The foundation of the Mona Lisa and the mascara of Giorgione's Old Woman.

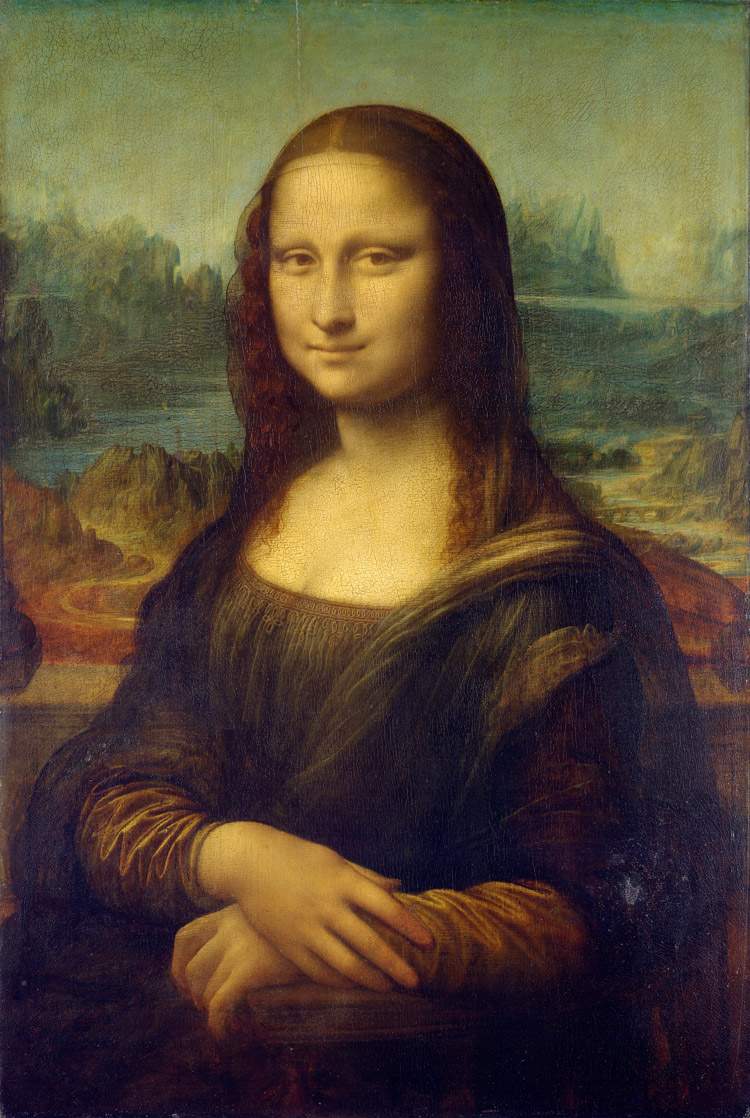

The most famous painting in the world is the Mona Lisa, yet no one has really seen it (fig. 1). In the sense that no one has seen it as it is under the thick layer of dirt and oxidized paint that covers it. Right now the woman’s skin has an amber tint, as if she had been integrally made up with heavy foundation; the sky is green, as are the mountains in the distance; everything is crystallized in a chromatic cocoon that does not correspond to the original setting. If it were not the Mona Lisa, the painting would have been restored long ago, not least because we are in a position to know almost exactly what it would look like should a judicious cleaning be carried out. For the past few years, in fact, a copy made within Leonardo’s workshop has resurfaced in the Prado’s warehouses in Madrid that shows the Mona Lisa in very different colors: the complexion is light, the sky blue, the sleeves red and not brown (fig. 2) In addition, thanks to the sophisticated non-invasive diagnostic techniques now available, there is so much information about the conservation status of the Parisian painting that we would be on the safe side. Why, then, does the Mona Lisa continue to remain in the appearance that time and ancient restorers have given it? The reason is very simple. Because, in the case of restoration, we would lose the image of the painting as we know it now: precisely the Mona Lisa. In short, what would happen is what happened following the restoration of Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. Impeccably cleaned up by Gianluigi Colalucci and his team during an intervention that lasted several years, they reappeared as Michelangelo had conceived them (fresh, clear, brilliant, plastic) but very differently from what we had been used to knowing them: that is, as Federico Zeri said, latte-colored. Controversy to no end ensued, with even prominent experts crying disaster foretold, irredeemable havoc. Thanks to such invectives these experts coagulated legions of hyper-orthodox followers unleashed in declaring absurdities. Imagining all this, the various directors of the Louvre up to now who have succeeded one another have not seen fit to destroy licona and expose themselves to controversies that in the case of the Mona Lisa would be even more furious.

