by Federico Giannini, Ilaria Baratta , published on 06/08/2019

Categories: Works and artists

/ Disclaimer

To protect themselves from "fascinus," or the evil eye, the ancient Romans used curious phallic-shaped amulets: many can be found in many archaeological museums around the world.

The “fascinus” of ancient Rome: the phallus-shaped amulet that protected against the evil eye

Anyone who has visited an archaeological museum with a section devoted toRoman art will have come across phallus-shaped objects at least once: they could have been amulets, oil lamps, tintinnabula (a sort of Roman version of the scacciapensieri that hangs on the front doors of a house or store) or other everyday objects, but themale organ is often a major protagonist of ancient Roman artifacts. To understand why this constant presence is necessary a premise to introduce the topic of superstition among the ancient Romans: and that with superstition was a constant and daily relationship for the Romans, since even the smallest mishaps of everyday life involved gestures or rituals to ward off any worsening, while more serious situations (such as illnesses or accidents of all kinds) involved the intervention of real magicians, specialists in formulating spells (which, according to the beliefs of the time, had to be conducted with precision, otherwise they would be ineffective), called upon to gain the favor of the deities. In ancient Rome, the line between superstition and religion was very blurred: gods and demigods of the official religion, wrote scholar Maria Grazia Maioli, “had specific characteristics and attributes, rigid formulas required for invocations and prayers, favorite animals to be offered and sacrificed; the precise observance of ritual leads to the security of the result, both when the sphere is that of the higher religion, of relations with the heavenly and underworld gods, and when it is something much lower, but very important in everyday life, such as healing, for example, from a cold or an upset stomach; the Roman family religion knows infinite deities, whose function is to protect every moment of life [....]; to have their support it was enough to make a small offering, such as a pinch of flour, or to make a precise ritual or superstitious gesture, without which, however, everything would go wrong, an everyday religion, often unknown or barely mentioned in the sources, but which filled every moment, between practical superstition and petty magic.”

What was the cause attributed to the evils that struck the ancient Romans, especially those that happened suddenly? For the Romans, it could often be the results of an evil spell or anegative influence, also called in to explain illnesses whose causes were unknown at the time: one of the great bogeys of ancient Rome was the fascinus, the evil eye, an evil influence that was believed to be transmitted by words, by particular gestures or simply by a look. It was the so-called oculus malignus, “evil eye,” the exact ancient correspondence of the term “evil eye”: it was thought that there were people, endowed with deformed or enchanting eyes, capable of casting evil spells just by looking at a person. This power was sometimes also attributed to entire families, as we learn from reading the seventh book of Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis Historia, where the author writes that "in Africa there exist, according to Isigonus and Nymphodorus, families capable of casting fascinus and who with their praise are able to kill herds, dry up trees, and cause infants to die. Isigonus adds that people of this kind are also among the Tribals and Illyrians, and they are able to cast fascinus even with their eyes alone and are able to make those whom they stare at for a long time die, especially if they do so with angry eyes." We do not know for sure where the term fascinus comes from: there are those who have related it to the Greek báskanos (“slanderer,” “jinxer,” “beguiler”) and still those, on the other hand, who believe that it has to do with the Latin noun fascia (“sash,” as if to say that fascinus is a spell that ensnares and entraps those who receive it). And it is, moreover, from the term fascinus that the Italian “fascination” derives (think of the negative meaning the term can have, if understood as a spell capable of subjugating those who suffer it).

Fascinus could have many effects, even fatal ones (sudden deaths were also attributed to the evil eye, and in addition to explaining the onset of diseases, it was also called upon to motivate poor harvests, livestock deaths, and accidents to one’s home), and it could affect everyone, but one category particularly susceptible to negative influences was believed to be children (as was only natural, since the youngest are more prone to fall ill than adults): they were made to wear the bulla, an amulet which they wore throughout childhood and which was believed to ward off the evil eye (“on the neck of children,” wrote Varro in De lingua latina, “an amulet representing an obscene figure hangs against the evil eye”). More generally, there were many ways to escape or ward off the fascinus. From the aforementioned rituals, there were simpler practices, such as apotropaic, superstitious, and averting gestures (some very ancient gestures still survive today: think of the horns gesture), but particularly widespread was the distraction of the evil eye by means of amulets: the most widespread of these was the phallic-shaped amulet, believed to be a very powerful means of warding off fascinus (so much so that amulets in the shape of phalluses were known by the same term: that is, the amulet was also called fascinus). Perhaps the most powerful visual representation of the symbolism associated with the phallus is a second-century AD bas-relief found in Leptis Magna (in present-day Libya) that depicts a leggy male organ caught ejaculating over an oculus malignus to neutralize its malefic effects.

