The historical and archaeological art of Mariana Castillo Deball, object biographer

“My work intersects with archaeology, ethnology or history, although the discourse I create is neither linear nor a narrative history, but consists only of interrupted futures. It is an idea of a set of temporal deviations.” These are the words of Mariana Castillo Deball (Mexico City, 1975), who succinctly defined her art in such terms in a 2014 interview. The exploration of history, and in particular the relationship we have with history (and consequently, our interpretation of the past and our interaction with what happened), is a constant in her production. In order to derive a particularly iconic idea of this interest, we need to look at one of her latest works, Hypothesis of a tree, first exhibited at the 2016 São Paulo Biennial and re-presented to the Italian public, albeit in a reduced form, at the 2017 edition of Artissima, at the booth of the Pinksummer gallery in Genoa.

The artist, attracted to the work of biologists, wondered what the link might be between paleontology and the practices of phylogeneticists, the researchers who study the origin and evolution of organisms. In other words: what is the relationship between fossils, tangible imprints of living beings, remnants of organisms that lived tens, hundreds or millions of years ago, and the abstract nature of genetic studies? And again: what is the relationship between humans and different species? Mariana Castillo Deball therefore set to work together with a biologist friend, Gabriela Aguileta, to create a work that would try to provide an answer to these questions. The idea was to build a phylogenetic tree, that is, an outline of the lineage of the different living species, that would be three-dimensional, in order to allow the public to delve into its branches, as if to make them touch the history of evolution. In order to carry out her undertaking, Mariana Castillo Deball made visits to natural history museums, such as the one in Solnhofen, southern Germany (the artist lives and works in Berlin), located in the immediate vicinity of a site of Jurassic fossil finds, or at paleontological sites themselves, such as the Crato formation in Brazil, a Lagerstätte, or fossil accumulation field, among the most important in the world for its extension and the variety of species found in its layers.

The artist then studied the fossils with the help of several paleontologists, and began to make reproductions of them using the tracing technique, imprinting the surface of the finds with the use of ink on Japanese paper. The drawings obtained were then placed on large sheets of paper and arranged, like banners, on a large bamboo cane structure, which reproduced the pattern of a phylogenetic tree: seen from above, it took the shape of a large spiral. And the structure itself is an early intervention about the relationship between fossils and phylogenetics: the artist assumes that evolution does not stop with man, but continues over the millennia, and the spiral is meant to suggest to the viewer this idea of continuation that potentially lasts indefinitely. The height of the different branches of the tree, on the other hand, is connected to the age of a species: the lower the branch, the older the corresponding stage of evolution. One of the most curious aspects of the installation is that man is symbolized by drawings of urban elements of the city of São Paulo. In the São Paulo Biennial catalog, critic Fábio Zuker wrote that "by juxtaposing human constructions and fossils of animals and plants, memories of natural and urban landscapes, and gathering them on the same storyline, the artist puts the ideas of time and space in perspective, proposing a new narrative about the history of extinction, survival and transformation." In other words: we represent but a small portion of nature, but it is also true that our reasoning allows us to work out structures to classify nature itself. Almost a kind of reminder of our responsibility.

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Hypothesis of a tree (2016; bamboo, tracings in black ink on Japanese paper, dimensions variable). Ph Credit Leo Eloy / Estúdio Garagem/ Fundação Bienal de São Paul. Courtesy São Paul Biennial |

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Hypothesis of a tree (2016; bamboo, tracings in black ink on Japanese paper). Ph Credit Leo Eloy / Estúdio Garagem/ Fundação Bienal de São Paul. Courtesy São Paul Biennial |

|

| Merle Greene, Recalculation of a Palenque Sarcophagus (1963; black ink recalculation on rice paper, 44.5 x 64.1 cm; San Francisco, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco) |

