The richest and most abundant of all the albums of drawings by Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (Fuendetodos, 1746 - Bordeaux, 1828): this is Cuaderno C, which art historian Enrique Lafuente Ferrari called “the most personal” and a work that “largely reflects Goya’s reactions to the absolutism of Fernand after the return of the king from France.” As is well known, Goya had a conspicuous and frequent activity as a draughtsman, and he assembled his sheets into several notebooks: Cuaderno C, recently published in its entirety by Skira in collaboration with the Prado Museum in Madrid, originally contained 133 numbered sheets composed between 1814 and 1823. Of these 133 sheets, 120 survive, all of which are part of the collection of the Prado Museum, while the remaining thirteen are scattered in various collections around the world: 71 and 128 are part of the collection of the Hispanic Society of America, 88 is in the British Museum, 78 is in the Getty in Los Angeles, and 11 is in a private collection. Eight are missing: 14, 15, 29, 56, 66, 72, 110, and 132, which therefore remain unknown.

Like other notebooks by Goya, Cuaderno C has lost its original binding: the only notebook by the Spanish painter to preserve it is the so-called Quaderno italiano, whose drawings were made during the artist’s trip to Italy between 1771 and 1772. The others were all dismembered after Goya’s death, for commercial purposes: in fact, his heirs sold them and they went missing. This was the case with Notebook A (the Cuaderno de Sanlúcar), Notebook B (the Cuaderno de Madrid), Notebook D(Cuaderno de viejas y brujas, “Notebook of old women and witches”), Notebook E(Cuaderno de bordes negros, “Notebook of black margins”), Notebook F and the so-called “Bordeaux Notebooks,” or G and H. Cuaderno C has been preserved substantially intact because in 1866 the intermediary Ramón Garreta y Huerta, who looked after the business interests of the artist’s nephew, Mariano Goya, sold to the Museo de la Trinidad an album with 186 drawings, taken from the Sanlúcar and Bordeaux notebooks, along with the 120 drawings now in the Prado: the sheets came to the Madrid institution following its merger with the Museo de la Trinidad.

