The fascination of color to discover light and the supersensible. The painting of Maurizio Faleni

If you want to start finding a motif for your own artwork, look at a stain on the wall. This was the suggestion that Leonardo da Vinci, in his Treatise on Painting, gave to young artists: the example came to him from a friend of his, a certain Sandro Botticelli, to whom, the Vincentian assured, it was enough to throw “a sponge full of different colors” against a wall to see, in the imprint left by the sponge, “various inventions of what man wants to look for in that, that is, men’s heads, different animals, battles, rocks, seas, clouds and woods and other similar things.” This is similar to the approach that has guided and continues to guide the recent production of Maurizio Faleni, a Tuscan painter who for at least fifteen years has been intensely experimenting with color, presenting himself with one of the most constant, determined and conscious abstract researches that contemporary Italian art offers its public. Constant, because it is a research that has long known no distractions: it has gone through variations, novelties, changes of direction and returns, but it has never lost sight of its objective, it has never looked away from the profound exploration of color. The determination of Faleni’s work coincides with its strength, and it emerges evident in all its energy as soon as this artist begins to talk about his works, and one understands that his research is first and foremost a personal fact, it is the reason for a coherent artistic path that does not submit to the taste of a gallery owner or, worse, to the dominant taste. If his work will then be able to touch the chords of those who will observe his works, fine: but first of all it is a necessity of the artist, an urgency that comes to him from his frame of mind, from his unconscious, from his memories. Faleni’s work, one might say paraphrasing the title of a recent book by Roberto Floreani, is a form of resistance: “in the abstractionist,” we read there in the first pages, “it becomes [...] indispensable a personal claim of belonging, of sharing in the principles and aims inherent in Abstraction, an expressive sphere oriented to analysis, to inner research [...], devoted, by its intimate nature, to the highest index of freedom, placing itself, without reserve, in the presence of the viewer and his intimacy.” In the presence of the observer, but in the conviction that art should be directed toward an intellectual dimension, with the knowledge that the idea of a unique and universal audience is unfounded, if not even “negative,” as Peter Halley defined it.

And to realize Maurizio Faleni’s awareness, it is enough to enter his studio, in the very center of Livorno, in a nineteenth-century villa that once belonged to the Rodocanacchi family, now entirely occupied by artists’ studios, a melancholic bohemian lacer mien swallowed up by building speculation, a rare surviving fragment of that fruitful and passionate community that we imagine when we read the stories of the Macchiaioli or those of the Caffè Bardi, or those of the Gruppo Labronico, a singular atom of the artistic Livorno of yesteryear that still survives. Entering Maurizio Faleni’s studio is an experience: it seems to cross the threshold of an alchemist’s laboratory. On a table, a long expanse of jars filled with color, each with its own label: “Giallo Delta,” “Grigio Wolf,” “Verde Mozart,” “Rosso Rubens,” “Arancio Calabria.” These are some of the names Faleni has given to his mixtures, which he fine-tunes after days of intense work on the pigments, to find the right shades, in search of the density, intensity, and fluidity that best suit the idea the artist has in mind, and that go well with the thin slabs of opaque aluminum that for some time now have been the surfaces that welcome his colors. Also for a symbolic reason: aluminum, as is well known, is a material that can be endlessly recycled. And this is Faleni’s way of conveying to the public his idea of art, which is that it is eternal. As long as human beings exist in the world, there will also be art, because the need to express oneself through art will never cease.

