The Fondaco dei Tedeschi, a building of thirteenth-century origins overlooking the Grand Canal, next to the Rialto Bridge, stands at one of the nerve centers of central Venice, and is not only an architectural masterpiece and a symbol of the Serenissima’s mercantile past, but also a silent witness to the history that has shaped the city over the centuries. From a nerve center of international trade in the Middle Ages to a contemporary cultural and commercial hub, the Fondaco dei Tedeschi tells a rich and complex story that reflects the very essence of Venice.

The origins of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi(Fontego dei Tedeschi in Venetian) date back to 12th-century Venice, when the city established itself as a major maritime and commercial power in the Mediterranean. Venice was a bridge between East and West, a place where merchants of all nations met to exchange goods, ideas and culture. To facilitate these activities, Venice’s public administration had begun to open fondaci, multifunctional structures designed to house and control foreign communities dedicated to trade. Some had port functions, all were places of commerce, warehouses for goods, and could also house housing.

There are records of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi as early as the 13th century. And it came into being for the purpose of accommodating merchants from the Holy Roman Empire, a geographical area that included much of central Europe. These merchants, referred to generically as “Germans,” were crucial partners in the Venetian economy, particularly in the import of raw materials such as lumber, metals and fine textiles. The earliest records are between 1222 and 1225: the purchase by the City of Venice (then not yet a Republic) of the area on which the Fondaco dei Tedeschi would be built dates from this period. Of the ancient medieval building we know very little: the only known, sketchy image is from Jacopo de’ Barbari’s Map of Venice in which the fontego is depicted as a set of three buildings arranged around a courtyard. However, the map dates from the late fifteenth century, and by that time the original building had already been heavily transformed (a first fire developed here in 1318 and involved a reconstruction of the building).

A further violent fire, which broke out on the night of January 27-28, 1505, completely destroyed the structure of the Fondaco. The Republic of Venice, aware of the centrality of this building to the city’s economy, ordered its immediate reconstruction. In 1508, under the direction of the architect Antonio Scarpagnino, who took over from Giorgio Spavento (although the model was drawn up by another architect, Girolamo Tedesco, who was a member of the Teutonic merchant community: a personage of whom we know practically nothing, although a portrait of him executed by Albrecht Dürer perhaps remains, although of his identification we are not certain), a new Fondaco was built, larger and more sumptuous.

This Renaissance “version” of the Fondaco, the one we can still visit today, reflected not only the practical functionality necessary for a warehouse and residence for merchants, but also an aesthetic that was meant to impress visitors. The Fondaco dei Tedeschi thus appeared (and still does) as a quadrangular building with a large central courtyard. The structure, developed on four levels, responded to a rational organization of space. The first floor, with its large arcades, was dedicated to the goods warehouse. The upper floors, on the other hand, housed the offices and living quarters of the German merchants. The structure, over the centuries, has remained unchanged: the first image of the interior of the fondaco dates back to 1616 (an engraving by Raphael Custos) and we can easily verify how little has changed. However, the Fondaco dei Tedeschi remains, for several reasons, one of the most fascinating buildings in Venice at the time.

“As a whole, even looking at it superficially and based on the present factory, that is, on a building that is the result of substantial transformations from the original,” wrote scholar Elisabetta Molteni, “the Fondaco presents elements foreign to theVenetian architecture of the time especially in the solutions of the elevation (in the courtyard and in the organization of the facade), but at the same time it shows as many that are unequivocally rooted in the city’s architectural and building practices. The courtyard of the Fondaco is considered by all studies to be the most original element of the complex and the most problematic because no comparable structure would have existed in Venice at that time. It is not so much the existence of the court that creates a problem, since court buildings also show several by De’ Barbari and [...] even the ancient first Fondaco was organized around courts with loggias. Moreover, even in the fifteenth century, medieval eastern fondaci show this structure (witness, among others, Felix Fabri). The difference lies in the fact that the courtyard is configured as an antiquarian element that presupposes a very up-to-date knowledge of ancient architecture. [...] The salient elements of the courtyard are three: the extremely simple pillars (or rather the ’columnae quadrangulae’ following the Albertian lexicon) that support the arcades of the loggias; the system of diminishing arches and pillars in the different registers of loggias; and finally the L-shaped articulation of the corner pillar. It is these fundamentally the elements that make the Fondaco a problematic building in the panorama of Venetian architecture of those years and that have provoked a very rich debate among scholars about the possible author of this design.”

