The great masters of Spanish painting in the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville

The center ofAndalusia, Seville is certainly one of the best-known and most sought-after destinations for tourists coming to Spain, and the city is strongly anchored in its traditions, which are moreover a major attraction. Seville is also an important center of art thanks to the splendid monuments that characterize its streets and squares, including the Cathedral, built his a pre-existing mosque, now the largest Gothic church in Spain and one of the largest in the world, the Giralda which is its bell tower, built in the 12th century as a minaret, and numerous other monuments including royal and noble palaces. But Seville was also, along with Madrid and Valencia, among the main centers of radiating figurative art in Spain, giving rise to one of the most long-lived and prolific in the Iberian state, which counted valiant painters, including Juan Sánchez de Castro, Francisco Pacheco, Francisco de Zurbarán, Diego Velázquez, and Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, to name but a few of the most famous.

To learn about this long season, which invested several centuries, a visit to the Museum of Fine Arts is a must: an extraordinary museum in terms of the quantity and quality of the works on display. Often referred to by guidebooks as the largest museum in Spain after the Prado, the Museum of Seville in fact departs from the famous museum in the capital, as the collection nuclei are quite different: not a European collection with big names from Italy, France, Germany and so on, but a coherent collection, strongly rooted with the territory.

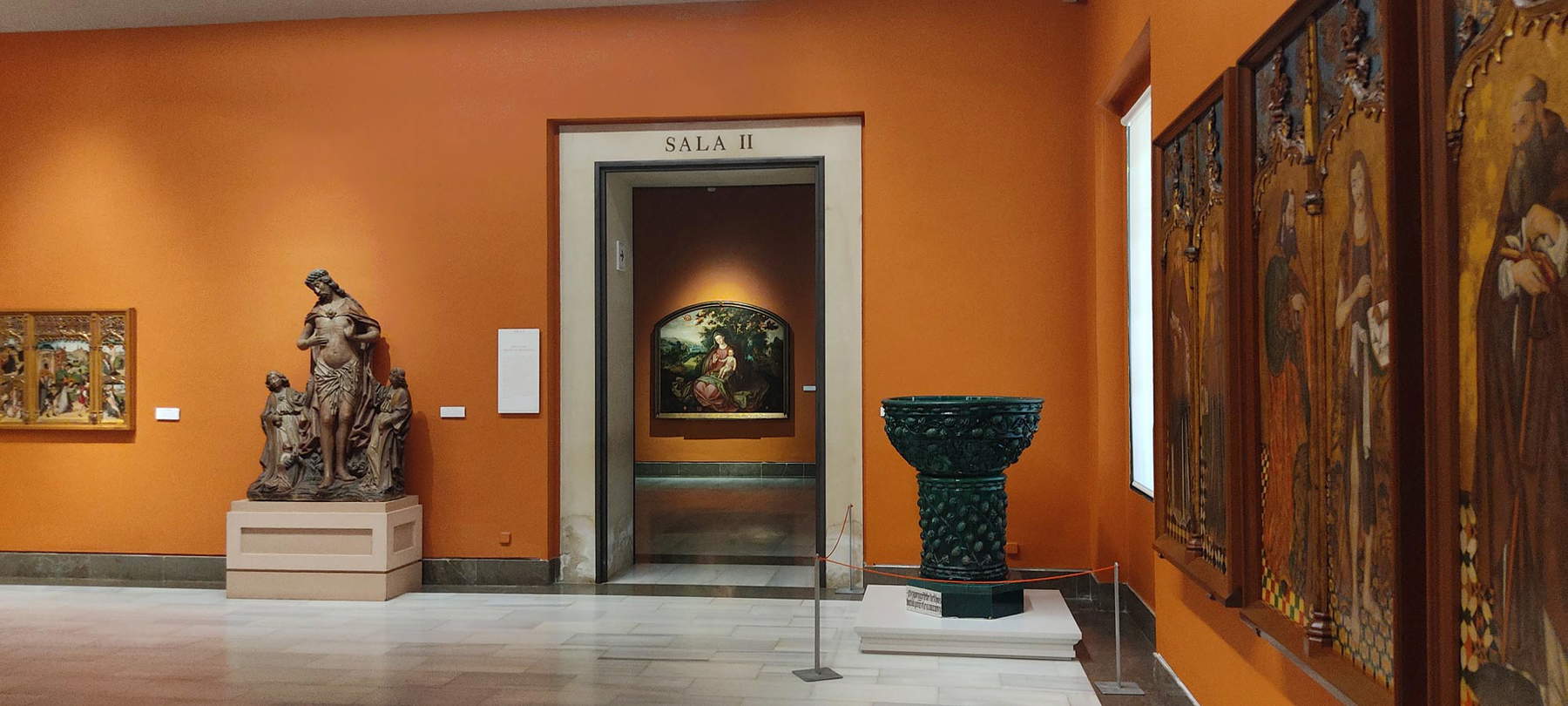

The Museum of Fine Arts of Seville was founded as a picture gallery by Royal Decree of September 16, 1835, at a time when there was the secularization of the large estates belonging to various religious companies that were being forfeited by the state, and therefore, as happened in Italy, to find a home for the numerous cultural assets from disused churches, convents and oratories, as well as to try to stem the continuous hemorrhaging of works that ended up on the private market to be purchased by foreign collectors. The chosen venue fell on the old convent of Merced Calzada, commissioned by Ferdinand III in the 13th century after wresting Seville from the Moors, and then remodeled over the centuries, especially around 1612, shaping up as one of the most magnificent examples of Andalusian Mannerism.

The

The The room with the works of

The room with the works of The room with the works of

The room with the works of The arrangements in the

The arrangements in the The arrangements in the room dedicated to