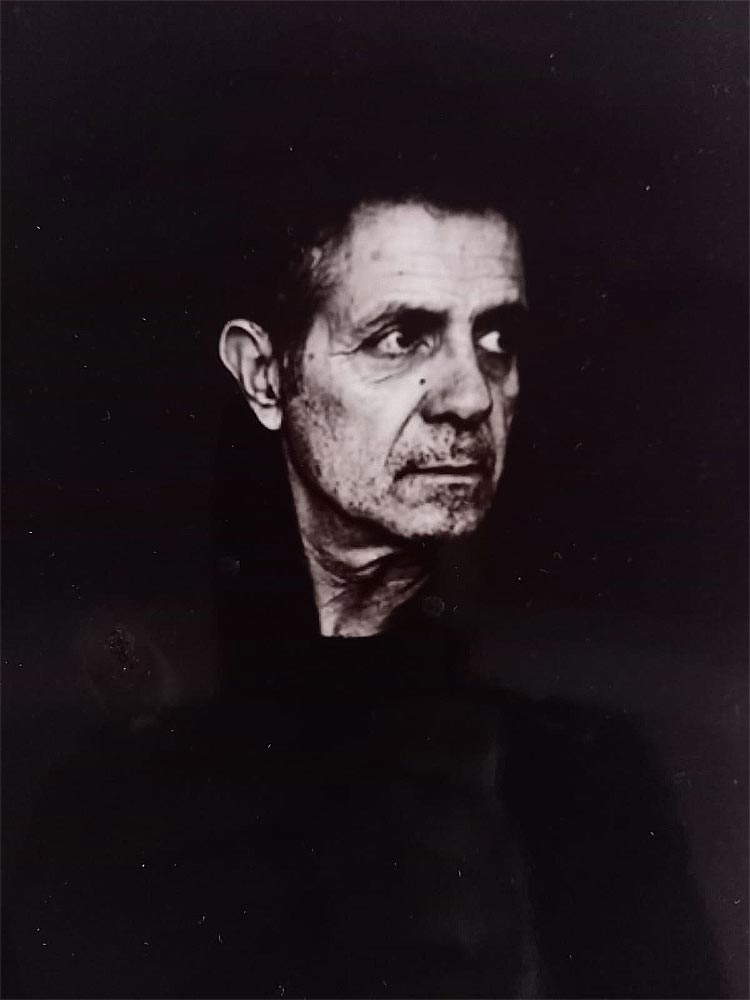

Maurizio Faleni,

Maurizio Faleni, Maurizio Faleni,

Maurizio Faleni, Maurizio Faleni,

Maurizio Faleni,Maurizio Faleni responds to this need through color. For him, color is everything or almost everything, it plays a prominent role in his work that unveils light by means of color, touches the areas of our brain that process abstract images, and comes to perceive, through color, beauty understood as “that dimension that composes the sensible with the supersensible” of which Umberto Galimberti speaks (“when you look at a painting and you are enchanted by that painting, what that picture represents does not only refer back to itself, but refers to an ulteriority of meaning.”). Touching the sensible to reach the supersensible, then: this, too, is one of the most concrete results of Faleni’s art. In this sense, the thunderbolt for color, he tells me, came from his encounter with Mark Rothko, deepened in 2007 when the Palazzo delle Esposizioni in Rome dedicated to him one of the most anticipated exhibitions of that season. What fascinated Faleni, however, more than the metaphysical intimacy of Rothko’s paintings, more than the almost spiritual lyricism of his paintings, was the sensitivity that the great abstract expressionist demonstrated for color. It is well known that Rothko had a rather ambiguous relationship with color, since on the one hand he aspired to maximum freedom, trying not to force his imagination to submit to constraints of any kind, and on the other hand he followed an extremely methodical approach when carrying out his experiments. Art historian Dore Ashton, in her book About Rothko which has become one of the main sources for studying the work of the American artist, wrote that “Rothko was always aware that his means were inferior to his vision because his means were material.” Faleni’s vision is less tragic than Rothko’s, since in Faleni human beings and nature seem to find some form of harmony, but the awareness behind his work is the same. The same, enveloping and profound seduction of light shines through his works: color is the medium by which Faleni tries to preserve a trace of it, recognizing that capturing it is impossible. The chromatic synthesis he seeks with his works is meant to be on the one hand pure and clear to express the potential of color, and on the other hand fluid and transparent to turn to light, to discover light. Some may therefore see similarities between the art of Maurizio Faleni and that of Claudio Olivieri. While these two artists seem to share a poetic and lyrical quality of color, they are nevertheless separated by a substantial difference: Olivieri always tended toward the infinite and sought to show the invisible, while Faleni’s art opens to a dimension that seems decidedly more immanent. And then, Faleni’s works of art are born from the encounter between chance and the freedom of the artist who decides to intervene with his gesture on that randomness, which, however, takes place within a scheme that the artist has created according to his own rules, while nevertheless being subject to the laws of nature and physics. Those who wish may also read in Faleni’s works a metaphor for existence itself.

