An article written by an anonymous journalist and published on December 22, 1928, in The Literary Digest, a popular U.S. weekly newspaper at the time, recalled a singular story that had occurred five years earlier. A wealthy American collector, thirty-five-year-old Helen Clay Frick (Pittsburgh, 1888 - 1984), daughter of steel magnate Henry Clay Frick (West Overton, 1849 - New York, 1919), the founder of the Frick Collection, purchased from Italian antiquarian Elia Volpi (Città di Castello, 1858 - Florence, 1938) a spectacular marble sculptural group depicting anAnnunciation and consisting of an Announcing Angel and an Announcing Virgin. The two sculptures were attributed to one of the greatest medieval artists, Simone Martini (Siena, 1284 - Avignon, 1344), and the attribution seemed corroborated by the initials “S.M.” appearing on the base of the angel and the date “1316” inscribed on that of the Madonna. Vouching for the goodness of the attribution was collector and art historian Frederick Mason Perkins, with whom Helen Frick, in the company of Volpi himself and his friend Gertrude Hill, had viewed the two statues at a villa just outside Florence.

The two statues were reminiscent in every way of Simone Martini’s celebrated Annunciation preserved in the Uffizi: yet, despite the reliability of Perkins and Volpi himself, then one of the most prominent antiquarians on the market, able to deal with works by great artists of the past in order to sell them to an international, prestigious and select clientele, there was no trace of Simone Martini’s sculptural activity, which is why the collector wished to receive the opinion of other experts. Two scholars, such as Charles Loeser and Giacomo De Nicola, expressed themselves in favor of assigning Simone Martini, and as a result Helen Frick decided to complete the negotiation. The young woman paid the agreed upon $150,000 (a very high figure: it corresponds to about $2 million today) and the two sculptures, in March 1924, landed in New York. At this point the problems began for Helen Frick, because many scholars and enthusiasts overseas began to have doubts about the two sculptures, so much so that additional opinions were needed, such as that of Wilhelm von Bode who, while noting the absence of information about any sculpture by Simone Martini, noted that “the anatomy, the folds, the expression everything is Simone’s art” (these were Bode’s words that Elia Volpi quoted in a letter). Volpi and Perkins branded the suspicions as hearsay, but this was not enough to convince the collector who, in 1925, had the statues examined by a commission of experts, who in the fall of that year gave their response: the works were two forgeries. Against a fourteenth-century authorship lay, according to the scholars who had analyzed the group, the position of the heads, the relationship between one figure and the other, the lack of credibility of the way the date had been affixed, and the “general effect” elicited by the two statues. Frick therefore asked Volpi for the return of his money, but the merchant, declaring himself in financial difficulty, proposed a drawing by Leonardo da Vinci as compensation.

It had meanwhile come to 1928, and finally, with the deflagration in November of that year of an international scandal, it had come to light who was the real author of the two statues: it was the Lombard forger Alceo Dossena (Cremona, 1878 - Rome, 1937), who that very year found himself at the center of a worldwide case, since the numerous statues that, passed off as originals from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, had been shipped in great abundance to the United States, with the involvement of numerous scholars of the highest order, had come to light. Helen Frick’s fake Annunciation thus remained very little in her home: as early as February 1933 the two statues were given to the University of Pittsburgh, which still owns them.

|

| Alceo Dossena, Announcing Angel (1920-1923; marble, 213 x 228.5 cm; Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Art Gallery) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Virgin Announced (1920-1923; marble, 213 x 252 cm; Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Art Gallery) |

|

| Dossena’s two statues in their placement in Pittsburgh |

The Dossena case had erupted at a time of great activity in the antiquities trade between Italy and the United States, and it was precisely this scandal that was one of the causes that brought about the end of a flourishing market that had begun as early as the 1870s and that had brought across the Atlantic numerous ancient works from Italy but also, as would be discovered in that turn of years, numerous forgeries. The intensification of international travel and the love for Italy on the part of wealthy travelers, especially English and Americans, had given rise to a great love for the art of our country, especially Gothic and early Renaissance art, with the result that, by the end of the nineteenth century, especially the cities of central Italy (especially Florence, which became the main center of this market) became populated with merchants and brokers, sometimes serious and reliable but very often improvised, who sold all kinds of antique goods to their clientele, so much so that, in 1902, the first law on the protection of cultural property in the history of Italy became necessary. Such a thriving market, so conditioned by expertise, could not remain immaculate for long, however, and soon a number of forgeries began to operate in the marketplace, many of them, such as Federico Joni, Giovanni Bastianini, Umberto Giunti, Gildo Pedrazzoni and Dossena himself, of great talent and skill. Joni, who specialized in painting, had such extraordinary skills that he seriously disturbed the market for Sienese and Florentine gold funds: he was also a most singular character, who went so far as to write an autobiography, the Memoirs of a Painter of Old Paintings, published in Italy in 1932 and in England in 1936. And it was the success of this literary work of his that contributed to the climate of suspicion that had already clouded the Italian market. Joni had shown himself capable of imitating the style of many Old Masters with exceptional skill, counterfeiting the panels with a patina that gave a very realistic antique look to the works, and in addition he had also made proselytes (the aforementioned Umberto Giunti, who specialized in fake fragments of frescoes and paintings in the style of Botticelli, was one of his pupils).

