The Imbriani Fund, between Neapolitan folk song and correspondence of the great man of letters

Vittorio Imbriani (Naples, 1840 - 1886) was one of the most important exponents of 19th-century Neapolitan culture. Born to Paolo Emilio Imbriani and Carlotta Poerio, the latter sister of the Risorgimento poet Alessandro, he lived his youth between Nice, Turin and Zurich (in fact, he followed the movements of his father, who was forced into exile because of his political thoughts), studying Italian literature (and Petrarch in particular) in Switzerland with Francesco De Sanctis, and then moved in 1860 to Berlin where he had the opportunity to study Hegel’s thought. Returning to Naples in 1861, he began teaching aesthetics in his hometown and shortly after, in 1866, enlisted and participated in the Third War of Independence: he was captured during the Battle of Bezzecca and sent as a prisoner of war to Croatia. He managed to return a few months later to Naples where, in 1872, he would found the Giornale napoletano di filosofia e lettere: after marrying Luigia Rosnati in Milan in 1878, he began to develop signs of a spinal cord disease that would lead first to paralysis and then to his demise. Imbriani’s most important legacy is preserved at the University Library of Naples, where the Imbriani Legato is housed, gathering 5,018 works, 1,190 pamphlets and 583 loose papers: within the collection are works written but also consulted by Imbriani. The latter also include rare editions, cinquecentine, tourist guides, series of classics, atlases, texts on medicine, science, art and archaeology, as well as, of course, literature (the collection also counts several editions of the Divine Comedy).

The bequest came to the Library of the Royal University, as the University Library was then called, on November 20, 1891 by decision of the widow Luigia Rosnati, who in all likelihood went along with her husband’s wishes and made a proposal to the institution to acquire Vittorio Imbriani’s library en bloc: by doing so was avoided, wrote the scholar Vincenzo Trombetta, the dispersion “of a resource of substantial economic value that - sold to ravenous booksellers or wealthy collectors - also would have contributed to feed the certainly not florid economic state of the family.” Few conditions were set by Luigia Rosnati: the bookstore was to be housed in a reserved room named after her husband, and to see the presence of a bust of him, which was made in bronze by one of the greatest artists of the time, Achille d’Orsi (Naples, 1845 - 1929), among the main protagonists of verist sculpture (today the bust can be admired in the Monumental Hall of the Library). And again, we read in the deed of gift that “The books...shall not for any reason split up and merge with the others of the Library, but in any event even of change of location, shall constitute a separate fund with the title: Imbriani Fund.”

