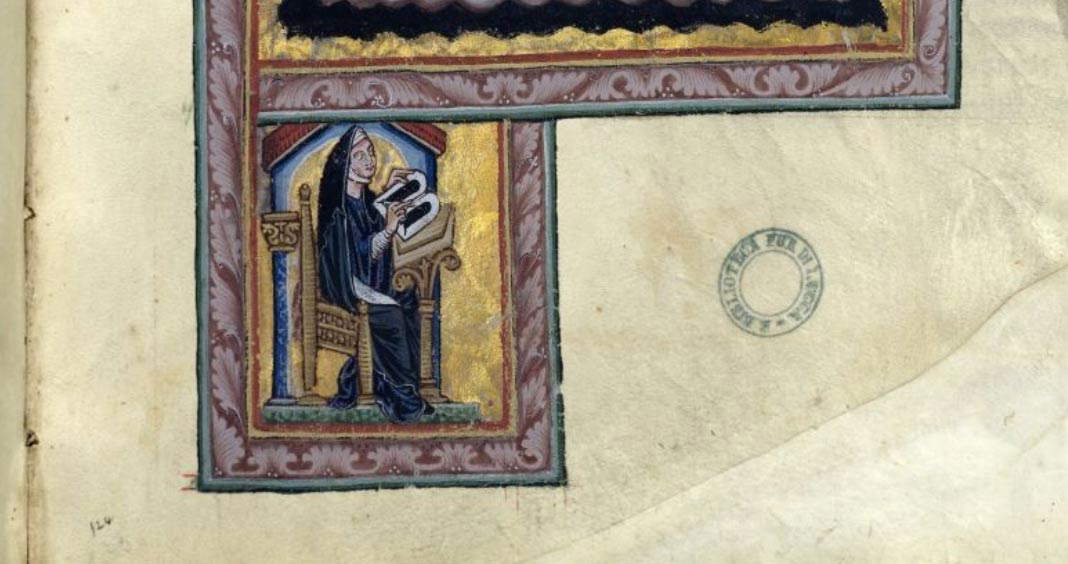

The Lucca codex comes from the Library of the Convent of the Clerics Regular of the Mother of God of Lucca: in fact, on the first paper of the volume appears the manuscript note attesting to this provenance, and the relevant stamp (later in 1877, when the convent was suppressed, the State Library of Lucca forfeited its library holdings). The manuscript was composed in the first half of the 13th century (between the second and third decade, to be exact), probably in a Rhenish scriptorium, and is written in Gothic script, in two columns of 38 lines each, with rulings traced in dry type. The titles, summaries, incipits and explicits of Hildegard’s various visions (the topics are in fact divided into visions) are in red ink, the capilettera are in red and blue and are undermined with plant motifs: scroll-like racemes that are sometimes intertwined with animal and human figures. There are also ten full-page miniatures, which have been attributed to a miniaturist of Rhenish cultural background. The codex also appears annotated by several hands and with a double numbering, an ancient and a modern one that coincides with the ancient one up to paper 108.

Giovanni Domenico Mansi (Lucca, 1692 - 1769), archbishop of Lucca, contributed greatly to the collection of the Library of the Convent of the Clerics Regular of the Mother of God, but we do not know when the manuscript with the Liber divinorum operum entered the collection. This is a very valuable specimen, denoting considerable care in the choice of material, editing, writing and illustrative apparatus. All these elements reasonably suggest that the 1942 manuscript was intended not for private devotion, but for study.