Dossena, on the other hand, was the greatest among sculpture forgers. And to the other greats like Joni and Giunti he shared a definite characteristic: these formidable falsarî did not simply reproduce ancient paintings or sculptures. No: they were endowed with an astonishing inventiveness, they had their own personality that led them to create works of art rather than imitate them. “I invented in the manner of the great masters, but I always invented,” said Alceo Dossena to claim the autonomy and prestige of his own art.

The forger whose works were able to deceive legions of connoisseurs came from a family of humble origins: his father worked as a porter for the railways at Cremona station, his mother was a seamstress, and little Alceo was accustomed to work from an early age, since his family was poor. From childhood, however, he had developed a passion for art: the biography written by his son reports that he soon learned to paint and sculpt as a self-taught artist, honing his knowledge with frequent visits to the Cathedral and churches of his hometown, but from other sources we know that at the age of twelve he entered the “Ala Ponzone” art school, only to be expelled the following year: his father tried to readmit him but to no avail. So Alceo began working as a stonemason in the workshop of a local stonemason, and then began a period of apprenticeship in Milan, in the workshop of Alessandro Monti. The first forgery of an ancient work seems to date back to 1916: a Madonna and Child, which the forger “aged” by placing it in a urinal (one of Dossena’s most admired talents would have been precisely his ability to lend a credible antique patina to his sculptures). Dossena, who was serving in the army at the time, tried to sell the work to a bartender-the intent was to scrape together some money to make Christmas presents for his family. The bartender did not show interest, but the work attracted the attention of a wealthy jeweler, Alberto Fasoli, who was in the tavern and thought Dossena had stolen the statue from a church. He therefore bought the statue for one hundred liras. Fasoli, after some time, realized that the statue was not ancient: yet, he was not angry at the forger, but had the idea of putting him at his service. He arranged with an equally shrewd colleague, Alfredo Pallesi, set up a studio for Dossena, guaranteed him a monthly salary, and began to market his works by passing them off as ancient.