|

| Bas-relief with phallus ejaculating over the oculus malignus (2nd century AD; Leptis Magna) |

The phallus was directly linked to the cult of the god Priapus, the tutelary deity of fertility, represented as a man with an enormous penis: the representation of male genitalia, precisely because of their references to fertility and abundance (and thus to the generative force of nature and the ability to give life), was attributed great superstitious power, and wearing a fascinus was considered an effective way to ward off the evil eye. And it was not only necessary to wear it, but it was also necessary to wear it in plain sight, since displaying it, as mentioned, would distract the gaze of the charmers and thus ward off their evil influences. The simplest charms were those that simply reproduced male genitals: several are found in many archaeological museums, and they are modeled naturalistically, often provided with testicles and, of course, a suspension ring to pass the necklace through (these were, in fact, objects that were worn around the neck). Often the ring was placed horizontally in relation to the shaft of the penis, so that, when worn, the tip of the erect organ would be threateningly turned toward the person observing the contraption. It should be specified that the display of these objects in most cases had nothing untoward about it (and, it is worth pointing out, representations of phalluses were seen in homes, in stores, along the streets): simply for the fact that Priapus was believed to be a positive god, capable of fulfillment, dispensing pleasure and abundance.

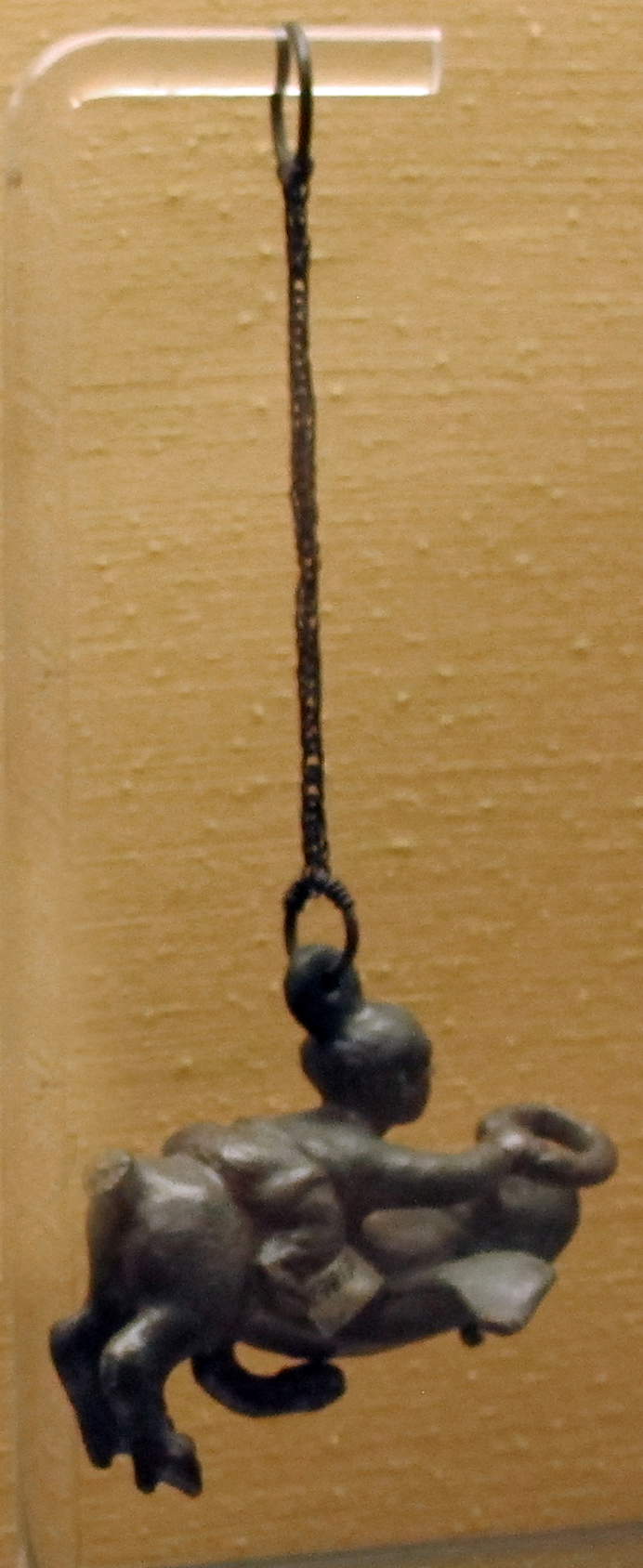

The imagination of Roman craftsmen was often inclined to take flight: objects featuring the winged ph allus or the phallus with legs stood out in the production of amulets, and the fact that male sex organs were represented with wings or legs symbolically alluded to the power of the phallus, its strength, its great vitality. In addition, scholar Carla Corti explains, in cases where it was depicted winged, the phallus “could also take on more obvious magical connotations”: in cases such as these, “the iconographic similarity with the figure of the winged horse was concretized, equipping the phallus with its hind legs and tail.” Another very typical and frequent amulet is the one depicting on one side the erect penis, and on the other a hand with a clenched fist making the so-called “pussy gesture” (i.e., passing the thumb between the index and middle fingers), which alludes to the female genitals and therefore in objects such as these had the function of uniting the dual generative force of the man’s organ and the woman’s.

|

| Roman Art, Phallic Amulet (1st-3rd century AD; copper alloy, 4.3 x 1.5 x 1.4 cm; Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard Art Museums) |

|