The tracing technique with which Mariana Castillo Deball executed her work is connected to the history of her country, Mexico. Among the pioneers of tracing as a tool of study was archaeologist Merle Greene (Miles City, 1913 - San Francisco, 2011), who used the technique to perform surveys at Mayan sites in Central America: during her decades-long career as a scholar of Mayan antiquities, Merle Greene produced thousands of reliefs, which are of fundamental documentary importance, partly because of the fact that several monuments have since deteriorated due to the action of time and weathering, or due to looting by smugglers of ancient artifacts. Mariana Castillo Deball has always been fascinated by the figure of Merle Greene, and has never made a secret of it. The U.S. scholar can be considered the direct inspiration behind a project mounted at the San Francisco Art Institute in 2016, entitled Feathered Changes, Serpent Disappearances: a work in which the artist’s focus shifted to objects, analyzed in their capacity as tools for understanding history. Part of the work consisted of a display of objects found (and often abandoned) in the archives of the museum hosting the exhibition: fragments of forgotten artifacts, documents, casts. Underlying it was the idea that the history of archaeology itself introduces an additional layer on top of the history tout court, the one that should be told by archaeological finds.

The problem is that even the findings are not in themselves sufficient to clearly, incontrovertibly and completely reconstruct history. The interpretation of history can therefore only be subjective, and part of that interpretation necessarily rests on chance, on possibility. However, possibility, according to Mariana Castillo Deball, could also be a way of interpreting history. In Feathered Changes, Serpent Disappearances, archaeology merged with the music theory of John Cage (Los Angeles, 1912 - New York, 1992), a composer who introduced random techniques in the writing of his works so as to circumvent his own will and minimize the possibility of subjective interpretation of the music itself: moreover, the project’s title referred to a composition by Cage, entitled Changes and Disappearances, and to the feathered serpent (“feathered serpent” in English) of Mesoamerican religions. Mariana Castillo Deball had been openly inspired by John Cage’s aleatoric techniques to exhibit at the San Francisco Art Institute the objects found in the archives along with tracings of Mayan monuments, reproductions, ceramics, maps and miscellaneous objects, to suggest to the viewer the idea that possibility helps to compare opposites, fosters dialogue and reduces the possibilities of “dealing with memory in a schizophrenic way.” The result was a kind of large archaeological “collage” that served almost as an invitation to reconsider the way we confront our past, and conversely to embrace a less rigid, less schematic, more open view of history.

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Feathered Changes, Serpent Disappearances (2016; installation, various dimensions). Ph. Credit San Francisco Art Institute |

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Feathered Changes, Serpent Disappearances, detail. Ph. Credit San Francisco Art Institute |

To ancient Mesoamerican cultures, and thus to Mariana Castillo Deball’s historical roots, referred an important 2013 work, Tamoanchan, a term for the cosmic tree of Central American cultures: it was a reconstruction of the mural of Tepantitla, a work depicting a tree at the foot of which sits an anthropomorphic figure, variously identified. “The two halves of the tree,” the artist herself explained, “have opposite elements. On one half are shells, snails, fish, all elements of water and cold. The other half has flowers, minerals and warm elements. On the cold branches we can see insects rising, butterflies flying to the top. On the warm branches there are spiders weaving their web, and one of them is clearly coming down hanging from a thread in the center of the picture. The spider descends; but it is important not only because it is going down. Pasztory provides us with another clever association: the spider is connected to dust and drought. The forces ascending and descending in the tree are connected with the agricultural cycle. We still find in this image, both in the figure and in the tree, the struggle of opposing forces.” The tree, in fact, stands halfway between heaven and earth, and is presented with two twisted trunks of different colors and populated by different animals and plants. Some scholars have wanted to see, in this dualism, the opposition between male and female: however, despite the fact that this element has been abundantly clarified by numerous studies, the overall meaning of the figuration is still subject to interpretation. Thus Mariana Castillo Deball’s interest in the diversity of worldviews and history, which arise where an “object survives beyond itself,” returns: “I focus on this problem and see how different people have approached this object from their different points of view. Maybe it’s an exercise in concentration. I think it is also finding myself in what I think is right or real or correct. I adopt the position of the object and follow its path.”