One could then draw a parallel with the art of Paul Jenkins, another painter to whom it is possible to compare the art of the Leghorn artist, who is close to that of the Kansas City painter in terms of the attitude that is more typical of the phenomenalist than of the expressionist, for the attention to the natural datum (Faleni often draws inspiration from the colors he sees in nature: a rose garden exalted by the sun’s rays, he tells me, is for him one of the most powerful and abstract situations that one can have the privilege of admiring), for the gestural expressiveness that seeks to guide color without, however, harnessing or constraining it, for the intention to make manifest a condition of being, to bring out through color sensations that would otherwise be inexpressible. And this despite the fact that in Faleni’s path there have been “figurative” moments, as he calls them: now, however, his painting has taken a completely different direction. Faleni tries to avoid all the elements that can make his painting too descriptive. The public, then, will be able to see in his chromatic layering what everyone’s feelings will suggest: it is not uncommon that, at one of his exhibitions, someone approaches the artist to make him participate in what he sees in the painting. And this, too, is an achievement: because abstraction for Faleni is also a way of saying to anyone (with extraordinary concreteness, it comes to add, although it may seem paradoxical when thinking about his works), the same thing Leonardo da Vinci said, namely that all painting starts from a stain.

Perhaps it goes without saying to emphasize that, to arrive at the Livorno artist’s results, a very strong discipline is required, and solid practical knowledge, as well as knowledge of color theory and art history, is essential. Faleni’s “stains” traverse centuries of art backwards: they go through the whole affair of the Macchiaioli, go up the sinuous and animated lines of the Baroque, and arrive at Rosso Fiorentino, another painter watched with supreme interest by Faleni for the squillant and hallucinatory quality of his colors, and then back to Masaccio, to Beato Angelico, to Giotto. “Masters of color,” one might say, borrowing the title of a well-known editorial initiative of the past, and such they evidently are for Maurizio Faleni, because color intrigues him far more than the fact narrated, or the composition, elements that he always sees as strongly subordinated to accidental circumstances, be they the era or, more banally, the request of a client. Faleni aspires to the highest degree of mental freedom, which finds expression in the process by which he executes his paintings, and is substantiated in his colorful visions. The starting point, after the preparatory studies that Faleni performs on paper to find the best combinations and to try to see how the color responds by changing state, is always a point on the metal surface that is freely chosen by the artist, then the color is spread with the correct dosages to obtain the gradations he has in mind. Here then is the competition of chance: the color expands autonomously going to cover the surface the moment the artist decides that his intervention is finished, reserving, however, the right to intervene himself with a gesture to control the movement, if only to affirm his need to try to have his say in the face of randomness. When everything is stationary, the color is left to dry, again with due care, since the timing is different (the visible part dries first, but the part in contact with the surface can remain in motion for many days). One last step in the body shop to apply the final paint with industrial products (and thus give the monochrome paintings the shiny and reflective appearance with which they present themselves to the eyes of the relative), and the work can be said to be finished.