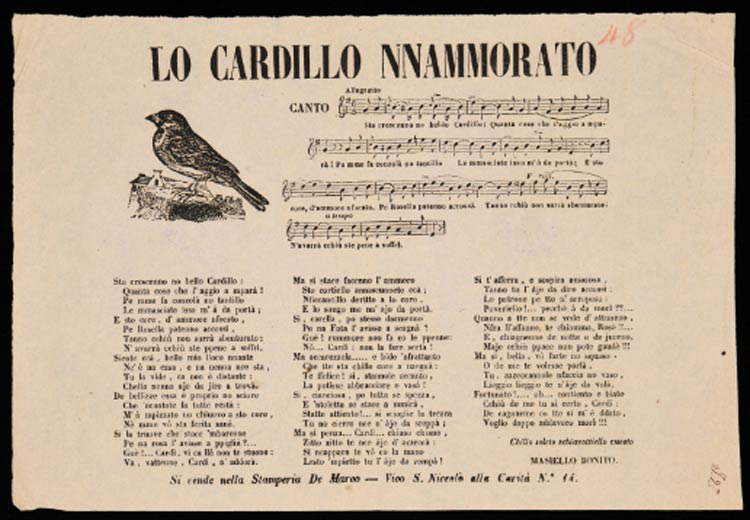

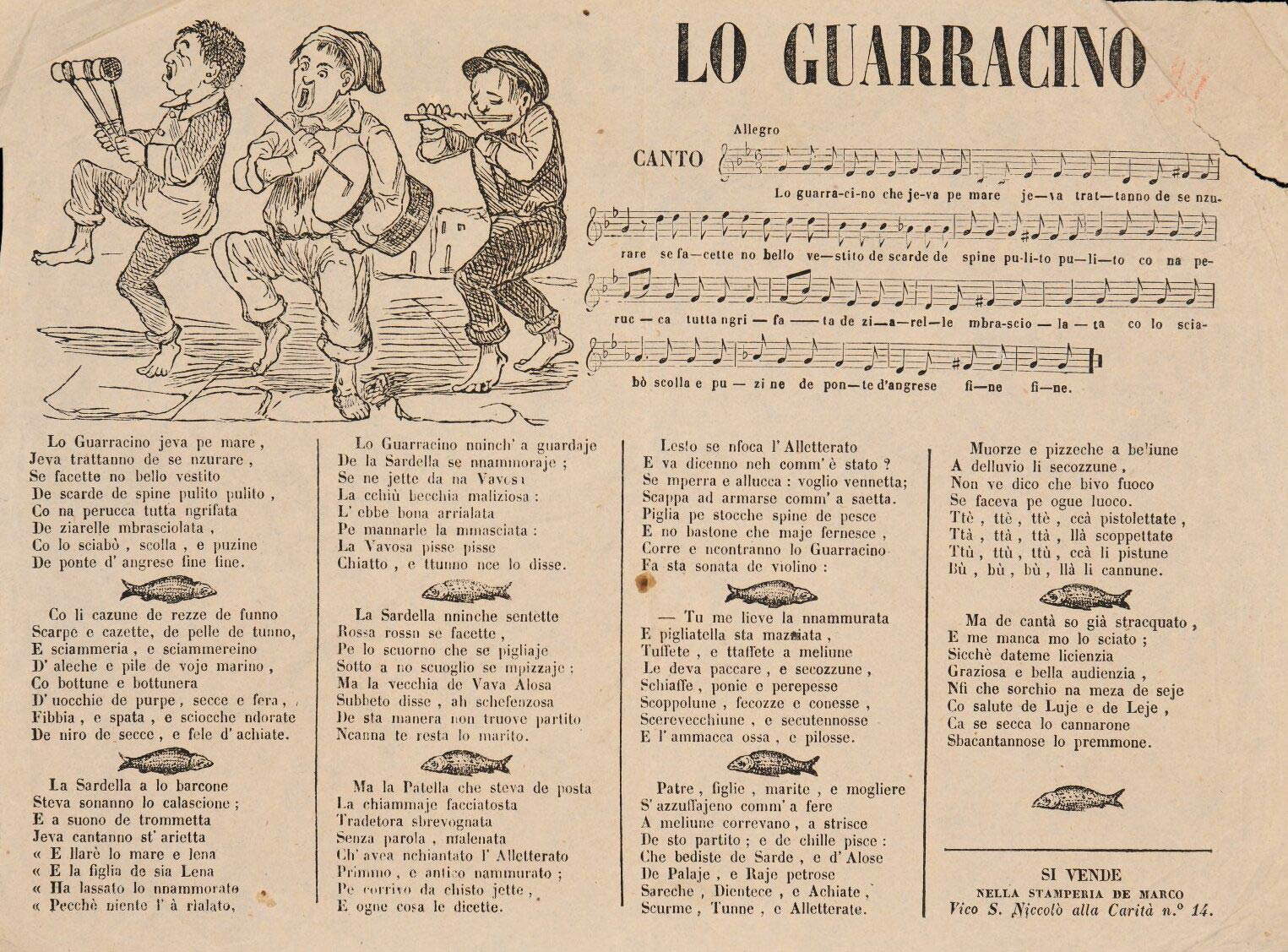

Perhaps the most valuable part of the Imbriani Legate is that which concerns popular literature, of which the writer and patriot was a great scholar: in fact, his works include collections of fairy tales and novellas that the Neapolitan tradition handed down orally, such as La novellaja fiorentina published in Naples in 1871, the Canti popolari delle provincie meridionali published by Loescher between 1871 and 1872 and the XII conti pomiglianesi, published in Naples in 1877. Also worth mentioning are the sheets with Neapolitan folk songs that were printed in the city on the gulf between the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: these are traditional songs (e.g., ballads, tarantellas, villanelles, farces, frottole), often adapted and transcribed on scores, complete with illustrations. This is, for example, the case with Lo cardillo ’nnammorato, or Don Ciccillo co’ lo parapalle by Antonio Tasso, whose title refers to the hat worn by Neapolitan liberals as a symbol of protest against the Bourbon government, or again with Lo guarracino published in an unspecified year of the 19th century by the Stamperia De Marco: the latter is one of the best-known Neapolitan tarantellas, of eighteenth-century origin, and is about a fish, the “guarracino” precisely, or black castagnola, which provides an opportunity to list a series of fish and mollusks that sing and dance in the waters of the Gulf of Naples.