The arrangements in the room dedicated to

The museum is located in Plaza del Museo, dominated by a bronze statue of the painter Murillo made by sculptor Sabino Medina, a replica of which is also placed in the vicinity of the Prado Museum in Madrid. The main façade, sober and majestic, is embellished by an arch set on columns; above it is a large niche inhabited by the figures of the Virgen de la Merced, San Pedro Nolasco, founder of the Order of Mercy, and King Jaime I of Aragon, its protector.

The interior is a precious and refined space, far from the chaos of the city, enriched by several cloisters connoted by lush greenery and colorful ceramics, for the production of which the city of Seville is famous. The tour begins with a selection of painters and sculptors active in the city in the 15th century, a period to which the beginning of the Seville school is traced. In particular, the exhibition is focused around two figures: first that of Juan Sánchez de Castro (active in the second half of the 15th century), known as the “patriarch of Sevillian painting,” since he was able to emerge among Andalusian Gothic painters thanks to his openness to Mediterranean influences, making his paintings veined with grace and sweetness. Works belonging to artists close to his style are still thought of on gilded backgrounds, where attention to detail is still of the Flemish brand

Another nodal figure is Pedro Millán (Seville, active between 1487 and 1506), an artist also active in the Cathedral and founding father of the Sevillian sculptural school, whose splendid Lament Over the Dead Christ in polychrome terracotta, in which the Gothic style is contaminated with a refined expressive naturalism, is exhibited.

Among the founders of new trends should also be mentioned the Tuscan Francisco Niculoso Pisano (Pisa, 15th century - Seville, 1529), a painter and sculptor of majolica active in Seville in the first two decades of the 16th century, who had the fundamental role of spreading in Spain the historiated majolica decorated with grotesques, and the polychrome bas-reliefs taken from the Della Robbia, whose first work on Spanish soil is preserved in the church of Sant’Anna in Triana, a neighborhood still famous today precisely for its production of majolica.

The museum tour then leads to the artists’ room of the 16th century, a time of great wealth and splendor for Seville, thanks to its monopoly role with trade with the American colonies. The great wealth attracted Flemish and Italian artists and their works to the city, including the extraordinary Last Judgment by Maarten de Vos (Antwerp, 1532 - 1603), connoted by a multitude of contorted bodies.