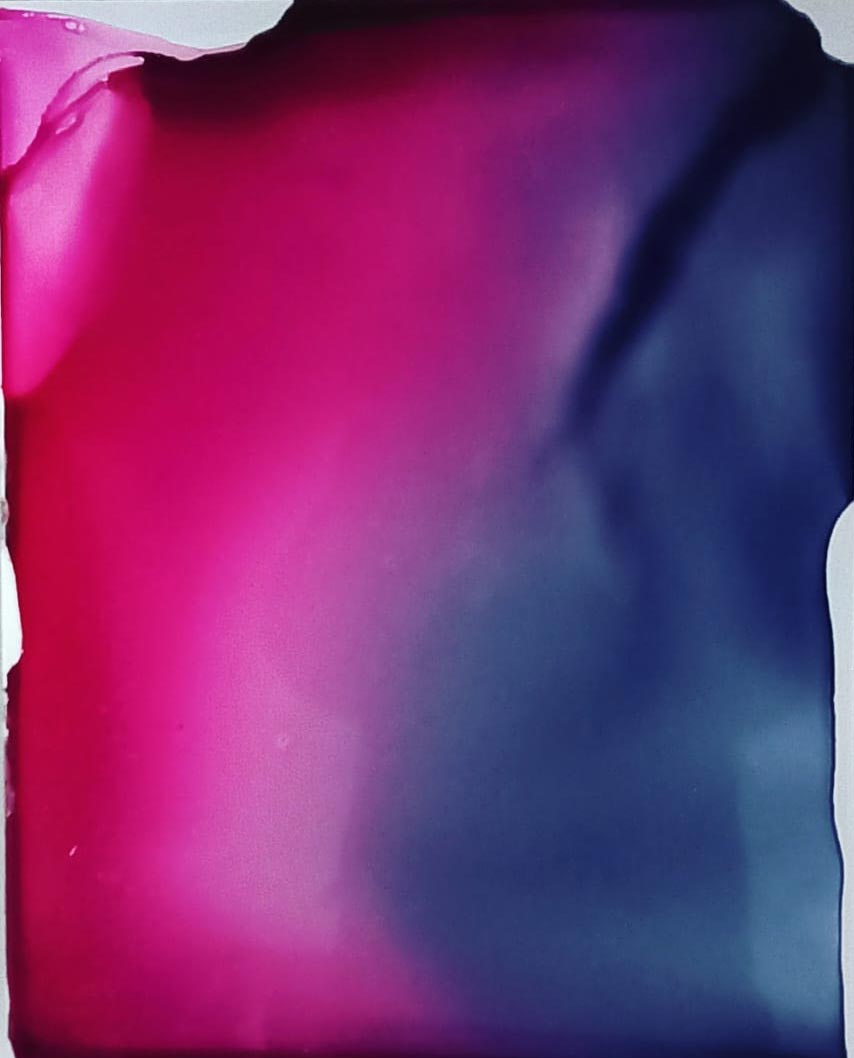

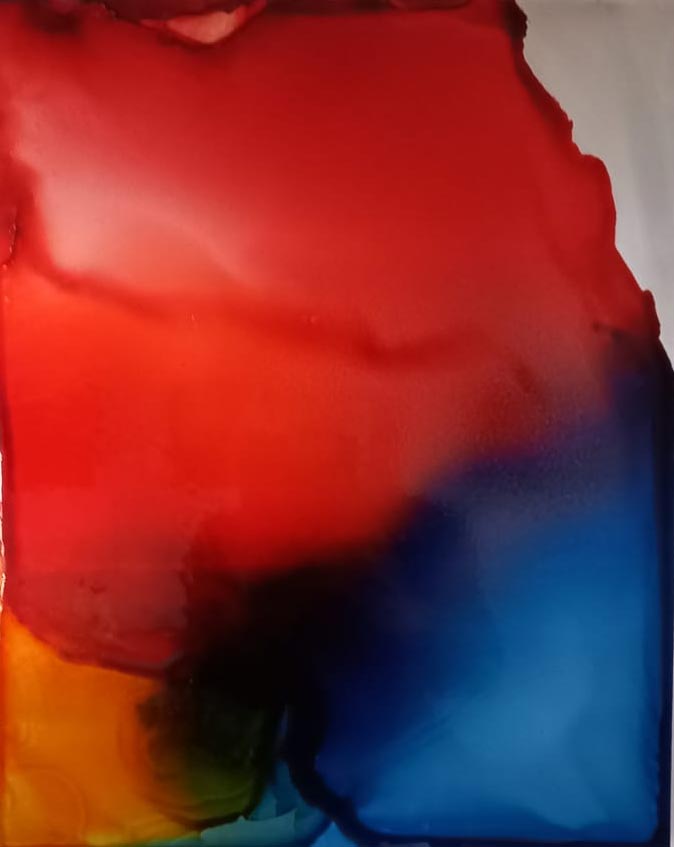

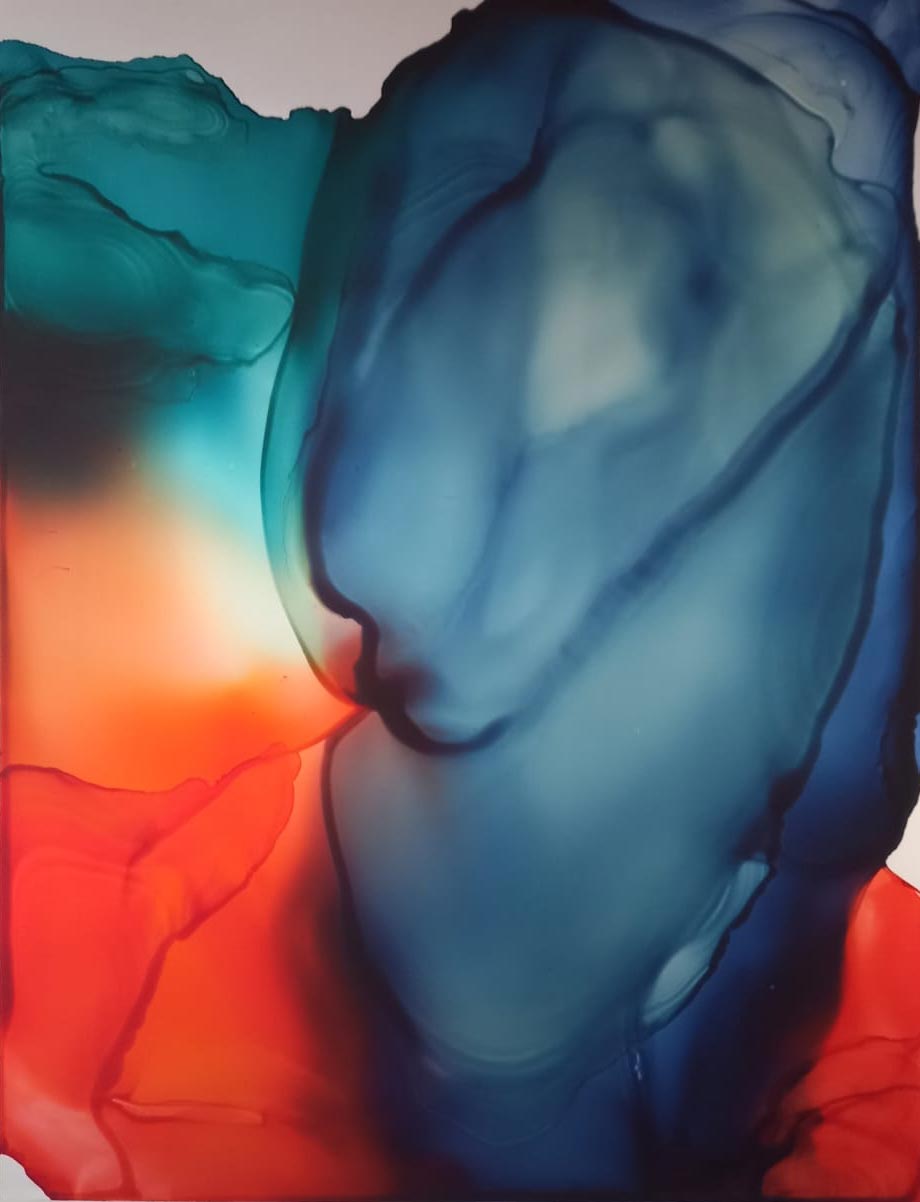

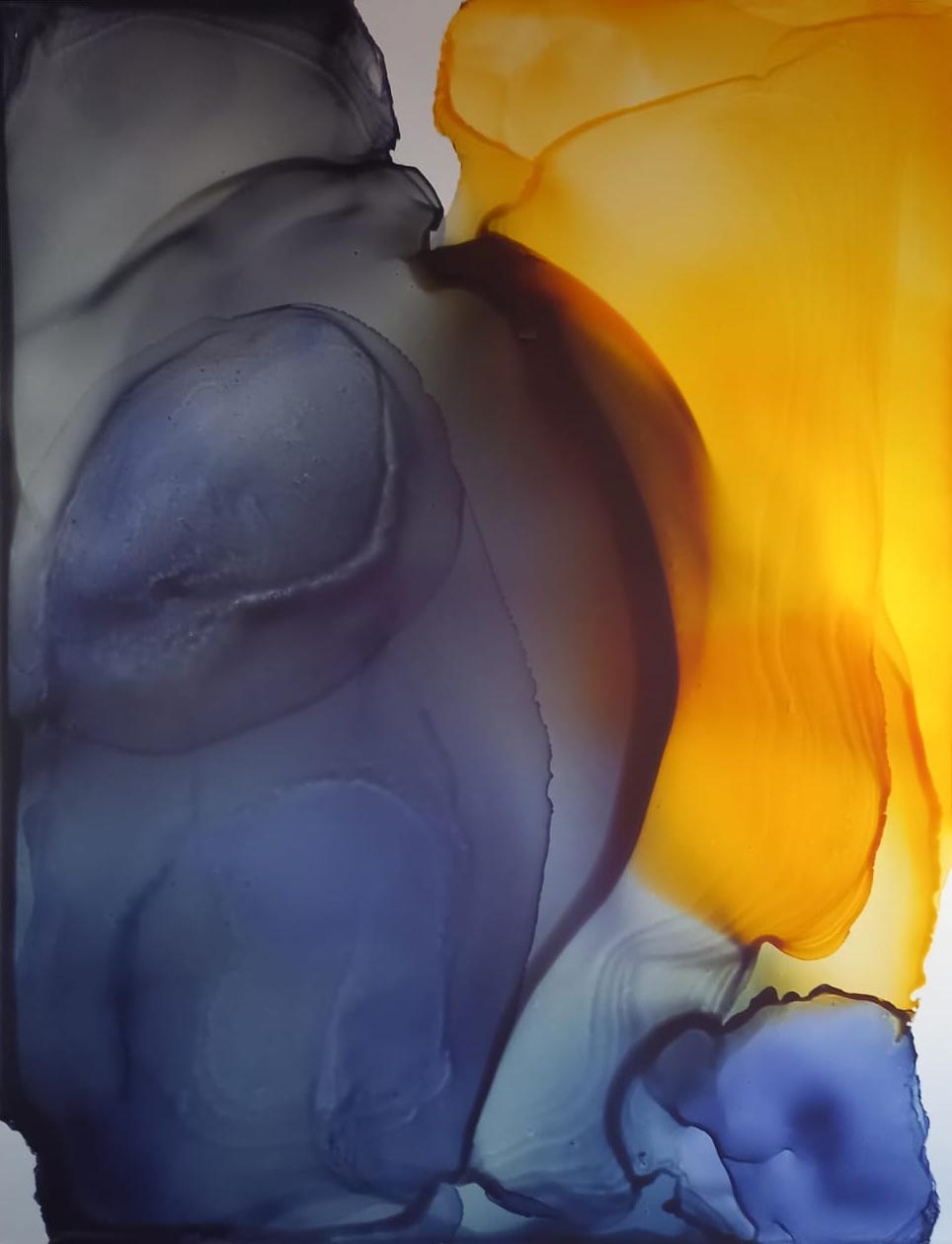

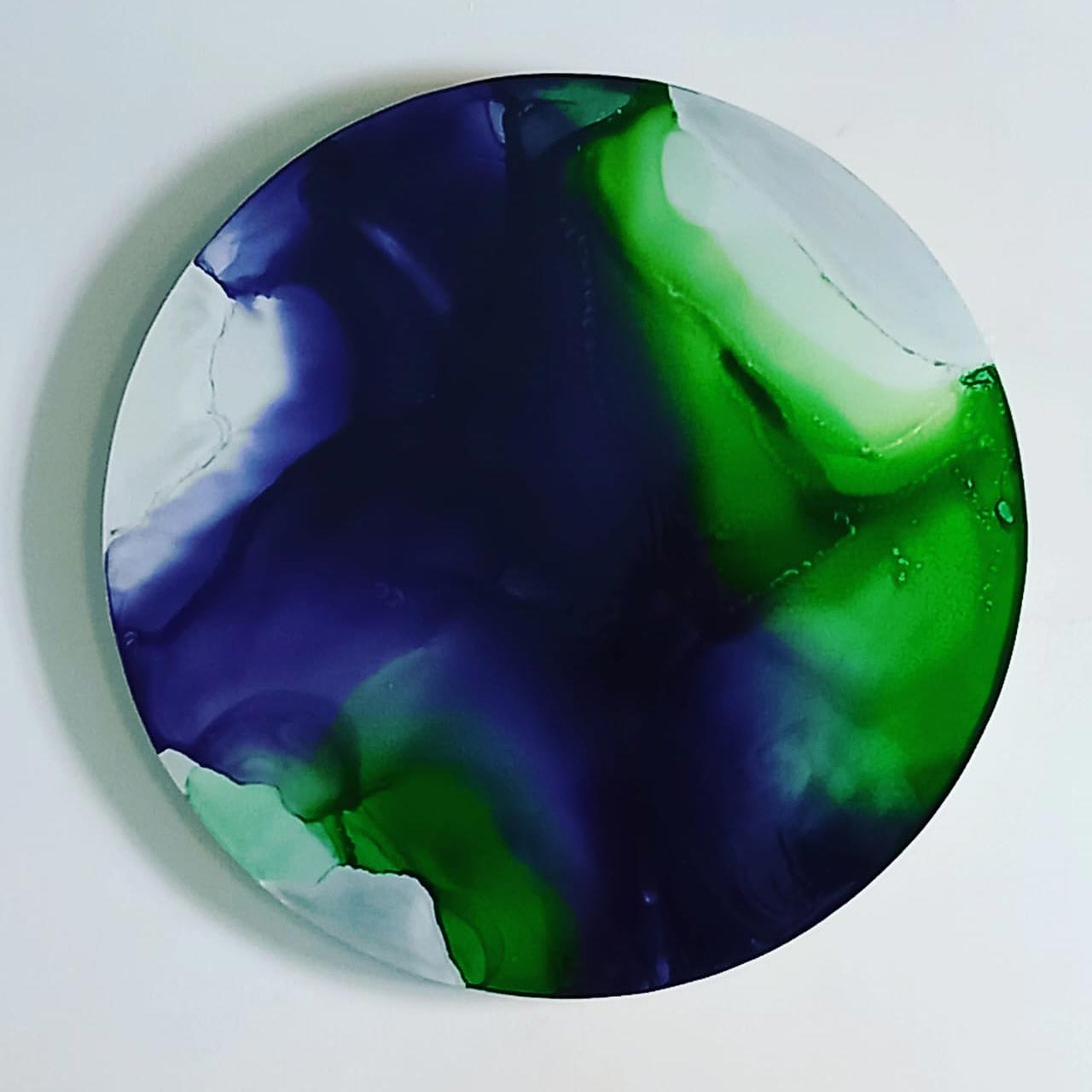

Recently, during the confinements to which we have been forced while the Covid pandemic raged in the world, Maurizio Faleni felt the need to take an alternative path and go beyond what he calls his “monochromatic phase,” to embark on a perhaps even more complex path involving the use and combination of different colors. The result is a series of bichromatic and polychromatic paintings to which the artist has given the title Osmosis, probably to make clear the sense of a transition, of a mutual integration, of a fusion between different tones, of an interpenetration. Interviewed