As a result, Imbriani was in possession of numerous texts of popular literature, a collection consisting of 600 documents that, explains the University Library of Naples, “represent extraordinary printed records of the culture of the humble classes, often handed down only by oral tradition. Vittorio Imbriani should be credited with the great merit of having restored dignity to this type of ’minor&rquo; literature, which analyzes a world on the margins of society and which has now disappeared: the thousands of trades practiced in Naples rise to art-not only that of getting by to make ends meet, with honesty and with dignity-but also to authentic identity culture.”

Popular literature circulated on texts that came out of the print shops in the historic center (located mostly between Via San Biagio dei Librai, Via San Gregorio Armeno, Via dei Girolamini and the immediate vicinity), which had experienced a wide circulation thanks in part to the accessibility of these products: they were in fact printed on poor-quality paper, the booklets were often untrimmed, and the proofs were proofread to the best of their ability, and the illustrations themselves were modest and made by artisans with some artistic ambitions. Pamphlets and booklets were sold cheaply on the streets and in the hallways of palaces. In any case, these are works documenting a popular culture whose origins are lost in the mists of time, and much of which probably would not have survived without this conspicuous production. Imbriani collected part of his booklets with songs, poems, hymns, games and vignettes classifying them by genre in an album entitled Popular Booklets. Stories and Songs of Naples where the librettos are categorized as “brigantesque, historical, romance, of jokes, biblical, christological-evangelical, parthenographic, hagiographic, legendary, eschatological, catharmological, pedagogical and moral, of contrasts and facetious.”