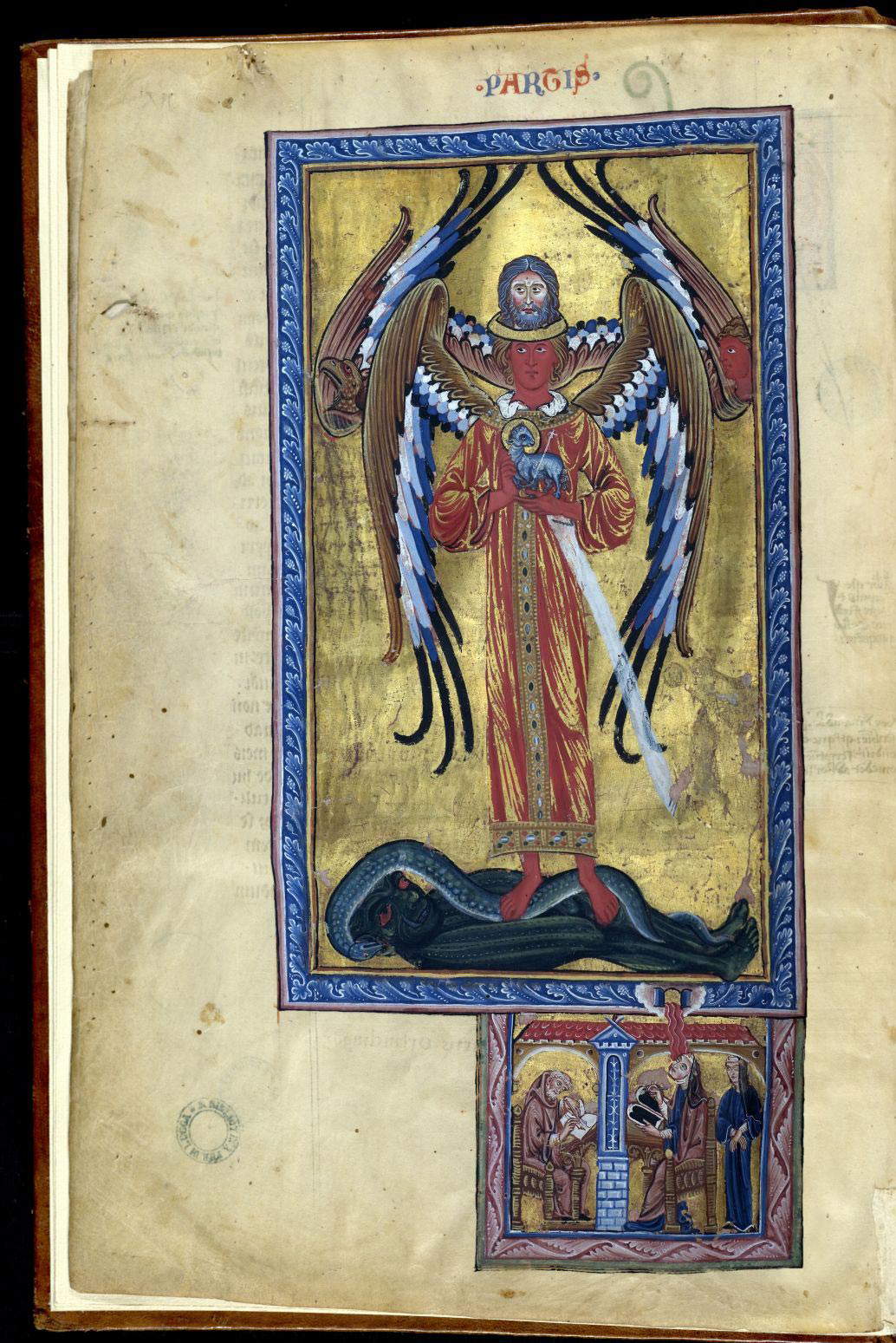

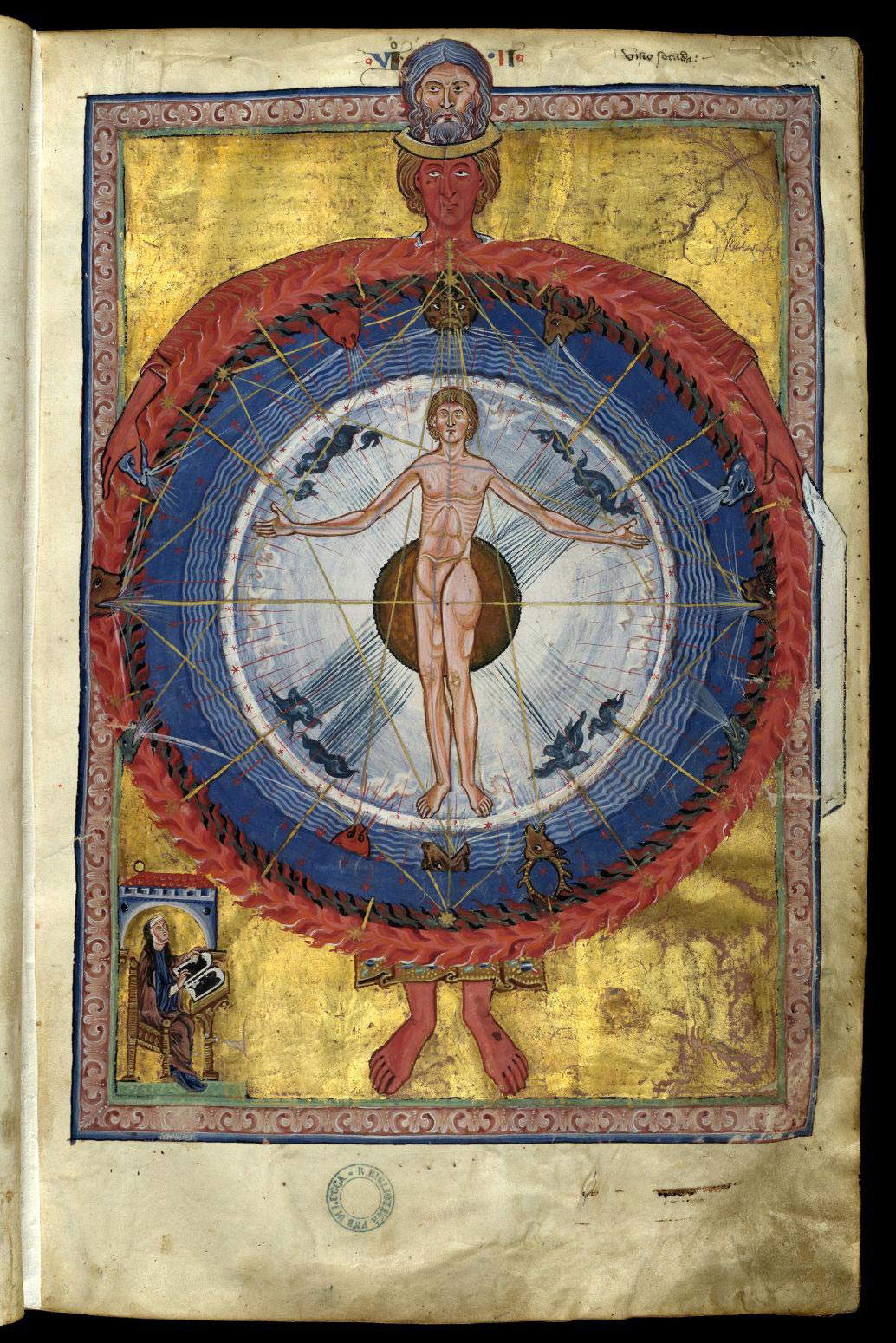

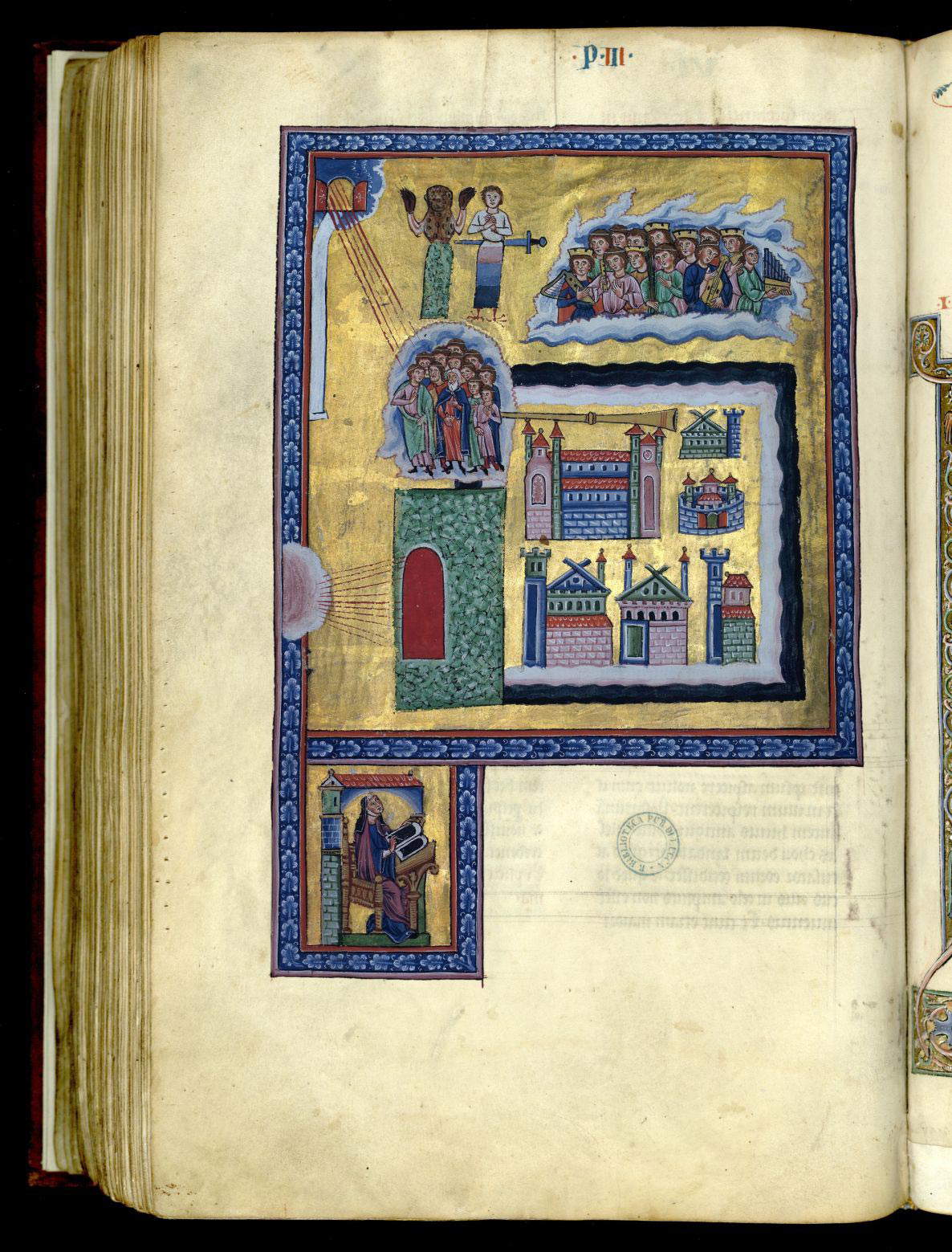

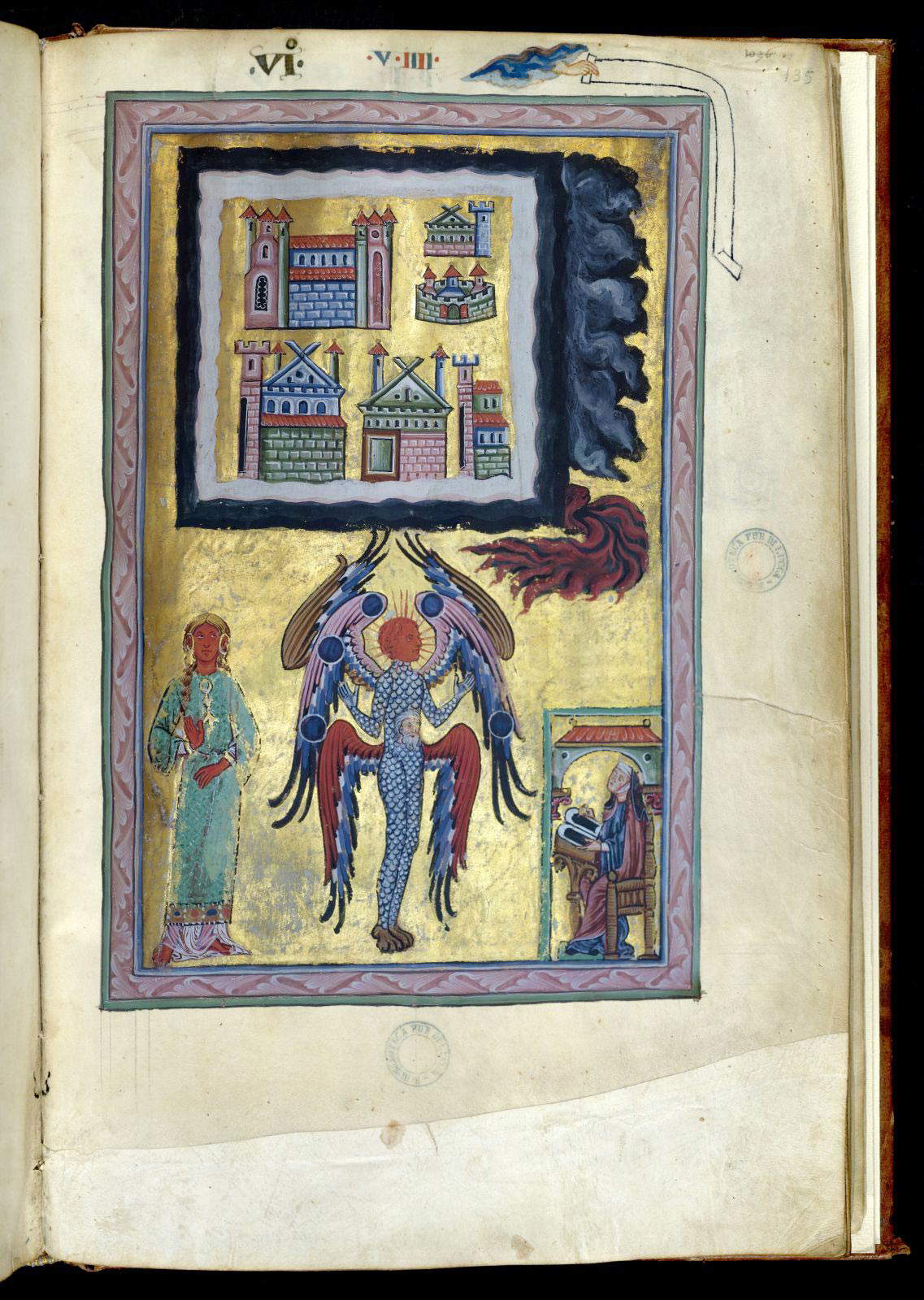

The work in the State Library of Lucca contains Hildegard’s visions in their entirety, and the text of each vision consists of a description in which the saint speaks in the first person expounding the content of the apparition. The first vision is that ofdivine Love, in which Hildegard summarizes the stages of the creation of the world and expresses from the beginning her idea about the universe, which before God was without form and was then ordered by his action, and was illuminated by his light: divine Love, in this vision, is the means for the salvation of humanity. In the second vision, to which is linked perhaps the best-known illustration in the Codex, Hildegard speaks of the human being as the central element of creation, though closely related to everything else in creation: the human being is, in essence, a microcosm located at the center of the heavenly spheres governed by God. In the third vision, the saint illustrates the ways in which the human being interacts with the cosmos (for example, how the cosmos acts on people’s moods and their bodies), while in the fourth, the relationship between the cosmos, body and soul is explored, with further references to the external influence that the macrocosm has on human beings (the saint also draws analogies between nature and the human body, for example, between rivers and veins). The fifth vision focuses on analyzing the globe, which Hildegard divides into five regions, with four corresponding to the four cardinal points and the fifth standing in the center and surrounded by the other four. The last four visions deal with the theme of salvation history. Of particular interest are the eighth vision, which delves into the three virtues (love, humility, and peace) by which God accomplished everything he created, while the ninth and tenth visions discuss the quality of faith and the end of time, cautioning about the fact that faith leads to salvation.