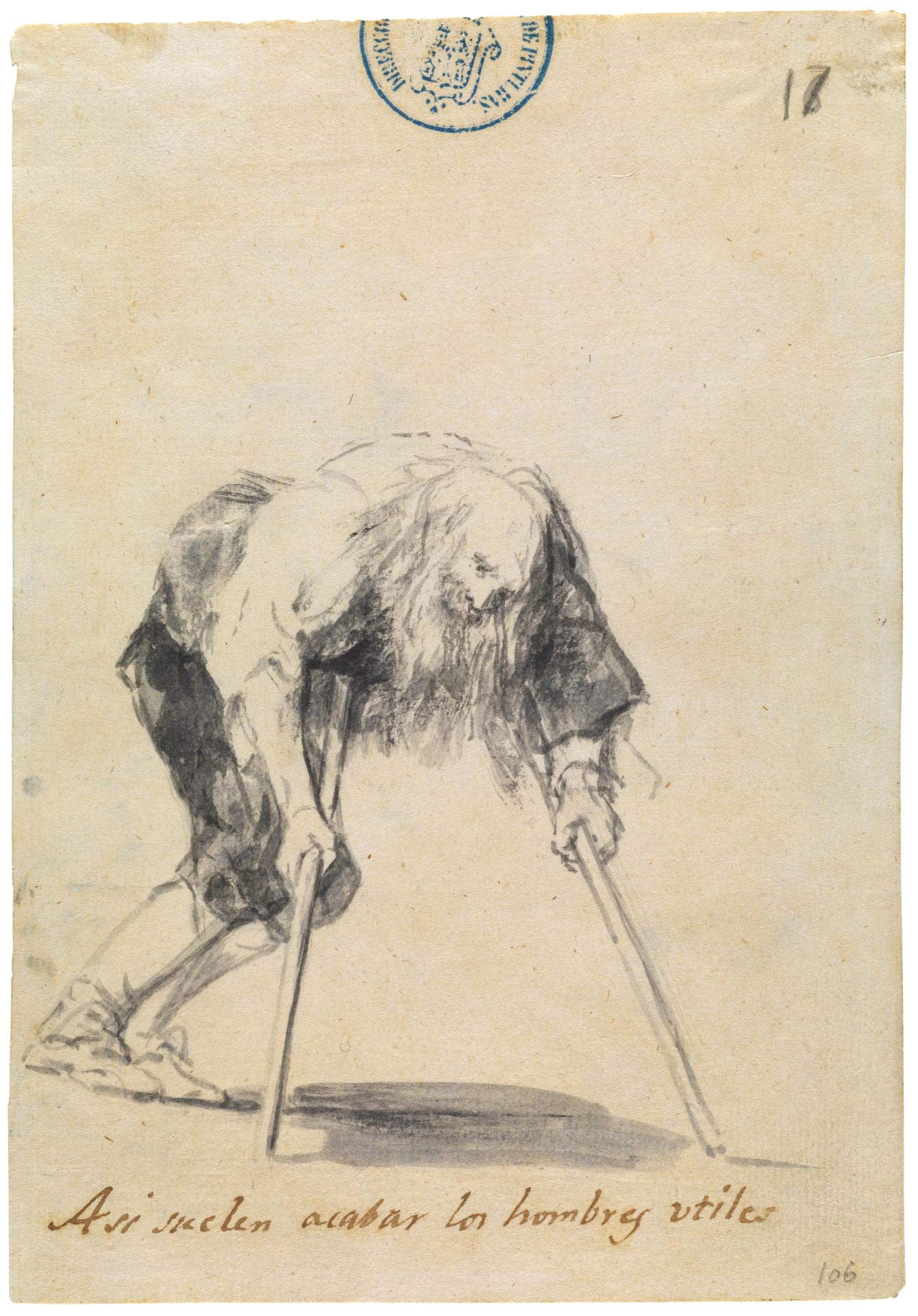

Cuaderno C is probably Goya’s most important both because of the wide variety of themes it covers, since different aspects of the daily life of the time enter the drawings collected in this album, and because it allows those who leaf through it to derive fairly precise ideas about what Goya thought about the reality of his time. There are drawings that depict convicts convicts of the Inquisition and thus address the theme of the fierce harshness of living conditions in prisons, still others that criticize the habits and customs of the monks, others related to the aftermath of the Spanish War of Independence, the longest of the Napoleonic wars, which was fought between 1808 and 1814, and several address the theme of the conditions of the elderly. One drawing that might well summarize Goya’s intentions is No. 17, accompanied by a caption (as is the case in almost every sheet) that reads Así suelen acabar los hombres utiles (“This is how useful men usually end up”), a touching image of a shaky elderly man barely holding on to two crutches, forced to beg: one of Goya’s many denunciations of the misery and social injustices of his time. The “usefulness” to which the artist refers in the caption is probably that rendered by the man during a past war, but also that which he could have guaranteed to society if the war had not forced him to be unable to work: the conflicts, which called to the front so many Spaniards torn from their families, their lands and their activities, produced many invalids who, no longer useful to society as they were unable to work, were forced to beg. These were very live concerns and the subject of debate in Goya’s time, between those who believed that war was necessary and therefore sacrifice was its inevitable implication, and those who questioned the consequences of war on the population. On the same tones is even the album’s first drawing, number 1, which depicts a beggar accompanied by the caption “Por no trabajar,” which can be rendered in Italian as “Because I cannot work,” since “por” in Spanish introduces a complement of cause.

|

| Francisco Goya, Francisco Goya, Asi suelen acabar los hombres utiles, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 17 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 206 x 142 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Por no trabajar, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 1 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

Another of the themes addressed by Goya in Cuaderno C is that of the consequences of theInquisition ’s actions after the end of the war, when it began a harsh repression against the so-called afrancesados, or Spaniards who had supported France’s occupation of Spain because they saw the ideals of the Enlightenment as a possible source of redemption for their country. Goya also supported the French side, and as a result of some vicissitudes discussed below, in 1824 the artist decided to go into exile in France, where he ended his existence. And since there are many drawings devoted to the Inquisition (which played a key role in the repression), the prisons and the torture to which prisoners were subjected who ended up in the hands of the inquisitors, scholar Juliet Wilson-Bareau has recently proposed that Cuaderno C also be given a distinctive name as it is for several other albums, and be called the “Notebook of the Inquisition.” For example, among the most horrific drawings is 91, Muchos an acabado así (“Many ended up like this”), which shows an execution with the garrote, an instrument that was invented and employed precisely in 1820s Spain for death sentences and consisted of a chair fitted with an iron collar that was tightened around the neck of the condemned man to strangle him. All drawings from 85 to 114 are referred to as those of the inquisition group, since they all depict people being tortured or killed by the inquisitors.