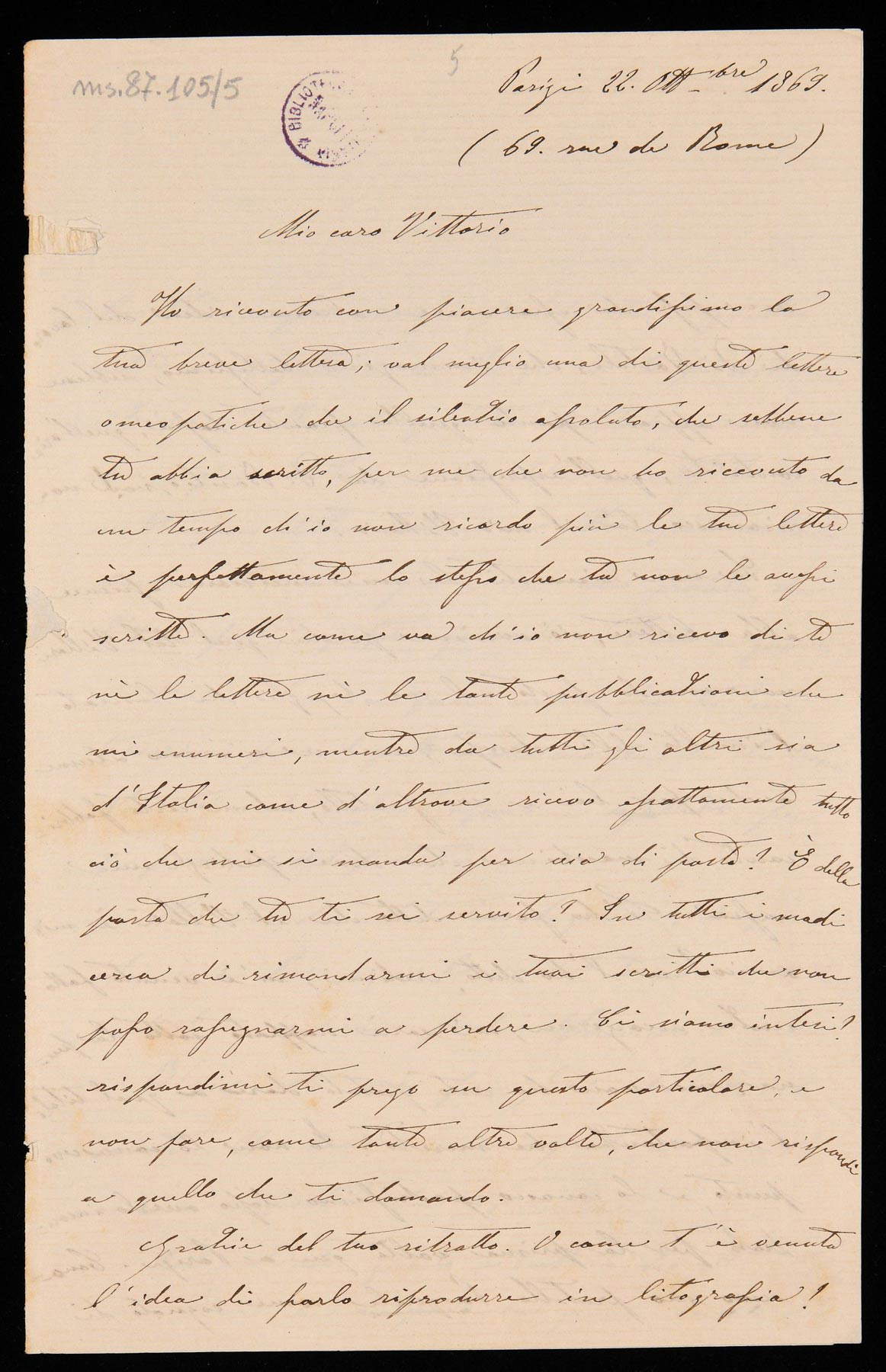

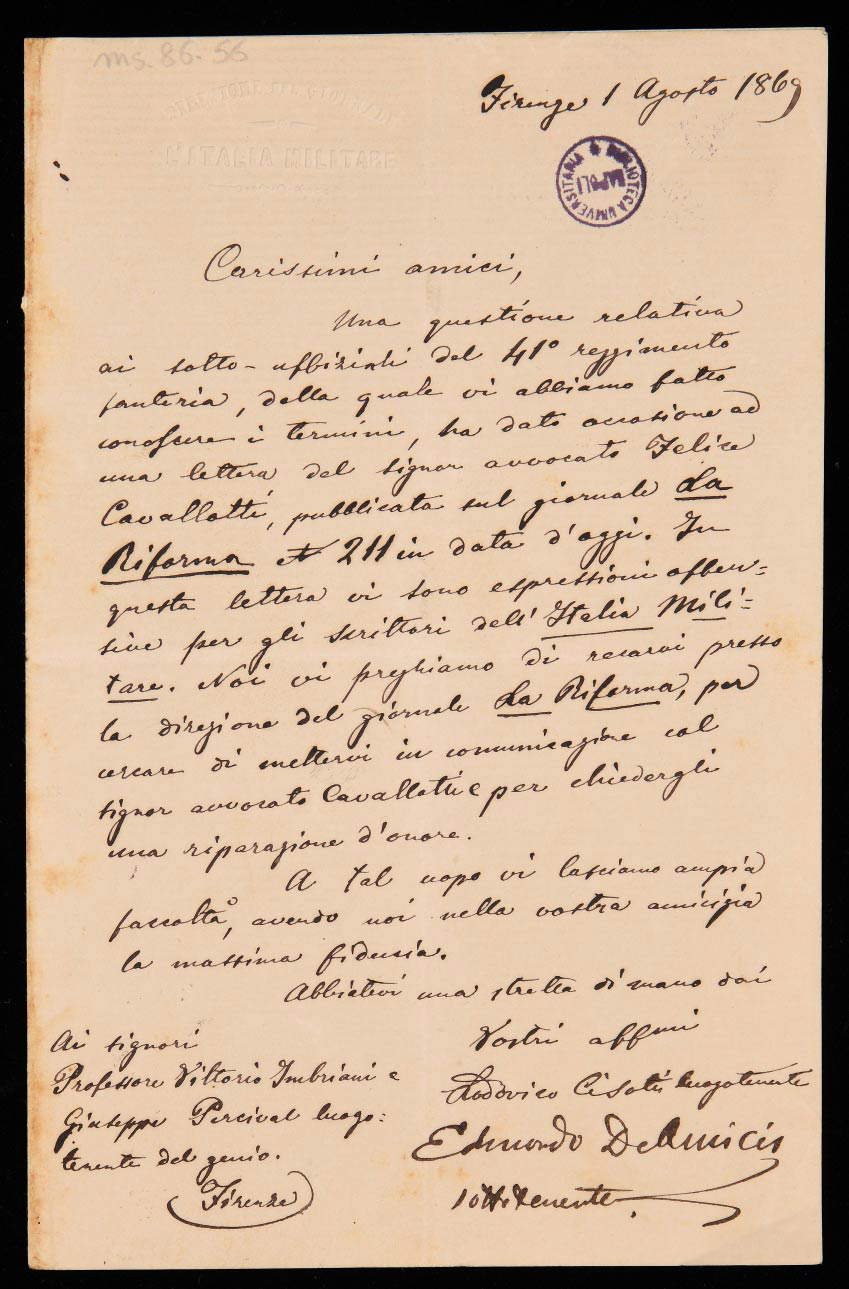

The Imbriani Fund also preserves the scholar’s copious correspondence, comprising 774 letters ranging from 1861 to 1882, and thanks to which it is possible to study in depth, in addition to the relations he had with the intellectuals of the time, also his temperament, his personality, his passions: it emerges, the Library explains, “an intellectual, with an impetuous character, a decisive edge, always at the center of fierce disputes, literary, political and even journalistic battles.” Some of the most interesting exchanges include those with Antonio Casetti, who like Imbriani was a scholar of Neapolitan folklore and collaborated with him to trace Neapolitan songs, those with the painter Filippo Palizzi and the art critic Saro Cucinotta thanks to whom it was it was possible to reconstruct Imbriani’s interest in art, as well as the letter from Enea Piccolomini, an erudite and expert philologist of Greek literature who carried out interesting studies on the Biblioteca Medicea, and those of the German writer Ludmilla Assing, who knew Imbriani during his Berlin years. The correspondence also contains a letter from Edmondo De Amicis in which he discusses matters of honor among journalists.

Recently, part of the Imbriani Fund is digitized and can be consulted on the Cultural Internet, catalogs and digital collections of Italian libraries. The material was then further enhanced, in May 2021, with a library exhibition entitled The Vittorio Imbriani Fund of the University Library of Naples. The popular librettos and the correspondence of a “Neapolitan misanthrope,” later translated into virtual form on the MOVIO platform.

The University Library of Naples

The origins of the University Library of Naples (BUN) date back to the seventeenth century, when the viceroy of Naples, Pedro Fernández de Castro, Count of Lemos, enacted a reform of university studies that provided the impetus for the opening of the university library: the library was established on November 30, 1616, a year after the opening of the new Palazzo degli Studi, where the library had also found a home. Later, the library, in 1777, was moved to the Jesuit Maximus College at the Savior, and in the early 19th century, with the suppression of monastic orders decreed in the Napoleonic era, it was enriched with many volumes from monastery libraries. After the Restoration and the return of the