The female body according to Albrecht Dürer

The Museum of the Battle and Anghiari holds an important nucleus of graphic works by Albrecht Dürer (Nuremberg, 1471 - 1528), a great artist considered the greatest exponent of the German Renaissance who was able to bring theart of engraving to high levels for the first time, thanks to his great technical skills, but above all for having made engraving an accomplished artistic language in its own right, going beyond the sole function of circulating certain compositions and images. Indeed, in his treatise Malerei und Zeichnung published in 1891, Max Klinger, about Dürer’s graphic work stated that “it does not arouse in us the idea of the transposition of a pictorial image, it does not seem to want to translate chromatic impressions as such, nor is it left with a feeling of incompleteness: it is in itself accomplished, and what it shows was intended just so, regardless of what the eternal impossibility of fully implementing one’s intention takes away from any artist. [...] It was possible for him to grasp the form, the action, the state of mind: the colors of which he could have made use would have led his imagination back into the real world, and instead he transcended this world.”

The important nucleus was donated to the Museum in 2021 thanks to the generosity of collector Giorgio Bagnobianchi and his desire to share his collections of prints, maps, paintings, and books to make them visible to all through an institution that could enhance them with exhibitions and educational activities. Although not an Anghiarian, but a lover of the Tuscan village since the first time he visited it to admire the works of Piero della Francesca preserved in the area, above all the Madonna del Parto, Bagnobianchi found in the Municipality of Anghiari the possibility of realizing this dream of his of public sharing. A gift he made to the town of Anghiari from the heart.

Indeed, precious engravings by Dürer are part of the Bagnobianchi Fund, and some of them can be seen for the first time now on display at the Museum of the Battle and Anghiari until March 8, 2023, as part of the exhibition Stories of Women. From Albrecht Dürer to the Contemporary by Ilario Fioravanti, curated by art historians Benedetta Spadaccini (aggregate doctorate and assistant curator Drawings and Prints at the Veneranda Biblioteca Ambrosiana) and Gabriele Mazzi (director of the Museo della Battaglia e di Anghiari) and produced by the city together with the Museo della Battaglia e di Anghiari.

Among the graphic works on display, two burin engra vings depicting Adam and Eve and The Sea Monster, respectively, both executed after the artist’s first trip to Italy between 1494 and 1495, deserve a closer look, as they are of considerable importance from both a compositional and technical point of view. For the great Nuremberg artist, in fact, his encounter with the Italian Renaissance, from which he sought to assimilate grace and proportion in the representation of the human body in pursuit of ideal beauty, was crucial, as was his meeting with Jacopo de’ Barbari in Nuremberg between 1501 and 1502, who moved from Venice to Germany. In German culture, nude bodies appeared artificial and unnatural; there was a certain resistance to accepting classical nudity, and Dürer was well aware of this. But it was through the encounter between the German tradition and the Italian Renaissance that Dürer was able to depict proportionate and natural nudes: he was the first northern artist to depict nude bodies according to these harmonious principles.

With theAdam and Eve of 1504 Dürer presents two ideal bodies perfect in pose and proportion, but also modeled with classical convenience, going beyond the Vitruvian calculations by which nudes were “constructed,” as in the Nemesis of 1501.