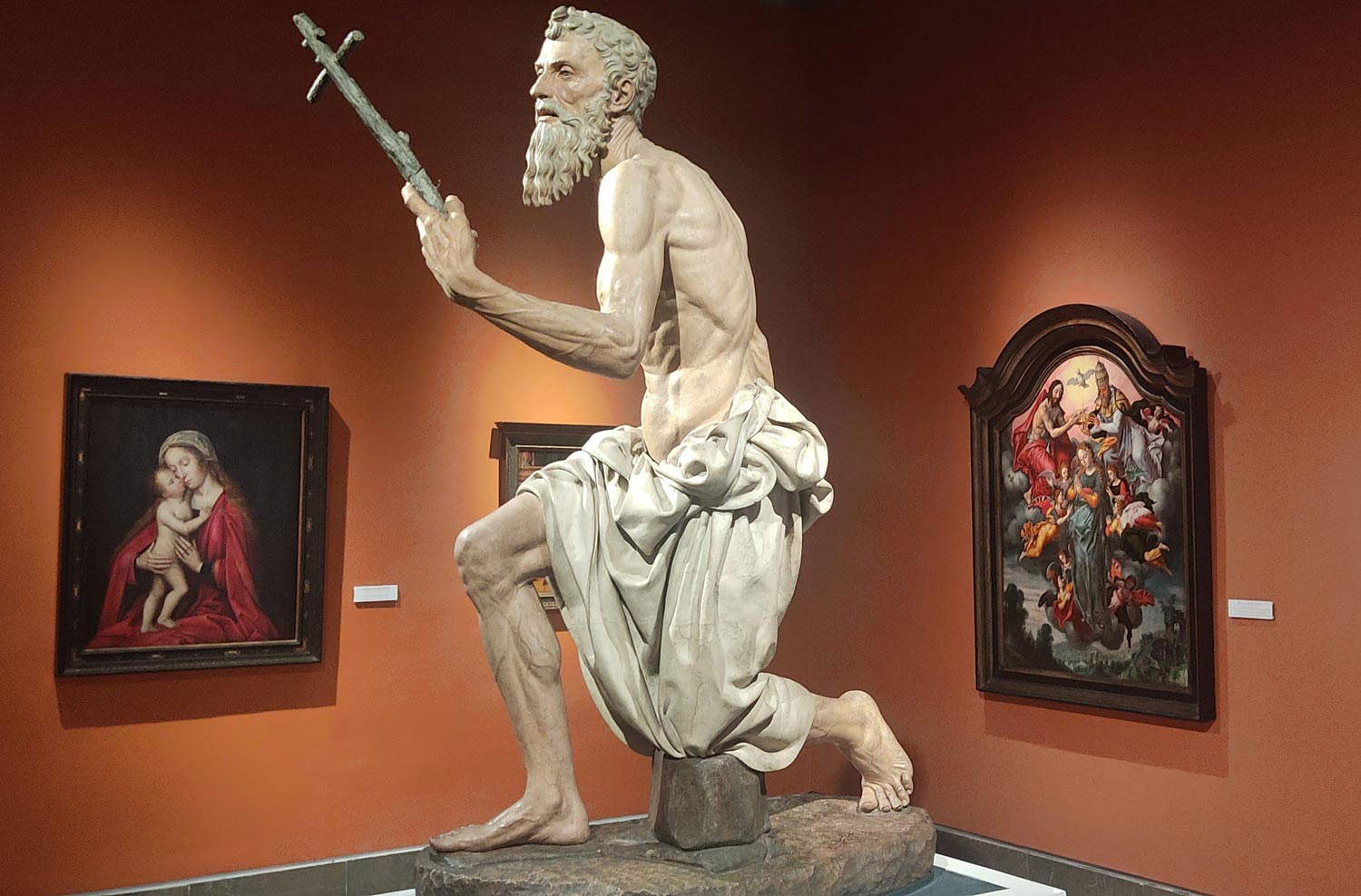

Extraordinary in quality are two sculptures by the Florentine Pietro Torrigiani (Florence, 1472 - Seville, 1528), known for his aversion to Michelangelo, whose criticism unleashed his wrath, which resulted in a punch against the famous artist, whose nose he broke, which was deformed for life. The punch cost Torrigiani his exile from Florence and the beginning of his wanderings through Italy first, then London and finally Seville, where, however, he had no better luck. Having become an in-demand sculptor, Torrigiani apparently had not improved in his manners; in fact, according to Vasari, in 1522 after destroying with a chisel a statue of the Madonna made for a prestigious patron who did not want to pay him adequately, he was imprisoned for iconoclasm by the Spanish Inquisition, dying, it seems, the same year in prison amid hardship and suffering.