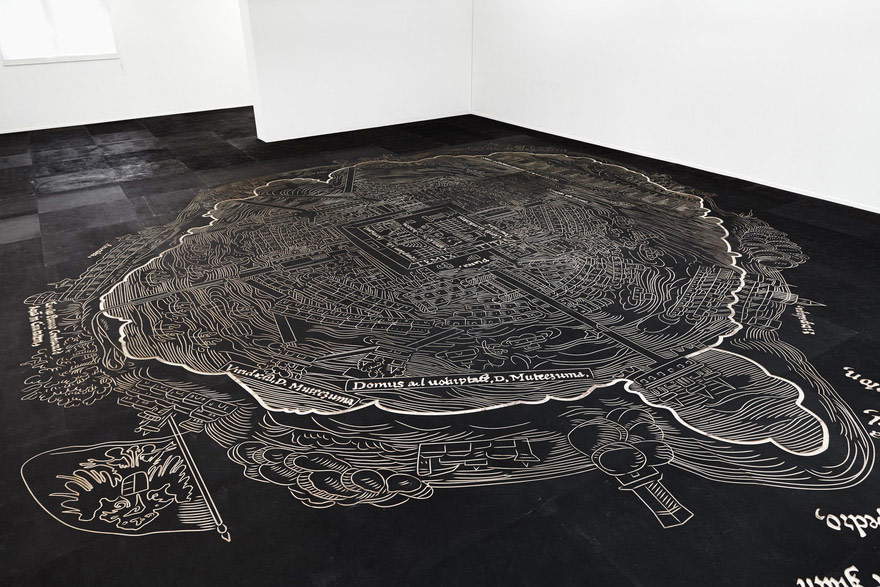

To make this dropping into the interpretation of the object evident, Tamoanchan was conceived as an image to be displayed on the floor of the exhibition space: a kind of map that the visitor could walk through, an allusion to the fact that Tepantitla’s work can be interpreted as a kind of celestial map of the regulating forces of the universe. This was not the first time that Mariana Castillo Deball used the floor of a gallery or museum as a “support” for her own achievements. In Berlin in 2014 and the following year at the Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain in Sérignan, France, the Mexican artist exhibited a work titled Nuremberg Map of Tenochtitlán, which reproduces the 16th-century map of Tenochtitlán, the ancient capital of the Aztec empire destroyed in 1521 by the conquistadors. The map, sent to Spain by Hernán Cortés that same year, represented the first image of the city that Europeans got to know: it would later be published three years later in Nuremberg. It was a map that highlighted two different visions of Tenochtitlán: that of the locals, who had depicted it with their symbols and references to their history, and that of the Europeans, who saw it as a rich and flourishing city to be conquered. Another invitation to preserve memory: that of a civilization overwhelmed by the arrival of conquerors.