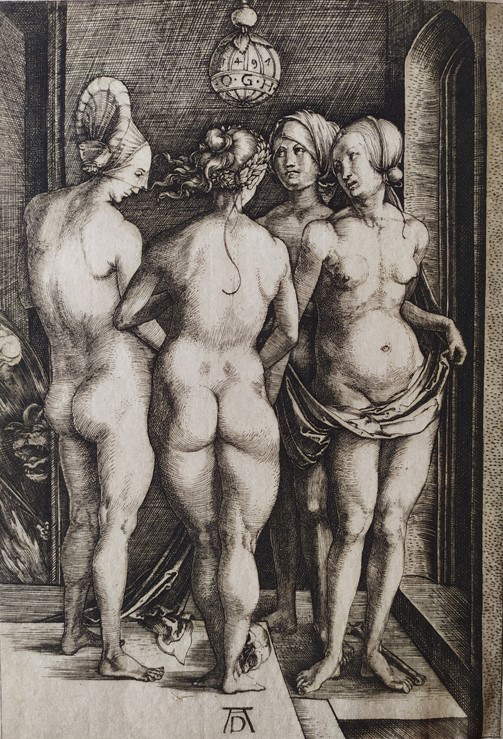

The nude had already been addressed by him as a subject in the first burin on which he had affixed the date, namely the Four Nude Women, dated 1497. These are four nude female figures depicted standing in an interior setting, arranged in a circle so that they can be shown frontally and from the back, echoing the iconography of the Three Graces with the addition of a fourth figure in the background. A kind of study of the female figure caught from several points of view, although Erwin Panofsky also detected in this work an allegorical-didactic meaning: “an extraordinary display of female nudity, understood as modern in the sense of the Italian Renaissance [...], turned into an admonition against sin.”