by Gabriele Landi on Parola d’artista, this is how Maurizio Faleni defined his “osmosis”: “A process of exchange, of continuous flow between separate solutions, the starting point for the realization of a new way. Colors that meet and give birth to new colors, new emotions. The observer cannot control the uncontrollable, he only has to let himself go within the color dynamics and have a new experience. A seemingly abstract painting, a painting that turns into figurative vision or vice versa. Perhaps a new painting.” The impulse that moved Faleni toward these new investigations came almost suddenly, unexpectedly. “All my work,” he explains, “requires maximum concentration. During the operational phase the brain works incessantly until I decide to stop. Psychophysical energies are zeroed out. Neurons have maximally expressed synapses. My eyes burn. Muscles are stressed by forced postures. It is at night that, with restful sleep, my unconscious gives birth to new ideas, new challenges. All barriers break down and that is how a new path to take begins. So I set myself with reason and conviction and begin the new phase.” Thus were born, from an almost sudden and unthought-out idea, his most recent works. There are two or three colors that come together on the surface, which maintains the regular shapes on which Faleni has always worked: lately he seems to have developed a penchant for the round, the format on which he has most often worked is the rectangular, but in the past he has also experimented on the square, the triangle, and crosses. Faleni’s new works are chromatic harmonies, they are hypnotic dances, they are like symphonies of different colors that approach and recede, find and lose each other, play, merge, move freely on the aluminumopening up in transparencies and fades, sometimes thickening into denser clumps until they almost cancel each other out, sometimes becoming more rarefied until the surface is shown uncovered (which was not the case in the monochromes): the desire to show the aluminum stems not only from the desire to make it clear that painting is also a balancing of solids and voids, but also from the idea of wanting to clarify, as mentioned above, the eternal nature of painting, the capacity of art to be an indispensable force that moves the thoughts and actions of human beings.