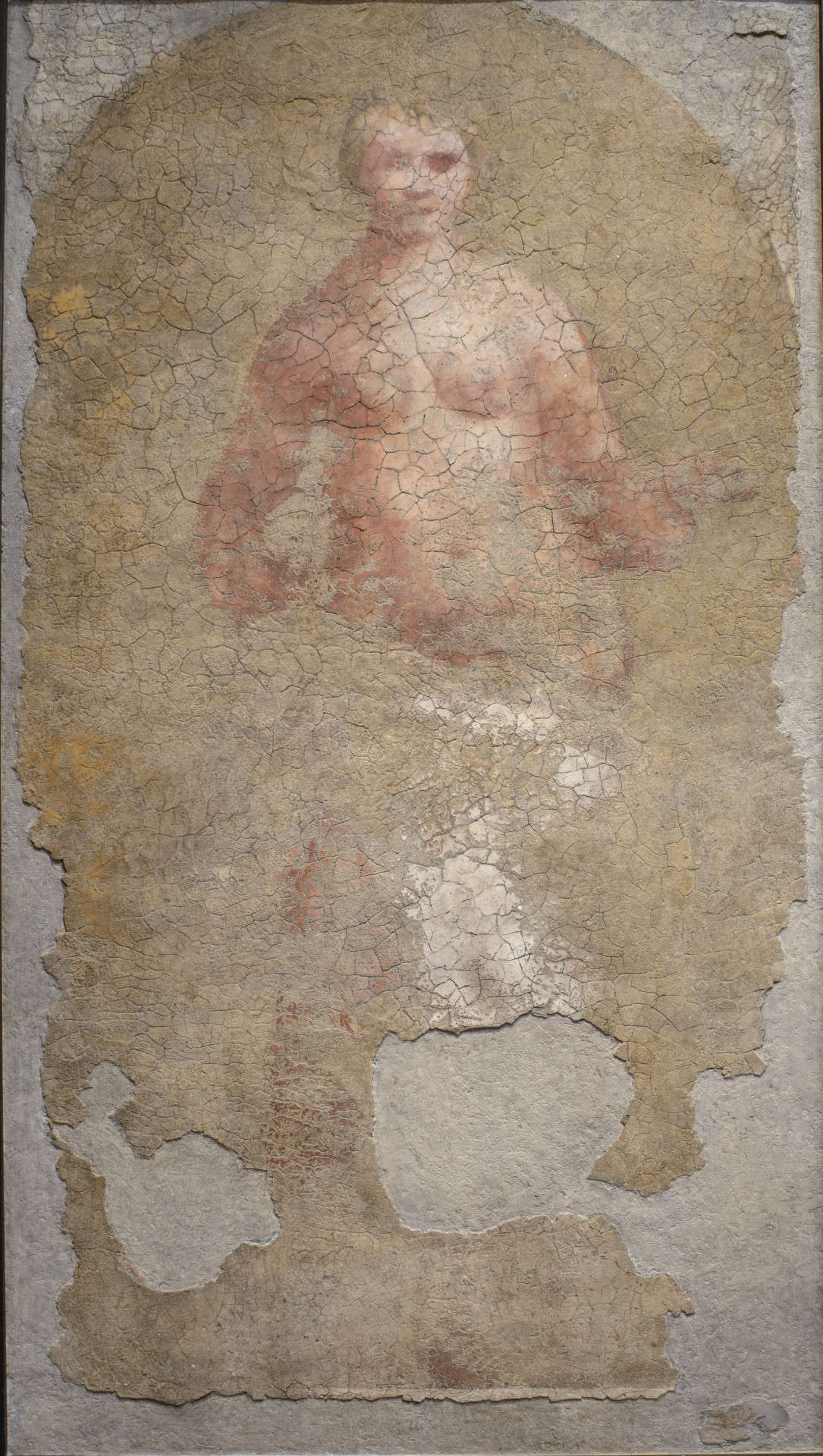

It is likely that the building was designed with the typical construction practices of German buildings in mind, and the idea of decorating the facade with frescoes may also respond to this need, although we do not know for sure (in Germany and neighboring areas, however, historiated facades were common). What we do know is that two great artists were involved in the reconstruction factory and called upon to embellish the facade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi. The Republic commissioned two of the greatest artists of the time, Giorgione and Titian, to fresco the building’s exterior walls with allegorical and mythological scenes. The iconographic program of the frescoes, if of course they were executed according to a precise program, is unclear, but it must not have been clear to many even at the time, since Giorgio Vasari himself would admit that he never understood what they meant. Our task today is made even more difficult by the fact that there are no known documents and that the frescoes have come down to us in only a few fragments: in fact, they were already in very poor condition in the eighteenth century, as attested by the works of the Vedutists in which the exterior walls of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi can be seen. The surviving images were all removed in 1937, when major restoration work began on the fondaco: to get an idea of what the facade must have looked like originally, we might think of the facade of Casa Parma Lavezzola in Verona. Here, too, the paintings on the facade are now a shadow of what they were, but they are still sufficient to give an idea of what it must have looked like in ancient times.

The frescoes in the Fondaco dei Tedeschi were painted around 1508: by Giorgione only the so-called Nuda remains, often interpreted as an allegory of peace, while by Titian the best-known surviving image is that of Judith or Justice, but the Companion of the Sock, an unspecified Allegory, a Combat of Giants and Monsters , and a Combat of a Putto with a Dragon also remain. According to scholar Alessandro Nova, Vasari would not have understood the meaning of the frescoes as: "surprised and sidetracked by an iconographic structure foreign to his own forma mentis. Where the culture of central Italy favored a closed and congealed structure of the concept, it responded in the north with a greater flexibility of themes not, however, without their own thematic coherence.