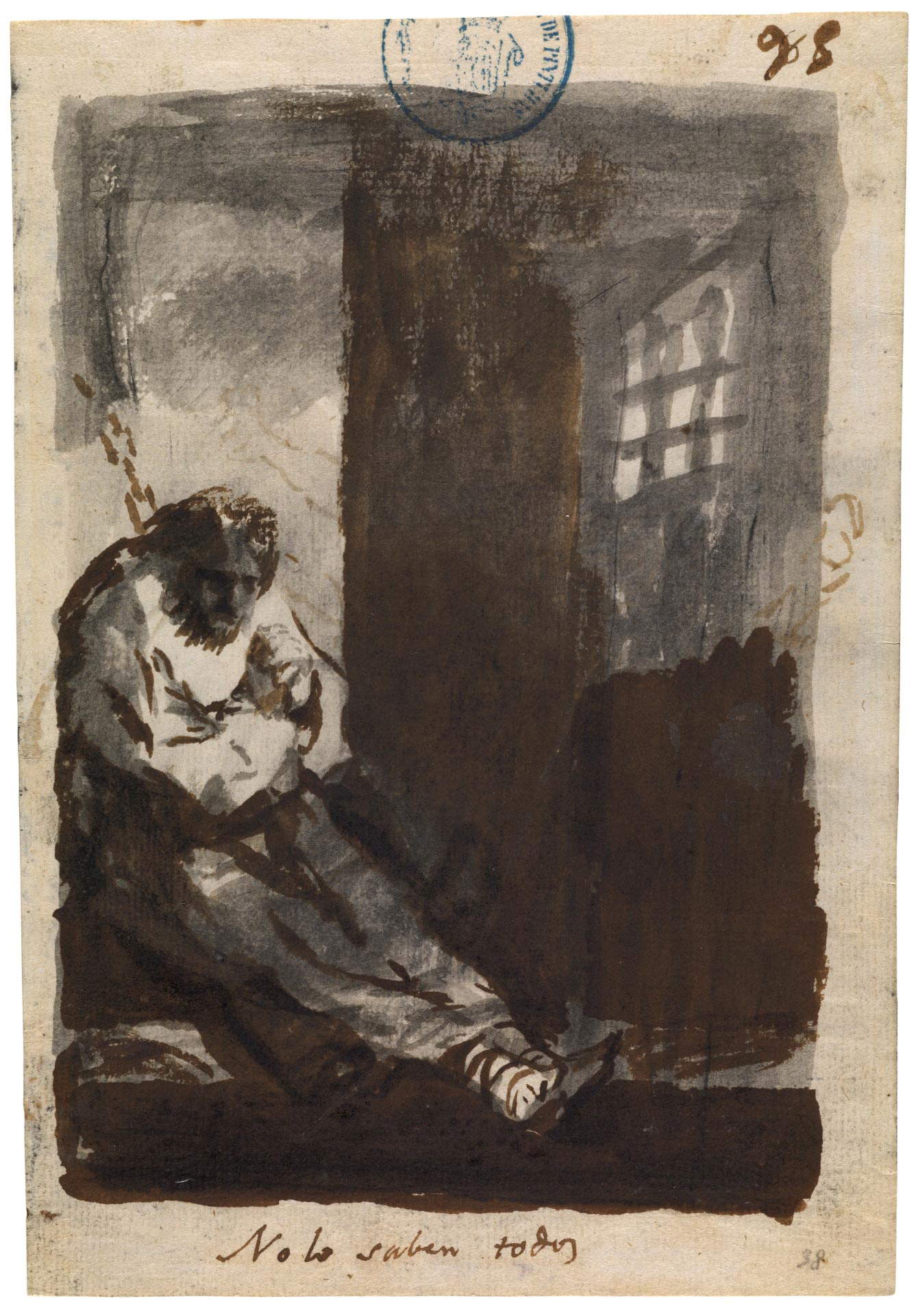

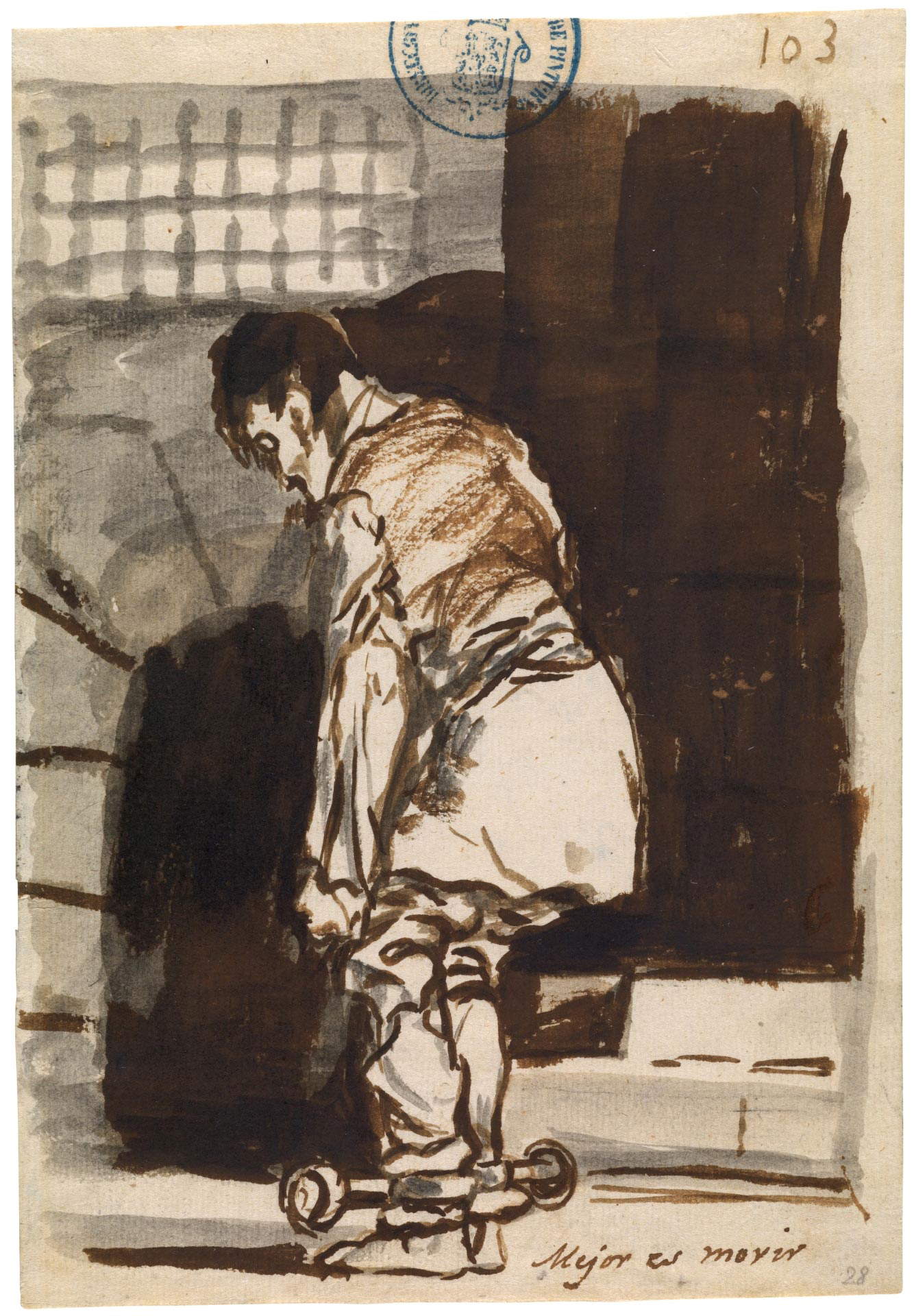

The inhumane conditions of the condemned are described with ferocity in drawings such as 95(No lo saben todos, “Not everyone knows”), which depicts a prisoner tied to a chain, with the title referring to the fact that probably few people knew the conditions of the prisoners, the 101(No se puede mirar, “You can’t see”), an image of an elderly man hanging upside down and tortured, or the eloquent drawing 103, Mejor es morir (“It is better to die”), in which Goya depicts a prisoner forced to stand with shackles blocking his ankles, or 87(Le pusieron mordaza por que hablaba, “They gagged him because he spoke”), where the prisoner is moreover depicted wearing the typical uniform of prisoners of the Inquisition, who were often required to wear the corosa (a long, pointed, ridiculous-looking headdress used to humiliate the condemned) and the sanbenito, a tunic that covered the chest and part of the legs while leaving the arms uncovered, and on which the reason for the condemnation was usually written. And then there is a bitterly ironic drawing, 114, with a desperate condemned man on which hangs the caption Pronto serás libre, “Soon you will be free.”

