Landscape painting represents one of the most heartfelt subjects of the Macchiaiolo movement, which has left us pieces of great intensity on the genre that can testify to that new approach that the Tuscan group, proponents of a reborn realism, was able to instill in the art of its century. “You will have no other school than truth and nature,” admonished his pupils Giovanni Fattori, who managed to be one of the most important protagonists of that movement. After all, it was precisely the group of artists who referred to the Caffè Michelangiolo in Florence who had proposed in the landscape, and in particular the sparsely man-made natural landscape, their own anthem, capable of imposing itself as an autonomous subject, without making it subordinate to narratives or relegated to the background of anecdotal scenes.

It is no coincidence that, although these painters got their start in the Tuscan capital, the only city in the region capable, at that time, of guaranteeing a certain cultural effervescence, they elected as their places of retreat and productivity rural or uncorrupted destinations, where the encounter with nature suffered less interference. On the silence of the Sienese hills began to form that handful of artists who were already on the move before the “macchia” proper and who gathered around the Hungarian painter Andrea Markò, and in which the Leghorn-born Serafino De Tivoli, who of the Macchiaioli was one of the most preponderant personalities, especially at first, also participated. In the school of Castiglioncello, a town not far from Leghorn, a part of these artists gathered instead, who in the communion of sun, sea, cliffs and greenery found an inexhaustible sampler, while to this they preferred more the quiet passing of domestic life in the Florentine countryside the artists of the Piagentina school.

But in the canvases and plates almost always with longitudinal development also ended up being eternalized countless other views of Tuscany in which, with the exception of the city of Florence and little else, it was above all the rural theme that dominated, as much in the views of the Maremma as in those of Elba or the Livorno coast of Antignano. Among the locations in the endless Macchiaioli mapping are also areas in the province of Pisa, although undoubtedly fewer studies have dwelt on investigating this aspect. Not dissimilar to the aptitude shown for other localities, attention to the Pisan lands was mainly focused on those authentic and spontaneous landscapes still scarcely urbanized that the vast province offered. In particular, a vast production found interest in those silent territories, where the green of the trees thins out to let the Arno River flow placidly.

Among the area’s fondest patrons was Giovanni Costa, known as Nino, a Roman painter who had the merit of making Giovanni Fattori abandon the academic approach in painting in favor of a freer naturalism. The Roman painter was so enchanted by Bocca d’Arno, the name by which the mouth of the Tuscan river is identified, that he elected the locality his home from the early years of the second half of the nineteenth century, and catalyzed prominent figures in the Italian and Anglo-Saxon artistic and literary worlds with his presence. From his memoirs we get a sharp picture of the affection he had for these places: “The coast of the Pisan Sea was the country place where I dwelt the longest and where in greater numbers I found subjects for my painting. The light, the marshes, the magnificent trees with the background of the sea and the grand Apuan Alps and Monti Pisani, make this one of the most beautiful and picturesque sites in the world. [...] At Bocca d’Arno even before a single house was built I went to live and paint there.” Evocative is the work Il Fortino di Bocca d’Arno painted around 1885, a subject among his most beloved and which he had already known in the years of his youth spent in Tuscany and painted in 1855.

Still of great intensity is the work The Dead River at the Combo in Pisa. Landscape with River, where he depicts the Dead River, a waterway a few kilometers from the mouth of the Serchio, which channels the waters of a vast area between the Arno, the Serchio and Mount Pisano, but which, because of its low gradient, tended in the past to swamp among the reeds and woods. “I painted the sketch of my great picture Fiume Morto, in which I figure a section of this great ditch that [...] flows among the pines and oaks so slowly that it seems, its, dead water. Among the trees forms the background of this picture, purplish the Pisan mountain.” Also known of this work is a small tablet, a very fresh study made en plein air, not at all far from the temperaments of the Barbizon school, which was chosen by the author for the Wolverhampton International Exhibition of 1902. In the reworking on the large format, Costa renders the scene more terse and less brilliant, a scene in which an almost melancholy atmosphere hovers. It is a painting that abounds in transparencies and chromatic sensitivity, and with exquisitely romantic flair registers variations in atmosphere and light.