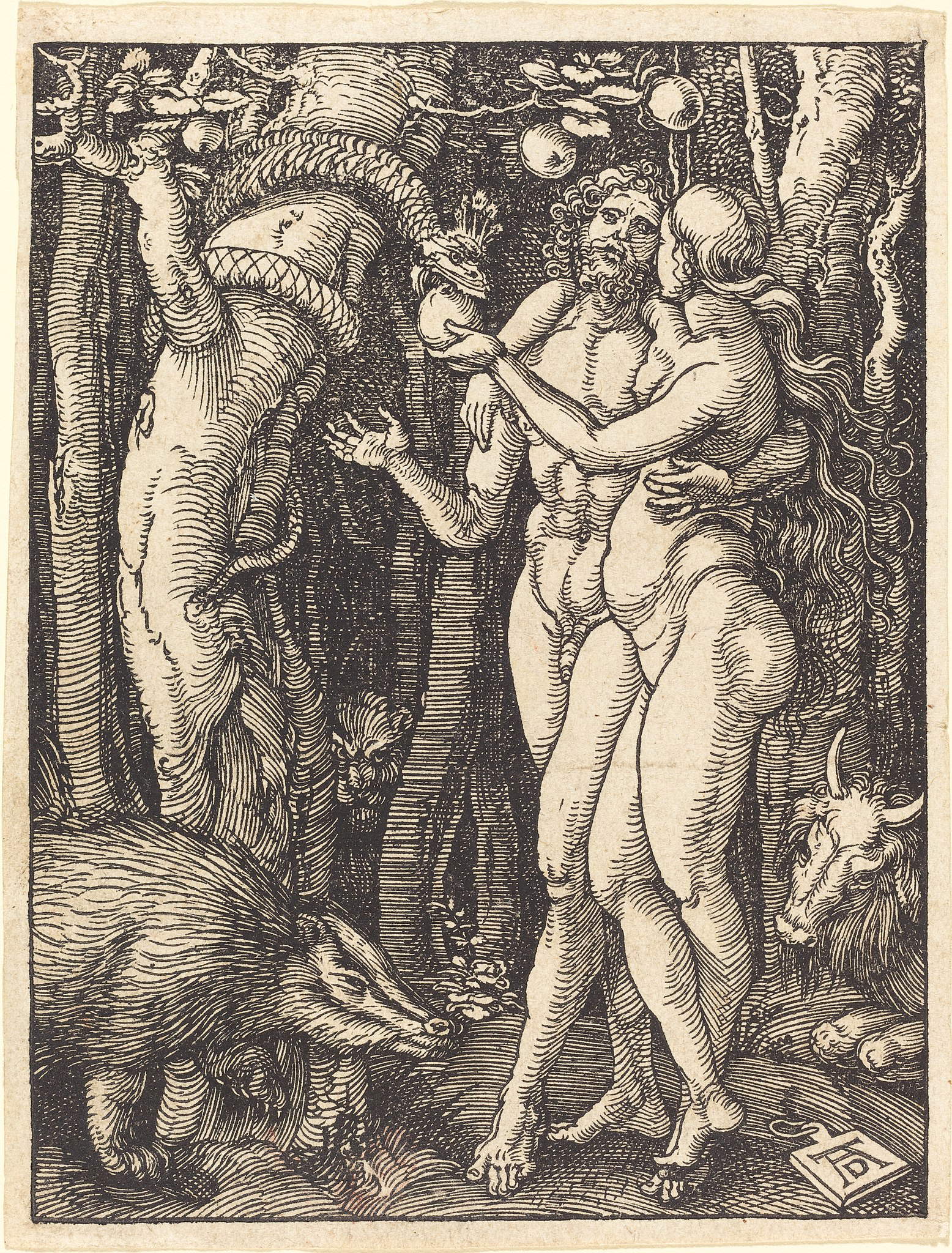

In theAdam and Eve we reach the full realization of the perfect model of the human body, both technically and aesthetically. Adam and Eve are represented here among trees, naked, covered only in their sexes by leaves. They are immersed in a natural environment rich in symbols, connecting the theme of Original Sin to the theory of the four temperaments, which are represented by the animals the artist has introduced into the work. The luminous two bodies of Adam and Eve, still uncorrupted, are counterpointed by theshadowy wooded atmosphere in which the animals are found (the different temperaments have in fact not yet entered the two bodies because they have not yet eaten the fruit of sin, namely the apple, which Eve is taking from the serpent’s mouth; the corrupted body will accommodate them, determining which one prevails over the others): the cat symbolizes bilious cruelty against the mouse, of themoose melancholy, the rabbit sanguine sensuality, and the ox phlegmatic apathy. Two other animals also are allegorical references: the chamois placed on the rock in the upper right background symbolizes the eye of God who sees everything from above, and the parrot, resting on the branch of theTree of Life grasped by Adam, symbolizes the praise raised to the Creator. The presence of animals together with Adam and Eve is also found in the Original Sin panel of the Lesser Passion cycle completed between 1508 and 1512, but unlike the earlier work Adam and Eve are clasped in an embrace and different animals represent the four temperaments: the lion symbolizes the choleric one, the bison the melancholic one, the badger the phlegmatic one, and the pair of Adam and Eve the sanguine one.

The 1504burin engraving , which for the artist constitutes the achievement of the masterful use of this technique, which consists of engraving the drawing in a metal plate, is signed and dated in full in the sign hanging from the Tree of Life: “ALBERTUS | DURER | NORICUS | FACIEBAT | 1504”; signature and date are accompanied by the monogram AD. It was preceded by many preparatory drawings, the most famous of which is the pen drawing preserved at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York, while the double painting of Adam and Eve preserved at the Prado Museum dates from three years later, 1507.