Art historian José Manuel Matilla, a Goya specialist who has extensively analyzed the Cuaderno C sheets, argues that the drawings of the Inquisition group demonstrate a certain familiarity with the ideas of historian Juan Antonio Llorente (Rincón de Soto, 1756 Madrid, 1823), who wrote an important Historia critica de la Inquisicion en España y America: “the ideological coincidence between literature and drawings,” Matilla writes, "induces us to think that Goya, as he had done previously for the Caprichos, addressed these themes by taking as a starting point the descriptions contained in the texts, and then later developed some images in which he shapes a critical vision, of atemporal and universal character, on the disproportion of punishments, the injustice of torture and the brutality of the death penalty."

|

| Francisco Goya, Muchos han acabado así, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 91 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, No lo saben todos, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), folio 95 (watercolor and charcoal on laid paper, 205 x 143 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, No se puede mirar, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), folio 101 (watercolor and charcoal on laid paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Le pusieron mordaza por que hablaba, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), folio 87 (watercolor and charcoal on laid paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Mejor es morir, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), folio 103 (watercolor and charcoal on laid paper, 205 x 143 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Pronto serás libre, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 114 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

Then there are some drawings, believed to be a few years later than those of the Inquisition, where the artist extols freedom, justice and reason: it is likely that these works date from the period of the so-called Liberal Triennium (1820-1823), the period in which Spain experienced a liberal government established following the uprising of Colonel Rafael del Riego against King Ferdinand VII, who was forced to reinstate the Constitution of Cadiz, promulgated in 1812 during the French occupation and then revoked by the sovereign as soon as he returned to the throne after the French were repulsed. However, the fragile liberal government that initiated a reformist policy aimed at ending the period of Ferdinand VII’s absolutism lasted barely three years: when Ferdinand VII, thanks to the intervention of the French, managed to defeat Riego at Jaén (the colonel was later executed), the old regime was restored, which moreover did not spare new repressions, so much so that the ten years that followed are known in historiography as the “nefarious decade”: Goya himself, as mentioned above, was among those who had to repair abroad.