Returning to the museum itinerary, other valuable works include a Calvary painted by Lucas Cranach (Kronach, 1472 - Weimar, 1553) and a Portrait of his son by El Greco (Domínikos Theotokópoulos; Candia, 1541 - Toledo, 1614) in the room. Among the locals, a prominent role is played by Alejo Fernández (Cordova, 1475 - Seville, 1545), who introduced some Renaissance formulas into Sevillian art, as can be inferred in theAnnunciation, present in the museum, constructed with great perspective rigor and interest in ancient architecture.

Thereafter, Iberian art became increasingly emancipated from Nordic models and turned instead to Italian examples. The Mannerist season is marked by a few personalities, including the painter and treatise maker Francisco Pacheco (Sanlúcar de Barrameda, 1564 - Seville, 1644). Although sometimes considered a mediocre painter because of his such static images, he cannot be denied a fundamental role within the Sevillian school: in fact, he was a teacher and father-in-law of Velázquez, who married his daughter, and he kept other talented painters in school, including Alonso Cano and Francisco López Caro. He knew how to instill these great artists into the new season of Naturalism, which unlike in Italy with Caravaggio and the Bamboccianti, was not the end to which their creative efforts tended, but merely a means of telling the Gospel message with immediacy.

Pacheco’s pupils along with other important names will be the generation of painters known as the grand masters, men born between 1590 and 1610 who will produce some of the greatest masterpieces of Spanish art. With them opened the great Baroque season.