Each vision is followed, in the 1942 manuscript in the State Library of Lucca, by an explanatory commentary that is spoken directly by the voice of God appearing to the saint. The illuminated plates, as mentioned above, individually illustrate all the visions of Hildegard of Bingen; they are all full-page even though they are presented in different sizes and with a structure based on the combination of elementary geometric figures. Interestingly, in each of the miniatures there is, in the corner, a portrait of Hildegard, who is always caught seated, intent on her work, looking upward and always with the instruments of writing in her hands, or leaning but nevertheless just being used or about to be used: this figuration expresses the divine inspiration of her work. It should also be noted, as Anna Calderoni Massetti and Gigetta Dalli Regoli have observed, that the illustrations of the visions are not the perfect equivalent of what the text enunciates, but are to be considered rather as condensations of the individual episodes, those considered most relevant and intense, that Hildegard describes. Thus we see, among the various images, the Spirit of the world, the structure of the cosmos, the system of winds, the human figure placed at the center of the universe, the theme of the monster and fantastic and allegorical figures, the globe, and the scheme of the city of God.

It has been said that the depiction of man as a microcosm is probably the most famous in the manuscript, not least because it has been seen by many as a kind of precedent forLeonardo da Vinci’sVitruvian Man: In Hildegard, too, art historian Marco Bussagli has written, “we find astral correspondences between the man-microcosm and the universe contained by the figures of Christ and God the Father,” with Hildegard “marking stylized rays the influence of the sun on the head and the moon on the feet by referring to the late antique doctrine that theorized the influence of the planets on man.” Represented in the miniature are all the spheres of the universe, conceived as a set of concentric circles(circuli) that are moved by a circular motion in turn: the sky we all see, complete with clouds, and then the firmament (conceived as an aerial region consisting of dense white air surrounding the Earth), the fixed stars, the cosmic waters until we reach the circle of fire that surrounds the entire universe above which there is only God. The animals we notice along the spheres are personifications of the winds that move them: a bear (north wind), a lion (south), a wolf (west), and a leopard (east) represent the four main winds, while eight other animals symbolize the collateral winds (note, moreover, how in the miniature accompanying the fourth vision the winds appear together with the effects they produce on the earth). The full correspondence between humanity and the cosmos is also explained on the basis of the proportional relationship that exists between the two entities: according to Hildegard, for example, if a man stretches out his arms the width of his figure will coincide with its height, in the same way that the height of the firmament is equal to its width.

It should be considered that, although the complex of allegorical interpretations of what Hildegard says in the Liber divinorum operum is preponderant over the rest, the visions contain a rather precise physical description of the universe, which nonetheless responds to the desire to explain what happens under the heavens: for example, extreme weather conditions (intense heat, freezing cold) are explained on the basis of the existence of a “black fire” created by God to punish sinners, and which in turn is fed by winds blowing from the north and south producing opposite climates. When God’s fire is not in action, the “thin air” that surrounds the Earth produces beneficial effects for humans according to Hildegard: in particular, by turning into thin rain (in both heat and cold: according to the saint, snow itself is the result of freezing water droplets), it is able to make plants and fruits sprout.