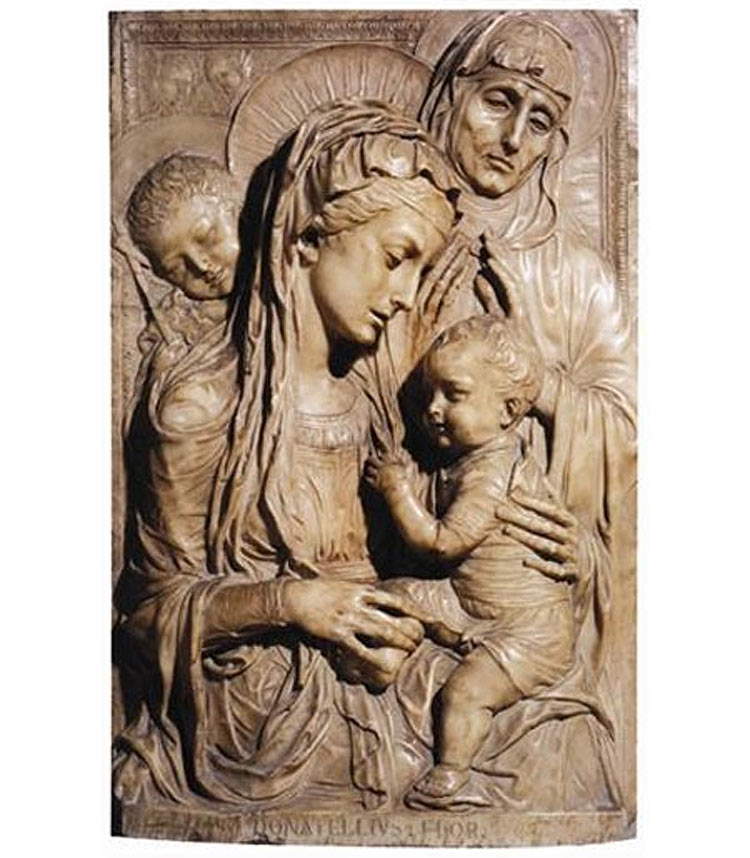

It is highly probable that Alceo Dossena himself had been duped by Fasoli, who sold his works at a high price, paying him a salary that, in relation to the figures the dishonest antiquarian earned from the sales, was decidedly meager: according to Dossena’s later statements, Fasoli allegedly told him that a Renaissance-style church was being built in America, which needed to be appropriately decorated with sculptures similar to those made in the fifteenth century. The sculptor, meanwhile, had specialized in imitating the style of a large number of medieval and Renaissance sculptors: Giovanni Pisano, Nino Pisano, Donatello, Francesco di Giorgio Martini, Mino da Fiesole, and others. When needed, he was also able to create mock Etruscan and Greek sculptures. Fasoli and Pallesi, meanwhile, had begun to defraud collectors but also museums: one of the most notorious scams was the one foisted by Volpi (who had bought the work from Fasoli and Pallesi) on the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which purchased a funerary monument of a fifteenth-century noblewoman, Maria Caterina Savelli, passed off as an original by Mino da Fiesole (an absurd scam when you consider that the monument bears a date “1430,” but the sculptor was born in 1429!). And the same museum also purchased, moreover, again from Volpi, a Madonna and Child in polychrome wood attributed to Vecchietta. All at considerable sums: the fake monument had cost $100,135, the Madonna $30,750. Even for buyers, Fasoli and Pallesi invented stories that sounded convincing to many: for example, that the sudden appearance on the market of so many works was due to the discovery of the works from an abbey that was located in ancient times on Mount Amiata (which never actually existed) and which, according to the story, had been destroyed by an earthquake. Meanwhile, the two were also doing business with other antiquarians, since, as mentioned earlier, some of Dossena’s works were sold to Volpi by Fasoli and Pallesi themselves. And they succeeded in deceiving scholars: the story goes that a young John Pope Hennessy, upon seeing a Madonna and Child, St. Anne, St. John and two cherubs by Alceo Dossena (now in a private collection), passed off as a Donatello (it was purchased by the English antiquarian George Durlacher in Venice for the exorbitant sum of three million lire), wept moved by the importance of what was thought to be an exceptional find.

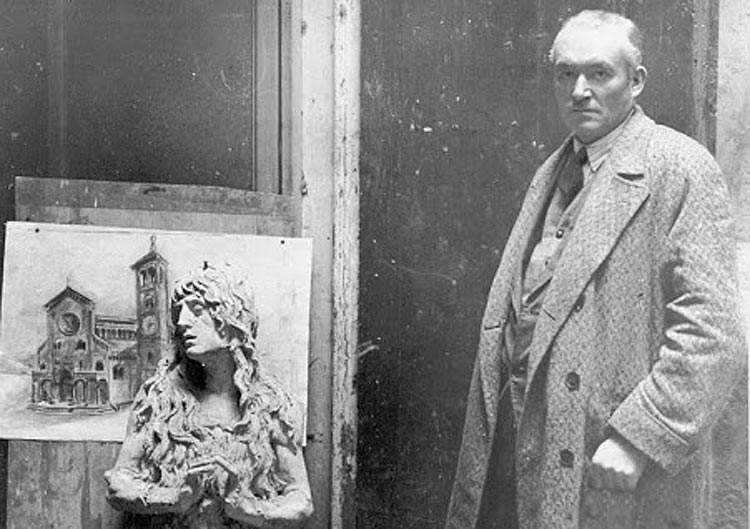

|

| Alceo Dossena |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Tomb of Maria Caterina Savelli (ca. 1920; marble, height 180 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child (ca. 1920; marble, height 134 cm; Boston, Museum of Fine Arts) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child, St. Anne, St. John and Two Cherubs (1926-1927; marble, 105 x 67 x 15 cm; Milan, Private Collection) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child (1929; marble, 81.3 x 81.9 cm; Detroit, Detroit Institute of Arts) |

This market could flourish thanks to the eagerness for Italian antiquities that gripped American collectors and museums, and on which Fasoli and Pallesi could march for years. But it was not long before some buyers realized that they had been cheated, and to the two dishonest antiquaries came the first demands for restitution. Thus two events happened that we can consider the antecedents of the scandal. The first was the lawsuit brought by Fasoli against Dossena: since the sculptor, if things had taken a turn for the worse for the swindlers, was liable to become an extremely inconvenient person, since, as far as we know, he was probably unaware of his antiquarian’s plots (and moreover, he was receiving low fees in relation to what Fasoli and Pallesi were earning from the scam sales, and the two did not even cover his out-of-pocket expenses and materials), the jeweler thought of striking him down by denouncing him for anti-fascism, on the charge of uttering insulting phrases against Mussolini while he was making a bust of him. The second was the arrival in Italy of an art historian, Harold Woodbury Parsons, who at the time was working for the Cleveland Museum of Art (one of the institutions defrauded), and who set out on Dossena’s trail and found him, eventually getting him to reveal that it was indeed he, Alceo Dossena himself, who was the author of those works believed to be ancient.