“ It is therefore likely that the theme was not unique. Nova thought of a cycle by Giorgione, the one on the facade facing the Grand Canal, addressed to the stockbrokers and bankers who worked on the opposite bank and therefore every day had the facade of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi under their eyes: a cycle that blended astronomical and allegorical elements, probably related to trade, money and precious metals, a ”series of personifications of the planets,“ Nova wrote, ”under the protection of the peaceful lion of Mark," which stood on the two turrets at the corners of the fondaco, later demolished in the 19th century. Of political character, on the other hand, might have been Titian’s cycle on the Mercerie side: political significance, moreover, must have been the Judith, perhaps a symbol of Venice’s defense against some aggressor. Some have also wanted to read in the Titian cycle a possible allegory of the friendship between Venice and the empire. A friendship, however, that was destined to be very short-lived, since precisely in 1508 the Third Italian War, also known as the War of the League of Cambrai, broke out, promoted by Pope Julius II precisely against Venice, at that time the most powerful state on the Italian peninsula. The pope had allied with France, the Empire, the Kingdom of Aragon, and many states antagonistic to the Venetians, Ferrara, Urbino, and Mantua being the most important. The context was extremely fluid and alliances changed several times (even, for a few years, due to strong disagreements between Julius II and his French ally, the League of Cambrai was dissolved and the pope, in order to counter the overpowering former ally, even allied himself with his enemies the Venetians), but the Venetians, who eventually won the war together with the French in 1516 (in fact, in the last three years they were lined up on the same front) would always be pitted against that Holy Roman Empire from which the German merchants came.