Hildegard’s cosmology, Giulio Piacentini noted, draws its foundation from the Liber Nemroth, a Jewish book with which she shares the idea of a revolution of the planets and firmament according to the action of the winds: the saint therefore “departs, at least in part, from the theories of traditional Aristotelian-Ptolemaic cosmology,” the scholar explains, “which considers the cosmos as a reality consisting, among other things, of a series of concentric crystalline spheres to which are set the planets revolving around the Earth, placed at the center of the universe.” What separates Hildegard from the Aristotelian tradition is the absence, in the Liber divinorum operum, of references to the motive intelligences of the spheres, which Hildegard evidently replaces with the winds, thus intending to explain one aspect of reality not with elements of a metaphysical order, such as the driving intelligences, but with a physical element, namely the wind (although to explain reality as a whole, Hildegard asserts, it is still necessary to assume a primary cause of a metaphysical order). Ultimately, it can be said, as Calderoni Massetti and Dalli Regoli have pointed out, that the Hildegardian vision is similar to that of a machine, “where carefully devised mechanics produce slow and continuous movements, dislocations , improvised appearances and escapes; where an imaginary lighting apparatus provides for both gradual transitions from darkness to penumbra to full light, and attimal leafing.”

The illustrations in the 1942 manuscript in the Lucca Library provide an important, immediate and easily understood iconographic accompaniment to the concepts Hildegard expresses in her visions. Consequently, the Lucca codex has long been studied, and there is a vast bibliography devoted to the Liber divinorum operum, partly because of the interest that the figure of Hildegard has aroused, especially since the second half of the 20th century. In particular, numerous studies have been published on the figure and work of Hildegard of Bingen, also in relation to the art-historical aspects of the illuminated manuscripts illustrating her works. Which have never overlooked the extreme importance of the manuscript preserved at the State Library of Lucca, the oldest witness, and the only illustrated one, of the Liber divinorum operum.

The State Library of Lucca

The State Library of Lucca originates from the Library of the Lateran Canons of San Frediano, established in the 17th century by Abbot Girolamo Minutoli, and later undemanized by the Republic of Lucca in the second half of the 18th century. In 1791 it obtained from the Republic the right to print for Lucca and annual funding for the purchase of books. Instead, it was opened to the public in 1794. In 1861 the Library passed to the Kingdom of Italy, and a few years later, in 1877 it was moved to its current location, the convent of the church of Santa Maria Corteorlandini, shared with the Order of the Clerics Regular of the Mother of God. The move became necessary as a result of the conspicuous allocation of the funds of Lucca’s ecclesiastical libraries after the suppression of the monastic orders: among the collections that flowed into the State Library was also the original “Library” of the Order of the Clerics Regular, consisting of some 13,000 volumes, and collected in the seventeenth-century Hall known as the Hall of Santa Maria Nera, located on the top floor of the building. Today the Library depends on the Ministry of Heritage and Culture.

The Library’s collections include 451,300 printed works including volumes and pamphlets, 4,321 manuscripts (volumes), 19,478 (loose), 835 incunabula, about 10,000 cinquecentine, 2,650 periodicals of which 594 are current; 627 Lucchese newspapers. Particularly valuable among the many manuscript collections are the Baroni Fund, which contains genealogical news and coats of arms of Lucca families; the Fiorentini Fund, which concerns the Lucca physician and botanist of the same name; and the Cesare Lucchesini Fund. The State Library of Lucca preserves many illuminated manuscripts including the 37 choir books, the Liber Divinorum Operum of St. Hildegard of Bingen, and the 15th-century Missale Romanum, which belonged to Bishop Stefano Trenta of Lucca. Of notable importance are the legal fund of the works, writings, legal memoirs, documents and letters of the Lucchese penalist Francesco Carrara, that of popular literature by Giovanni Giannini, and that of the Lucchese painters and art writers Michele and Enrico Ridolfi. Notable among the correspondence is the collection of letters to Paolo Guinigi, de facto lord of Lucca in the early fifteenth century (the letters date from 1400 to 1430), the 13 volumes of letters addressed to Cesare Lucchesini, the 9 volumes of letters addressed to the poetess Teresa Bandettini, the letters, six hundred, of Giovanni Pascoli, and the vast correspondence of Michele and Enrico Ridolfi.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.