Dossena managed to get out of the trial unscathed: he was acquitted for lack of evidence, thanks in part to the intercession of one of the most powerful Fascist hierarchs, Roberto Farinacci, the ras of Cremona who, between 1925 and 1926, also held the post of secretary of the PNF. In turn, Dossena sued Fasoli for fraud, embezzlement and slander, but the trial had the same outcome, and in December 1930 the antiquarian was in turn acquitted for lack of evidence. The press and public opinion, meanwhile, had sided with Dossena, who was also believed to be a victim of the two shady dealers’ deception. And the consequence was increased interest in his work: coming out of the closet at last, he could proudly claim his talent, signing works and receiving important commissions, and working both for public commissions and to satisfy private collectors. Among the latter, the most loyal was probably the lawyer Alessandro Ansaldi, who was perhaps joined by the latter’s son, Carlo Francesco, also a lawyer: the two gathered an important collection of Dossena’s works, which has now become public. In 1981, in fact, Alessandro’s nephew, art historian Giulio Romano Ansaldi, donated the collection to the state, which was first transferred on deposit to the National Gallery in Rome and has now been in permanent storage at the Museo Civico di Pescia (Pistoia) since 1989.

The works in the Ansaldi collection show, scholars Federica Gastaldello and Emanuele Pellegrini have written, that Dossena was “an artist capable of a high-profile production not necessarily anchored in the activity of forgery, supported by a linguistic variety and a divulgative intent still to be studied with due attention.” Ansaldi’s works include a Magdalene published for the first time on the occasion of the exhibition Voglia d’Italia, held at the Vittoriano and Palazzo Venezia between December 2017 and March 2018: the Magdalene, very close to Donatello’s counterpart, denotes a “sure sign [...] that not only looks to Donatello, but also violates and rereads in negative linquieta elegance of some Bistolfiana or Ieraciana female figures,” and a “conscious use of a fifteenth-century source loaded to the maximum of its expressiveness” that “becomes a picklock to approach the sculpture of his time” (so Gastaldello and Pellegrini).

|

| Alceo Dossena, Penitent Magdalene (1920-1930; terracotta, 55 x 45 x 17 cm; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Saint Francis (1932; bronze; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child with Angels (1925-1937; terracotta; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child (1930-1937; terracotta; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Madonna and Child (1930; bronze; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Portrait of Giuseppe Verdi (1900-1924; bronze; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

|

| Alceo Dossena, Dog (1930; terracotta; Pescia, Museo Civico Galeotti) |

But how was Dossena able to create such lifelike works? The artist had developed a special technique for imitating the natural aging of sculptures: “his patina,” wrote scholar Giuseppe Cellini in the entry dedicated to Dossena in the Dizionario biografico degli italiani, “is not a superimposition of materials, such as that found in excavated sculptures, but is an underlying shade of color to the epidermis, penetrated inside by degrees, fixed indelibly in the undercuts, as precisely occurs in medieval and Renaissance marble. This is not a matter of an imbrication given and retinted at the finished work, according to the method used by other forgers: his ingenious procedure was to sculpt the compositions almost to completion, with planes smoothed by the step, and at that point apply a liquid patina made of permanganate, rust water and oak earth dried in the heat of the gas flame. This masked the entire surface with a blackish crust; then, on finishing, with flat chisels and chisels he would cleanse the surface itself and, as to a fruit, uncover the pulp of the marble, with the inner halo of patina, as in the ancient. When the parts in question were then polymerized with lead and oxalic acid, and the fractures and accìdental damage were added, the maquillage was perfect.”

Many museums disposed of his works, but there are many others where they are still preserved instead, and often all but hidden. Dossena’s story is also an extremely significant moment in art history, embedded in the period when the market for antiquities developed, conservation laws were born, museums were beginning to expand and meet public interest, and the great collectors of the early twentieth century were forming astounding collections. Today, with the progress that studies have made and with the expansion of the scientific community, works like Dossena’s could hardly fool scholars, although the problem of forgeries is far from being eradicated. In any case, Alceo Dossena also became for his hometown a sort of boast, so much so that, in 2003, the association of the Friends of the “Ala Ponzone” Museum in Cremona wanted to donate to the institution a work by Dossena, a terracotta tondo depicting a Madonna and Child. It was only right, according to the supporters of the initiative, that at least one of his works be included in the itinerary of the Cremona civic museum, to remember the greatest forger that Italy has known, a unique and unrepeatable witness of a cultural temperament and an important piece of art history and of Italy.

The author of this article: Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta

Gli articoli firmati Finestre sull'Arte sono scritti a quattro mani da Federico Giannini e Ilaria Baratta. Insieme abbiamo fondato Finestre sull'Arte nel 2009. Clicca qui per scoprire chi siamoWarning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.