In these polychrome works one will be able to see the fluid energy of water, someone will see in them curtains of confused smoke, still others will notice in them parts of the human body, landscapes, forests, plants, animals, the most diverse natural elements. With synaesthetic momentum one will almost come to smell the scent of flowers, the countryside, the sea. The sensations one gets from observing these paintings are different from those aroused by monochromes also because, unlike the latter, on the new works Faleni has chosen to intervene with opaque protectives, which eliminate all reflective effects and end up giving the painting the appearance of a captured instant, which, however, looks as if it could move again at any moment. And if the monochromes open up to more intimate, meditative, if not sacred dimensions, and suggest a sense of waiting and silence, the polychrome paintings, on the other hand, appear to be moving images (and offer the very sense of movement with the highest effectiveness), communicating the idea of a flowing stream, of life that is constantly changing and moving, of the many events that dot our daily lives. Transcendence and immanence. Spirit and matter. Concentration and distraction. The indefinable distance of color and the closeness of an encounter.

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis Maurizio Faleni,

Maurizio Faleni, Maurizio Faleni, Osmosis

Maurizio Faleni, OsmosisOn one aspect, however, one can be certain: the polychrome paintings are works that have a strong evocative appeal. When talking to me about these works of his, Maurizio Faleni quotes Otto Rank, the Austrian philosopher and psychoanalyst who was a follower of Freud before breaking away from the master and starting a completely independent path: in 1907, when he was only twenty-three years old, he wrote a book entitled Der Künstler (“The Artist”), to which he later returned twenty-five years later, publishing an expanded, revised and updated version that extended his reflections not only to the artist but also to art itself. It is interesting to note that Rank recognized in the earliest art forms, the prehistoric ones, the urgency to represent “an abstract idea of the soul.” this impetus toward abstraction, Rank wrote, “owes its origin to the belief in immortality, created the notion of the soul, and also created the art that served the same ends, and later led beyond pure abstraction, toward the objectification and concretization of the prevailing concept of the soul.” The primary purpose of art was thus, according to Rank, to give form to the invisible. In this “invisible” there is also the dimension of memory, of remembrance, of childhood reminiscences: this is where Faleni’s new research starts. The appearance of abstraction lives in the traces of reality. Speaking of his works, he calls himself a “drinker of images”: and the images he feeds on return in his art in the form of unions of colors, or “relatedness,” as he calls them.

What Maurizio Faleni does today in his studio, a few hundred meters from the sea in Livorno, is basically nothing more than what the Macchiaioli, the post-Macchiaioli, the frequenters of the Caffè Bardi, the animators of the Labronico Group did and have continued to do for decades in his own city. In short, the many generations of artists who breathed the salty, heavy air of this marvelous city, and who allowed themselves to be carried away by the clear, crystalline, full and dazzling light of a Livorno resplendent with glow, sunshine and life even in the dead of winter. That is, translating images into color by trying to find the form of light. The Macchiaioli, whom Faleni, as a native of Livorno, has studied and knows in depth (the best, for him, is Cristiano Banti, because he was able to intuit first the revolution of the Macchia), did so by resorting to the figure, while he, on the contrary, proceeds by abstract ways, but the soul is identical. Maurizio Faleni thus appears to be the repository of a tradition, an artist who continues to explore the paths of color beaten by his countrymen over the centuries, trying to open his own path, widening his gaze to the experiences of those who have investigated color, until he comes to exalt the charm and potential of color with original results, in an exceptional combination of techniques, knowledge, awareness, motivations, objectives, results. Getting to the light: a challenge at the limits of the possible. And precisely for this reason worthy of engagement.

Warning: the translation into English of the original Italian article was created using automatic tools. We undertake to review all articles, but we do not guarantee the total absence of inaccuracies in the translation due to the program. You can find the original by clicking on the ITA button. If you find any mistake,please contact us.