Bourbons to the throne of Naples, the library was reborn on December 4, 1816, as the Biblioteca dei Regi Studi, established by a decree of King Ferdinand IV of Bourbon: it would be opened to the public shortly thereafter, in 1827. Further enrichment of the collections took place after the Unification of Italy, when numerous scientific funds entered, the Dante collection donated in 1872 by Alfonso della Valle di Casanova, and the Imbriani Fund itself, which came to the Library in 1891. Damaged during World War II (some precious cinquecentines were lost during the conflict) and restored after the Irpinia earthquake of 1980, the Library still has asede in the former Jesuit college, in a place steeped in history: suffice it to say that the current reading room hosted, in 1848, the first assembly of the Neapolitan parliament after the 1848 revolution.

Today, the holdings of the Naples University Library number about one million books, to which 148 manuscripts are added (of particular relevance are the Imprese ovvero Stemme delle famiglie italiane by Gaetano Montefuscoli, one of the most valuable manuscripts in the BUN), 464 incunabula (including the 1465 Lactantius Sublacensis, the Neapolitan Aesop edited by Francesco del Tuppo in 1485, and an edition of the Divine Comedy illustrated by Sandro Botticelli, published in 1481, as well as the first Greek edition of Homer, printed in Florence in 1488), and about 4.000 cinquecentine. The BUN also possesses 300 Bodonians including a very rare copy of Giovanni Gherardo De Rossi’s Scherzi poetici e pittorici, a celestine paper copy of Vincenzo Imperiali’s Faoniade, not recorded in any repertory, and an Aminta by Torquato Tasso from 1789. Also of particular value is the Dante collection donated in 1872 by Alfonso Della Valle di Casanova, which also includes a Neapolitan print of the Commedia from 1477 and the first edition of the Academici della Crusca dating from 1595. Prominent among the scientific collections are the section of German medical periodicals, consisting of about 70 titles, and bequests from various professors of the Neapolitan university such as Filippo and Carlo Cassola and Raffaele Napoli (chemistry), Oronzo Gabriele Costa (paleontology), Filippo De Filippi and Francesco Briganti (natural sciences), and the two collections of pamphlets on comparative anatomy in the Panceri Fund and mathematics in the Battaglini Fund.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.