|

| 1. Leonardo da Vinci, The Mona Lisa (oil on panel, 77 x 53 cm; Paris, Louvre) |

|

| 2. Leonardo’s workshop, Copy of the Mona Lisa (oil on panel, 76.3 x 57 cm; Madrid, Prado) |

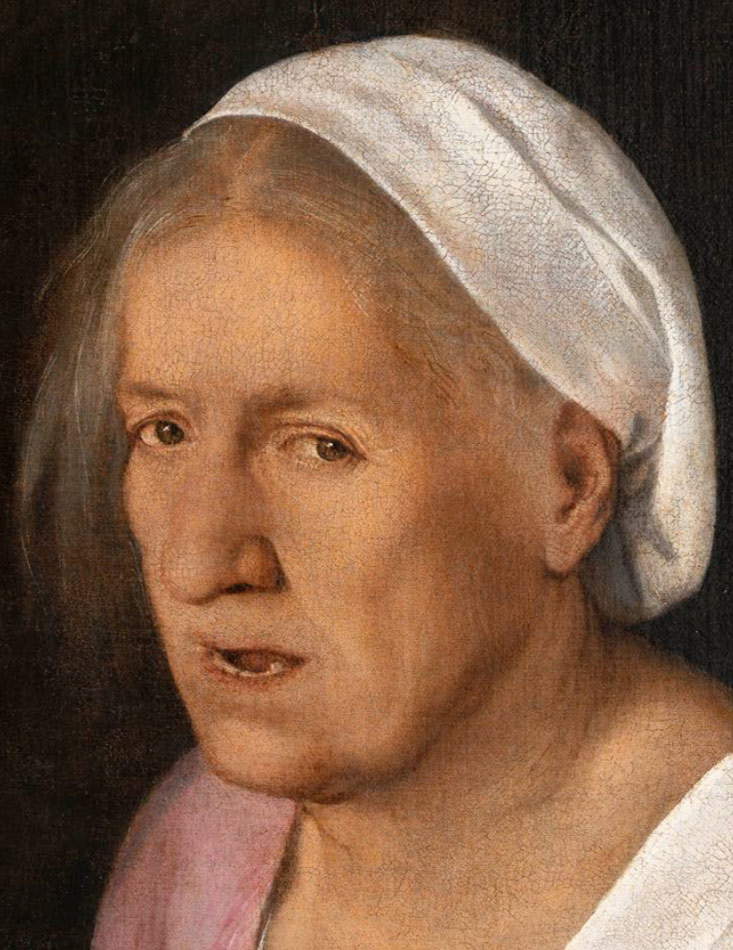

Differently reasoned are those who have taken responsibility for having what is no less fascinating and important a masterpiece than Leonardo’s Mona Lisa cleaned up: namely Giorgione’s so-called Vecchia at the Gallerie dellAccademia in Venice (fig. 3). After decades of study and analysis, the painting in 2018 was restored by Giulio Bono, with the advice of a committee of specialists who flanked the operations of historical verification, cleaning, pictorial reintegration and repainting. The result (in my eyes impeccable) was presented on September 24 at the Gallerie dellAccademia by the museum’s director, Giulio Manieri Elia, and Giulio Bono himself. The lecture opened a series of in-depth meetings on the painting that will see in October talks by the writer (on the 8th: on the subject), by Bernard Aikema (on the 29th: on conflicting interpretations) and in November those by Linda Borean (on the 12th: on the collecting affair) and finally by Janyie Anderson (on the 19th: on attribution and provenance). This is an opportunity for enthusiasts to be informed about the history of the painting, the certainties we have and the hypotheses that have been put forward and that can be put forward. But at this point the basis for reflection has changed: the painting is noticeably different from how it appeared before, when it was tarnished by oxidized varnishes, dirt and old restorations. The most paradoxical aspect is that now the Old Woman is a little less old, in the sense that in the course of the cleaning all those retouches that, for purely aesthetic reasons, had wanted to accentuate the age of the woman, who appeared dirty (the lincarnate was a very improbable tobacco color) and wrinkled (an Old Woman can only be so), were conveniently removed (figs. 4-5). However, one only had to look at the yellowishness of the cap and the fabric covering her shoulder to see that the original tone could only be very different, namely white.