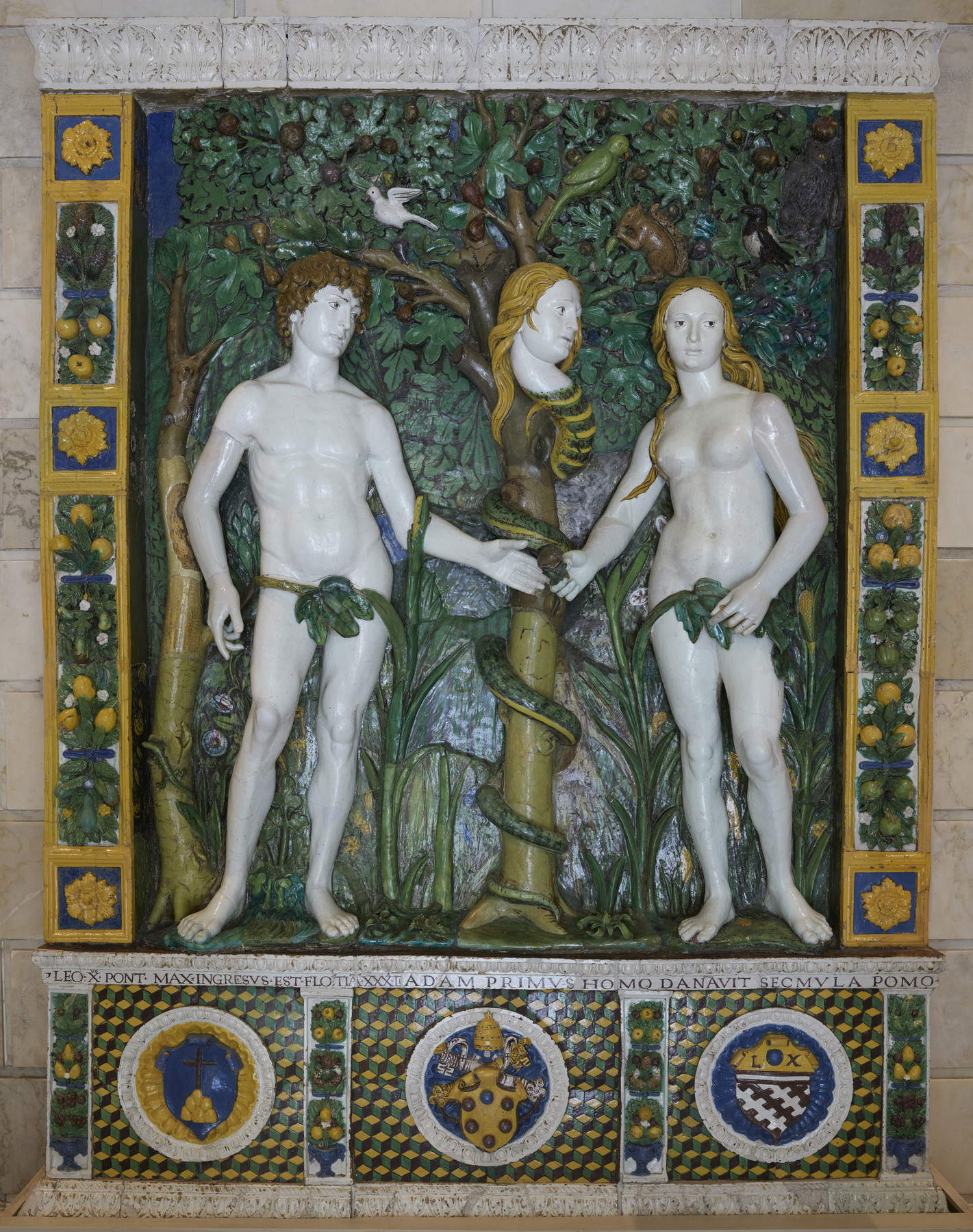

However, the composition of the engraving was so successful that individual parts were taken up in 16th-century Italian engravings and in various paintings and sculptures: examples include Dosso Dossi’s Circe, now in the National Gallery in Washington, and Giovanni della Robbia ’s glazed terracotta with the Temptation of Adam in the Walters Art Gallery in Baltimore.