Not far away is Gombo, a resort also on the coast of San Rossore, among the first to have had a seaside development, and later privatized by the House of Savoy, which wanted to make it its own by building an elegant chalet there. Il Gombo became the subject of a crystalline view by another of the artists who, albeit in a different geographical area of Italy, Liguria, contributed to the anti-academic and naturalist renewal, Ernesto Rayper, progenitor of what is known as the “gray school” or “of the grays.” Rayper painted the Gombo beach in 1864, with the sedge huts used by fishermen and bathers, when the beach had still been granted to the Ceccherini family for public bathing and had not yet been interdicted by the ruling house.

Less limpid is the view with the pilings of the Gombo bathing establishment rendered in Emilio Donnini’s painting, poised between a romantic landscape setting and a more realistic transcription, typical of those artists who were close to the Markò family. The following year the painter exhibited it at the 1865 Exhibition of the Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts, where it was purchased for 300 liras by the ill-fated Prince Oddone of Savoy.

The stretch of the Arno River flowing through the San Rossore estate was also painted by Serafino De Tivoli, a painter for whom the term “babbo della macchia” was coined, who was on good terms with Nino Costa. In 1857 he exhibited in Florence five paintings set along the banks of the Arno in Pisa. Of these, The Arno at San Rossore would seem to be a straightforward composition of the landscape, purged of those lyrical accents instead dear to Costa and showing a luminous palette played on greens, blues and whites and a textured brushstroke.

Still different is the reading Giovanni Fattori offers in his panel known as Laghetto a San Rossore or San Rossore - Reflections. The view narrows in on a portion of the body of water and the few branches of the trees that overshadow it, while behind it opens up a clearing whose depth is hinted at only through the modulation of color and luministic gradants, offering a most vivid impression of the landscape. The Leghorn master in the Pisan countryside would set other great masterpieces such as Cavalli bradi nella pineta di Tombolo and Tombolo.