Also as part of the Sérignan exhibition, Mariana Castillo Deball had proposed another of her most important works, ¿Quién medirá el espacio, quién me dirá el momento? (“Who will measure the space, who will tell me the moment?”). The project was intended to explore the concept of survival, another recurring theme in the artist’s production: ¿Quién medirá el espacio, quién me dirá el momento?, whose title is taken from a lyric by one of Mexico’s greatest poets, Xavier Villaurrutia, is a series of totems made from modern Atzompa ceramics, in forms and subjects that recall the centuries-old traditional pottery, typical of the town located near Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. The result is a repertoire that forms a varied vocabulary of themes and symbols, in which present and past merge, where the boundary between the history of pottery and that of the potter becomes blurred (in a perspective that recalls Carlo Ginzburg’s microhistory ), and which offers the possibility of investigating the relationship with archaeology (of which the work intends to disseminate a changing vision that is not subject to standing firm on acquired orders) and with historical heritage, the ways in which the past survives and the forms in which it reappears, as well as the stories that the past is able to tell and the explanations that it is able to provide. A repertoire that, starting from a single motif, expands on multiple levels. It is a bit like what happened in the game of Cadavre exquis of the Surrealists, an image evoked by Mariana Castillo Deball herself: one starts from a base, adds more elements, even very different ones, and activates mechanisms that allow one to plough deep spaces through unprecedented readings. “The main exercise,” said the artist, “was to develop a story that unfolded through the centuries, and a story that happened in one day instead. The result was on the one hand the story of the origin of the universe in a hundred years, and on the other the origin of the universe in one day. But the two stories are almost identical. And then there is the story of the potter’s journey, from the time he wakes up at dawn to prepare the clay to the time he finishes working the clay, fires it, and then sells his wares so he can buy grain to eat. Each character becomes pottery, and we arranged them in columns that reach to the ceiling, so visitors can surround the stories and read them from the bottom up or from the top down.”

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Tamoanchan (2016; wood engraving, dimensions variable; exhibition photograph at Pinksummer Gallery, Genoa). Ph. Credit Pinksummer Gallery, Genoa |

|

| Tepantitla mural in a reproduction preserved at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City. Ph. Credit Thomas Aleto |

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, Nuremberg map of Tenochtitlán (2013; wood engraving, dimensions variable; exhibition photograph at Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain in Sérignan). Ph. Jean-Christophe Lett |

|

| Audience on Nuremberg map of Tenochtitlán. Ph. Jean-Christophe Lett |

|

| Mariana Castillo Deball, ¿Quién medirá el espacio, quién me dirá el momento? (2015; four ceramic columns; photograph from the exhibition at the Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain in Sérignan). Ph. Jean-Christophe Lett |

Mariana Castillo Deball’s merit is to confront us with our knowledge in order to overturn seemingly established points of view. Phylogenetics becomes matter to reflect not so much on the past as on the future of evolution, the map of the capital of the Aztec empire confronts us with the responsibilities of our culture by providing an additional element of discussion for the reality of the present, the history of an object becomes part of universal history. Traditions, taken for granted acquisitions and ideological constraints fall before the power of its works. Despite the fact that these works are largely composed of minute objects, often fallen into oblivion, seemingly insignificant.

After all, Mariana Castillo Deball is, to use aneffective definition by critic Peter Yeung, a “biographer of objects.” Her art “digs through the history of a thing, meticulously examines it, analyzes and verifies its origins, its changes in meaning, almost like a kind of social archaeologist turned artist.” And for her,contemporary art is a useful means of analyzing the historical complexity of objects, it is itself a tool for studying, questioning, reasoning about what has been, it is a practice that draws from different disciplines, it is a means of discussion that dialogues with history: and knowing history, placing oneself in a critical position with regard to memory and the past, is a fundamental requirement for living in the present. This seems to be what her works tell us.

Mariana Castillo Deball was born in Mexico City in 1975 but lives and works in Berlin. She studied at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México in the Mexican capital and completed her studies in the Netherlands, in 2003, at the Jan van Eyck Academie in Maastricht. In 2004 he won Holland’s Prix de Rome and in 2009 he won the Ars Viva prize of the Kulturkreis der deutschen Wirtschaft, a major award given annually to the best young artist living and working in Germany, in the past also won by artists such as Marina Abramovic, Georg Baselitz and Wolfgang Tillmans. He exhibited at Manifesta 7 in 2008, the Venice Biennale in 2011, Documenta in 2013, the Berlin Biennale in 2014, and the Liverpool and São Paulo Biennales in 2016. His exhibitions have been held at the Kunsthalle in St. Gallen (2009), the Museum of Latin American Art in Long Beach (2010), the Chisenhale Gallery in London (2013), Hamburger Banhof in Berlin (2014). In Italy, his works are in the collections of the Castello di Rivoli.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.