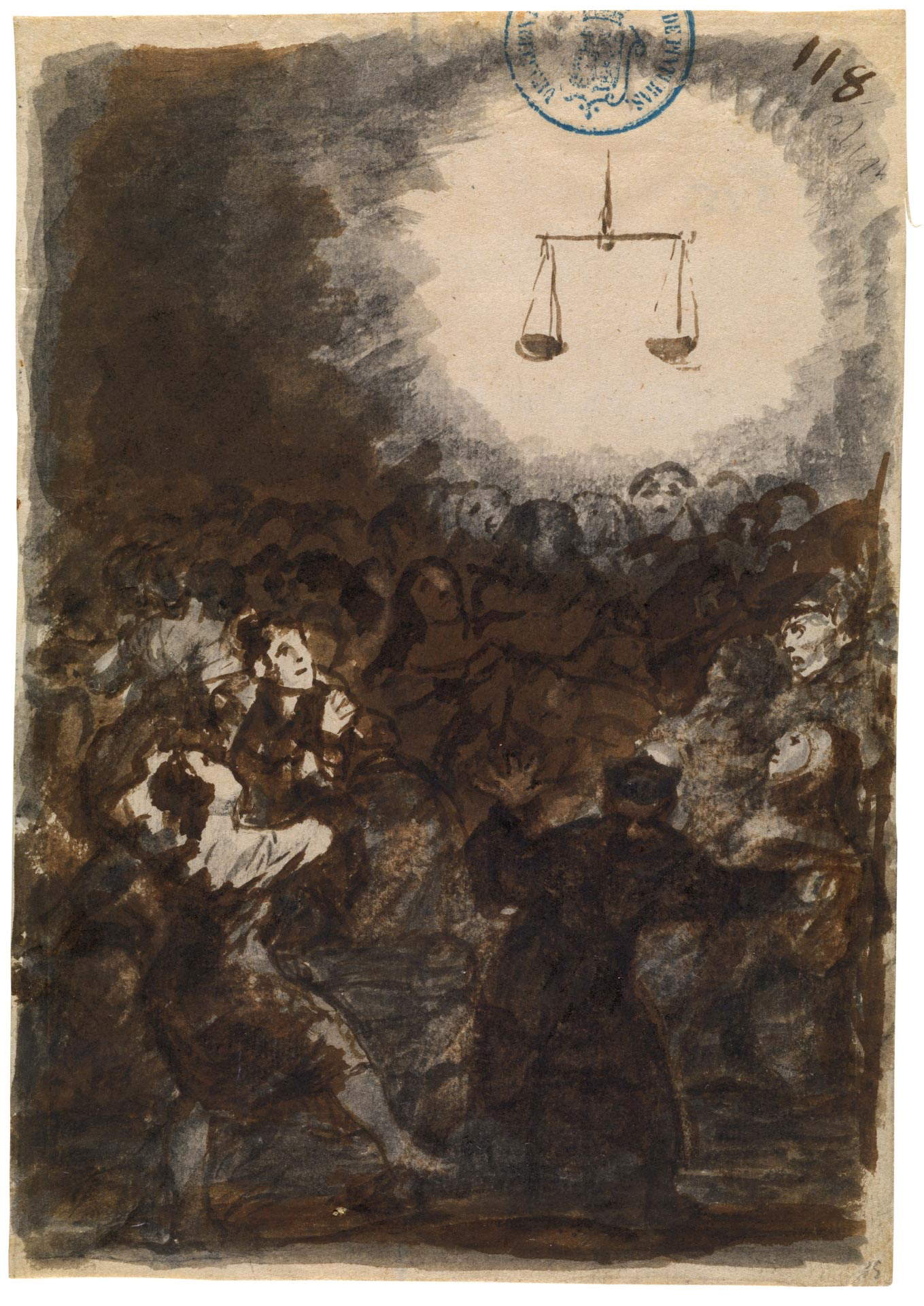

In the final part of the album, therefore, there are several allegorical drawings on positive themes. The first in the series is either 115, Divina libertad, with a man kneeling and invested by the deified light of freedom, or 116, Dure la alegría (“Hard the cheerfulness”), which depicts a group of people intent on drinking and celebrating, and then again 118, No a todos conviene lo justo ("Not to all conviene lo just o"), where a scale appears in the sky avvota by a dazzling halo of light that almost blinds the indistinct crowd at its feet, between those who take cover and those who try to look on in wonder, since for too long justice in Spain has been lacking.

|

| Francisco Goya, Divina Libertad, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 115 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, Dure la alegría, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), folio 116 (watercolor and charcoal on laid paper, 205 x 144 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

|

| Francisco Goya, No a todos conviene lo justo, from Cuaderno C (1814-1823), sheet 118 (watercolor and charcoal on virgin paper, 205 x 143 mm; Madrid, Museo del Prado) |

Scrolling through the sheets of Cuaderno C is, in essence, like entering the painter’s soul at the time of those troubled upheavals that Spain experienced in the early nineteenth century: one traverses the artist’s anguished feelings, his impatience, his concern for the plight of the humble and those affected by the repression of the Fernandan regime, his disappointment, and his hope for a brighter future. “It has been hypothesized that Notebook C,” Matilla wrote in the essay accompanying the publication of the album by Skira and the Prado Museum, “was a kind of graphic diary in which Goya illustrated all his concerns, particularly those concerning the fate of the most miserable and marginalized individuals, those who in one way or another suffered the economic, social and political consequences of the postwar period, the victims of circumstances with whom the now elderly artist, deaf and in a precarious financial and political situation because of his own ideas, could largely identify. The heartbreak that pervades these sheets is perhaps an expression of the artist’s personal suffering, and the pessimism that shines through the drawings is that of a man deeply disgusted with his surroundings.”

Cuaderno C has been described as an epitome of Goya’s art, since this collection of sheets includes almost all the themes of his art: society and its problems, the inquisition and its tortures, faith in a better tomorrow, fantasy, and freedom. We do not know for whom these drawings were intended, but it is likely that Goya made them for his own personal use: this is what both Matilla and Manuela Mena, another scholar who analyzed Cuaderno C, speculate. Personal drawings, because if they had ended up in the wrong hands Goya would have risked ending up like the characters he drew. And that is why they are works to be viewed with a special eye. “These proofs,” Matilla explained in fact, "demand an active observer-reader, pondering their composition and meaning. The captions by the author’s own hand, which often serve as titles or commentaries on the various images, are revealing, since the double meaning they play on invites reflection on the real intention that animates them. In this sense, the word and the image form an inseparable whole and must be received in unison. Moreover, words often build a trait dunion between the various drawings, concatenating works that acquire their actual meaning when they are ’read’ in succession, like the pages of a book. Only in this way is it possible to grasp the sequences and thematic groups conceived by Goya in the course of the elaboration of Notebook C."

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.