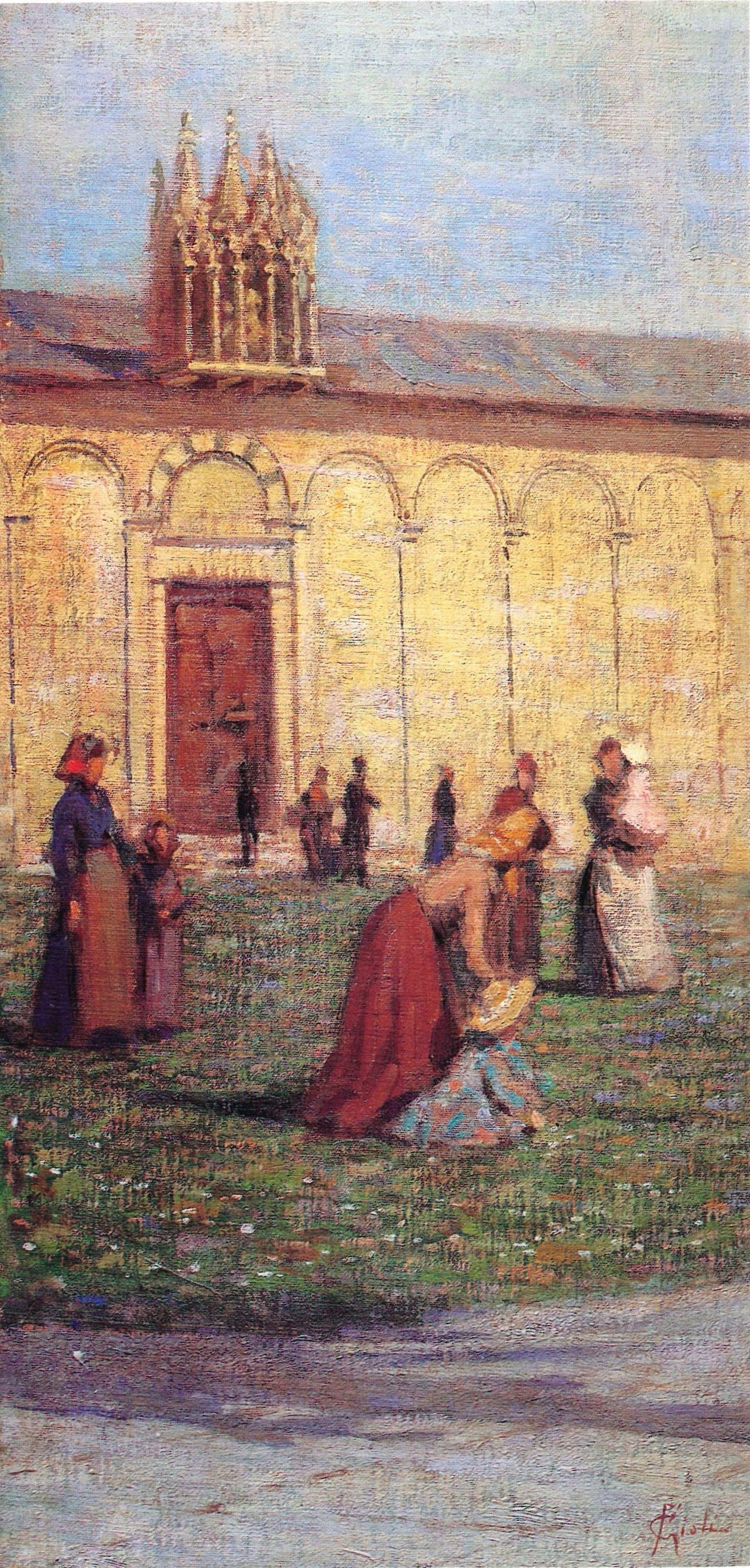

Rather, another of the fathers of the Macchiaiolo movement, Silvestro Lega, preferred the rustic hinterland to the river and coastal wilderness.A number of his works are known to have as their subject the placid and rustic life of the village of Crespina, where the Modigliana painter resided in 1886, hosted by Angiolo Tommasi, whose family had a villa there. During his stay he produced a number of works such as La Chiesa di Crespina, a painting that already shows that excited manner that critic Mario Tinti identified as the artist’s last period. The scene, set on a certain formal essentiality and constructed through lean colors impastoed and conceived with great synthesis, brings out from time to time the support of the canvas, of which the color is functional for the rendering.

Less rich is the production of works whose protagonist is the historical center of the city of Pisa, which, on the other hand, had a completely different iconographic fortune in the painters of other epochs, both of the past and of the generations immediately following the Macchiaioli. It is, however, a frequent aptitude in the geography of the Tuscan compage, which was generally uninterested in city planning, except for glimpses of Florence and little else.

Some interest, however, was catalyzed by the architecture of the Gothic Camposanto in Piazza dei Miracoli, whose mass pierced by windows with mullioned windows is the subject of a careful painting by Giuseppe Abbati, who on July 4, 1864, was a guest of Diego Martelli, who had several properties in Pisa. Odoardo Borrani and Vincenzo Cabianca also dealt with the same theme.

Decidedly more generous and abundant in references to the architecture, churches and streets of the city of Pisa is the work of the Gioli brothers, Francesco and Luigi. Both born in a hamlet of Casciana, a town in the Pisan countryside, the two painters continually stopped their attention as much on the rural theme as on city views.

Francesco, whose beginnings lay in close contact with the Macchiaioli current, would later, as did his brother, experiment with models, which in intent and rendering departed from the Tuscan tradition, welcoming innovations from beyond the Alps. The two brothers would thus become a reference for that generation of artists known as the “postmacchiaioli,” painters for whom the interest in landscape did not wane, but with different intentions and attentions.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.