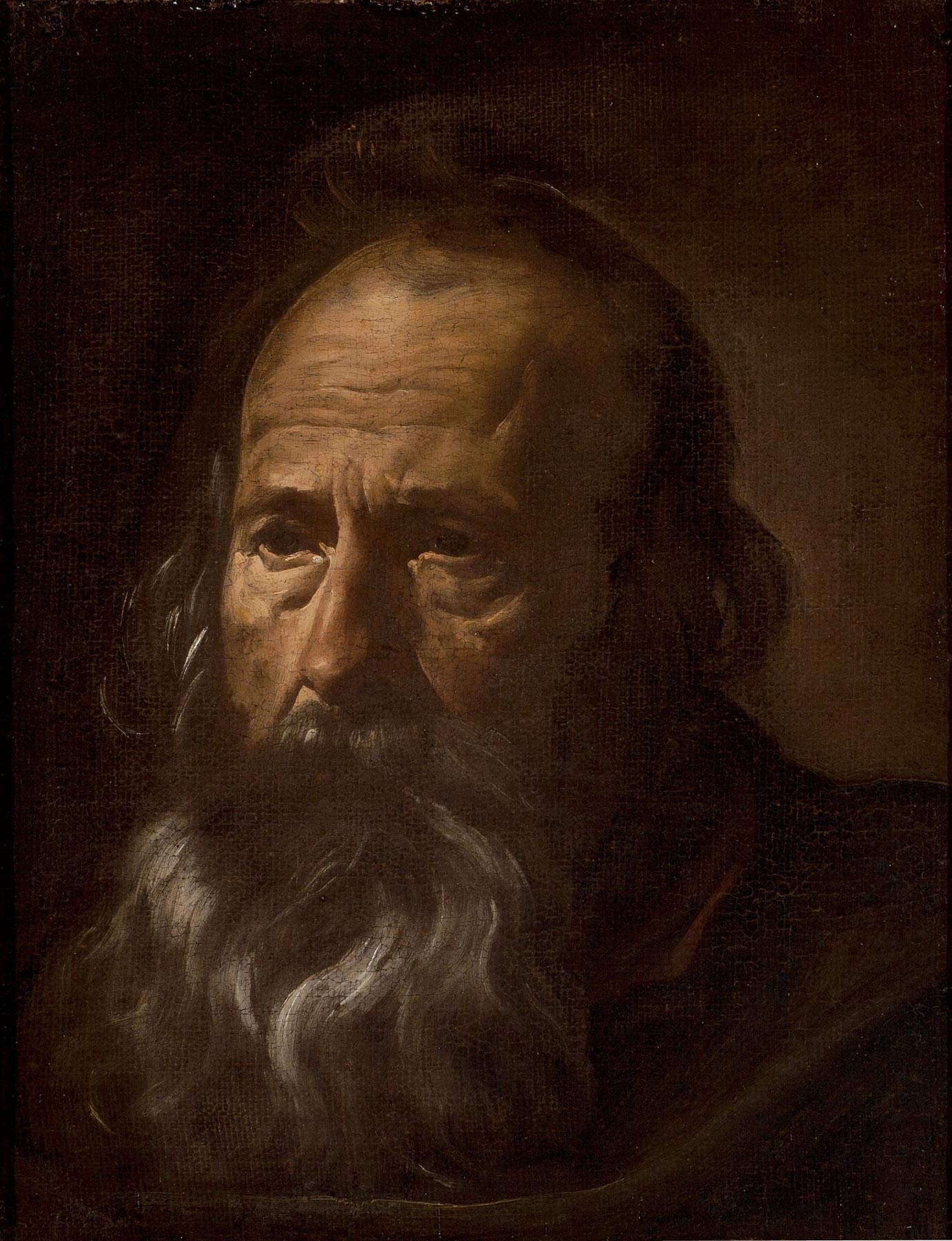

By Diego Velázquez (Seville, 1599 - Madrid, 1660) only two works are preserved in the museum, the Head of an Apostle, perhaps recognizable with St. Paul, and the Portrait of the Religious Don Cristóbal Suárez de Ribera, for that matter while still young he moved to Madrid to become painter to the King.

And if in the second work the treatment of the face does not appear realistic, this is perhaps attributable to the fact that it would be a posthumous portrait, while in the head of the prince of the apostles, on a dark brown preparation typical of the Seville productions of the young Velázquez, the painter with a centered choice of tones achieves a head bursting with life and energy.

Pacheco’s other pupil, Alonso Cano (Granada, 1601 - 1667), was also one of the protagonists of the siglo d’oro: he was the most classical among this cohort of artists, and he gave life to an art tending toward an ideal beauty through balance and moderation that led him to eschew certain solutions of naturalist painting. The St. Francis Borgia, an early work by the painter, shows some interest in the gloomy painting of Jusepe Ribera.

Born near Valencia in 1591, Jusepe de Ribera, known as the Spagnoletto (Xàtiva, 1591-Naples, 1652), is the artist least associated with the city of Seville among the great masters of the Baroque season, but a number of his works are preserved in the museum, including a painting of St. James the Greater, a replica of which is kept in the Palazzo Barberini in Rome. Finally, among the great masters, mention should also be made of Francisco de Zurbarán (Fuente de Cantos, 1598 - Madrid, 1664), a native of Extremadura but educated in Seville, is alsohimself represented with some extraordinary altar machines, where simplicity that eschews learned artifice and an almost obsessive attention to realism and crisp, synthetic volumes have always made him a highly regarded painter. Perhaps the artist’s most worthy works on display here are the Crucifixion and theApotheosis of St. Thomas Aquinas.

The last decades of the century, under the reign of Charles II, represent the season of the mature Baroque, years when Spanish painters had a chance to catch up with what was happening in the rest of Europe. The certainly most famous name of the period is that of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Seville, 1618 - Cádiz, 1682), whom it is precisely in this museum that it is possible to get to know in depth thanks to the many works on display, so much so that the writer Richard Ford stated that “in Seville Murillo is admired in all his glory...a giant on native soil.”

Murillo’s works are displayed in the monastery’s old church, in the Latin-cross nave topped by a dome. The artist has long been considered among the most important Spanish painters, on par with Velázquez; in more recent times his value has been downplayed, to which the accusation of excessive sentimentality has been levelled. Murillo’s greatness, on the other hand, lies in his unsurpassed skill in religious storytelling, giving life to devotional images that even today have not lost their force and effectiveness, constantly renewing iconography and models to meet the liturgical needs of different patrons.

The museum does not stop at these golden centuries, and the 18th century is also worthily represented, which, however, like the fortunes of the country, had a time of decline. Among the finest essays are those by Domingo Martinez, who in great detail describes celebrations and floats passing through the streets of Seville. The 19th century, on the other hand, is marked by Romantic painting, which radiated from Seville throughout the country, with paintings of historical subjects as well as exotic and oriental themes. The itinerary also includes works by Goya and, and other authors of definite interest.

The Museum of Fine Arts of Seville is therefore an essential stop for the art lover who decides to visit the Andalusian city, and although far from the tourist flows (or perhaps because of it) the visiting experience allows a deep immersion in the history of Spanish art.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.