| Roman art, Phallic amulet (bronze; Trent, Castello del Buonconsiglio). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Roman art, Phallic am ulet (1st century AD; bronze; Venice, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Phallic amulet (1st-4th century AD; bronze; León, Museo de León) |

|

| Roman art, Phallic amulet with hand making the phallic gesture (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, Museo Archeologico Nazionale). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Roman art, Phallic amulet with hand making a scaramantic gesture (middle-late imperial age; bronze; Piacenza, Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese) |

|

| Roman art, Winged phallus with legs (1st-3rd century AD; bronze; Prague, Kinský Palace) |

|

| Roman art, Winged phallus (middle-late imperial age; bronze; Piacenza, Musei Civici di Palazzo Farnese) |

|

| Roman art, Winged phallus with legs (1st century AD; bronze; London, British Museum) © The Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| Roman art, Quadruped-bird phallus with phallic scorpion tail and two insects on its back (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum). Ph. Credit Marie-Lan Nguyen |

The compositions could also get much more complex. Phalluses could have lion’s paws and tails (so-called “lion phalluses”) and could even be ridden by the most varied figures (some interesting examples of this can be found at the National Archaeological Museum in Naples, inside the Secret Cabinet, which houses a vast collection of objects with erotic subjects). Sometimes, moreover, the phallus was ridden by a female figure: medievalist David Williams has written that this symbolism is the origin of the much better-known image of the witch riding a broomstick. In some cases the phallus became so animated that it attacked its...possessor, resulting in grotesque outcomes: again in Naples, for example, the figure of a warrior fighting against his penis, which took on the form of a panther, is preserved. Again, it sometimes happened that the fascinus with which to arm oneself against the evil eye depicted not simply a phallus, but an ityphallic deity (i.e., with an erect penis), typically Priapus, but also Mercury. The symbolism of the phallus since ancient times was also linked to the cult of Mercury: the association between the Greek and Roman god of commerce and phallic allegories derives from some cults in the Greek area within which the god Hermes (later to become the Mercury of the Romans) was identified with the god Kadmilos, worshipped in Samothrace in ancient times (he was a fertility god and was also depicted in an ityphallic attitude). Also preserved in Naples is a Mercury riding a ram (an animal related to the god, as well as to Kadmilos: it was also, for both, the beast that was preferably sacrificed to them during rituals), equipped with a phallus of enormous proportions.