|

| 3. Giorgione, La Vecchia, before restoration (painting on canvas, 68.4 x 59.5 cm; Venice, Gallerie dellAccademia). GAve photo archive - courtesy of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism, National Museum Gallerie dellAccademia, Venice. Ph. Matteo De Fina |

|

| 4. Giorgione, La Vecchia, macrophotographs of the eyes in the visible |

|

| 5. Giorgione, La Vecchia, macrophotographs of the eyes in UV |

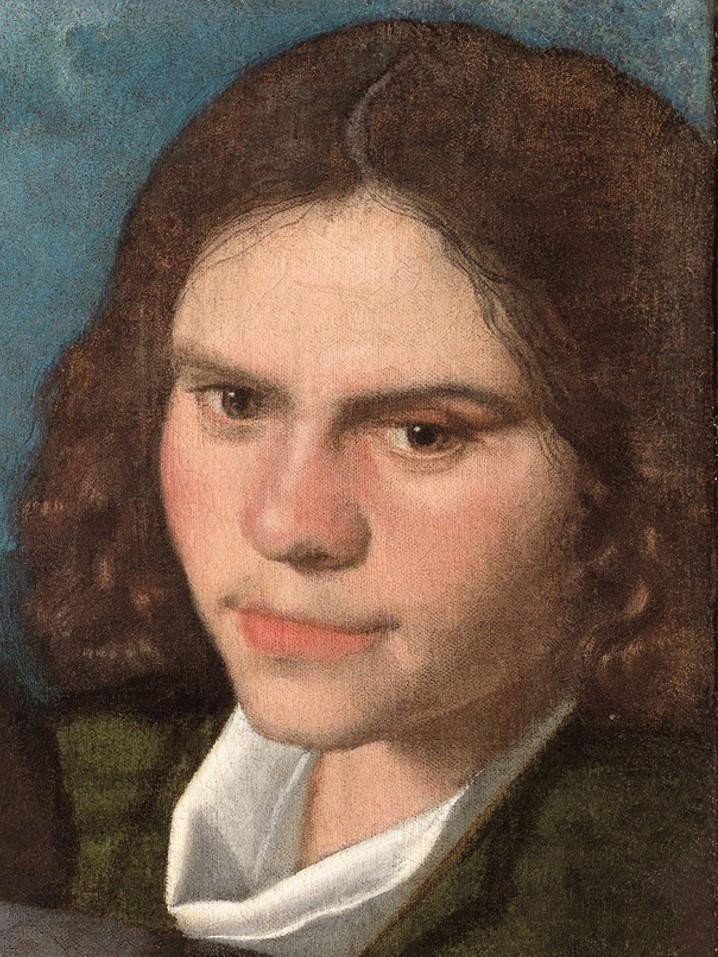

Now what seemed like a premonition of a Caravaggesque character is presented as a creature of the Venetian humanism of which Giorgione was an expression (fig. 6). She is a woman described with a chromatic range similar to that of the last Giovanni Bellini and the first Titian, of whom Giorgione was a kind of trait dunion. Variously dated by critics, the painting now seems well within the first five years of the century and ties in perfectly with the Castelfranco master’s only two other certain portraits later: the so-called Laura in the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the magnetic Man in the San Diego Museum. The result of theintervention thus legitimizes the full and final rehabilitation of works about which not a few scholars have expressed doubts about Giorgionesque authorship, starting with the Two Friends from the Palazzo Venezia Museum in Rome (figs. 7-8).

But who was this woman, the subject of such a ruthless and cruel portrait, so ostentatiously overlooked does she turn out to be? The extremely realistic nature of the interpretation rules out the possibility that this is a pure allegory, although the cartouche with the inscription COL TEMPO tends to turn her into a kind of emblem of the loss of youth, to which she seems to respond by manifesting herself, humbly, as she is. An answer had been offered in the early inventories reporting the painting in the Vendramin collection in Venice: the Mother of Zorzon by man di Zorzon. If so, thanks to Giacinto Cecchetto’s research, we would even be able to give her a name: Altadona di ser Francesco da Campolongo di Conegliano, widow of the notary Giovanni di Gaspare Barbarella da Castelfranco. And not only would we give her a name: in fact, a number of darchivio documents are available thanks to which a sketch of her biography can also be traced. In such a perspective, suggestions and hypotheses are thrown wide open: who could have been its first owner, if not the artist himself? How did it enter the collection of Gabriele Vendramin, who also owned the Tempest? And when? Who saw it in the 500s and 600s? How is it possible that it so resoundingly anticipated certain interpretations by Caravaggio and his followers, as well as Rembrandt, who also portrayed his mother several times? For those who want to know more, the lectures at the Gallerie dellAccademia are open to the public, by reservation only.

|

| 6. Giorgione, The Old Woman, after restoration |

|

| 7. Giorgione, La Vecchia, after restoration, detail of the woman’s face |

|

| 8. Giorgione, Two Friends, detail of the face of the young man in the background (oil on canvas, 80 x 75 cm; Rome, Museo Nazionale di Palazzo Venezia) |

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.