The Fondaco was a fundamental place of work for German merchants, although the term “Germans” in the contemporary sense is restrictive: we have to imagine that merchants from all areas north of the Alps worked here. These lived in a kind of microcosm governed by precise laws. The merchants who resided here (there were in fact also lodgings) paid rent, and the same was true for businesses that had chosen the fondaco as their headquarters or to open an office there. These were mostly temporary stays related to the needs of commerce; there were few who resided here permanently. Day-to-day activities were monitored by officials of the Republic, who ensured the transparency of operations and the security of trade, also taking into account the fact that income from trade was crucial for the Republic.

All kinds of goods were traded here: textiles (mainly wool and cotton), metals from the vast mines of northern Europe, and typical northern European products such as furs and leather. However, the Fondaco was not only a place where Venetians imported German goods: the opposite also happened, with German merchants buying goods on the Venetian market and bringing them to their lands. The goods that took the route to the empire were mainly spices from the East, textiles, alum, luxury goods, and works of art.

Daily contact between German and Venetian merchants generated a lively cultural exchange. Germanic merchants brought with them not only goods, but also ideas, technical knowledge and innovations that enriched the lagoon city.

With the decline of Venice’s commercial power beginning in the 17th century, the role of the Fondaco also changed. Its original function as a warehouse for German merchants gradually declined. After the end of the Serenissima in 1797, the Fondaco lost its function and was used as a customs house by the French occupiers. Later, in the years of Austrian occupation, this administrative function was not changed, and indeed the Austrians implanted the Intendenza di Finanza and the Ispettorato del Demanio in the fondaco. Even after 1870, the year in which the Veneto became part of the Kingdom of Italy, the Fondaco retained its administrative seat: it was given to the Post Office, was for a long time home to post offices, and between 1937 and 1938 underwent a radical restoration, during which, as anticipated, the surviving frescoes on the facades were detached. The building remained the property of the Post Office until 2008, when, for the sum of 53 million euros, it was purchased by the Benetton group.

TheBenetton group undertook an ambitious restoration project, entrusted to renowned architect Rem Koolhaas and his OMA studio. The goal was to transform the building into a multipurpose center: a luxury venue that would house stores, cultural spaces, and a rooftop terrace, thus reflecting, to some extent, theancient vocation of the place. OMA’s renovation project had set out to create a sequence of public spaces and pathways by imagining each intervention “as an excavation through the existing mass, releasing new perspectives and revealing to visitors the true substance of the building, as an accumulation of authenticity,” wrote Rem Koolhaas. “The project, composed of both architecture and programming, opens the courtyard plaza to pedestrians, maintaining its historic role as a covered urban ’field.’ The new roof is created by the renovation of the existing 19th-century pavilion, which stands on a new steel and glass floor that hovers above the central courtyard, and the addition of a large wooden terrace with spectacular views of the city. The roof, together with the courtyard below, will become a public place, open to the city and accessible at all times.”

New entrances to the building from Campo San Bartolomeo and Rialto were created, existing entrances in the courtyard, used by Venetians as a shortcut, escalators were added to create a new public path through the building, rooms were consolidated to respect the original sequences, and some crucial historical elements such as the corner rooms remained intact.

The restoration was completed in 2016, and the spaces leased to the company Dfs , which established an upscale mall there that not infrequently hosted contemporary art exhibitions, with the idea of evoking the artworks that once adorned the building’s exterior as well as interior. Then, in November 2024, news broke that the mall would be closed in 2025.

The Fondaco dei Tedeschi is thus a place that combines past and present. While its modern interiors house stores and cultural spaces, the Renaissance structure and rooftop terrace are reminiscent of the grandeur of Venice’s past. It is an example of how historic monuments can reinvent themselves while keeping their heritage alive. The Fondaco dei Tedeschi embodies the spirit of Venice: a city that, over the centuries, has been able to continually reinvent itself while remaining true to its nature as a crossroads of cultures. Its vicissitudes, from its medieval founding to its contemporary rebirth, tell not only the history of La Serenissima, but also that of Europe and the world, in an interweaving of trade, art and human relations that continues to inspire.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.