Many of the figures mentioned above were placed in tintinnabula: these were objects that, as mentioned in the opening, were akin to the more famous “scacciapensieri.” That is, a tintinnabulum was a rattle, typically made of bronze, that was hung on the doors of houses and stores, usually consisting of a main figure and a series of bells that were hung on it, so that the wind or the opening of a door would make it ring. The sound of the tintinnabulum was thought to distract jinxers and thus ward off the evil eye-a power that grew if the object took phallic forms. Throughout the Roman empire there are many tintinnabula that have emerged from archaeological excavations and are now preserved in museums around the world.These were, in fact, objects of common use and of relatively wide dissemination (in other words, there were many Romans who had phallic amulets, but not all of them possessed them: after all, when one considers that much of the power of these amulets resided in their ability to surprise those who cast evil spells, they would have had no effect if the evil-doers were accustomed to seeing them). And the weirder and more bizarre the amulets were, the more powerful they were thought to be, since they were considered capable of distracting jinxers for longer.

|

| Roman art, Phallus-shaped Tintinnabulum with bells (1st-3rd century AD; bronze; Berlin, Staatliche Museen, Antikensammlung). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Roman art, Tintinnabulum with jockey riding and crowning a large phallus and about to be penetrated by the phallic tail (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Tintinnabulum in the form of a jockey riding and crowning a large winged phallus (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Tintinnabulum in the form of a gladiator intent on fighting with a dagger against his own phallus transformed into an aggressive panther (1st century BC; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum) |

|

| Roman art, Tintinnabulum with polyphallic Mercury (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

|

| Roman art, Tintinnabulum with Mercury riding an ityphallic ram (1st century AD; bronze; Naples, National Archaeological Museum). Ph. Credit Francesco Bini |

If the objects seen so far served for personal protection against fascinatio (i.e., the magical practice of fascinus throwers: the most famous image is perhaps from Catullus’ Carme VII, where the poet asks tam te basia multa basiare / vesano satis et super Catullo est; / quae nec pernumerare curiosi / possint nec mala fascinare lingua, that is, he asks his beloved for “so many kisses that malignants cannot count them nor evil tongues can cast the evil eye against you.”) it is necessary for the sake of completeness to point out first of all that this superstition also had a public character (the ithyphallic herms of Dionysus and Hermes that already in ancient Greece were placed at the edge of fields or in the roads leading to cities were intended to invoke the protection of the gods for vast communities), and secondly how there was no lack of public rituals intended to escape the evil eye and ingratiate oneself with Priapus, who remained, however, Maioli explains, "a familiar god, glorious symbol of cheerfulness and good fortune, defender of borders and rights, sarcastically fierce with those who opposed him or who violated his protection, as can be inferred from the Carmina Priapica preserved to us by the sources: it is natural, therefore, that his chief attribute should also be treated in the same spirit." For the Romans, in short, it was not strange to see phalluses represented just about everywhere.

Reference bibliography

- Adam Parker, Stuart McKie (eds.), Material approaches to Roman magic. Occult objects and supernatural substances, Oxbow Books, 2018

- Megan Cifarelli, Laura Gawlinski (eds.), What shall I say of clothes? Theoretical and methodological approaches to the study of dress in antiquity, American Institute of Archaeology, 2017

- Jacopo Ortalli, Diana Neri (eds.), Divine Images. Devotion and divinity in the daily life of the Romans, archaeological evidence from Emilia Romagna, exhibition catologue (Castelfranco Emilia, Museo Civico, from December 15, 2007 to February 17, 2008), All’Insegna del Giglio, 2017

- Carla Conti, Diana Neri, Pierangelo Pancaldi (eds.), Pagans and Christians. Forms and attestations of religiosity of the ancient world in central Emilia, Aspasia editions, 2001

- Eva Björklund, Lena Hejll, Luisa Franchi dell’Orto, Stefano De Caro, Eugenio La Rocca (eds.), Reflections of Rome. Roman Empire and Baltic Barbarians, exhibition catalog (Milan, AltriMusei a Porta Romana, March 1 to June 1, 1997), L’Erma di Bretschneider, 1997

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools.

We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can

find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.