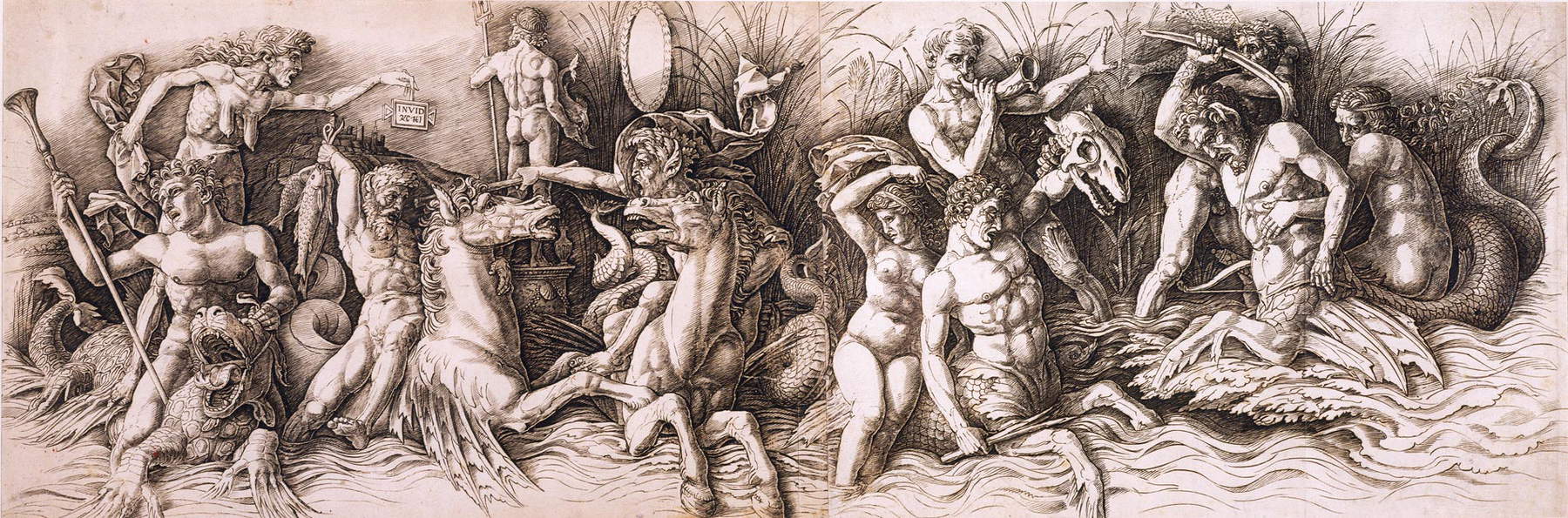

Preceding theAdam and Eve is a burin engraving entitled The Sea Monster by Dürer himself. Created in 1498, the work again depicts a nude figure, a maiden, who, while bathing in the waters amid rippling waves, is abducted by an older half-man, half-fish creature that carries in one hand a sort of carapace-looking shield. The backdrop is a village at the base of the mountain, on the top of which instead stands a castle reminiscent of that of Nuremberg. On the shore a man is running and despairing over the abduction of the maiden, and some bathers from the water observe what has happened.

Signed in the lower center with monogram AD, the engraving is named Das Meerwunder by its author, but the source of inspiration for this work still remains obscure . Indeed, it remains one of Dürer’s most enigmatic prints: it stands out for its curious subject matter that is difficult to decipher. This is why it is considered a"conversation piece," in that ambiguities are an integral part of the work and lead a selected, educated and humanistically trained audience to a true conversatio, an exercise in reading and commenting on the work to share with others. That this is a kidnapping and not an escape is understood precisely from the male figure in oriental robes who stirs on the shore, perhaps the father or lover of the kidnapped woman, but especially from the female figures still in the water who make their distress manifest. The woman was certainly one of them, although the elaborate and luxurious headdress with pearls indicates a different status from the others; she turns her gaze toward them as she is carried away by the sea creature, for whom she feels no interest.

Except for the headdress she wears on her head, the figure is completely nude, but in this case she is lying down, unlike the nudes that have been mentioned so far and the Four Nude Women that the artist depicted in 1497. This could therefore be seen as a study of a reclining nude. The maiden bears a striking resemblance, however, to the Nude preserved in theAlbertina in Vienna, a drawing by Dürer from a few years later, in 1501: it seems that the latter is based on a woodcut found in the Hypnerotomachia Poliphili, a novel published in Venice in 1499 of which the artist later acquired a copy.

In The Sea Monster,formal classical inspiration is evident, ranging from ancient art to Andrea M antegna (in particular Mantegna’s The Struggle of the Tritons copied by Dürer in 1494) and the theme of the abduction of a maiden, recurring in Greco-Roman mythology. Even Vasari in the Giuntina edition mentions “a nymph carried off by a sea monster, while some other nymphs bathe” carved in a “major copper.” Although critics have tried in the past to look for amythological allusion, none of the proposed subjects have fully convinced: among the hypotheses put forward are the rape of Anemone, Perimele and Acheloo, Anna Perenna and Numicius, and Glaucus and Sime.

Erwin Panofsky cites Poggio Bracciolini who relates a tale in which the story of a triton is transferred to the 15th century and the coast of Dalmatia: a half-man, half-fish monster with small horns and a flowing beard, who had a habit of kidnapping children and girls frolicking on the beach, until he was killed by five washerwomen. Fedja Anzelewsky suggested the reference to the ancient German story of the Longobard queen Theodolinda being kidnapped by a sea monster. In 1472 the story in 31 stanzas had appeared under the title Das Meerwunder within a cycle of German legends compiled by the nobleman Kaspar von der Rhön in Nuremberg. In 1552 the same story became a prose narrative thanks to Hans Sachs.

TheAdam and Eve and The Sea Monster are considered to be two of Albrecht Dürer’s most important graphic masterpieces, and the exhibition at the Museum of the Battle and Anghiari gives the opportunity to admire them here for the first time thanks to the generous collector’s gift, who was in love with the village.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.